EN

John Isaacs in his short documentary The Art of Lotte Reiniger (1970): The Adventures of Prince Achmed was the first full-length animated film in the history of the cinema. It was made by Lotte Reiniger between 1923 and '26 in Potsdam, Germany. For the past 20 years or so, she’s been working in her studios in Barnet. Here she has produced one after another of her unique silhouette films, the technique of which she was the pioneer. Since Miss Reiniger made Prince Achmed, she has made over 40 films, all using simple variations of the basic technique and simple though this technique might seem, it is in the subtleties of its application that its success is achieved.

Reiniger: Here I am to tell you about what l shall have to do to make a silhouette film. First of all, select an idea, which I like to do very much for the work takes a very long time. Let us make Papageno.

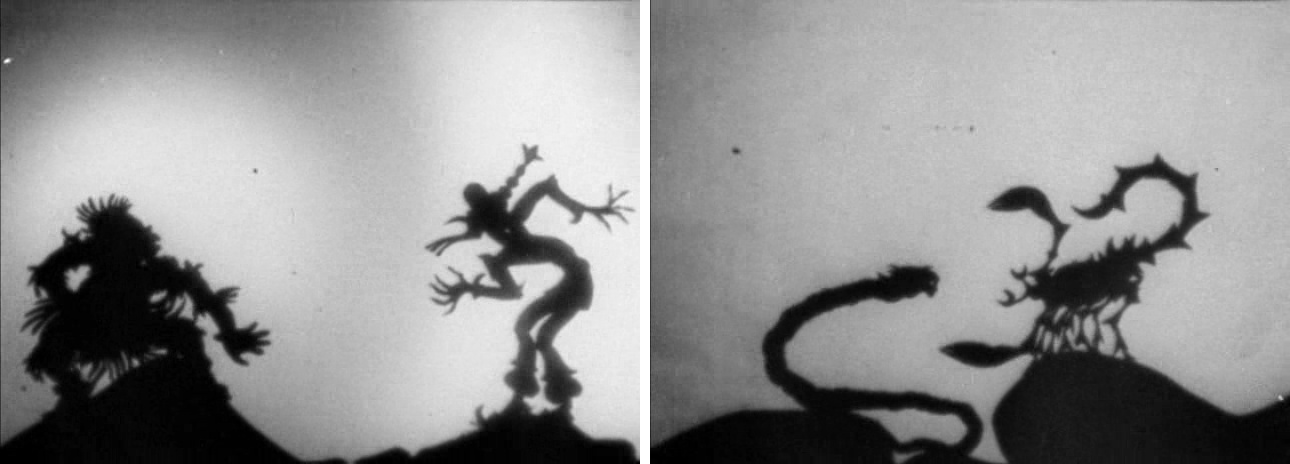

Isaacs: The chosen character, Papageno, has first to be fitted into the story and for this, the various sets and figures are designed. These eventually complete the final storyboard, the blueprint for the film, showing the different sequences which will later be further broken down into the particular movements of the figures. Despite the intricate nature of her specialised technique of filming, the importance of the story must not be underestimated in Miss Reiniger’s work. The magic of the fairy tale has always been her greatest fascination, yet her own interpretations have been a unique quality. Once it is decided how Papageno will look, Miss Reiniger can begin to cut out the figure.

First his head with its feathery headdress, for Papageno is a bird catcher and must look like a bird in order to carry out his profession. The original film of Papageno is taken from the sequence of Mozart’s opera, which she made in 1935. The figures she cuts out were originally inspired by the puppets used in traditional eastern shadow theatres, of which the silhouette form is the logical conclusion. And nowadays much of her time is devoted to staging shadow theatre plays, yet it is remarkable how little the technique has changed. The material, the black cardboard, the scissors remain the same as for her earliest films, the first of which she made in 1917.

And then the whole figure and his costume are cut out in individual sections. The number of separate pieces does, of course, depend on the amount of movement that is required of the figure. Papageno, being a particularly important character, is a particularly complex construction. First, small holes are pierced in relevant points. All these limbs and pieces of costume are joined together with small wire hinges. The hinges are intricately tied, for it is essential that they successfully withstand the constant movement demanded of them. When such a hinge is subject to excessive use, it is weighted with flat pieces of lead which helps also, of course, to keep the figure flat, or otherwise it might warp under the heat of the camera lights.

And then the whole figure is rolled out flat. Despite the speed of the construction, Miss Reiniger will continue to have a strange affection for each of her figures, an understandable affection, for in their flexibility, they have almost human characteristics of movement. These movements are checked standing, sitting, kneeling, hopping and so on. Now he can be filmed. And for this he must be placed upon the table.

