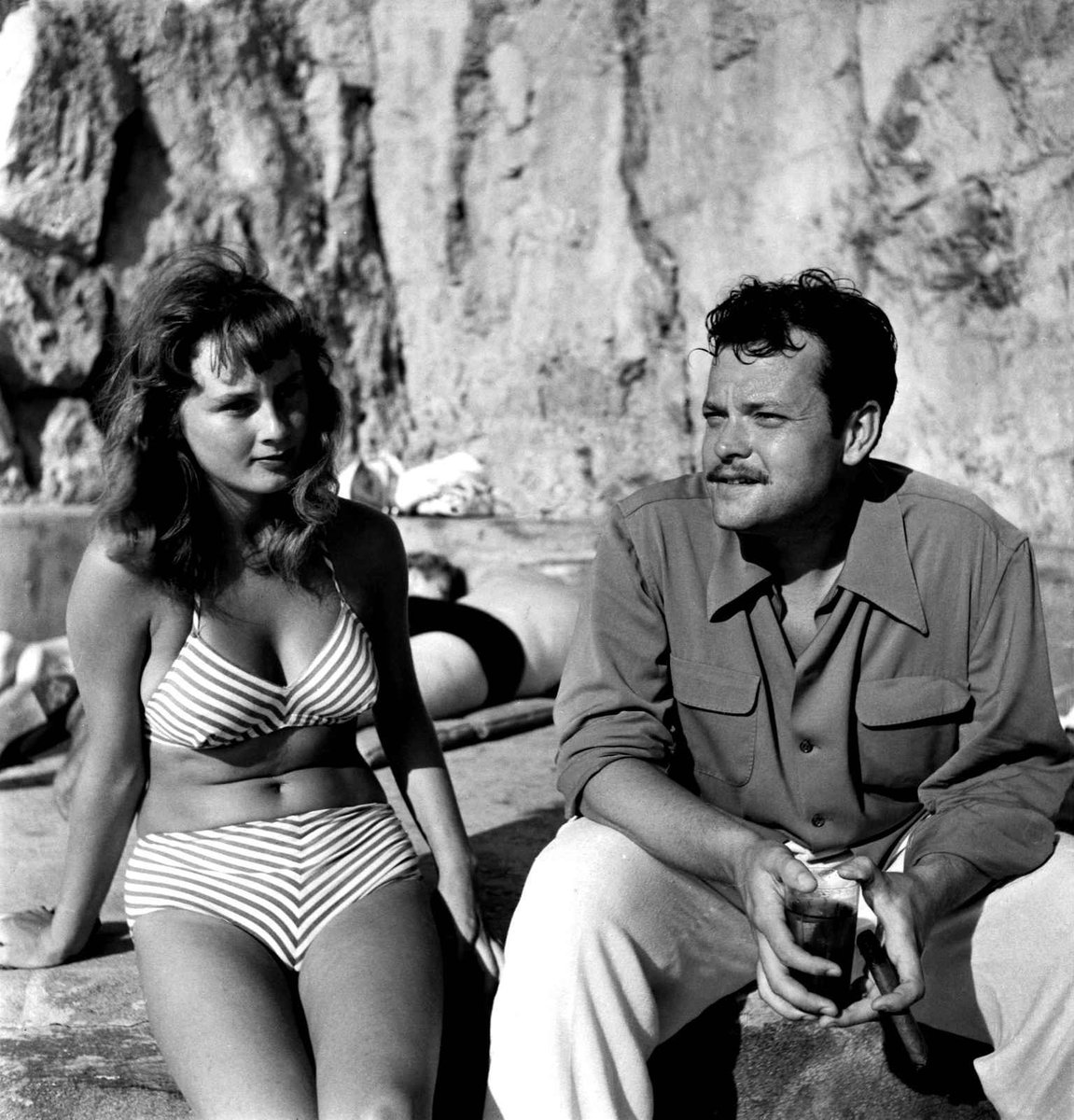

Cannes Festival 1947

A Psychoanalysis of the Beach

On the occasion of Éditions Macula’s recent edition of the collected works of André Bazin (1918-1958), Sabzian will publish nine texts written by the French film critic between 1947 and 1957, both in the original French version and the Dutch and English translations. Bazin is sometimes called “the inventor of film criticism”. Entire generations of film critics and filmmakers, especially those associated with the Nouvelle Vague, are indebted to his writings on film. Bazin wasn’t a critic in the classical sense. François Truffaut regarded him as an “écrivain de cinéma” [“cinema writer”], who sought to describe films rather than judge them. For Jean-Luc Godard, Bazin was a “filmmaker who did not make films but who made cinema by talking about it, like a pedlar”. In the preface to Bazin’sWhat Is Cinema?, Jean Renoir went one step further by describing Bazin as the one who “gave the patent or royalty to the cinema just as the poets of the past had crowned their kings”. Bazin began writing about film in 1943 and founded the legendary film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma in 1951, alongside Jacques Doniol-Valcroze and Joseph-Marie Lo Duca. He was known for his plea for realism as a crucial cinema operator. Film opens a “window on the world”, according to Bazin. His writings would also be important for the development of the auteur theory. He was an editor of Cahiers until his death.

