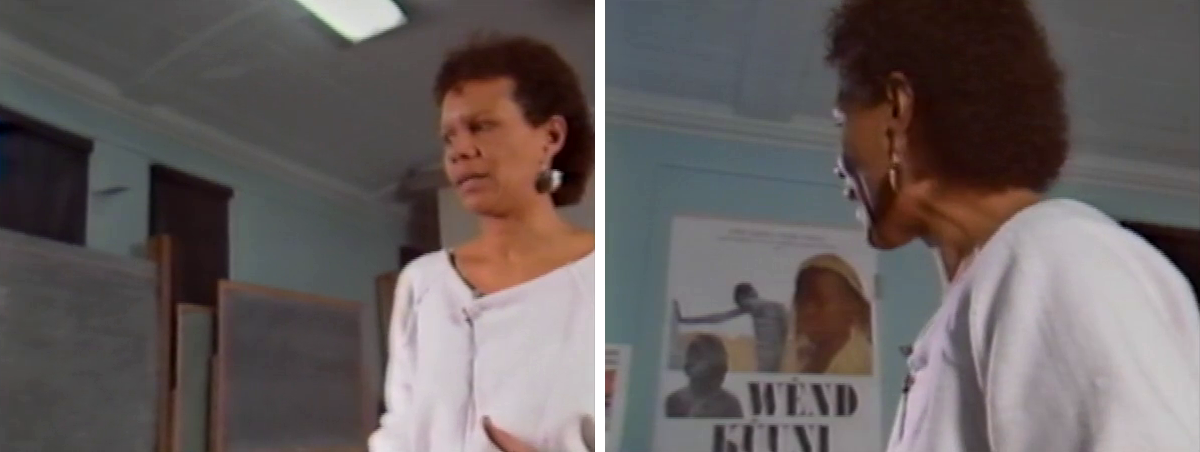

“I refuse to create mythological characters”

This text is an edit of the transcription of a master class given by Kathleen Collins in 1984 at Howard University.

In order to get at how I think about making a movie at a low budget, I have to be able to give you the theory, the narrative theory, that supports my reasons for making movies. If any of you have seen my work, you know I’m only interested in telling stories, and most of those stories are fairly contemporary. And to some degree they are ahistorical, meaning, though I think that is going to change, that the focus of the work is entirely narrative in orientation. I’d like to take about fifteen minutes and ask you to analyze with me something that I consider very important. There’s a book that came into my life when I was around twenty-four years old, and it’s called Saint Genet: Actor and Martyr. It’s a strange book because it’s about a French homosexual named Jean Genet, who I’m sure some of you have heard of. The man who wrote it is a man named Jean-Paul Sartre, a French philosopher who came out of the Second World War. And what he’s done in this book is analyze Genet’s place as a homosexual in French literature. Now, I suppose that would seem to you a far jump from talking about narrative structure, except in analyzing Genet as a homosexual, what he tries to get to is the nature of the outsider. Black people in America are classic outsiders. Sartre’s premise is that the nature of the Christian metaphysic is that one has to be saved. Therefore there are the saintly and there are the sinners. If this is a definition of reality, whether or not one is in fact an actual sinner, the culture requires one to have sinners. I hope I’m making that clear. Now, if you set up a metaphysic, a societal metaphysic that says that Christianity is based on the concept of salvation, that therefore there must be in life a moment of revelation in which one is transformed from a sinner into a saint. If this dichotomy or this split, which is what I want you to think of, if this split is made in the psyche, not only individually but collectively, you have to have in any society sinners and saints, because the Christian metaphysic has required it. It is an obligation. Now, obviously, if you take this context and you apply it – which Sartre does, not only to homosexuals, he applies it to Blacks, he applies it to women – what you come away with is the recognition that in American society we have been defined as the sinners. In other words, some particle of the society has to take the blame for the sins of that society, the evil impulses of that society. Because you’re working out of a dichotomy now. You’re not working out of a Buddhist tradition in which oneness is declared potentially possible for every human being. You’re working out of a Christian metaphysic that says one is first one thing, and by an act of transformation one becomes something else. It’s the essential split in the psyche. Positing that split in the psyche, transfer it to the society and what you get is projected sinfulness on somebody. Now we were the most convenient scapegoats. It’s a game, or it’s a projection, that has gone on now for several centuries. It is important to understand not only one’s position in the society but the emotional role that you play in the society. And the role is more important than the position, because the role defines not only your behavior but the necessity of the insider to have you there as an outsider so that the notion of sin can be projected outside of him and onto somebody else. It’s a very, very important concept. Because in this culture, what has happened is we have been defined as the outsider. Instead of experiencing sin as an inner dynamic, what a white person does psychologically, and literally in a collective way, is he imposes his notion of evil onto us. It is why we experience intense discomfort – for example, when we walk into any social situation with white people, there is an immediate discomfort that we experience. It is physical in its intensity, and it comes out of the knowledge that we are the projection that whatever they could not handle in their psyche has been projected onto us. Therefore, in some ways we experience ourselves in a public format like a collective garbage pail. It’s an ugly way to do it, but I insist on the ugliness because I do not know of one black person, in my experience, who has not had psychically first to deal with their own feelings of ugliness. And the feeling of ugliness comes out of what has been projected onto us, as the sinner, as a person in whom evil resides, as the split. The division has been made – it was very conveniently made. Slavery made it a very convenient formula. But the nature of the formula as it is passed down is that since the basic Christian metaphysic, while it is in what they call the Aquarian age being argued against by the notion of Buddhism and the notion of Eastern religion that is opposing a sense of division and saying that unity is fundamental to every human being, that the division in fact only exists in any single soul, and that that resolution happens internally, that it is not an external dynamic. That consciousness may be slowly creeping into our reality. But the point is, we are the outsider.

