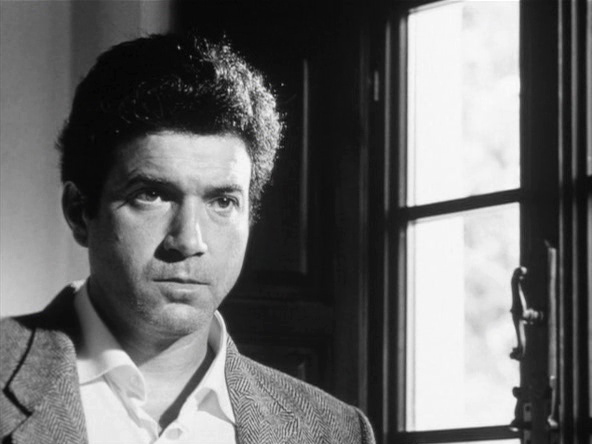

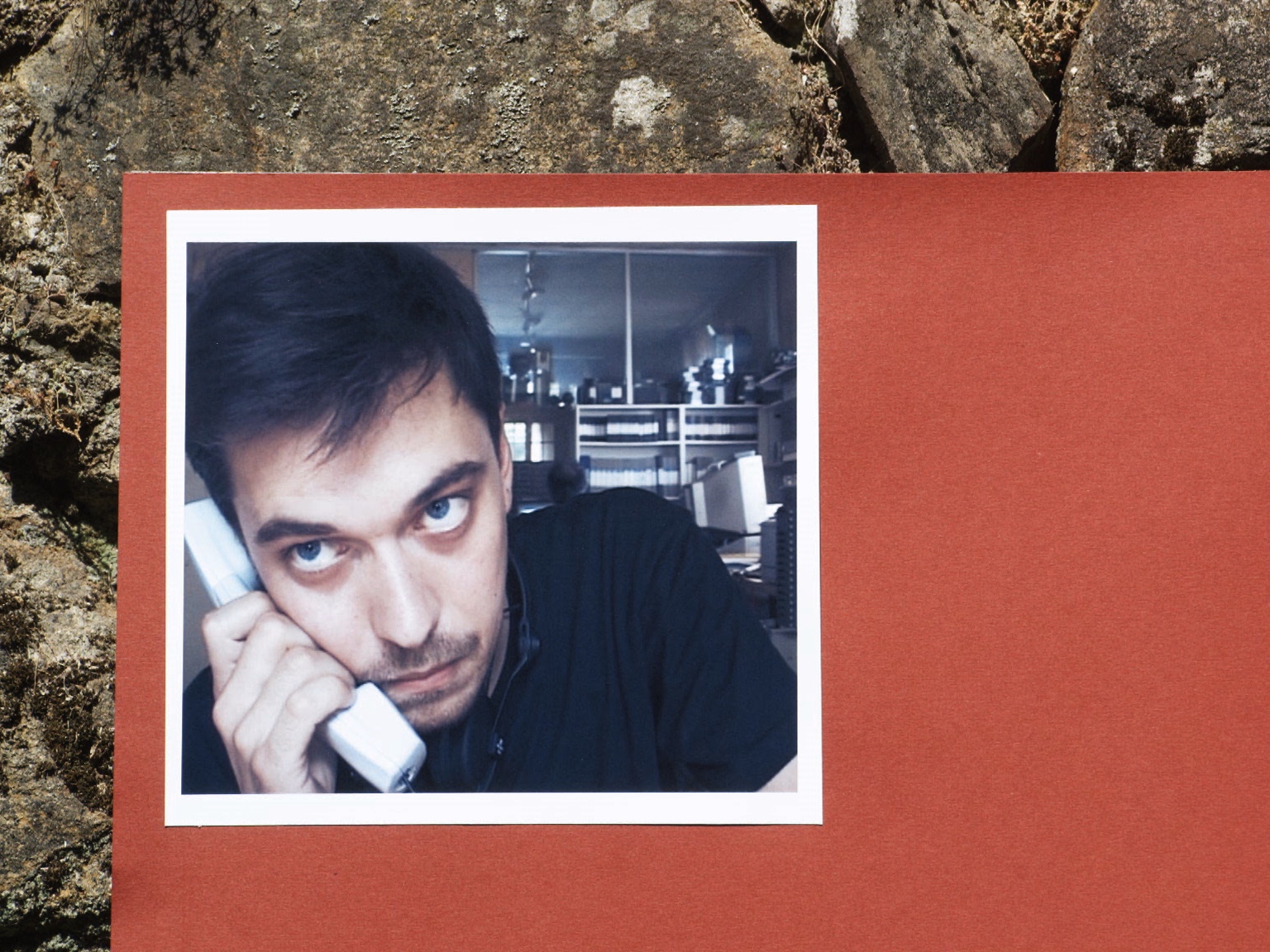

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub

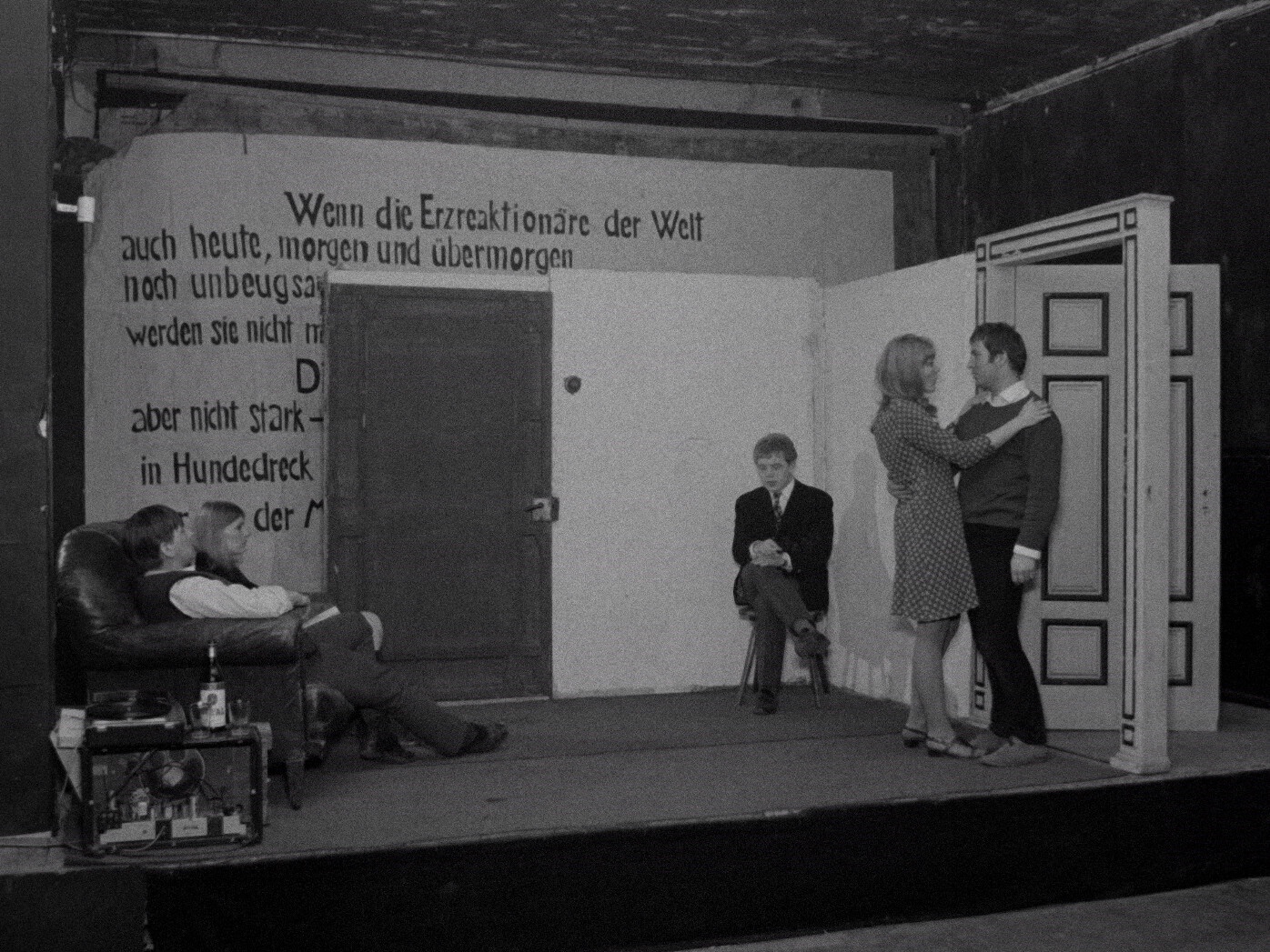

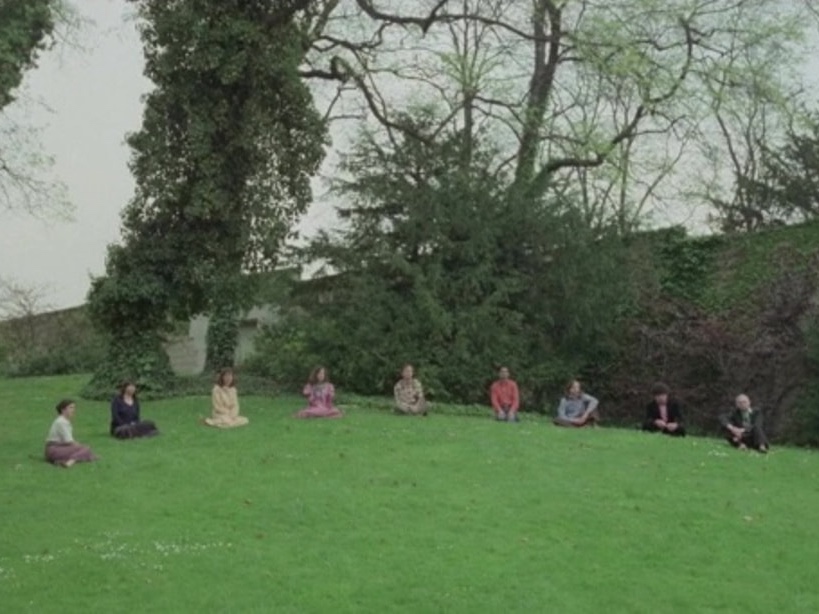

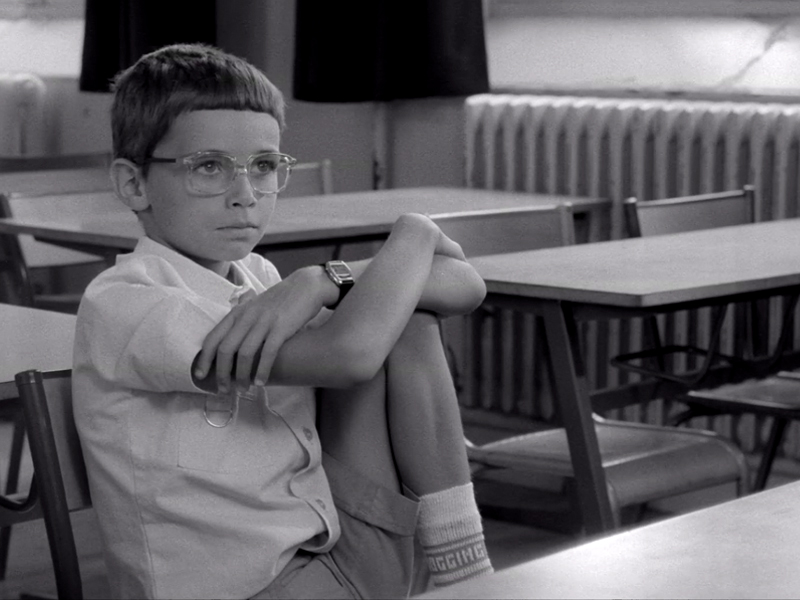

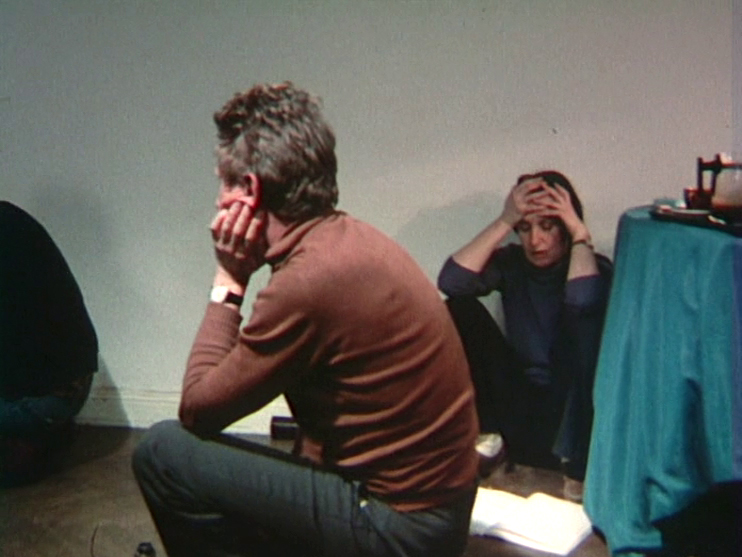

