Passage: Andrei Gorzo

My father was born in 1951 in recently turned-communist Romania. His parents welcomed him with a subscription to the comics magazine Vaillant, the organ of French communist youth culture. When I was born, in 1978, the magazine – reborn since 1969 as Pif Gadget – was becoming hard to find in Romania, as Ceaușescu was closing the country down. French communist culture was also declining – and Pif along with it. But back in the early ‘70s, it had been the most important European comics magazine targeted at children and young adults. Precisely between 1970 and 1973, they had published the great Hugo Pratt with his stories about Corto Maltese. My father hadn’t thrown away a single issue of Vaillant or Pif. His collection accompanied me during the 1980s and their dearth of youth culture. I started by skipping over Pratt’s pages, finding his drawings “ugly”. However, at some point I began to pore over them obsessively, trying to figure out why they disturbed me so much. I have no doubt that the process out of which I would emerge a film critic was put in motion at that time.

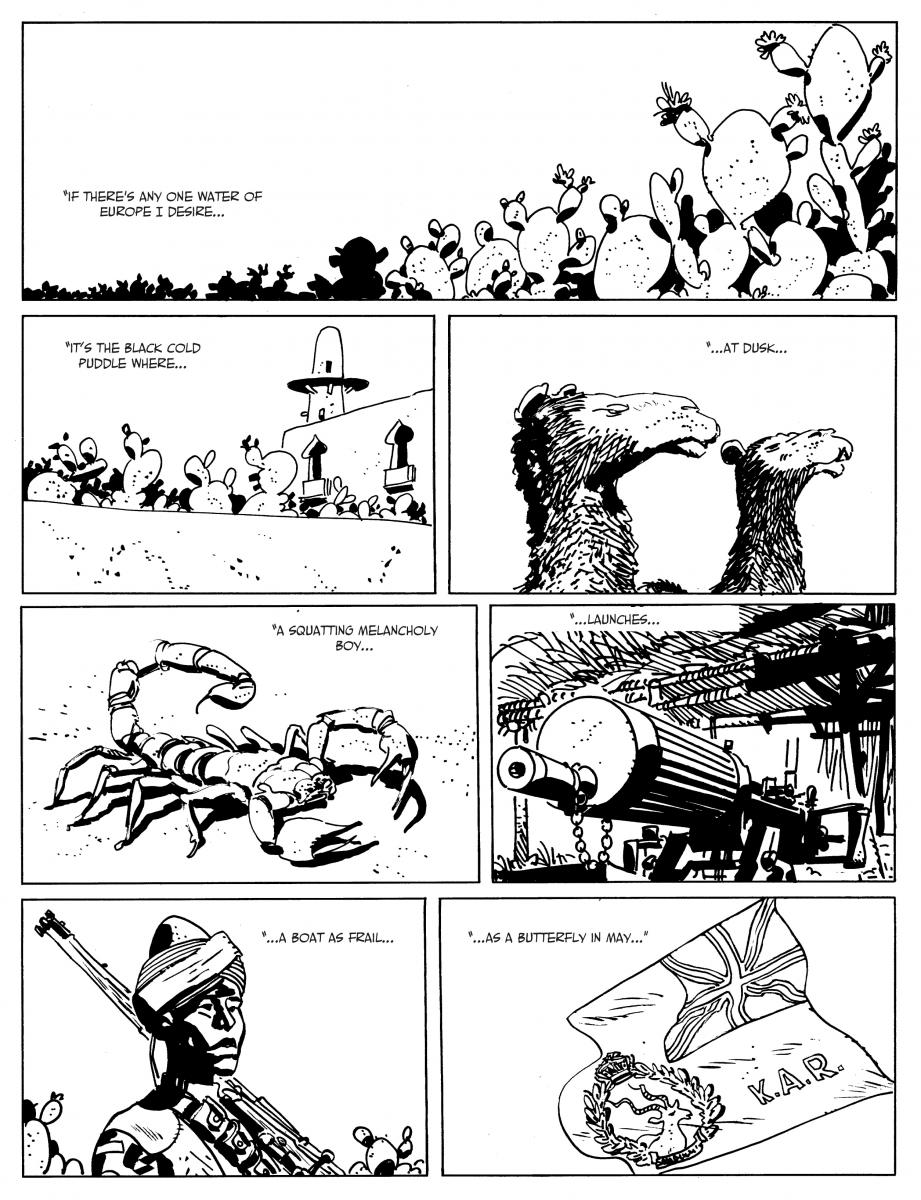

There was one passage that particularly stirred me: the opening two pages of a story called The Coup de Grace. The first page consisted of what I hadn’t yet learnt to recognize as a montage sequence – built on the principle of counterpoint between image and text.