Now, If you’re an outsider, and this is where I begin to verge this into narrative – you can’t understand why I do the work I do unless you understand this, because this is the basis of all the work – if you are the outsider, if you are the sinner, you are by definition extraordinary, meaning you are either super good or you are super evil. You are super sexual, or you are super ascetic. You cannot arrive at normality because that is the one thing that has been denied you. If you look very carefully at the history of black literature, to a large extent, up to and including writers like Alice Walker and Toni Morrison, if you look at the history of black literature, with few exceptions, it is the history of creating mythological or mythical black people. Hagar in Song of Solomon (Toni Morrison, 1977) is a woman without a belly, without a navel. Why? Because she is meant to contain wisdom, or a certain kind of psychic spiritual power that is extraordinary. This notion of the extraordinary forces us narratively, when we begin to do our own stories, to write about ourselves, it requires, or it imposes, because we’re the outsider, because this has so deeply infected some part of the psyche, that it almost like it’s if you look at your spine, one part of your spine is normal and the other part of your spine is this huge person that is bigger than life. Not bigger than life necessarily in a positive way, but bigger, must be more evil, more sexual, more, more, more. The word larger applies, not the word normal.

Now in your personal relationships, I posit that this creates a kind of self-consciousness in the individual. It creates a self-consciousness in which our experience of normal emotions – love death, marriage, birth – are to some degree distorted. And while we go through the same human experiences that everyone has gone through in any culture, generation after generation, they happen to us in a slight void. For example, the cliche is that someone like me was raised watching Greta Garbo fall in love, Elizabeth Taylor fall in love. It’s not only that my beauty was rejected – that’s ultimately shallow. What is important is that my ability to participate in the emotion of love was fundamentally distorted because I was not Elizabeth Taylor. Therefore, if I had any notion of love, I had to imitate someone’s idea of it. It was not my idea. I was not an insider. Therefore, anyone I loved, I did so to some degree self-consciously, meaning the outsider dared love. It is no accident that white people do not enjoy seeing ordinary black people’s lives. It is no accident that in most of the TV series the black characters are still, and this is the insistence, are still caricatures. There is no, no, no difference whatsoever between Hattie McDaniels fifty years ago and that woman who plays the maid in whatever the hell that bloody thing is that she’s in. The point is the notion of ordinary existence is denied.

I’ll give you a very good example. When Losing Ground was first shown in a theater for distributors… As you know, it’s just basically about a husband and wife. The husband is an artist and the wife is a philosophy teacher. Basically what happens is you see them go through a trauma in their marriage and you see them try and resolve it. It’s really not any more complicated than that. When white distributors saw that movie, they came up to me – not me, they didn’t dare come up to me, but they came up to the people who were working for us and trying to get us distribution – they said, “we don’t know any black people like that. We don’t know any black women like that. This is amazing because where’s the racial angle here?” I posit that that movie has so many racial angles. The premise of the movie – and I take this back to this experience of love – is that no one ultimately is going to mythologize my life. No one is going to refuse me the right to explore my experiences of life as normal experiences (neither outside nor inside), as human experiences, and that the humanism of that experience is, I posit, the last hurdle we have to transcend. Now, when it comes to character development then, which is really what we come down to, when it comes down to actually telling stories, what I really want to present to you is: How do we divest ourselves of the need to make ourselves extraordinary? Now, the danger – and I think it’s a danger that maybe we’re just beginning to come to grips with – is that we must now be too good. You see if you’ve been too evil, if you’ve been the notion of sin incarnated, and you’re now trying to correct that balance, what do you do? You make black people into saints. You go from being a sinner to being a saint. Neither one is true. Neither one has anything to do with reality. Both are traps to dehumanize you. Both refused to accept the fact that you live, breathe, and die out of an internal psyche, which is extremely private, extremely idiosyncratic, and neither saint nor sinner.

