What Is a Political Film?

On Straub-Huillet’s Poetics of Hylomorphism

“Things don’t exist until they have found a rhythm, a form. The form of the body gives birth to the soul. I’ve said it a thousand times. There was this Thomas Aquinas who discovered that, and as he was Neapolitan, he knew what he was talking about. When someone says: “Yes, the form, it’s the form, the form, never mind the idea.” That is a sell-out. It’s not true. You have to see things clearly: First there is the idea. Then there is the matter [matière] and then the form. And there is nothing you can do about that. Nobody can change that! The idea, that’s what Eisenstein had when he organized his sequences. He had his montage of attractions… Then there is the matter. He has to determine the duration of the shots he has stringed together, that is the matter. What we are doing here is the idea that was on paper, the construction of the film, and then we work on the matter. We work with a matter that resists us and you just can’t cut anywhere you like between shot. […] And through this work, the struggle between the idea and the matter […] gives rise to the form. […] The same goes for a sculptor. He has his idea and gets a block of marble and he works the matter. He has to take into account the nervures in the marble, the cracks, all the geological layers in it. He just can’t do whatever he wants.”

Jean-Marie Straub in Où gît votre sourire enfoui? (Pedro Costa, 2001)1

In the famous scene of Pedro Costa’s portrait of the working couple Straub-Huillet, Jean-Marie Straub explains his view on cinematic form: there is first the idea, then comes the matter, and the form is only a third instance, which results from the matter’s resistance to the idea that tries to shape it. Mentioning Thomas Aquinas, the “Neapolitan” who “discovered” the relationship between form and matter, Straub references hylomorphism, Aristotle’s doctrine of being and knowing that preoccupied medieval scholastics and Thomas Aquinas in particular. According to Aristotelian hylomorphism, everything that exists, which is substance, is a compound or composite of matter (hulê) and form (eidos, morphé, schema, rhuthmos). To give a brief account of the expanse of hylomorphic framework, form unifies some matter into an object, form is polis and citizens are matter, and form is to soul what matter is to body.2 “Form” and “matter” seem quaint compared to “form” and “content”, the pair of aesthetic categories that have been domesticated in the common parlance thanks to expression (“form” and “content” of expression).

When we speak of form and matter, as opposed to form and content, we consider genesis to be like individuation, something is generated in nature or composed in artifice through a form that individuates, or in other words, differentiates matter. Hence, there are several reasons why Straub-Huillet’s films should be regarded as hylomorphic (matter-form) compounds in the tripartite scheme (idea-matter-form) drawn above and not in expressionist terms. For starters, a certain formalism is distinctive for Straub-Huillet’s cinematography, in general because of the permanence of a style they are admired or despised for. In a quarrel, characteristic of the role of the raging ideological spearhead of the duo that he plays, Straub rejects formalism. Formalism is arbitrary when it arises from the free will of the artist who thinks they can decide on it. Instead, he insists on the primacy and obligation of matter, as if his method should also be regarded as historical-materialist, according to which artistic material harbors history from within. In Straub’s words, matter’s resistance to idea is like a class struggle, which is dialectically resolved in a form. If Straub-Huillet’s films should be best described as matter-form compositions, or audiovisual objects, does the third term – idea – engender a political cinema? To remain rigorous, as Straub-Huillet’s films are, let us first look at what is matter and what is form in their operation and try to think along with their poetics.