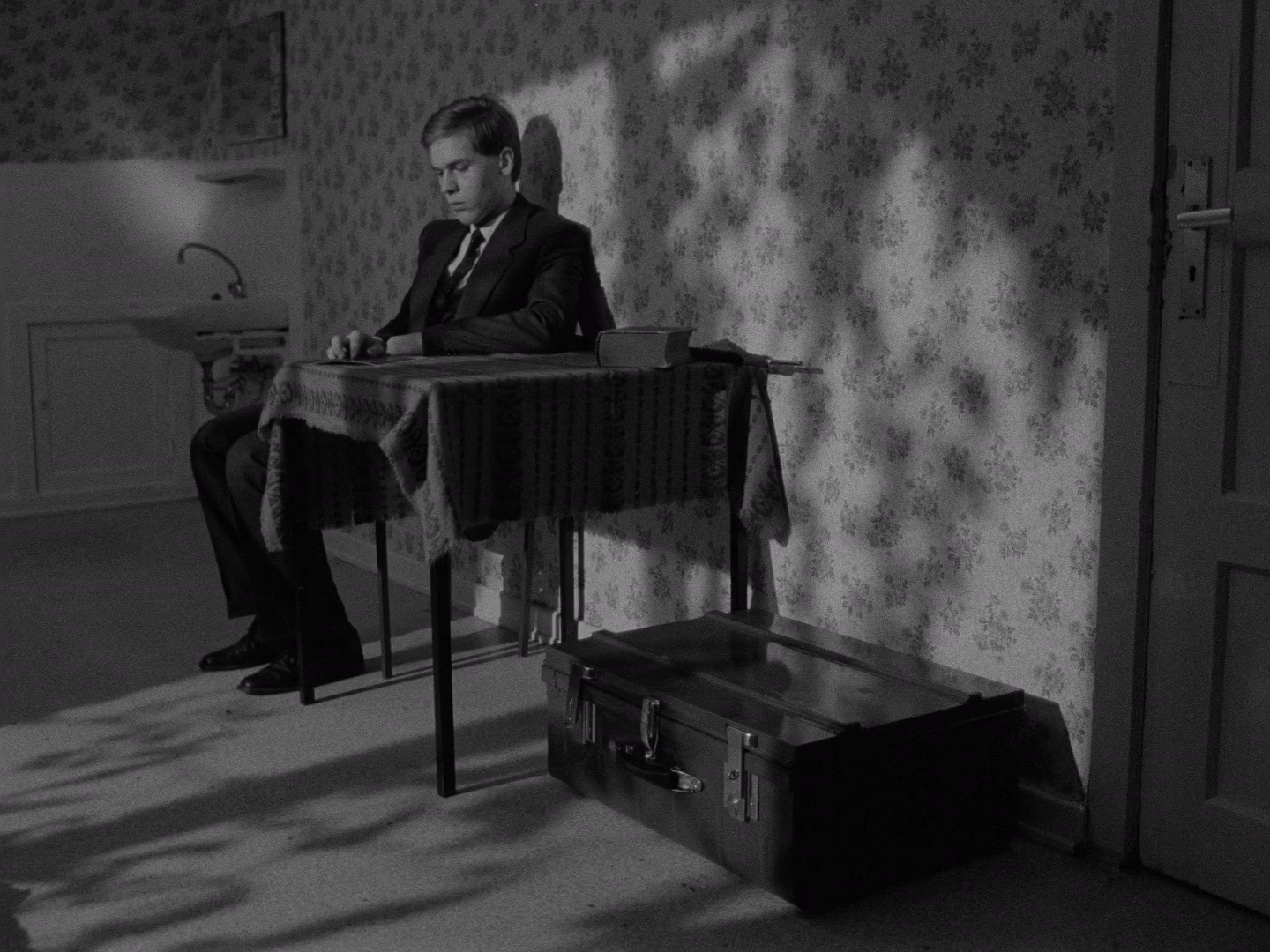

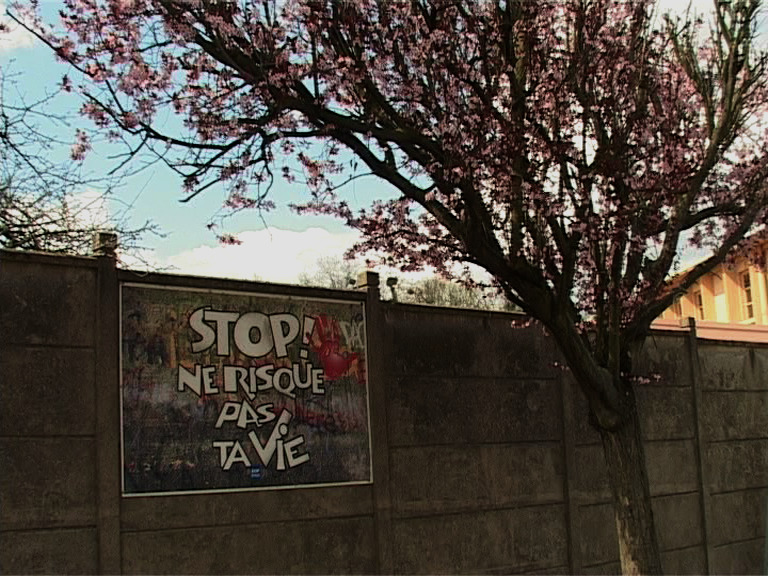

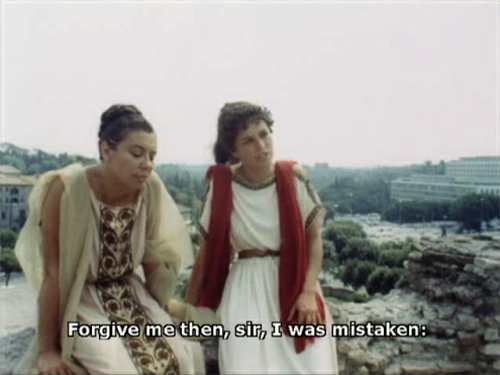

Danièle Huillet (1936-2006) and Jean-Marie Straub (1933-2022) were a French duo of filmmakers who made about twenty films together between 1963 and 2006. Their partnership resulted in a beautiful and demanding oeuvre, which deeply affected the history of cinema. The work of Straub and Huillet is characterised by a rigorous and uncompromising form, which often involved long takes, minimalistic aesthetics, and a focus on text and performance. They were deeply influenced by the works of Bertolt Brecht and sought to create a non-reconciling form of “political cinema” engaged with pressing social and historical issues. “A political film must remind people that we don’t live in the best possible world,” said Straub, “and that the present, denied us in the name of progress, simply continues and is irreplaceable… That human feelings are being plundered in the same way that the earth is being plundered… That the price that people must pay, whether it be for progress or welfare, is much too high and is unjustifiable.”1