On the image front, the reader was hit by a flurry of fragmentary views of a fort in British Somalia. On the front of words, where we would have expected to encounter a text that would enable us to fix those details in time and space (informing us that we were in 1918), Pratt hit us instead with bits of verse, which, by the end of the seven panels, added themselves into a stanza from Rimbaud’s The Drunken Boat. So, over that first page, Pratt’s mise-en-scène (as I hadn’t yet learnt to call it) accumulated collisions between the fragments of verse and the views over which they floated, thus doubling the reader’s feeling of dépaysement: the words conjuring up an imagery that was liquid, delicate and cool, while the drawings were of cactuses and stone, scorpions and machine guns, and that abundance of white space – the white of the scorching midday light. I stood examining each panel, savoring the mysterious echoes and vibrations of those collisions: the scorpion in the desert glare and Rimbaud’s “squatting melancholy boy”; Rimbaud’s butterfly and the flapping flag.

Then you turned the page.

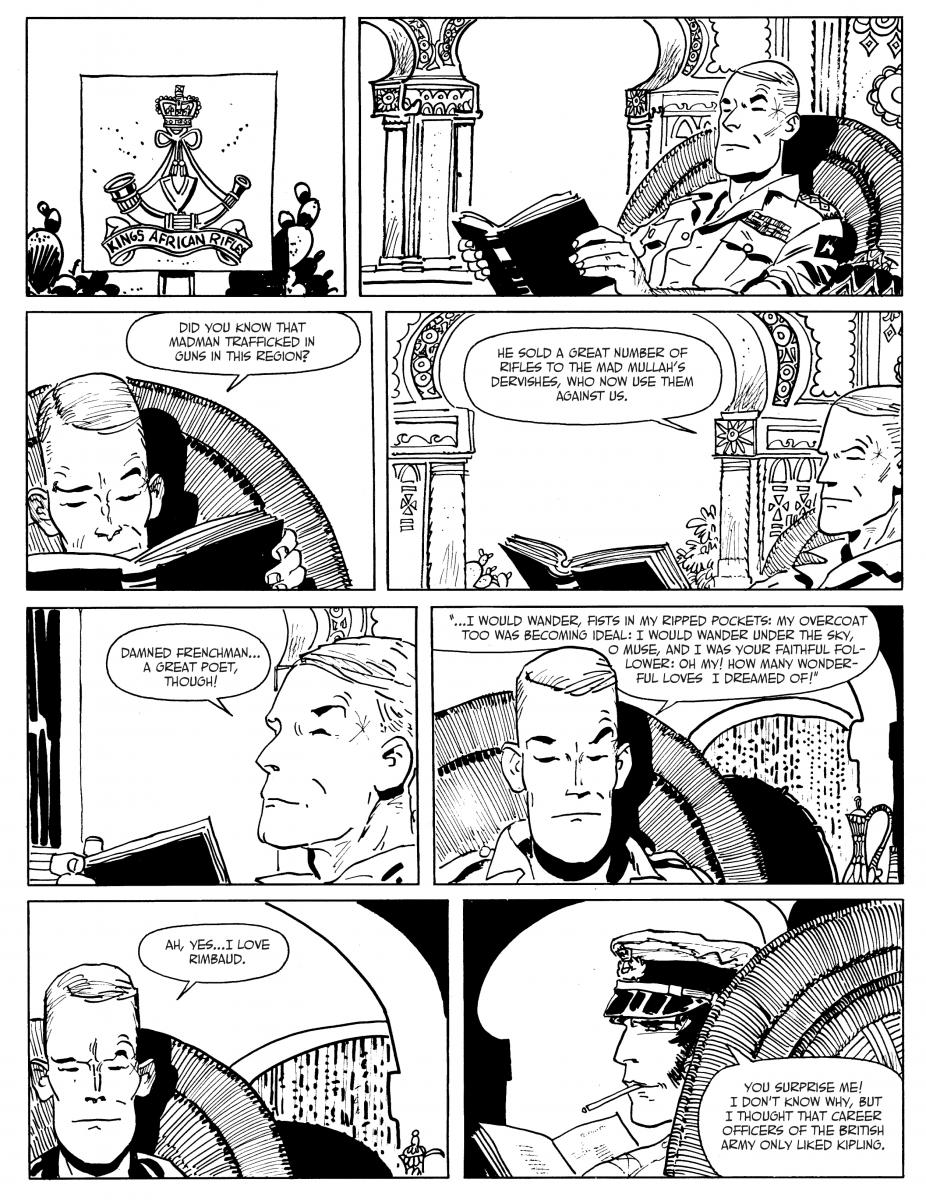

The top two panels were without text (except for the words “King’s African Rifles” on a blazon): an absence that we were meant to experience as silence – Pratt letting Rimbaud’s words fade away. Then, the British officer whom we had just laid eyes on finally connected the two worlds, asking: “Did you know that madman trafficked guns in the region?” Continuing in the next panel: “He sold a great number of rifles to the Mad Mullah’s dervishes, who now use them against us.” And in the next: “Damned Frenchman… A great poet, though!” His effusions went on for two more panels. In all, six panels consisting in close-ups of the captain plus balloons of fancy speech.

