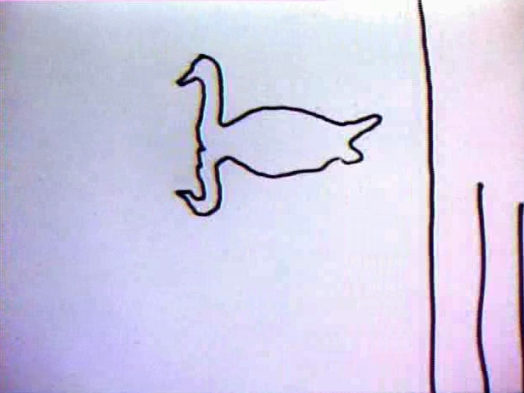

Robert Breer’s first use of the rotoscope. The drawn images are characteristic of a banal home movie of a beach vacation, yet they are seen and treated as isolated fragments. Parts of objects, people, and movements are intertwined into an assemblage of abstract color forms.

EN

“In Gulls and Buoys, a large number of Breer’s ideas are compressed and crystallised into a short statement of great richness. It could function excellently as an introduction to the remarkable range of pleasures available from the films of Robert Breer.”

Scott Hammen1

Bob was the son of an inventor, and in certain circles (automotive rather than artistic) the father’s fame outshone the son’s—primarily, as I recall, for breakthroughs in the aerodynamic streamlining of car bodies. When I first mentioned our OpenEndedGroup forays into 3-D projection, Bob recalled his dad’s having invented his own 3-D movie camera for anaglyph viewing: Breer family movies of the ’30s were as likely to be in 3-D as not. Bob inherited this Breer knack for tinkering, and when my daughters used to explore his studio with him (so much more interesting than my own, with its bland stacks of hard drives), they marveled over all his gadgets: the mutoscope viewers, the glacial floats, the useful little mechanical device he’d made to speed up the slow process of animation: a card flipper that would plunk down a hand-drawn card for quick single-frame capture by the lens before grabbing the next.

This tinkering brought Breer close to the materiality of the medium, which in turn allowed him to see it anew. In films such as Gulls and Buoys (1972), Fuji (1974), and TZ (1978), he made incomparable new use of the tired-out and nearly forgotten animation technique of rotoscoping, using felt-tip markers to trace the successive contours of movements caught in film footage. But rather than the enhancement of realism that this technique allows, what intrigued Breer was its collapse. In Gulls and Buoys, as the flickering hand-drawn contour of a swan’s neck, simplified down to a single elegant curve, merges with its watery reflection, it drowns its own likeness. An ineffable moment that lingers even through the tumult of the frames that follow.

Paul Kaiser2