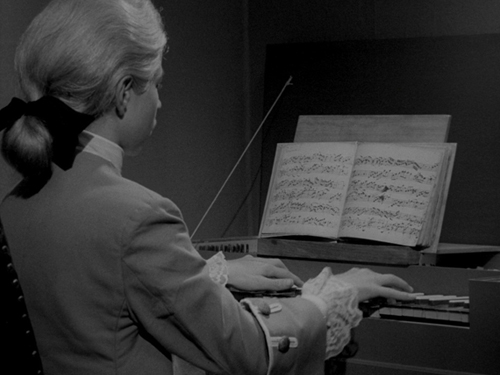

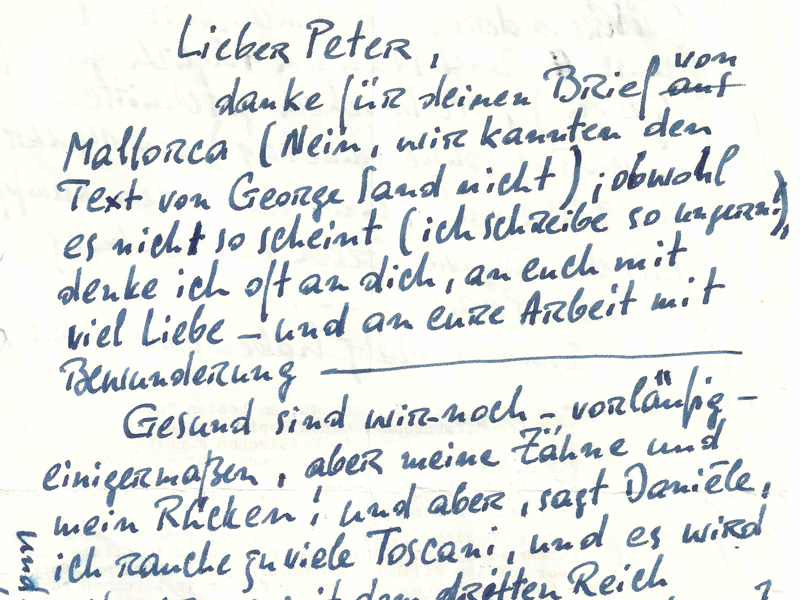

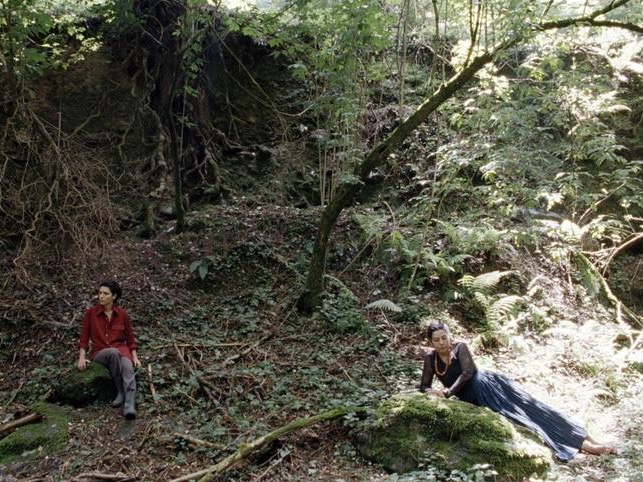

Often grounded in literary texts or musical scores, those of authors such as Brecht, Cesare Pavese, Heinrich Böll, Friedrich Hölderlin or Franz Kafka, their work answers to an ethical as well as an aesthetic principle, reducing the means of staging to their strictest necessity, devoting meticulous attention to detail, particularly in the realms of editing and sound design. Their films often foreground the matter “as such,” whether it’s the chosen text or location, or by working only with direct sound (no dubbing: “Dubbing is not just a technique, it is also an ideology. In a dubbed film, there is not the slightest relationship between what you see and what you hear. Dubbed cinema is a cinema of lies, mental laziness, and violence, because it gives no space to the viewer and makes him increasingly deaf and more insensitive.”2 [Straub]), working with non-professional actors – often chosen for the language, dialect, and place to which they belong, and with natural light which they don’t interfere with.3

Serge Daney, discussing the filmmakers’ pedagogy, contends that non-reconciliation is the foundation from which they crafted their cinema. Instead of simply accepting everything presented in a film, our relationship as spectators and listeners should involve questioning what we observe and hear, pondering its significance and constantly reflecting on its deeper meaning. Their work, Daney continues, relies on “the stubborn refusal of all the forces of homogenization. It has led Straub and Huillet to what might be called a ‘generalized practice of disjunction.’ … Films: the bed where what is disjoint, unreconciled, not reconcilable, ‘plays’, simulates, suspends unity. Not an (easy) art of décalage but the simultaneous head and tail of the one and the same piece, never played, always revived, inscribed on one side (the tables of the Law, Moses), stated on the other (miracles, Aaron).”4

