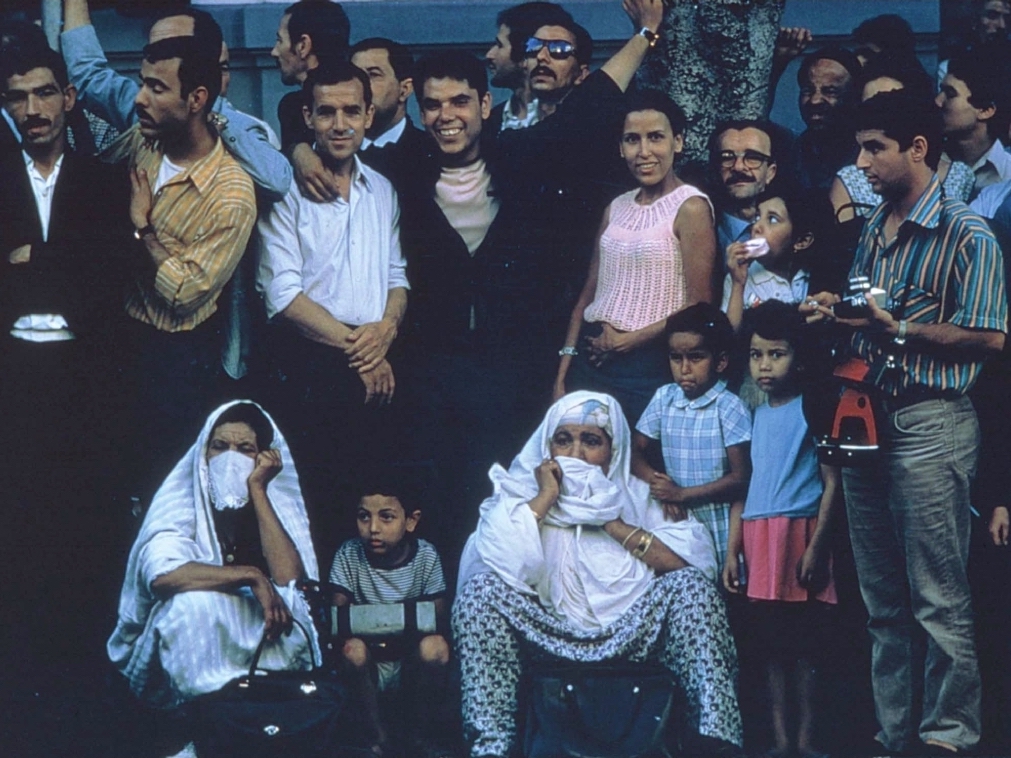

Algeria was in the late 60s the rallying point for all the world’s revolutionaries. At that time, several colonies were still fighting for their independence, and the South African apartheid regime continued to dominate the region. In 1969, Algiers organised what was to become the most notable cultural event in Africa, the first Pan-African Cultural Festival. Each African country is represented by one cultural group, and they sing and dance in their amazingly varied forms throughout the streets. This is another time, a time where the streets still belong to the people. Through the film we sense the intense feeling of communion as we watch artists, poets, musicians, writers, revolutionary freedom fighters talking, meeting and jamming together. The mood is infused with a militant spirit.

EN

“The Pan-African Festival of Algiers takes the form of an essay, thus giving coherence to a huge quantity and range of rich visual materials: posters, photographs, drawings, archive footage of African anti-colonial struggles drawn from newsreel or earlier films, as well as sequences taken from the 1969 festival, such as interviews, rehearsals, concerts and speeches.

Just as its direct inspiration, La hora de los hornos (Fernando Solanas & Octavio Getino, 1968), The Pan-African Festival of Algiers synthesises, rethinks, radicalises and dialecticises that which came before in terms of militant cinema in relation to a given situation and space (in this case, Africa and Latin America), in order to inscribe it within a new history that is both cinematic and political.

The Pan-African Festival of Algiers is a polyvocal text. It makes use of a montage of archive images but also includes extracts from documentaries by René Vautier or Lionel Rogosin. [...] The film is thus an amalgam of a group of films that together constitute a little-known history of cinema associated with the liberation of Africa. Animated inter-titles, the use of drawings, photographs, posters, still images, reframing and sequences of ‘direct cinema’ add other perspectives and the result is highly dynamic. The use of montage and inter-titles resembles the graphic style and rhythm of Soviet films at the end of the 1920s, reread through the Latin American revolutionary cinema of the 1960s, as embodied by filmmakers like Santiago Álvarez or Solanas and Getino.

Never giving the impression of being too rigid, nor bombarding the viewer with slogans, the film is more like a luminous patchwork of the aesthetics of the pamphlet, of agit-prop and of direct cinema. A rhythmical editing style, at times rapid and incisive, at other points much slower and smoother, allows the images and shots to breathe. The whole pedagogical aspect, with its recurrent claims and quotations, is distilled through a great variety of styles and materials.

This is not a film shot and distributed clandestinely, like the Third Cinema defined by Solanas and Getino. Rather it can be understood in the lineage of the Soviet policy of the 1920s or the Cuban policy of the 1960s, namely where the State draws its legitimacy from its revolution, producing and distributing its own films of agitation and propaganda in solidarity with other revolutionary movements.”

Olivier Hadouchi1

William Klein: Anyway, once I got to do a couple films, I started getting involved in militant movies. After Mr. Freedom (1969), I was invited by the Algerians to do a film on the Pan-African Cultural Festival.

Jared Rapfogel: Why did they invite you, do you know?

Klein: Because my films were a big success in Algiers. Muhammad Ali (1969) stayed six months in three movie houses in Algiers, and they knew that I was kind of instrumental in a lot of the making of Far from Vietnam (1967). And they wanted to do a thing like Far from Vietnam, invite directors from all over the world, and make a film about the Pan-African Festival, where they invited all the African countries to come and show what their culture was about. I accepted right away, I thought it was exciting. What I didn’t know was that the Algerians were hated by the Cubans and by the Africans. Ousmane Sembene, for example, would not work with the Algerians; the Cubans said fuck the Algerians, because the Algerians were very rich, they had oil, they had gas. And the people in Poland, in Lodz, and all these people, they said, Fuck the Algerians!

Rapfogel: Were you the only one to materialize?

Klein: When the Algerians contacted me, they said, “Look, why don’t you do this film with a bunch of directors, and you can coordinate everything.” I said, “Why don’t the Algerians do it?” They said, “Well, we did a film on Algerian folklore last year, we shot like 100,000 feet of film, but we couldn’t make a film out of it, because all these guys were amateurs mostly, and we’re not going to be able do something that shows that we’re great producers, we want professionals.” So when I learned that we wouldn’t be getting these directors from Cuba and Africa and so on, I was stuck with it. So I had the idea of getting directors who were also cameramen – Pierre Lhomme, Yann Le Masson, Michel Brault from Canada, and guys like that, who are directors and cameramen. Since it wasn’t going to be a fiction film, and there were things going on all over Algiers night and day, we needed a lot of crews, and I thought the best thing would be to have people who can think for themselves, who know what to film and how to film it. So that’s what we did.

William Klein in conversation with Jared Rapfogel2

- 1Olivier Hadouchi, “‘African culture will be revolutionary or will not be’: William Klein’s Film of the First Pan‐African Festival of Algiers (1969),” Third Text, 25:1, 117-128. Translated by Cristina Johnston.

- 2Jared Rapfogel, “Mister Freedom: An Interview with William Klein,” Cineaste, September 22, 2008.