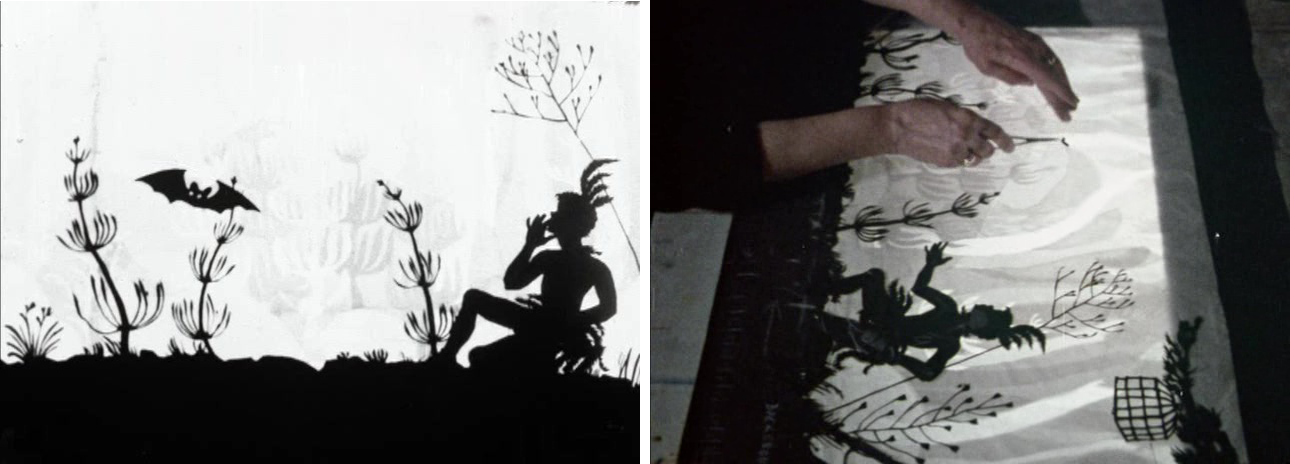

Reiniger: This is a trick-table. If you don’t have such a thing at home you take your best dining table, cut a hole into it, put a glass plate over it, and over the glass plate some transparent paper, and then you put some light on from underneath. And then you switch the other light in the room out, then you see the story, that your figure now is the real silhouette.

Isaacs: To make the figure move, it must be placed in the correct position and a shot taken. The figure is then moved a fraction further and a second shot is taken and so on, so that with much patience and concentration the figure moves more and more.

The camera shutter opens again and again and the final result will be the figure moving across the screen.

There is, of course, a great deal more to it than this. For example, among the specialised techniques which may have to be employed if there’s a possibility of the figure turning. Moving, as seen before, it is first necessary to mark his position. The next step is to turn its head, take a picture and then gradually, the limbs turned one by one and pictures taken. We can now proceed to move in the opposite direction. Alternatively, one can cheat a little by turning the figure as another figure passes in front of him.

Because the camera is fixed, and besides to put too near to small figures would make the outline appear too rough, to cheat close-ups it is necessary to construct an entirely new version of the original figure. In this way, the expression of the figure may be altered in close-up.

As this is a profile art, the action is composed so that the effects of distance or depth are avoided to maintain a purity of style. But these magical figures must sometimes come into the picture from nowhere. For this effect, the shape of the figure must be repeated in numerous different sizes, all numbered. Starting with nothing, the smallest of the figures is placed on the set, a shot taken and the next in the series put in its place. Gradually the figure will reach its destination and appear full-size on the screen. This effect can be used for all kinds of transformations and appearances.