Therefore, when you begin to think about narrative, the problem for us is the process of demythologizing ourselves. Otherwise, there can be no truth apprehended. Now that’s very theoretical. On a practical level, which is down to where you write scripts, where I write scripts, if you can hold that as the subtext, which is my subtext, I write out of that subtext. I refuse to create mythological characters. That is my obsession. That is my artistic stance. That is where I will, as they say, rise or fall. I am not interested in mythology. I am interested in ideas. I am interested in how human beings evolve a consciousness, which is true to who they are in the center of their being. I am interested in telling stories that give pleasure to the psyche. Pleasure is a very important word. And in doing so, I have to take you through what I call the real and the symbolic, because I’d like to leave you with some very good structural things for you to make, to use. You want to tell a story. Would someone like to give me a character they’re working on? Because what I’d like to do is to show you how you translate this idea into how you write a script.

Michael Stewart is someone who has grown up in Youngstown, Ohio, and has lived with his parents, well his grandmother, all of his life. His parents were divorced at an early age. His grandmother had sheltered him, walked him to school from the time he was six until he was eleven. He goes away to college. He now does not know how to deal with the normal situation or what’s happening on a college campus. He still remains in a childhood atmosphere.

Now, what do you like about this character? Why do you want to tell his story?

I want to tell his story because he represents everything that should be, he thinks that the world should be good.

Can I stop you one second? What’s the word that stands out in what he just said? “Represents.” He represents, in other words, this character’s relationship to you is representational or symbolic. You hear what I’m saying? Why do you like him? You see what I’m saying? What I’m asking you is, why does he intrigue you? Does he intrigue you simply because he represents an idea? The two words you should have down on your paper if you’re academics are “real” and “symbolic.” Now there is a symbolic level to every character. There’s no question. But the question is the order in which these two things get hooked up. The real, as far as I’m concerned, better be the conscious motivation, and the symbolic better be the unconscious one.

Now, let me explain that again. If you had said to me, the thing about Michael Stewart is he really reminds me of myself. He’s scared, and he can’t adjust. And, you know, he sits in his room and he’s scared to go to class. Now, what am I doing with this guy? First of all, I’m creating an environment for him. You’ve given me this character. If you told me as a writer “now make something of Michael Stewart,” I have to figure out an environment for Michael Stewart. First thing I would do is if he’s on a college campus, right? I would say this guy lives in a single, he’s a pampered kid. He wouldn’t want anybody else around him. His room would become his haven. I am transforming this character into a fictional character. I am going to do that out of my impulses, out of my feelings. I am not going to do it out of what I want somebody else to think about him. I don’t give a damn what anybody else thinks about him, because I can’t get to the truth of him unless I can figure him out for myself. Now, what I want you to do eventually is to apply this to history. You should be doing the same thing with any black historical character you like. He is not a priori good, bad, saintly, sinner. He is not anything. He is somebody who, for some reason attracts your psyche. Why? Because there is something in either his obsession or his habits that rings a bell in you.

Michael Stewart. First thing I would do would be to give him this, this environment, which is very, very important when you create film characters. Then I would figure out one other person to whom he is able to relate in any way, honestly, on this campus, in this situation. So that I begin to structure his habits. The room would be very important to me. I would probably spend time, on the first draft of the script, getting everything in that room straight, what he puts in the room, where he sleeps, is he someone who dreams a lot? And I would be doing this by having him go through me. You see, until the reality of him began to live in me. Then I would know every single thing this guy does. I would know whether he got good grades. I would know if he stopped getting good grades, why. I would know how he ate. You know, certain kinds of people who are very repressed in a way, which is really the kind of guy you’re getting at. He’s a guy who was sort of repressed at a certain state. He’s stuck, he’s stuck somewhere. And it’s his stuckness that the audience has to feel. How is he stuck? Does he stop eating for example? Or does he overeat? Both of which are possible, but I can’t answer that until I get into his head real good, you know? How does he study? Is he one of these people who is so meticulous? He’s got all his books out here, and he’s got to have five pencils sharpened, you know, and he takes very meticulous notes on everything. And what happens if he fails an exam? Does he cry? He might because he’s still trying to please somebody, but the food of the character would have to come from me having something about the character that really obsessed me.