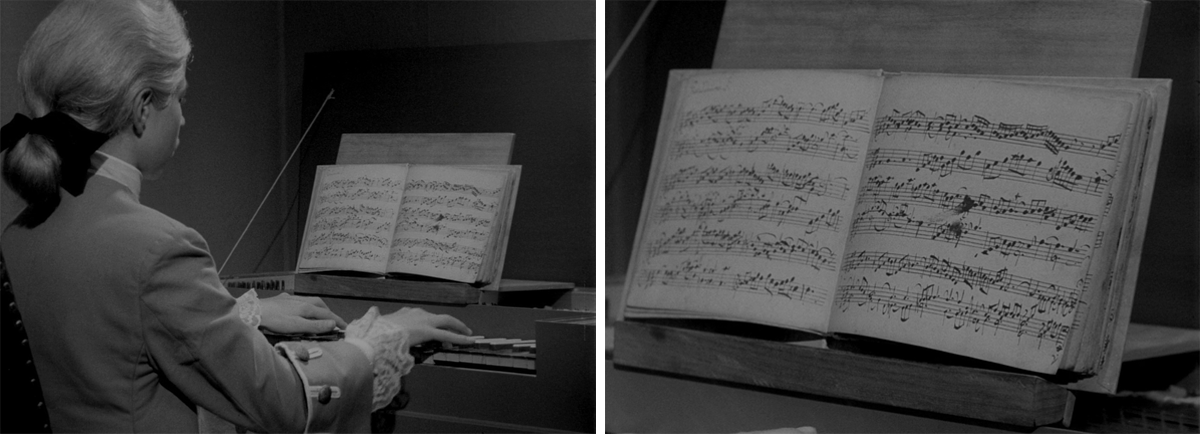

Firstly, Straub-Huillet’s operation foregrounds matter. Matter is music in Chronik der Anna Magdalena Bach [Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach] (1968), live performances of entire compositions that make up the bulk of the film, each one shot in one single take in mono sound system. (The same applies to Schoenberg’s opera Moses und Aron [Moses and Aaron] (1975).) Text is also matter in all their films, as it is used unmodified from a literary work, either in entirety, or as a part, but never cut-up or adapted. Space is found matter, often a result of a long search for a place in which the scenes should be set (driving thousands of kilometers to find the right clearing for a scene, e.g. in Der Tod des Empedokles [Empedokle’s Death] or Moses and Aaron). The matter of space is “respected” through direct sound (no dubbing), because the relationship with what is heard and what is seen is preserved, sound also being matter.3 The distances between the speaking actors are carefully calculated by the shot so that the spectator wouldn’t be fooled.4 Another element of matter are the people that appear in their films. The decision to work with non-professionals rests on two reasons. Non-professionals are found, or often chosen for the language, dialect, and place to which they belong. As such they are the living part of the matter that the audiovisual object must preserve; hence, they are not asked to act a role that would require transformation into character. Straub-Huillet prefer to work with non-professionals (the “not-interesting people”) to working with actors (the “beautiful people”), because “they bring solutions that none of the ‘beautiful people’ would have imagined since they’re not trapped in a present mentality” (Huillet).5 As yet another element of matter, movement pertains to light, often the found natural light of the place of shooting, which they don’t interfere with. Movement is also carried through the gestures of the non-professional actors within the shot, but there it verges on becoming form.

Forming amounts to directing qua composing a film. Contrary to the weight that editing bears in the film apparatus, most of the composition, as a kind of preliminary editing, occurs on the shooting set for Straub-Huillet. A record number of takes per shot attests to this claim, for even when they have reached the version deemed as good, Straub-Huillet record one or two additional takes of the shot just because they are different. This means that they don’t satisfy themselves with what they could get from the live situation of playing in front of the camera, like the directors that will count on the magic of editing. Editing appears as a minimal interference, or else it would distort the living matter they are trying to preserve. Prior to shooting, a long process of rehearsals takes place, whereby directing comes to the fore. Shots are staged with actors, who have learnt the text. The short statement titled Nicht spielen, rezitieren, captures the formal principle with which the actors begin learning text: “…we didn’t ask the actors to ‘perform’ their text in any particular way, but ‘to recite’ it, like a very precise score.”6 Huillet explains that they showed actors how “they could extinguish themselves”. When the actors succeeded at that, they asked them to “develop something, to go out of themselves [Huillet]. When they reached that point, they had to internalize it [Straub].” The actors internalize a text — the resistance of which speaks through them. They are instruments on which the text is played and formed:

An actor is a body that exists and expresses itself when one has the impression that what is being said isn’t even clear to the actor, and that what is said has many meanings and not the same that one wants to impose on it. The actor has become a kind of sleepwalker. That is difficult work. It takes a lot of time and patience, on both sides.7