Their best-known films include Chronik der Anna Magdalena Bach (1968), Moses and Aaron (1975), Dalla nube alla resistenza (1979), Trop tot/trop tard (1982), Paul Cézanne im Gespräch mit Joachim Gasquet (1989) and Sicilia! (1999). Following Huillet’s death in 2006, Straub continued to collaborate on Pavese adaptations with the Tuscan theatre group Teatro Francesco di Bartolo in Buti, moved to Switzerland and realized projects already planned with Huillet.

This collection provides an overview of the available texts on Sabzian on the work of Straub and Huillet as well as a complete annotated filmography.5

- 1“Sickle and Hammer, Cannons, Cannons, Dynamite! Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub in Conversation with François Albera,” in Jean-Marie Straub & Danièle Huillet, ed. Ted Fendt (Vienna: Österreichisches Filmmuseum, 2016).

- 2“Intervista con Jean Maroe [sic] Straub e Danielle [sic] Huillet,” Gong; Il mensile di musica e cultura progressiva, Milano, 2 (February 1975), in Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet, Writings, ed. Sally Shafto (New York: Sequence Press, 2016), 156.

- 3See the article ‘What Is a Political Film? On Straub-Huillet’s Poetics of Hylomorphism’ by Bojana Cvejić, Sabzian, 24 July 2019.

- 4Serge Daney, “A Tomb for the Eye (Straubian Pedagogy),” trans. Stoffel Debuysere, Diagonal Thoughts, May 25, 2013. Originally published as “Un tombeau pour l’oeil (En marge de ‘L’Introduction à la musique d’accompagnement pour une scène de film d’Arnold Schoenberg’ de J.-M. Straub),” Cahiers du Cinéma 258-259, July-August 1975).

- 5This collection is indebted to an issue of the film magazine Balthazar, dedicated to the work of Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub, and includes new interview and texts, and a fully annotated filmography. The complete PDF is freely accessible on the website of Balthazar. With thanks to Oscar Pedersen, Viktor Retoft, Balthazar and the authors.