Any other kind of character places you in what I call the mythological realm. What it does is you say, well, I’m going to do this character because he was very important in black history, or I’m going to do this character because after all he reflects the values of our people that we are trying to present to the outside world. And in presenting this character, I am therefore moving the black race along to a greater sense of perception and self and so on and so forth. That is the rhetoric. That is a lie. That does not work. And it doesn’t work because the impulse in any human is to reach out towards somebody else’s humanity that makes sense to them. That is where change happens in the psyche. It does not happen out of an external respect for ideas. It happens out of an internal longing for feeling from the inside of a character. That is where change happens. The characters, the books you have read, go back over everything that has mattered to you. It is when some little bell got rung between what you read and what was going on in your life. It is no accident that we can read certain books at certain ages of our lives and never read them again. When I was nineteen, I read The Brothers Karamazov (Fyodor Dostoevsky, 1880). When I was thirty-five I read it again, and it meant nothing to me. But at nineteen it meant everything to me, because I was obsessed with good and evil and all kinds of notions of value. And I wanted to understand why certain people were oppressed. And it was the beginning of the sit-in movement, which is part of my formation, but not necessarily part of yours. And I wanted to understand why we were outsiders. And there were ideas in that book that spoke to what I was concerned with. They were not external to me. Some very learned scholar could explain that behavior on an academic or mythological level. It does not mean I would connect with it. So what I am saying to you is when you have a character, when you begin to say, I am going to do a film about thus and so, the most important question to pose, and it really shouldn’t be posed as a question, It should be experienced as a kind of drawing, a kind of attraction, which is partially conscious and partially unconscious.

People say: “You write a lot out of your life. They say Sarah Rogers is that Kathy Collins.” She isn’t Kathy Collins, but she feeds off of my obsessions, my concerns, my feelings, if I can make that distinction. She is larger, different than me, but I know her, and I know her because I’ve let her sit in me and marinate with all my obsessions. You see what I’m saying? Until when I got her down on the page, there were very good reasons why I wanted her to be a teacher. There was a kind of rigidity to her body, and to her posture that the academic environment would totally satisfy. You would get her right away, you would get a woman who has disciplined her mind and her intelligence into a very narrow channel. The fact that she isn’t an environment that is academic is an entire reflection of that narrowness. You cannot sit in the classroom without feeling to some degree you are in a straightjacket. You’re in a straightjacket now. You are required to some degree to pull all your energy into focusing on what I am supposedly saying to you that you hope makes sense. But the point is that you are channeled by the environment, particularly an academic environment. And I wanted her to be channeled in that way. I wanted you to experience the psychological rigidity by creating an environment in which people feel that rigidity in their ordinary lives, people feel constrained in a classroom. It’s both a physical constraint and a mental constraint. Your mind is not free to roam. Somebody may have broken up with their boyfriend last night. For some reason, in this bloody environment, they’re supposed to listen to me when in fact all they’re worrying about is whether he’s going to call at four o’clock this afternoon. But there is a constraint that has been imposed on you. You are therefore forced into a kind of mold.