The kind of work that it takes can be gleaned from Harun Farocki’s documentary of the rehearsals and the shooting of Klassenverhältnisse [Class Relations] (1984), based on Kafka’s America.8 Straub, more than Huillet, frequently interrupts the actors and then tries to illuminate the text. If there is any psychological interpretation that is demanded of the actors, it is in service of the plot and the ideas that Straub interprets from Kafka. The effect that he asks for can be reduced to a shifted accent on a word, for instance, “Auftrag”, which he explains laconically: Auftrag is an important word in Kafka. Sometimes, this requires that he demonstrate the melody of the sentence for the actor – the infamous Vorspiel that directors are supposed to refrain from if they are to allow actors to find their own form. A similar procedure is at work with the gestures, as Straub explains here:

Initially, he [the actor] reads the text over several weeks without even moving his butt out of the chair. Then we tell him: now let’s try it standing up. And then, at a certain moment, when he stares blankly off into space, we tell him: that doesn’t mean anything, why? And then suddenly he raises his eyes and we say to ourselves: but there it works. Afterward, we try to shift it sometimes on a syllable, on a letter, or a word, or on the beginning or end of sentence. This, this takes place well before all the spatial prep work.

Mise-en-scène results from a two-way movement of individuation,

actor [matter] èç director [form]

ê

scene

which seems standard for directing and even commonsensical. However, the difference that Straub-Huillet bring to this process is that they start from an “extinguished” actor, a person that has disindividuated themself, in that they suspend the individualization that for a professional or even wanna-be actor acting a role or building a character entails. Once they have internalized the text, the constraining form of the matter of the text will come out as the resistance or friction that it produces on the body of the actor. This is where the individuation of the actor begins. As Huillet explains, their actors are working people, who show up at 6 p.m. after their day job, exhausted. “Therefore if things work out it’s because they really want them to, they want to discover something else.”9 The discovery for the actor isn’t the form imposed upon them, but the composition that arises in the matter-form compound, in the singularities created through the operation. In that sense, it is a collective discovery of the film, of its actors and directors.

In a critical revision of hylomorphism, Gilbert Simondon discusses the example of molding a brick.10 His revision posits individuation as a process in which two half chains of the operation join from opposite sides, from matter and form at once; how clay as matter is formed from swamp to a plastic material ->, and how the mold is formed from an abstract volume to the shape of the future brick <-.

The main difference in Simondon’s version of individuation lies in the role that form (mold) performs on matter (clay): the form of the brick isn’t imposed but completes the process of deformation internal to clay by interrupting or stabilizing it according to a definitive contour. In this operation, matter isn’t passive: clay is plastic, it contains and transmits force. Force is the third element added to matter and form: it marks the encounter between matter and form as one of a reciprocal exchange of force, in which a series of changes occur. Individuation is complete when the matter has taken form, when all molecules of the clay have reached an equilibrium (a state of internal resonance).

(informed) matter èç (mattered) form

ê

matter-form

We are talking about cinema here, so is directing actors like molding bricks? How could an actor stand in place of clay or brick? An actor is a different kind of matter than the clay of a brick, for the obvious reasons that clay has an invariant set of properties which in molding gives a calculable, stable form. A scene with actors can never be envisaged, planned and realized as in how a brick is made, because the operation of the making of the scene entails people talking back, and all that is being expressed in that moment live. In that sense, living actors are more active matter than clay and thus give a larger scope of differences. Even if rehearsals and repeated takes are designed to stabilize the form, only singularities appear. This is best proven by the extraordinary precedent, that is, Straub-Huillet produced several copies of the same film, different tapes with minute differences in their film, in their fight against Benjamin’s condition of the mechanical reproducibility of a work of art. They refuse to deliver a definitive copy. A film in several copies testifies like a document to the liveness of matter that is preserved in the matter-form compound.11

Apart from liveness, externalism is another formal principle that “liberates” Straub-Huillet’s films to “live” in history. In other words, by carefully shaping an externalist standpoint, the directors are composing an audiovisual object that should exist beyond their ideas and intentions. Externalism begins with the aesthetic attitude that Straub describes as follows:

