“Oh, there’s nothing so different about them. After all, crime is only a left-handed form of human endeavor.”

Louis Calhern’s Alonzo Emmerich

“That ‘Asphalt Pavement’ thing is full of nasty, ugly people doing nasty, ugly things. I wouldn’t walk across the room to see a thing like that.”

MGM boss Louis B. Mayer1

“Huston was 43, and he was one of the most interesting, wild men in Hollywood – a rare breed. Of course, he was the son of the actor Walter, and he had been looked after in his time: when he killed a guy in a driving accident, it was covered up. You would have thought that locked Huston into the system. But he was his own man – a gambler, a bit of a sadist, a boxer and a horseman, a painter, a collector of this and that, including women, the most hellacious good company but not truly sociable or benevolent. He was a loner, with dark moods and a lurking criminal bent.

Marilyn Monroe read for the director. She was brought in by Johnny Hyde, her agent, lover and pimp: ‘Just take a look at her, John.’ She made a hash of it. She said, ‘I’m sorry, that was awful, I'd like to try again.’ ‘Well, darling,’ Huston said. ‘You do that.’ And she kept on trying, and Huston was clearly taken with her and not disposed to look elsewhere. People told him the girl couldn’t act, but he said if they used her carefully it would be a few minutes before anyone noticed that. And a few minutes would be enough, because the girl knew she was a jungle creature. And the picture is famous for being her break.”

David Thomson2

“John Huston gave her a helluva good role. Jesus, she was good in it. I thought it must have been the magic of Huston because I didn’t think she had all that in her. But then I put her in All About Eve (1950) and she was an overnight sensation.”

Twentieth Century-Fox boss Darryl F. Zanuck on Marilyn Monroe

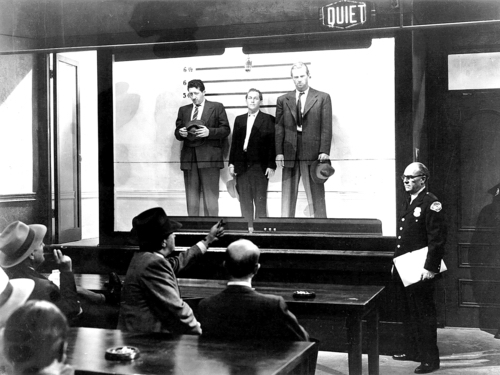

“The Asphalt Jungle, which represents some of Huston’s best work of the 1950s, is a noir observing the build-up and aftermath of a jewel heist, taking considerable interest in both the process of the vault-cracking and the workaday lives and dreams of its gang of double-crossing crooks, including a superb, oleaginous Louis Calhern as their old-moneyed backer, the whole affair owing not a little to Huston’s own 1948 The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.

Huston pushed the boundaries of realism as far as permissible within the studio machine, and along with Elia Kazan he was one of the day’s innovators in location shooting, here filming exteriors in his mother’s hometown of Cincinnati – though most of the rather palaver-heavy movie takes place in seedy rented lodgings, police offices and storage rooms.”

Nick Pinkerton3

“With cameraman Harold Rosson, John shot nearly the whole picture in close shots, scrutinizing faces, movements of lips, and gazes. Dialogued scenes were often filmed with three characters. Sometimes the speaker is not even in the frame and the camera records not only the others' reaction but various connivances and complicities that freeze certain others out of new tenuous alliances. Nearly the whole picture takes place at night allowing sources of light to play a psychological role.”

Huston's biographer Axel Madsen4

“Apparently influenced by French 1930s films like Le Quai des Brumes (Marcel Carné, 1938), with their operatic underworld portraits getting lost in the gray trashiness of back rooms, Asphalt Jungle is just as inventive as Huston’s other job-oriented films in its selection: a top-flight safe-cracker wears a magician's coat honeycombed with the tools of his trade – monstrous crowbar for prying open a manhole cover, three-eight-inch mortar chisel for separating bricks, lapel-anchored cord for safely suspending the bottle of nitro (no jostling, as any student knows), extra bits for his electric drill. Few directors project so well the special Robinson Crusoe effect of man confronted by a job whose problems must be dealt with, point by point, with the combination of personal ingenuity and scientific know-how characterizing the man of action. Two exquisite cinematic moments: the safe-cracker, one hand already engaged, removing the cork of the nitro bottle with his teeth; the sharp, clean thrust of the chisel as it slices through the wooden strut.

Throughout this footage, Huston catches the mechanic’s absorption with the sound and feel of the tools of his trade as they overcome steam tunnel, door locks, electric-eye burglar alarm, strongbox. It is appropriate that the robbers dramatically subordinate themselves to their instruments and the job at hand, move with the patient deadpan éclat of a surgical team drilled by Stroheim.”

Manny Farber5

- 1Cited in Eddie Muller’s seminal noir study, Dark City: The Lost World of Film Noir (1998, p. 147), which has a shot from The Asphalt Jungle on its back cover. Louis B. Mayer, whose taste was largely out of fashion in Hollywood by that time, told this to MGM’s executive in charge of production, Dore Schary. Within months, Schary would dethrone Mayer as MGM chief in 1951. Mayer originally slated Huston to direct Quo Vadis? in Rome, with Gregory Peck and Elizabeth Taylor in the leads. Huston planned and filmed The Asphalt Jungle while they were waiting for Peck to recover from an eye infection. “Suppose we do The Asphalt Jungle, a nice little book by W.R. Burnett,” Huston tried. Quo Vadis? was eventually made without the participation of Huston, Peck or Taylor in 1950.

- 2David Thomson, “The hood, the bad and the ugly,” Sight & Sound, vol. 16 issue 11 (November 2006): 8.

- 3Nick Pinkerton, “Home Cinema New Releases. The Films of John Huston: The Asphalt Jungle and Moby Dick,” Sight & Sound, vol. 27 issue 2 (February 2017): 99.

- 4Axel Madsen, John Huston: A Biography, Garden City: Doubleday, 1978.

- 5Manny Farber, “John Huston,” Negative Space. Manny Farber on the movies (London: Studio Vista, 1971), 34-35. Though robberies were an integral part of most crime films, The Asphalt Jungle was the first to concentrate completely on the recruiting for and planning of a robbery, treating this as important as the job itself. Farber speaks of Huston’s “documentary invention” of the robbery.