That kind of sense of the environment is very important. When I was a young writer – and I don’t think of myself as a young writer anymore, and I’m little bit proud of that because I feel that maybe over twenty years I’ve understood what the craft of writing is – when I was a young writer, however, I did do one thing that made sense, which is I always started with where people lived, what their little habits were. First script I ever wrote is a script called Women, Sisters, and Friends. I was very young. I had never written really anything. I’d written a lot of journal notes and maybe a couple of little short stories, but I wanted to write a film script. I’m reminded of this experience because I was in LA this last weekend, and I went around to raise money for this movie for years, and they said, “Oh, there’s no such thing as a black, as a black director. I mean, you’re crazy. Forget it.” And I did forget it. And that’s why I wrote plays for a long time, and stories, because I thought it really wasn’t possible at that time. It literally was not possible. What you all are experiencing now was unheard of in a way not so far back, I’m talking 1965, ’66, ’67. I’m almost talking twenty years. The point is, I had this idea, I saw these three women on a beach. That was all I saw. And from that one picture, which was the one thing I knew was true that I wanted to talk about women and women’s feelings, and I liked them being on the beach. And then I gave them this house. This is what I did before I wrote the script. I gave them this house and the house set right on the water. And I took elaborate time describing this house and the rooms in his house. And there was a piano in one room. And when I got the piano in one room, I said, “Oh, then I can make one of the characters a musician.” So I made one of the women a pianist. And then I literally walked out of the house down to the beach. And when I got down to the beach, I saw that there were all these glass fragments. Now this is my letting this just come out of my consciousness. I saw all these glass fragments. One of the women was obsessed with pasting glass, making little glass collages. Now don’t ask me where that came from. Except in A Summer Diary – this is a script I’m getting ready to do – twenty years later, that glass image is now transformed into a woman who was a set designer. And the set that she builds for this movie is all made out of glass. And now the image and the idea begin to make sense, because I really see that the woman felt her life was very, very fragmented, and she couldn’t put the pieces together. And what she was doing with this glass was really trying to make sense, a kind of mosaic of her life. The third character came out of, she looked out the window. I saw her looking out the window one day and there was this man walking up and down the balcony singing “Oh fix me, oh fix me, Jesus, fix me.” It’s an old, it’s a very old Southern spiritual. I don’t know why he was singing that. But out of those mental images, I constructed this whole script about three women who come to a Caribbean island to spend a vacation. And they are obsessed with this mysterious man who walks up and down the beach in white pants singing “Oh fix me.” It’s a wonderful script. I’m sorry that I outgrew it before I could do it. But the best ideas in that script, and I was just reminded this because one of the actresses that I wanted to do it with years ago, I saw this week and I hadn’t seen her in many, many years and she can, she remembers every detail of the script. And she now sees how much of that script I have finally incorporated into the next movie I want to do. The point is that allowing yourself to feel an environment, because if you think about film in the bare sense, it is nothing, and I insist that it is nothing but space and light. That’s all it is. It is the placement of people inside these two illusions, which are space in light. Therefore, the first thing you should do when you think about film is you have to think about the freedom to move people through space and light in ways that make a statement about who they are out of the raw material of film. Not first out of language, language is to some degree, it’s not that it’s secondary, but that it has to come out of a respect for the geography of cinema, which is these two dynamics, so that language shouldn’t be the starting tool for developing film characters. The language had finally just happened. What they say, if the environment is correct, what they say, if the camera angle is correct, flows naturally. Now I teach screenplay writing and I argue that – I argue it because a lot of people write screenplays and they don’t put in camera angles, camera directions, even Haile Gerima argues with me about this because he says, “Why do I have to have every camera direction in right away?” I have to do it only because when I know, or when I have a sense of, how that person is going to be looked at, I know what they should say. Now, even if it’s changed later on, at least if in the initial concept I have architected them, which is really the word, in space I know what this supposed to say, because I know what’s in the room. I know where the window is. I know where the door is. I know if there’s a refrigerator they can open. I know if they’ve got plates in front of them, I know where the other person is going to come in. And then I know what they would say to each other, because I have located them in a way that has given me a complete grip on them.

I don’t know how to sum this up, except that if we go back to that subtext, and we decide in our consciousness that we refuse to be mythological… This is how I’ll sum it up: I don’t want this to be construed as ahistorical. It is not at all. The next project I’m about to do is in fact about a woman who was the first black woman aviator. She flew in 1917. I mean, she’s just, you know, incredible. Nobody’s heard of her. I mean, it’s mind mind-bending. However, it is not the heroics of her as the first. You see what I’m saying? Because when she’s a first, she’s a saint for God’s sake. What I’m interested in is why the hell this woman would want to fly. I just asked Abby, who I just found out flies, if he would take me up in airplane. I have no idea why somebody would want to leave the ground and go hovering around up there and flying around. Why would they want to do that? Yet there is something about this woman that is really calling to me. I can’t get her out of my head. But to get to her I have to do a lot of stuff. There is a lot of history I have to know. There is a lot of soaking in the history I have to know. But what I really have to know is why she wanted to fly. What was it about flying that mattered so much to her that she left the country, went to Europe, and, with great trouble, got a pilot’s license? Now you see, this is where the myth and the truth separate. You could make a great documentary about the fact that she was black and flew, that she went through all of this travail and hardship in order to fly. Personally, I really don’t care about that, except if I can add to that a total penetration of her psyche, because if I can do that then I can make her entirely human because whatever the hell was motivating her came out of her obsession, came out of her need, it came out of something in the middle of her that needed expression. If I can get to that, then I can reconstruct a woman, not a myth.

I was very touched by the way you create your characters. I wanted to know: When you create a character, does it come from the fascination of a certain person that you’re interested in? And also if you were interested in this person, do you go up and talk to this person? What if they don’t tell you how they feel, and how do you create a character from that?

I wouldn’t say it comes from an obsession with the person. I would say that it comes from trying to understand something that happened to me. For example, if you’re asking me where I am autobiographically in Losing Ground, it is not in any of the characters but in the idea of change and infidelity. What does unfaithfulness mean? And what does it mean to want to change? What happens when you’re going through changes in relationship to the people around you? What do you have to do? Is it, does it have to be violent? I was really reflecting on my own marriage, but many years later and trying to understand experiences that meant so much to me that I was obsessed with them. In other words, what happens if you face the things you can’t get over? The most interesting characters by the way are obsessed. Or the writer is obsessed. I mean, there are people, for example, who fall in love, right? And when the relationship is over, one person goes on to other relationships and makes a happy transition and resolution, and the other person remains stuck. They can’t get over this person. You know, it happens all the time in life. Well, why? And if you could probe that feeling or that experience, or that inability to go beyond something, it’s that that is the grip, the gripping thing.