The job for me when preparing the découpage is to achieve a state that is absolutely empty so that I’m sure to be absolutely devoid of intention, to be stripped of intention when I’m shooting. I’m always in the process of eliminating all intention–personal expression. That’s the purpose of the découpage. Stravinsky said, “I’m well aware that music is incapable of expressing anything.” I think the same is true for a film. In reality, we don’t know what a film is. A film is not there to tell a story in images; it’s become obvious in the meantime; neither does a film exist to show something – an establishing shot doesn’t pay in a film, except very rarely; nor is a film there to express something, feelings or something else. Nor does a film exist – although I’m not absolutely certain – to prove something. In order not to fall into one of these traps, the work of the shot découpage consists in destroying from the outset these different, expressive temptations. Then and only then can you accomplish at the filming stage a real work of cinema.12

As if it wasn’t authored from the epistemic standpoint of Barthes’s death of the author (for example, in Mallarmé or Proust), the work of a film enjoys an autonomy that verges on underdetermination. Indifferent to the goal of convincing the spectator of anything, the least of its raisons d’être to be attributed to a certain message, the work of the film is like a document from the past, even when regarded in the present that it is created in. What else makes up the form of the hylomorphic audiovisual object?

We have mentioned direct sound as matter earlier. However, no dubbing is also a formal principle, since shooting with direct sound acts as a constraining form. As Straub notes: “When you film in direct sound, you can’t allow yourself to mess around with the images: you have blocks of a certain length, and you can’t use the scissors any way you want, for pleasure, for effect.”13 Dubbing was a popular post-productional device in early postwar cinema, also characteristic of some national cinematographies that refused subtitling.14 It is part of a form and a style that Straub criticizes harshly. A dubbed film is

an international product, something stripped of words, onto which each country grafts its respective language. Languages that don’t belong to the lips. Words that don’t belong to the faces. But it’s a product that sells well. Everything becomes illusion. There is no longer any truth. In the end, even the ideas and emotions become false. […] The international aesthetic is an invention and weapon of the bourgeoisie. The popular aesthetic is always an individual aesthetic.15

The interviewer, Enzo Ungari, then concludes: “For the bourgeoisie, there is no art that is not universal. The international aesthetic is like Esperanto.”16 We return again to the preservation of the living matter, this time formulated as the particular. A political film starts with the particular. Or as Straub put it: “Political films start with realism. The kind of realism which, Brecht says, starts with the particular, and only once well rooted in it rises to the general. He said: “Let’s start with the unique item, buttoned up/linked with the general.”17

What is distinctive about Straub-Huillet’s film as a matter-form compound is that it is a political film – not as a genre, but in a peculiar understanding that amounts to Straub-Huillet’s conception and operation of cinema.18 We have already seen the particular of realism, which is part of Straub-Huillet’s definition of a political film. If we are to follow this definition, then there are three more ideas that Straub argues for in his answer to the question what a political film is. “There is no political film without morality, there is no political film without theology, there is no political film without mysticism.”19 These ideas stand in negation of the present state of things. Morality is in crisis today, because “it is replaced by cynicism. Cynicism on the walls, in slogans, commercials… You could even go further and call it the liquidation of public morality.”20 The idea of theology isn’t unrelated to Straub’s argument on morality. As Straub contends, peasants have invented gods, and the ensuing monotheism meant that “it is very difficult to deal without gods”. Again, the solution is cynicism, “an ersatz society, on every level: water, air, feelings, morality, God, everything” amended by “sociology and shrinks to replace confession.” What “theology” does for people is help them “shun phony feelings, [and install – B.C.] the practice of sentimentality and piety”. Thus, it is theology in the oblique sense of Charles Péguy’s words – “I am not pious, said God”21 – which can be retraced in Straub-Huillet’s Moses and Aaron, The Death of Empedocles (after Hölderlin’s play), even Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach. About the third idea, that of mysticism, we are left to wonder and guess: should we regard Straub-Huillet’s faith in history, and therefore, the way that they try to redeem it, as a kind of mysticism? Are Straub-Huillet’s heterodox readings of Bach’s and Hölderlin’s place in history mystical? Is it mystical to side with Benjamin’s (in fact, Paul Klée’s) figure of Angelus Novus who turns his back to the future in order to awaken the dead, recoup the past and thus redraw a present in spite of the storm of progress?22