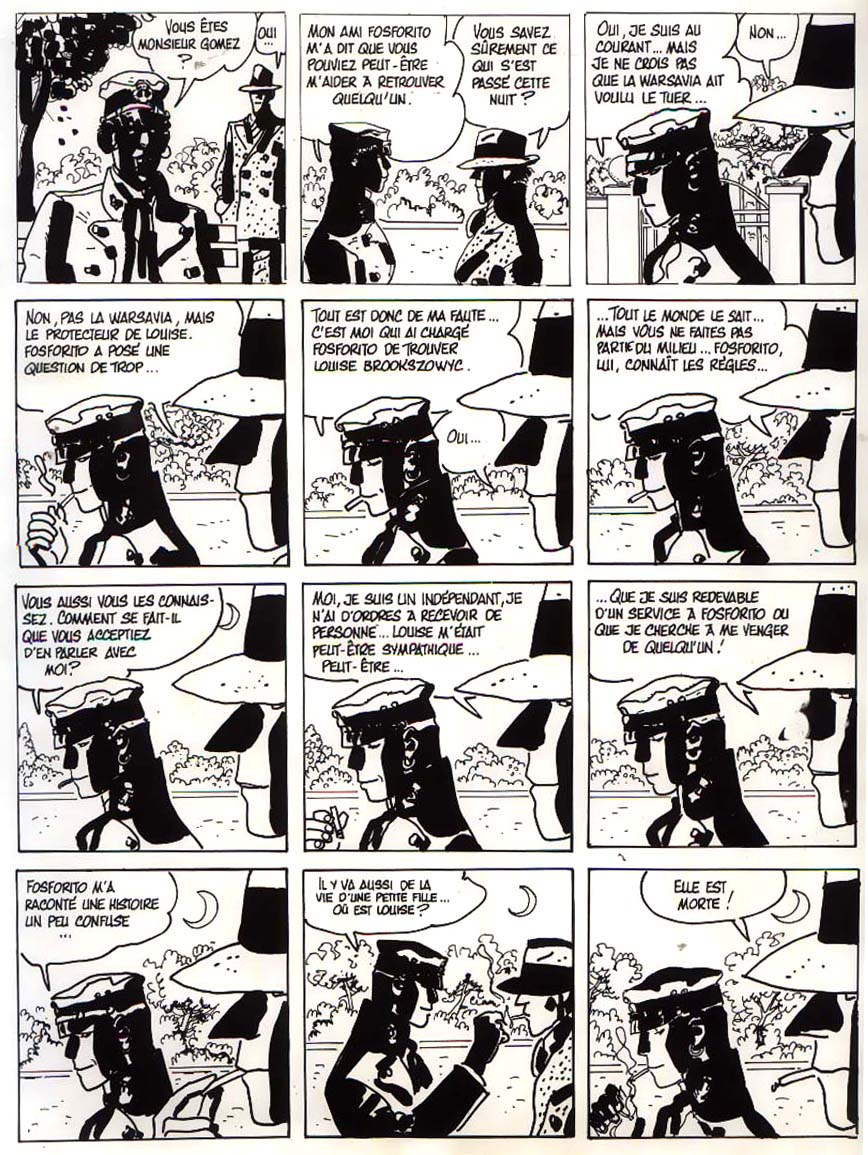

Now that looked dull – Pratt resorting to slightly different framings of one character who keeps discharging a heavy load of talk. That was long before I could understand that a resourceful artist like Pratt had more than one way of handling such a dialogue-heavy scene: in another Corto story, Tango, an exchange between two characters would be spread across ten almost identical panels, with both speakers inside the frame, the author inviting us not only to follow their conversation, but also to engage in a game of “spot the differences” – the handling of a cigarette, the expression of a mouth.

To put it in cinematic terms, the Pratt of Tango goes for the showy long take, while favoring a purely functional editing in The Coup de Grace. Of course, the cinematic analogy, as pertinent as it is – and Pratt always claimed that he educated his sense of the sequence at the cinema – only goes so far: in a beautiful book called Hugo Pratt, trait pour trait, Thierry Thomas writes that Pratt had been thrilled by Fellini’s observation that, “from the world of comics, cinema may borrow scripts, characters, stories, but not that ineffable and mysterious force of suggestion springing from its pinned-butterfly stillness”.

Back in 1987, when I was stuck on the second page of The Coup de Grace, I didn’t have the slightest grasp of such matters. But at a certain point I started to sense that there was something more than met the eye in that sequence, with its apparently bland functionality. By keeping the focus on the blabbing captain, Pratt was delaying the entrance of the captain’s interlocutor – Corto himself! – an entrance that Pratt had scheduled to occur in the very last panel of that second page. He didn’t need to make his découpage visually engaging in order to create tension; it was the teasing sense of the hero’s presence just outside the frame that electrified the accumulation of bland-in-themselves panels. Pratt was preparing for Corto a star entrance! I didn’t have a name for that yet. But I did sense – obscurely – that it was in some way about the cinema.

Images from Hugo Pratt, The Coup de Grace.

Thanks to Liri Chapelan for lending a hand with the English on an earlier version of this text.

In its section Passage, Sabzian invites film critics, authors, filmmakers and spectators to send a text or fragment on cinema that left a lasting impression.