I’ll give you a very recent example. The American Place Theatre, which has done some of my plays, called me in a couple of weeks ago and commissioned me to do a play. Now, the only context I have to give you, because it is an important context, is they brought me in, and I’m the only black playwright they brought in. And they brought in seven white women playwrights. Now the American Place Theatre is sort of famous now for kind of modern avant-garde, you know, women’s work, feminism and all this crap. Now I’m in the room with these women, and I’m always an outsider when I’m down there. Okay, they like me, they think I’m talented, so on and so forth. Okay, but there’s a dividing line. They wouldn’t kill themselves to do my work. They would do my work if they’ve got to have one black play in a season, right? That’s the reality of it. Their ability to assess me is entirely dependent on the packaging, you see, because I’m a packaged person to them. I mean, that’s just a fact. I know that, and I have to juggle wanting my plays done. I have to juggle all the other things, because I know that I come to them as the black writer in the project. So what they’re expecting me to do, and what they want to do is a series of one act plays on what they define as difficult women. So, you know, I suppose they want me to take Harriet Tubman or somebody and, you know, I mean, I’m sure that that’s what they want to do. What I’ve decided to do – and the reason I’m telling you this story is it points to how I always work – is I’m very tired of not quite understanding, or not having brought out in the open, the peculiar outsider-insider relationship we have. It is so dishonest that it is really painful for me to go down there and sit because I know I’m never seen. They look at me, and they look through me. They look at me, and they look around me, and I want to talk about that. So I didn’t even agree to accept the commission. I went home, I thought about it for three or four days, and I finally came up with this idea. And what it is is a middle-aged white woman and a middle-aged black woman are sitting in a waiting room, waiting for a psychic. [Laughter] Why!? Because I can do a play about what it is between white women and black women that is so destructive, so psychologically twisted and mixed up. I want to understand it cause it, it doesn’t go away. It’s all the time. It’s one of the things I have to face. So what my problem was the exact thing I was talking about. How do I find an environment, a situation, in which what upsets me can begin to make artistic sense? So I thought, and the first image I got was… I knew I wanted to have a white woman and I knew I wanted to have a black woman. And then I knew, I knew that I got a visual image, and I want the black woman to be a fashion designer. I wanted her to be a splashy dresser and everything. And I want the white woman to be a writer. And I can explain to you in a sense why, but I really couldn’t until I finish the play because I’ve just sketched it out. Then I said, well, now they could be waiting, who could they be waiting for? And I said, they’re both waiting to see this psychic. Why? Because somehow I know that that mix is going to get to everything I want to get to. In other words, once I get the scene set up, I’ve got the place, I’ve got the characters, I’ve got the environment, I’ve got everything I need – now I gotta write it. But what I want to write about is basically: Where is the humanity lost? I want to get all that feeling connected to that out of me once and for all. And it’s the only piece of work I will give them. I wouldn’t give them anything else because I cannot continue to define myself in that situation unless I have clarified my inner connection to it. I hope that makes sense because it is working out of something that some situations, some experience, some idea, some feeling that has real, has real pain and disconnection connected to it.

Do you experience any difficulty to not to compromise your beliefs?

No, nobody is that interested in me. It’s not so difficult for black people in a certain way, because nobody in a certain way is really that interested. You are freer than you think. You’re freer than you think because the screen that is around you is so thick that, behind it, you can do an awful lot of thinking, an awful lot of figuring out. It’ll take a long time for the world to even catch up with where your ideas are because you’re not being perceived as a thinking being. So you’re freer, you’re a lot freer than you think.

I want to ask you: How free are you as a writer to portray the ugly things that we as black people feel because of this dichotomy. Like Alice Walker really gets into it. I mean, I’m reading some of her characters, like in The Third Life of Grange Copeland (Alice Walker, 1970), the son, I mean, you know, he just drags the woman down, but some of them, even though we know it’s exaggerated, some of this stuff is true. There are some true aspects about how we denigrate each other and put each other down. How do you feel about it? I mean, do you feel that should come out of your work since it’s reality that black people do feel this way? Or do you want to, you know, push it to the side?