The answer to this question is not simple. In fact, it requires that we return to the matter-form composite and reconsider it in political terms. Are texts only chosen and dealt with as matter? Straub:

We address ourselves to texts that offer us resistance. We try to test them out; we make audiovisual objects out of them, which consist of movements, movements within a visual frame, movements of light and sound. We are more interested in the music than the ideas. Godard is more interested in the ideas than the music.23

But how do they choose a text? Is there an idea underlying such choice? Different texts yield different music. Using literary texts, or other textual forms, like musical scores and documents, often serves the making of a portrait of either a figure (e.g. Johann Sebastian Bach, Paul Cézanne), a region in a historical time (Lothringen, or German Lorraine), or a point of view expressed in a work of literature or music (Kafka’s America, Hölderlin’s Death of Empedocles, Brecht’s The Business Affairs of Mr. Julius Caesar, Schoenberg’s Moses and Aaron). Their choice points to a view on a history which is dissonant with the present. When Straub-Huillet describe why a figure or a text drew their attention, it is always because they read something irretrievably lost in it for the present time. Thus, Bach is chosen as

one of the last individuals in the history of German culture in whom there doesn’t yet exist a divorce between what is called an artist and an intellectual; you find no trace of romanticism in him – we know what in part resulted from German Romanticism. There is not in him the slightest separation between intelligence, art, and life; neither is there a conflict between sacred and secular music; in Bach, everything exists on the same plane. For me, Bach is the opposite of Goethe.24

Hölderlin was solitary when he expressed his concern for Germany on the threshold of modernity, heading for industrial revolution, a modern nation-state and progress, and this is why Hölderlin and his poetry interests them. For Straub-Huillet, Hölderlin turns to poetry as that which “should give the children of the earth the courage to turn their backs on so-called progress, so-called science – the courage of the revolution, which according to Benjamin is a tiger’s leap, not into the future, but into the past, a tiger’s leap “under the open sky of history”.25

In several interviews, Straub aligns with Benjamin’s redemption of the past. This serves him as a critical departure from the ills of the present time, primarily regarded through capitalist growth and the future hijacked into a present of which people lose sense. The method of their political films is to restore the memory of particular moments in the past, which could shed a critical light on the present. We will cite a longer passage here to illustrate this claim:

Now I want to add one thing to my three earlier points [morality, theology, mysticism – B.C.] and say that there can be no political film without memory. By memory I mean that you have to take a firm stand against social democracy, reformism and all that junk, because the only truth these people refuse is the fact that there ever was a past, that things were different. They are completely anti-Marxian: the Marxian method par excellence consisted of searching all the way back to the Assyrians to find out how things were different, what had changed. And Marx was going further and further as he grew older. On the other hand, social democracy keeps taking flight into the future; people don’t even have the right to experience the present time anymore. They’re being told that progress must go on, that there is no alternative but to rush down into the abyss of progress until disaster takes place. Growth is infinite, it can’t be stopped.26 […] Therefore we live in ‘the best of all possible worlds’ and all that preceded us was necessarily not as good. This is exactly what Walter Benjamin rebelled against when he said that revolution is ‘a tiger’s leap into the past.’ So a political film must remind people that we don’t live in ‘the best of all possible worlds,’ far from it – something Buñuel already said – and that the present time, stolen from us in the name of progress, is going by and is irreplaceable… That the price people must pay, whether for progress or well-being, is far too high, unjustifiable. […] So we must come back to what Benjamin said: revolution ‘is also reinstating very ancient but forgotten things’ (Péguy). Films that make you feel this way are political films. The others are truffe, scams.27

Cinema is political if it is capable of preserving a living matter and thus restoring history in the memory of the present. In that sense, we can extract the hylomorphic schema from Straub-Huillet’s operation of a political film as follows:

1. Out of a critique of the present, Straub-Huillet address themselves to a past which, if redeemed, would change or revolutionize the present.

