Primary Material

A Conversation with Antoinetta Angelidi and Rea Walldén

Antoinetta Angelidi, now in her seventy-third year, has been among Greece’s pre-eminent avant-garde filmmakers since her breakthrough film Topos debuted at the 1985 Thessaloniki International Film Festival. Topos, Angeliidi’s second feature film after 1977’s Idées Fixes/Dies Irae, announced a singular new voice emerging from the ashes of the New Greek Cinema. Personal history and the history of image-making emerge as co-equal forces, in this film and all her films to come, less as distinct narrative or formal concerns and more as a fully conceived vision of the world. While her films are undeniably heady and reward multiple viewings, they are a product of both intellect and intuition. Her compositions are painterly and personal. From one sitting to another, The Hours: A Square Film (1995) can appear to be a nakedly autobiographical work or an art-historical visual essay on Balthus.

Angelidi’s filmography is sparse, but the work arrives on the screen concentrated like a diamond, enough to spawn multiple book-length studies in her native Greek. In five feature films across six decades, her commitment to a feminist artistic practice has remained unflagged. Central to much of Angelidi’s work is her concept of motherhood. Officially since 2001’s Thief or Reality, her daughter Rea Walldén has been a credited co-writer on each of Angelidi’s films. Their latest combined effort finds Walldén, a filmmaker and theorist in her own right, behind the director’s chair. Obsessive Hours at the Topos of Reality: Antoinetta Angelidi’s Confessions (Or an Essay on Her Gaze), which played at this year’s Thessaloniki Documentary Festival, is a retrospective look at Angelidi’s life and films, told in the form of an extended interview. Shot during the COVID-19 pandemic with limited means and a crew of only mother and daughter, Obsessive Hours can be deceptively simple. For much of the film, Angelidi speaks directly to the camera in response to her daughter’s questions. But the film is no less visually considered, no less complex in execution than Angelidi’s best work. Aside from the new light it casts on treasured works in her filmography – seen anew, literally, as the film was shot after Angelidi required two eye transplants – it stands on its own as a fascinating contribution to an ever-growing and shifting body of work.

Following the occasion of Obsessive Hours’ premiere at the Greek Film Archive in Athens, where I had the good fortune to meet Angelidi and Walldén, we arranged the following interview which took place at Cafe Rizzari in Athens’s Pangrati neighbourhood, with Walldén translating her mother’s Greek.

[Warning: the following text contains reference to sexual abuse].

Dylan Adamson: Could you tell me a little bit about your upbringing in Athens?

Antoinetta Angelidi: I have to begin by saying that I am a strange mix. My mother was from the Black Sea, from Batumi Georgia at the time of the USSR, the land of Medea. She came to Greece at the age of ten, but she kept her knowledge of the Russian language that she was initially taught in school. This was important in her life. She translated Russian literature and poetry into Greek. Her pen name was Milia Rozidi. She translated Chekhov, Anna Akhmatova, Marina Tsvetaeva, Osip Mandelstam and others. My father was born in Madagascar, he also came to Greece at the age of ten. His mother was Malagasi and French, and his father was Greek. My parents met at the Athens Polytechneio [Engineering University] during the German occupation. They were both studying chemical engineering – my mother was the second woman who graduated as a chemical engineer in Greece. She was also a feminist of the first wave. Equal pay for equal work was very important to her.

I was born in Athens, in the Kaisariani neighbourhood, on the 30th of April 1950. While still a newborn baby, we moved to the home of my father’s mother, Antoinetta, in the Pangrati neighbourhood. This home of my childhood was full of students at the Polytechneio: my two uncles and one of my aunts studied there, while my parents had just graduated from there and were already working. Two things characterized that group of people: the belief in the importance of mathematics and a strange belief in dreams. They felt that things that couldn’t be solved while awake, like mathematical problems, could be solved in dreams.

As a child, I was obsessed with two things. Firstly, for as long as I can remember, I’ve always drawn. And my family recognized not only that I was interested in drawing, but that my drawings were interesting. My aunt Iris, for example, took some of my paintings to Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas [a leading Greek cubist painter] who taught in the School of Architecture at the Polytechneio. And my mother worked with Gabriella Simossi [a Greek sculptor] at the General Chemical State Laboratory of Greece, who would give my paintings to her partner, Yannis Gaïtis [a Greek painter and sculptor]. He was interested in the naïveté of children’s drawings. Secondly, obsessively, I would walk to and fro. I didn’t have many toys, so I would walk to and fro, always creating a narrative in my head making characters out of the objects of the house – “Stovey,” “Cookerina,” “Stickie.”

My family was composed of intellectuals of the Left, so there was always an abundance of bookshelves. When my father returned from Paris, where he had done postgraduate study for a year, we left Athens and moved around Greece, living in different cities but mostly Thessaloniki and Patras, where he would be the technical director at different factories. And my mother would work in the different local departments of the State Laboratory.

When other people went to church on Sundays, my father loved to work by himself in the silence of the factory, and he would take me with him for an excursion. I loved it – walking up and down, narrating to myself in these huge empty factories. It was a very beautiful time. In a factory in Patras, I first saw the mounds of olive pits [that inspired the mounds in Topos]. I was in my first year at elementary school. They used the pits to make green soap – grinding them up into a grainy powder and making these mounds.