No, I wouldn’t. I don’t want to push anything to the side. On the other hand, I don’t want to romanticize it either. In other words, it’s possible to romanticize evil, or it’s possible to do the same kind of romanticization of negativity as it is of positivity. The danger is: Are you interested in what you’re saying about those people, or are you simply presenting it because you feel it should be presented? It’s all question of intent. The other thing that I think you have to be careful of is, you should never write about anything that you yourself really don’t feel experientially. Don’t get a feel for experientially. You should never try and write about characters because you think they represent something in the black experience that should be said. I think that’s a very bad trap, because I think what happens from the beginning is you develop an audience in your head of white people to whom you are going to explain the black condition. It’s the wrong audience. It’s the wrong audience entirely. The pleasure of writing is imagining people laughing or being amused at your work, while the people that laugh and for the most part are going to be amused at my work are the black people, because they’re the internal audience that I see when I write. So when I write and I do something funny, I get very excited at the idea that they might laugh at it. You see what I’m saying? Because the only audience I have is my family. It’s my past, but it’s the, it’s the sort of subconscious audience that really raised me and, and the, and the milieu around which all my early memories come from. Those the people you write to, and if you’re writing to somebody to explain something, you’re off on the wrong track. You’re never going to say anything that really touches people. You just can’t.

How long before we will have real human black characters that we do relate to, that we accept more readily than what we see on TV.

It’s definitely already started. I mean, there’s a body of independent work now that is just, you know, there’s no, no question about that. That’s the direction it’s going. And the problem is, is we have to get those images in the commercial arena to the degree that people can see them and say, “Oh, this is all right to talk about. It’s all right for me to have memories about my individual past.” The problem is that the films that are being done in this area, we’re all stuck in this kind of small-circuit audience problems so that, so that most black people don’t even know about our work, they don’t get a chance to see it. We screened Losing Ground in an old-folks home in Harlem. And there were maybe twenty people over eighty years of age. And there were a couple of drunks that came in from the street, and boy they had such a good time. They understood, they talked to the characters on the screen. There was this, there was this old guy who was totally drunk. And you know when the husband gets real nasty to the wife, he said, “you shouldn’t talk to her like that!” And he was going on and on, you know, he understood and said, “you’ve got an intelligent wife, and she’s trying to be good to you.” People have accused me. They say, your work is very intellectual. He had no problem with Sarah at all. Sarah was up there talking about Sartre and everything in the beginning of the movie, and this guy was going “Now, this sister can talk.” He did not care that she was saying stuff that he necessarily couldn’t understand. He got who she was. He said, “Now she can talk.” He got the interrelation of everything. He had no problem. And in the end, when there’s a scene where Bill kisses the Puerto Rican, where Victor kisses the Puerto Rican girl, he said, “Oh no, man, you know, this is going to be a bad mistake.” They were so happy, you know, they just really enjoyed it. And it’s experiences like that, that make you aware that if the movie could just be seen more and more than you would just recognize that there is a hunger just to see black people going through life experiences, being sometimes good, sometimes bad, that, that doesn’t matter. It’s got nothing to do with anything. Behavior is a wholeness. It doesn’t have compartments.

You’ve been talking about how the humanity in someone else makes you react and that’s what you reach out for. As you know, when I came to Howard University, I don’t think I was really thinking. And every teacher I’ve had this think, think, think, and that’s what sticks with me. Because as a TV generation, you just react to feedback. You react, you cry. Oh, that was sad. So you cry. And like, when I watched E.T. (Steven Spielberg, 1982) I was just pouring tears, I couldn’t see it again because I was reacting so much. But because I hadn’t been trained to think, I didn’t know what I was crying about, I really want to know how I can get to that part of me when I can sit down and say, what is making me react this way and understand, disciplining myself to understand.

it’s a very important question you raised because have any of you seen Terms of Endearment (James L. Brooks, 1983)? Yeah. Y’all sat there and cried too. Right? You cried. All right. Okay. I cried a little too, but I was so mad at myself. I was ready to kill myself. [Laughter] But when I was talking about that business about love and Elizabeth Taylor, right? One of the things you have to get to is, is that, you know, there is a small part of your psyche that has been, distorted is a not a good word because it doesn’t get to the emotional thing. It’s, been made to feel like those dreams are real, you know, that, in real life people love each other and never leave each other. And, you know, If they die, then it has to be sort of dragged out. I mean, you can’t just die and be happy for somebody or die and be free. You, the nature of being an, uh, being an outsider is that there is always some little part of you that yearns to be inside. And the problem with movies and E.T. and all, no matter what you say is that in some part of you, they’re inside and you’re still outside, and you’re crying a little bit cause you would like not to have been outside because being outside is never… the pain of it never goes away. That’s the thing you have to really face. And since the pain of it never goes away, there will be always these little moments when… the reason why I want to do this play about the American Places, really, because there is a part of you that suffers in a way that never goes away. It is a terrible thing to be made to feel that everything that happens in your life isn’t quite human. That is a terrible thing to live with. And the horror of it, I think it hits you sometimes when you see these really cheap melodramatic movies, because a part of you in the larger sense senses that they’re still inside, whatever inside is, and you are still outside. And I think that’s really where there’s a kind of pain, and it isn’t necessarily that you’re crying because you either liked or believe those characters. But if you remember as a child the yearning to have experiences like anybody else… Now, who was anybody else? Anybody else was unfortunately, Elizabeth Taylor. The yearning to have those experiences, and then the symbolic identification, they work against you and they create something that you’ll never get over.