2. Here, the critique is the formal principle that leads them to history as the matter (hulê). This can be Sicily as it has been lived in the 1960s, the German Lorraine during WWII or the commune of Italian peasants after WWII. It is hard to say what comes first, whether it is the memory of the history (matter) that provides the critique of the present (form) or the critical departure from the present (form) which makes them search into history (matter).

3. The matter-form compound arising from a ‘tiger’s leap’ into history is the idea associated with the choice to work with a text or another work of art: Hölderlin’s Death of Empedocles (for it presents Hölderlin’s critique of the Germany of his time), Elio Vittorini’s Women of Messina, etc.

4. The chosen text is then rendered as one element of the matter that will be treated (and preserved) by the formal devices of their film.

5. Thanks to the idea entrusted to the chosen text/work (redemption of the past in the present as a critique of the present), the audiovisual object is a political film.

History as Matter èç Critique of present as Form

ê

Text as MF matter-form compound = Idea

ê

Matter for a film èç Form for a film

Matter: text, language, people, space, found sounds, movement, light

Form: reciting, direct sound, gesture, costume, mise-en-scène (staging/blocking)

ê

audiovisual object

political film (MF of higher order)

There is one more element to consider for the full definition of political cinema. Nothing of this would be possible without these two filmmakers renouncing and delinking from the film industry. Straub-Huillet insist on the freedom of taking in charge the organization of the work and defining their own terms of production.

Making a film politically means using the lenses you need, the amount of film you need, shooting in the order you need, with the equipment you need. It means paying the crew at least union wage, at the beginning of each week rather than at the end, and not accepting ridiculous budget restrictions at a time when commercial production as a whole is wasting money in incidental expenses and useless stuff. 28

The reason why The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach had to wait ten years to be produced had to do with the stubbornness of Straub-Huillet in resisting the conditions that the producers offered them, interfering with their choices and the very matter of the film.29 From the beginning of their career, they followed Cocteau’s maxim: “You must cultivate whatever it is you’re being criticized for: it is what you are.”30

Straub-Huillet’s cinema is characterized as slow, but the quality of their slowness is different from so-called ‘slow cinema’, comprised of long shots in which an image expires with no action – the contemporary strand that comes out of the cinema of time-images or the cinema of the seer, as Deleuze proffered it. Time in their films is organized deliberately flat. This is most obvious in the pacing of recitation: pauses are inserted in the middle of sentences or verses, sometimes respecting the line-break against enjambment. The regularity of pauses takes out psychological excitement from an utterance and replaces it with a musical tone paced in a steady rhythm. Indeed, we might ask ourselves whether there is a relation between cinema’s temporality and the historical time which is part of the operation of the political film. If we take The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach, its composition alternates between performances of entire musical works (taken in one shot, thus respecting the dramaturgy of a concert performance) and the steady fast reading of the text of letters or diary entries, as if they were paced in the motoric baroque rhythms of courante or allemanda. The idea of making their film resemble Bach’s character and life in which art, life and intelligence are equal on the same plane might be the reason for evening out these rhythms. Straub writes:

If the film really resembles Bach, a total equilibrium incarnate – that’s what I wanted to say, when I said there is no divorce in him between art, life, and intellect, sacred and secular music – if the film becomes also what the man was, then of course it will penetrate right into society’s roots (…).31

He admits that his “biggest fear” was that the “music would create lofty heights in the film”. The music had to “remain on the same level as everything else.” It was chosen “dialectically”, “solely in relation to the film’s rhythm”. In Straub’s words: “I know exactly where I need a flat surface – and there I didn’t choose music that would have put this flat surface, which was necessary, in danger.”32