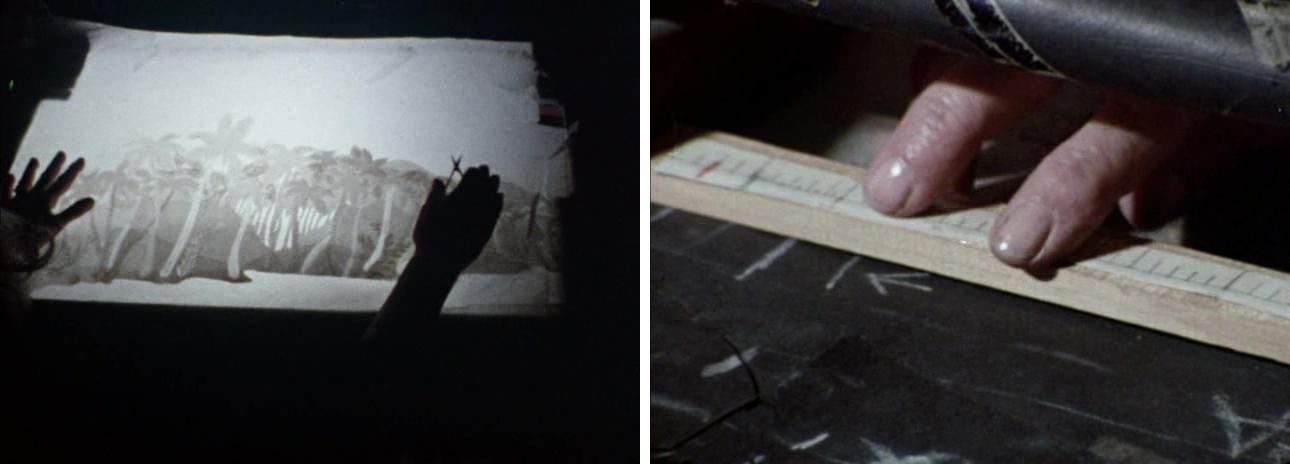

One of the most important tools of the technique are the scissors. And it is in the construction of the backgrounds that the scissors play one of their most vital roles, constructing the different layers and thicknesses of transparent paper. Over all these layers is placed a single sheet of paper to give the figure freedom to move. And for the clouds and water a second glass plate is used, so that these can appear slightly out of focus.

One of the most important tools of the technique are the scissors. And it is in the construction of the backgrounds that the scissors play one of their most vital roles, constructing the different layers and thicknesses of transparent paper. Over all these layers is placed a single sheet of paper to give the figure freedom to move. And for the clouds and water a second glass plate is used, so that these can appear slightly out of focus.

Bearing in mind that the camera is fixed, it must be emphasised that in order to create panning effects, it is necessary to move the whole set. Each movement is charted on a ruler so that the movement of the set is coordinated with that of the figure.

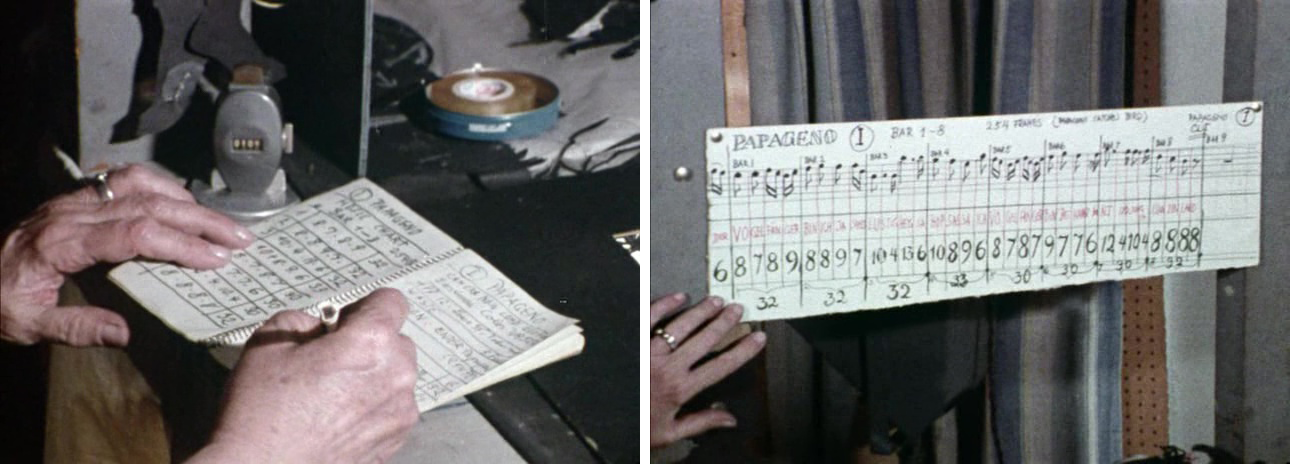

During the shooting, each frame is numbered and recorded in the shooting book so that the number of shots corresponds with the music and the movements. Or if the action fitted to the music like a ballet, with the sound recorded beforehand, then from the score, a particular number of shots accords to the length of each part. This carefully calculated, shooting of the film may proceed so that this delicate balance of musical notes, individual movements of the figures and of camera shots will produce the harmony which characterises the films of Lotte Reiniger.