What differences do you perceive between third-world films and Western films, in the industry and in the content?

I would say that the real difference is that in the good independent films, like Haile Gerima’s or Charles Burnett’s work, what happens is that there is a real effort to marry drama and idea. The filmmaker is the one who has obsessions of his or her own that he or she is probing. And these ideas control the style rather than in commercial cinema, where idea is absent and content and style are simply a packaged formula. In other words, there is no growth because there is no idea generating the relationship to the image. Now I’m talking about Haile’s and Charles’s work, mainly because, as you know, I’m highly narrative oriented. I mean, I have a great interest in narrative film, and particularly in experimental narrative film, in which the ideas that are trying to be communicated sway, dictate, and influence the style so that the style becomes quite inventive. A very good example is in Ashes and Amber (Haile Gerima, 1982) – the scene that is always riveting to me when the grandmother is serving food to her grandson. It’s very elliptically cut. And what it does, it’s because it’s the notion of nurturing, I mean, I don’t want to speak for Haile, but I would say that it was the notion of nurturing and the grandmother as nurturer that he was after communicating. And what happens in the elliptical style is that that elliptical style makes you remember all the memories of nurturing that you might’ve had from a grandmother, from your mother. It makes meals into a ritual. And it’s the memory of the ritual that you begin to experience rather than a specific grandmother feeding her grandson and nurturing her grandson. No, the style has imposed upon you a memory trace. And while you’re sitting there, you are remembering all the moments in which meals meant coming home and in which meals meant nurturing. But it is because he was after that idea, and the idea dictated developing a style that would communicate that idea. Now the simple Hollywood film, all they’d probably want is “Hey guys, let’s do the scene at the dinner table. It’s an easy place to do it…” There is no idea content. So you’re going to shoot it probably in a very standard way. In Terms of Endearment, one of the most banal scenes in the movies is that supposed to be funny dinner scene with Shirley McClain and her three men. Well you never find out who the men are, you never find out what she’s interested in, in any of them, because there is no idea content. Otherwise the scene wouldn’t have been shot master, medium, close-up. It might’ve been shot circling the table. You know what I’m saying? It might’ve been shot from that little fat short guy all the time looking up at her. I can’t tell because the script has absolutely no idea content anywhere in it. But what I’m trying to say is, is that it’s another example of an absence of idea and therefore form suffers. And that’s what I would say is different. Killer of Sheep (Charles Burnett, 1978) is a highly stylized film in which the pacing is very critical to your recognizing the despair of the main character. And really all that happens in that movie is that the main character moves out of despair into hope – fragile, a fragile transition. It is not dramatic in the Hollywood sense. I mean, Terms of Endearment, what do they do to get drama? They have that young woman die – her death is about as phony as a $2 bill. You never anywhere actually believe that in her character she would lead to… it doesn’t make any sense. I mean, I said “Huh, now she’s got to die of cancer, why did they do that for?” I didn’t understand it. And I didn’t understand it cause it didn’t come out of any context. A simple emotion can be a movement out of despair into hope, which is the whole architecture of Killer of Sheep. That’s really all that happens. The really critical scene to me of continuity is the scene when he gets that motor and they take forever to get the darn thing up on the truck. And it takes so long, and when they get it up on the truck, what does it do? It rolls off. It’s just a perfect, perfect expression of struggle of despair and of acceptance, that one can go so far and then still the whole thing can collapse, but then one can rise above that. It’s a visual metaphor. What it meant is that the filmmaker knew what he wanted to talk about. That metaphor is no more an accident than God, as far as I’m concerned. It is so well thought of as to me of almost the symbol of his despair, you try and you try and you try. And in some ways, as black people, you really end up still falling off, and yet where then where then does your hope come from? It still must come from within. It still must come from a final decision to live in spite of the odds that are against you.

With thanks to Nina Lorez Collins and Milestone Films for making the video recording of this masterclass available.

This text was published on the occasion of ‘Milestones: Losing Ground’, a collaboration between Courtisane and Sabzian. On the occasion of the online screening, several texts have been published on Sabzian, selected and edited by Stoffel Debuysere and Gerard-Jan Claes. ‘Milestones: Losing Ground’ takes place on Thursday 3 June 2021 at 19:30 on Sabzian. You can find more information on the event here.