Slowing down, making the rhythm of each utterance steady, and musicalizing the tone of speech denaturalize the expression of meaning in language. The famous example would be En rachachant, where we might wonder whether the melody of the speech, or the style of expressly sung sentences of the teacher, the parents and the child, exposes French Republican pedagogy, its perverse ideal of value, and the ironic response of the child who refuses to be instructed. Straub-Huillet draw special attention to words by according each phrase an equal amount of time, so that the present would be felt like being processed by a slow grinding machine. This formal operation de-eventalizes instants, evening them out in a persistent present in which the spectator is caught. No ellipsis, no dramaturgy of suspense, a brake put on action’s progress – all accents and highs and lows are in the meaning of the words in so far as the spectator can receive them and think them. Perhaps the effect of this operation is to restore the right of the spectator to experience the present time as that which endures in a film, even if the film’s time represents history.

- 1Quoted from Pedro Costa’s film Où gît votre sourire enfoui? [Where Does Your Hidden Smile Lie?] (2001).

- 2At a glance, Straub’s quote above seems to contradict the hylomorphic scheme: “The form of the body gives birth to the soul.” For a filmmaker, the body is the form to the soul, and not vice versa, as the body is what he will register in the film. This reversal still fits in the hylomorphic scheme: form and matter are enmeshed; the body is in-formed and en-souled and the soul is mattered.

- 3Straub writes: “Dubbing is not just a technique, it is also an ideology. In a dubbed film, there is not the slightest relationship between what you see and what you hear. Dubbed cinema is a cinema of lies, mental laziness, and violence, because it gives no space to the viewer and makes him increasingly deaf and more insensitive. Every day in Italy, people are becoming deafer at a terrifying rate.” “Intervista con Jean Maroe [sic] Straub e Danielle [sic] Huillet,” Gong; Il mensile di musica e cultura progressiva, Milano, 2 (February 1975), In Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet, Writings, ed. Sally Shafto (New York: Sequence Press, 2016), 156.

- 4Even in Straub-Huillet, realism requires additional proofs. Straub: “In filming with direct sound, you can’t fool with the space, you have to respect it, and in doing so offer the viewer the chance to reconstruct it, because film is made up of “excerpts” of time and space.” Straub and Huillet, Writings, 158.

- 5“Sickle and Hammer, Cannons, Cannons, Dynamite! Daniele Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub in Conversation with François Albera,” Hors Champs the Locarno Film Festival (August 2001): 109-25. Ted Fendt, ed., Jean-Marie Straub & Daniele Huillet (Vienna: SYNEMA, 2016), 121.

- 6“Nicht spielen, rezitieren,” Film: eine deutsche Filmzeitschrift, 5 (May 1965), In Straub and Huillet, Writings.

- 7Originally an oral exchange between the filmmakers and the public in Avignon, following a screening of The Death of Empedocles in 1987.

- 8Jean-Marie Straub und Danièle Huillet bei der Arbeit an einem Film nach Franz Kafkas Romanfragment „Amerika“ (1983) [Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet at work on Franz Kafka's “Amerika” (1983)] Straub-Huillet’s film called in the German version Klassenverhältnisse.

- 9“Sickle and Hammer,” 21.

- 10Gilbert Simondon, L'individuation à la lumière des notions de forme et d'information (Grenoble: Éditions Jérôme Millon, 2013). See chapter 1 (Forme et matière) in Part 1 (L'individuation physique), “Fondement du schème hylémorphique. Technologie de la prise de forme.” Foundations of the hylomorphic schema. Technology of 'taking form' [la prise de forme], Simondon, 39-51. Simondon’s obscure legacy in contemporary continental philosophy is handed down through the work of Gilles Deleuze, Isabelle Stengers, Alberto Toscano and a few other philosophers who credited his influence.

- 11The Death of Empedocles is the film that exists in several material copies. This fact mirrors Hölderlin’s process of rendering several versions of texts, in this case four different versions of his play The Death of Empedocles.

- 12“Tribüne des jungen deutschen Films: III. Jean-Marie Straub,” interview by Frieda Grafe and Enno Patalas, Filmkritik, 119 (November 1966): 607-610; Straub and Huillet, Writings, 70.

- 13Straub and Huillet, Writings, 158.

