The artist Antonio López tries to capture the sunlight hitting his quince tree all autumn, but the struggle seems futile.

“I’m in Tomelloso, in front of the house where I was born. On the other side of the square there are some trees that never grew there. In the distance, I recognize the dark leaves and golden fruits of the quince trees. I see myself among those trees, together with my parents, accompanied by other people whose features I don't manage to recognize. The murmur of our voices reaches me, as we chat peaceably. Our feet are sunken into the muddy ground. Around us, suspended from their branches, the wrinkled fruits hang ever softer. Big blotches make inroads upon their skin, and in the still air I notice the fermentation of their flesh. From the place where I observe the scene, I cannot know if the others see what I see. Nobody seems to notice that all of the quinces are rotting beneath a light that I don’t know how to describe: bright, and at the same time somber, which turns everything into metal and ash. It isn’t the light of night, nor is it that of twilight, nor that of dawn.”

An account by Antonio López in the “Painter’s Dream” sequence of El sol del membrillo

“Dear Víctor,

You must know I’m one of the admirers of your film The Quince Tree Sun. I know that when you and Antonio López were making the movie, the attention of the two of you was focussed on the quinces that remained under the tree, rotting, at the end of the film.

For this reason maybe you didn’t realise that there was a branch with a quince on it in the street that was seemingly to have another fate. In our culture, if the fruit hangs outside the four walls of a garden it belongs to the people passing by. Here we see two boys who are a bit older than Antonio López’s grandchildren and who are more interested in eating the quince than in painting it. And they turn it into a target.”

Abbas Kiarostami1

“We didn’t actually talk very much at all. Remember that the task of a painter is a solitary process, totally in contrast to a filmmaker. Time, too, is different for a painter; he has his own time and so can use it with impunity. But for the filmmaker, it’s closer to an industrial process. He’s surrounded by people and doesn’t have the privilege of individual time. It’s collective time and counted out in pennies. I was aware that our presence – the cameras, sound people and so forth – was modifying both the way Antonio could work and his private experience with the tree he was painting. Though I tried to respect as much as possible this relationship between painter and tree – obviously very mysterious, and something which I tried to express at the end of the film – I felt that the crew, while we were only six, could not but interfere in some way. This is why I showed a film camera at the end, to show my work-tool, as it were. I even insinuate that it is our artificial lighting rotting the fruit on the tree.”

Víctor Erice2

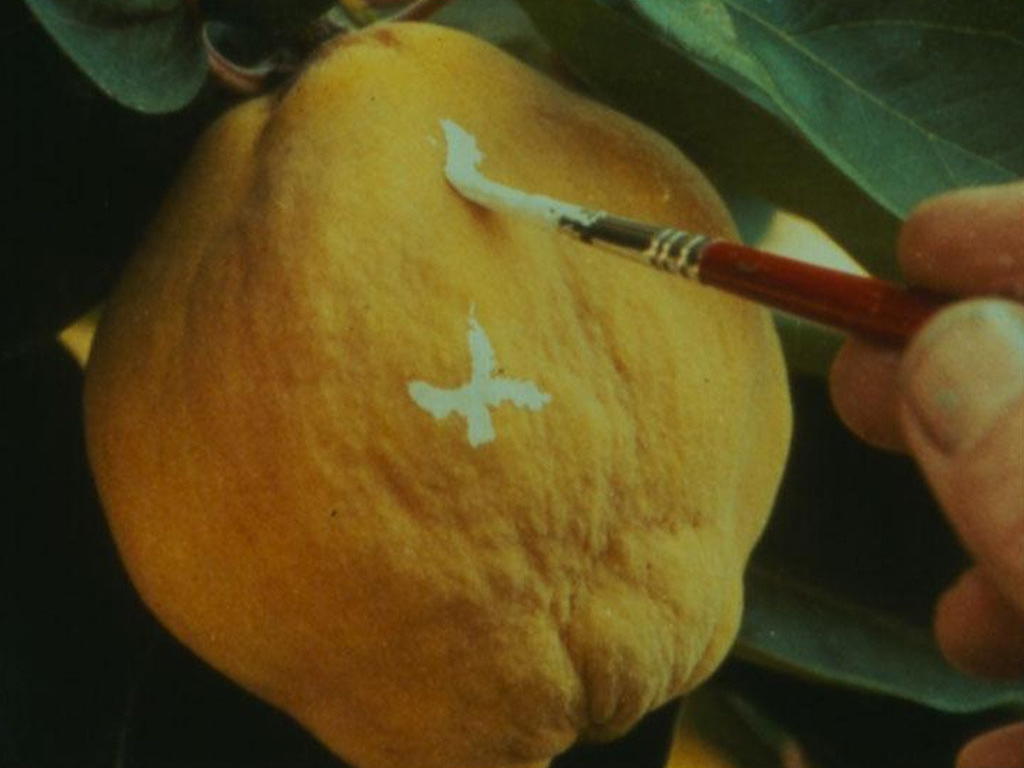

“After the childish reveries of The Spirit of the Beehive and The South, The Quince Tree Sun marks the moment of the amicable confrontation ofthe cinema with its eternal rival, painting, which Erice takes to be the outright winner. In the little garden of a suburban house, while some workers busy themselves on a building site, Antonio López attempts to paint a quince tree. The film chronicles this labour from day to day, yet without claiming a neutrality it cannot in any case lay claim to. It is perhaps the artificial lights used for filming that have caused the fruit to go rotten before the painter was able to finish his picture. The more the camera approaches, the more the image is adversely effected, because the camera “rots the natural”, says Erice. The quinces are akin to memories, with the lustre of the first day of the cinema, and if The quince Tree Sun is a treatise on joyfulness it also recounts the weight of things (the white paint marks on the yellow skin of the quinces, which serve to mark the progressive sagging of the tree bending beneath the weight of its fruit) and the death to come.”

Jean-Philippe Tessé3

“Erice, who has always liked to have actors and non-actors performing together, has, in The Quince Tree Sun (1992), made a film in which it becomes impossible to distinguish between the real people (who play their own roles) and the fictional aspect that turns them, despite everything, into film characters. When Erice films the painter’s dream, he behaves like a pure fiction filmmaker, this dream being an absolute creation of cinema, as arbitrary as the dreams of Buñuel’s or Hitchcock’s characters.”

Alain Bergala4

“Dismantling genres, shattering narrative structures and the ‘naturalness’ of filmic expression; distancing the cinema from the narrative tradition of literature, uniting it with the common ground it shares with pictorial representation; investigating, tautening, capturing time; involving the viewer by means of ingredients other than surprise, suspense, artifice – this is a programme, modernity’s own, that Erice lays claim to.”

Casimiro Torreiro5

- 1Abbas Kiarostami, “The Quince”, Erice-Kiarostami: Correspondances, (Barcelona: Actar-D, 2006), 84.

- 2Víctor Erice in conversation with Geoff Andrew, “The Quiet Genius of Victor Erice”, Vertigo, 2004.

- 3Jean-Philippe Tessé, “On the difference between an image”, Erice-Kiarostami: Correspondances, (Barcelona: Actar-D, 2006) 25.

- 4Alain Bergala, “Erice-Kiarostami. The Pathways of Creation”, Rouge, 2006.

- 5Casimiro Torreiro “Los trabajos, los dias, el tiempo”, El Pais, 10 January 1993, p. 33. [Traduction by Alberto Elena.]