The film critic. He tries in vain to brown on the beach of the Carlton. Around him, bronze athletes flirt nonchalantly with undeniably beautiful women. The kind of luxury beach beauty we only see in cinema. Several of them actually are movie stars, for that matter. Not the most beautiful ones, though. Mixed among them are unknown and nearly naked girls, whose function, of course, it is to be beautiful in the way one is beautiful on the screen. The density of physical beauty is infinitely higher here than it is on average across the French territory’s five hundred thousand square kilometres. Beauty is a luxury, like American cars and the palaces one sees on the Croisette. As such, it accompanies money everywhere. A place like Cannes is made of its climate, its landscape, its palaces, its festival, its American cars and these pretty women. So, the critic finds himself on the beach, among these men and half-naked women, heroes and goddesses, or Tarzan and pin-ups, if you like. He wasn’t even banned from penetrating the beach for his white skin. He tries hard to seem as nonchalantly indifferent as the brown-faced men are towards their companions, but, in all honesty, he doesn’t quite succeed. A lack of practice, no doubt. (It obviously is a party game they are well versed in.) Perhaps also the inferiority complex of not being Tarzan. The beach belongs to everyone, of course, and the sea too. But it would be pointless to deny the obvious: they are at home here. Not him. Luxury is a universe, an artificial earthly paradise one can try to enter by cheating (without paying, that is) because a free rider automatically suffers the punishment for his offence: he feels like an outsider. The sword of fire swirls around him. He is condemned to move among those admitted to paradise, who are like the recalcitrant dead in films that no longer use superimposition.1 The game is over. He is damned. Worse than Tantalus’s torture, as he is not even able to reach for his beach neighbour or try to start the hardwood-adorned Buick which is parked on the Croisette. That gesture would kill him. They tolerate him by ignoring him, provided he does not engage in these obscene incongruities. For him to play with the others, to be recognized as a living being by these dead ones, he would need to have been assigned some preliminary luxury function: producer, for example, movie star, multimillionaire, bestseller, or gym teacher.

At this point in his reflections, the critic realized that he was rather sad and was surprised that his cinema visits had not only not familiarized him with the spectacle of luxury, but also that this same cause had produced thoroughly opposite effects on the screen and in reality. Because the spectacle of his beach neighbour suited him perfectly, and the censorship of American films rarely leaves so much to see. What could he complain about? It was even more beautiful than in Technicolor. Come on, admit it. He was sad because all this was not his, would never be his. Because he did not dare to abuse his neighbour and steal the hardwood Buick. On second thought, he considered it a reprehensible but natural feeling, and he was even more surprised that it wasn’t shared by the hundreds of millions of poor souls to whom cinema feeds a similar spectacle on a weekly basis. Pedestrians and even bicyclists, the paunchy and the rickety, ugly women and old girls and quite simply the vast cohort of those who work for a living, all of those and many others give away their 100-franc notes every week to survey the aerodynamic cars and thighs they will forever be deprived of.

It was then that the critic realized that cinema was a dream. Not, as it is sometimes suggested, because of the illusory nature of the cinematographic image, not even because the spectators find themselves immersed in passive daydreaming, and even less so because it allows for the entire fantasy of dreams, but much more fundamentally in the strictly Freudian sense, because it is nothing but a “dramatization” of the realization of a desire.

At the cinema, no woman, no matter how beautiful, is forbidden since you are Clark Gable, Humphrey Bogart or Spencer Tracy, since you are free to be the king of DDT powder or a swimming champion. For those who do not participate in it, the reality of luxury naturally provokes the painful awareness of being banned. Its cinematographic dramatization, on the contrary, equals its realization and the euphoria of possession.

But it was time for the screening. The critic, his skin still white, only had time to get dressed and run off to the cinema.

- 1Bazin refers to an earlier text from 1945, “Vie et mort de la surimpression” [“The Life and Death of Superimposition”]. The “recalcitrant dead” here is a reference to Le défunt récalcitrant, the French title of Alexander Hall’s film Here Comes Mr. Jordan (1941).

This text was originally published as ‘Cannes-Festival 47. Psychanalyse de la plage’ in Esprit, 139 (November 1947) and recently in Hervé Joubert-Laurencin, ed., André Bazin. Écrits complets (Paris: Macula, 2018).

With thanks to Yan Le Borgne.

© Éditions Macula, 2018