- 14Italy, for instance. In Jean-Luc Godard’s Gay Knowledge [Gai Savoir, 1969], one of the two activists, played by Jean-Pierre Léaud, announces that he is going to set a bomb in a cinema in Rome, to restore the real sound to the Italian people who have never heard it in cinema.

- 15Straub and Huillet, Writings, 159.

- 16Straub and Huillet, Writings, 160.

- 17“Sickle and Hammer,” 109-25.

- 18As a genre, Straub-Huillet remain reserved about militant cinema that reacts to the circumstances of daily politics, because a film cannot be so arrogant to deliver a recipe for a political change that its spectators should follow.

- 19“Sickle and Hammer,” 109-25. Fendt (ed). Jean-Marie Straub & Daniele Huillet, 109.

- 20Ibidem, 118.

- 21Ibidem.

- 22Gerard-Jan Claes suggested to me an alternative meaning of Straub’s statement on mysticism. I quote Claes from our email correspondence (22 April 2019): “the ‘mystical’ aspect of Straub’s work also links up with a certain ‘belief’ or ‘love’ for the present. I thought of this citation by Buñuel in which he claims that he hopes his films would indicate that we are not living in the best of possible worlds but also convey that the current world is not the only world 'on offer'. Since cinema always works with present ‘things’ and people, he seems to think that it needs to begin from a nearly material love for reality itself, an attention to the intensity of the everyday, thereby redrawing the contours of the possible, to construct a new common world. I wonder whether this is the moment where the ‘mysticism’ steps in.” Claes supports this reading by the following quote from Straub: “When you watch a film, you should be experiencing simultaneously a maximum of pleasure and a maximum of revulsion about life. If you always push the same button, it’s not very interesting. In so doing you can make a career, but that’s all. Whereas if you do like Renoir, each film is different, you’re expanding the range of feelings. On the one hand, a physical impression of the joy of life, and on the other hand – like Buñuel used to point out – the idea that we don’t live in the best of all possible worlds. Otherwise, it’s better to change jobs. In order to do this, you need courage, without any kind of exaltation, to materialise in the aesthetic material, in the film. This is the reason why – although I’m neither an expert nor a specialist – I consider Cézanne to be the greatest painter ever. He managed to materialise on canvas a maximum range of sensations, as he called his personal reactions looking at a tree, or a woman, or a mountain.” (Straub quoted in Claes).

- 23Straub and Huillet, Writings, 207.

- 24Ibidem, 74.

- 25Ibidem, 209.

- 26“Sickle and Hammer,” 109-25. Fendt (ed). Jean-Marie Straub & Daniele Huillet, 110.

- 27Straub en Huillet, Writings, 111.

- 28Ibidem, 117.

- 29They were recommended to work with celebrity musicians at the time like Herbert von Karajan and Nikolaus Harnoncourt, which they refused. Eventually, they found Gustav Leonhard, who was a less known musician, multi-instrumentalist, who pioneered a historicist approach to interpretation based on playing period instruments.

- 30Straub and Huillet, Writings, 116.

- 31Ibidem, 74.

- 32Ibidem, 70.

This text was written after studying hylomorphism with a group of philosopher-friends at Nesin Mathematics Village in Şirince Turkey in early September 2019. Thus, I thank Austin Gross, Jordan Skinner, Matt Hare, and David Bremner for prompting me to answer their question: how is Straub-Huillet’s political film a different hylomorphic composite from any other audiovisual object?

Images (1) and (2) from Où gît votre sourire enfoui? (Pedro Costa, 2001)

Images (3) and (4) from Chronik der Anna Magdalena Bach (Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, 1968)

Images (5) and (6) from Jean-Marie Straub und Danièle Huillet bei der Arbeit an einem Film nach Franz Kafkas Romanfragment “Amerika” (Harun Farocki, 1983)

Images (7) and (8) from Moses und Aron (Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, 1975)

Images (9), (10), (11), (12), (13) and (14) from Der Tod des Empedokles oder: Wenn dann der Erde Grün von neuem Euch erglänzt (Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, 1987)