Then, at the age of ten, it happened. The rape by my violin teacher. For a time afterwards, I lost the ability to speak and understand. My father had the idea to use drawings to help me understand again. I’m very grateful to him for that. No one told him to do it, it was his idea. He would make very basic sketches, like storyboards, to explain a problem to me. Instead of using words, we would draw. Around the same time, they started taking me to painters’ workshops and buying art books for me. The guide of the British Museum, or the early Renaissance, these books became very important to me. I built preferences spanning from prehistoric cave drawings to modern art. I didn’t like the Impressionists at all, but I loved the Expressionists. It was around this time that I fell in love with De Chirico.

By secondary school, I could speak and understand again. I was lonely. Algebra made things easier for me, and my family was relieved to see that I was a good student. When I was around thirteen, my father and I moved back to Athens, a little before the rest of my family. This was 1963-64. In Athens in the 1960s, I experienced an explosion in creativity, painting many of the pieces that are shown in the new film [Obsessive Hours at the Topos of Reality]. This was a very interesting period for Greece. We call it the “lost spring,” after a novel [Stratis Tsirkas’s Hē chamenē anoixē, published in 1976, referring to the events of 1965]. We felt that there was a way towards modernization, towards democratization. Theatre experienced a renaissance at this time. I wouldn’t miss a performance of the Theatre of Koun [company of the famous Greek theatre director]. It was there where I first saw Marat/Sade. The woman who played Charlotte Corday, Maya Liberopoulou, I would later cast in Topos. It was a legendary period. People were doing seminars in aesthetics, philosophy, art, all open to the public. There were art exhibitions, contemporary music. In 1967, the Junta ended all of that.

I was working in the workshops of two quite famous painters, [Panos] Sarafianos and [Vaso] Katraki. Retrospectively, what I admired about my teachers is that they didn’t tell me what to do. They told me to be as faithful as I can be to myself, and I consider this the greatest gift. When I graduated high school, Sarafianos counselled me not to take the examinations for the Fine Arts School, because they were very conservative. Because of my skill in mathematics, I decided to enter the School of Architecture, at the Polytechneio. This was during the Junta and a lot of professors had lost their jobs because of their political views. In this desert, I found [Nikos] Engonopoulos [the Greek surrealist poet and painter], who was teaching painting at the school, and we became kind of sister souls.

I can see why you would be attracted to Engonopoulos’s work, as you liked De Chirico so much.

Rea Walldén: Correct me if I’m wrong, Antoinetta, but you don’t much like Engonopoulos’s paintings.

Angelidi: I became very good friends with Engonopoulos. I would come see him very early in the morning, and we would discuss much. He called me by my name, and everyone else by their surname. I told him that I don’t like his paintings very much, but I very much like his poetry. We would argue all the time. For example, I quite liked Max Ernst, and he would say, “What did he do? He cut up his grandmother’s magazines.” There were always these kinds of conflicts. But he taught me an approach to art that was very important. I speak about it in the new film. He told me about the monks who prepared themselves mentally and physically, fasting and praying, before making holy paintings. To face the process of creation. Even for the new film, without realizing it, I had started preparing to create a year and a half before. I lost twenty-seven kilograms.

Can you tell me a bit about your relation to cinema in these early years?

Well, Greece was already a peripheral country, and when we were moving around outside of Athens, this felt like the periphery of the periphery. So, I didn’t see a lot of cinema until I returned to Athens. I hadn’t seen any of the old Greek films. I do have one very strong early memory at the cinema, which must have occurred in Thessaloniki. I think it was Peter Pan. The image was a figure flying in complete darkness – this was my first image of what cinema could be.

Cinema really came to life for me when we returned to Athens in the 1960s. They would play films again and again, from 2:00 p.m. to midnight, and you could see them all with one ticket.

Were there many more cinemas in Athens at that time?

Many, many more. I used to watch everything. Not exactly everything. There would be three or four theatres showing Bergman, and they would be full of young people. Full! It was a short renaissance. But I wouldn’t see Hollywood films, not even film noirs. I would go to European films. I didn’t much like Godard, but Resnais – Hiroshima mon amour, written by Duras, and Last Year At Marienbad, written by Robbe-Grillet. I loved Resnais, and especially his treatment of time in Last Year. And it goes without saying that I loved the Russians and Mizoguchi.

Had you always imagined yourself becoming a filmmaker?

No. I was certain I would work with images, but I didn’t have cinema in mind at all until a specific moment while I was studying architecture. In 1972, I visited documenta 5 in Kassel, where I saw many contemporary art installations. And I had a dream of a painting that felt like a Magritte, except that it showed a tiny movement. I speak about this in the new film. It introduced for me, the sense of timing into an image – cinema. It was the sign that I would make films, but also a primary definition of the kind of films I would make. My kind of cinema is one of intense visuality. In Greek I call it “εικαστικός κινηματογράφος,” which translates to something like “visual cinema.”

For you, does this mean a particular relation to painting and composition?

This notion of the importance of image, cinema as a visual art, it sounds obvious, but it’s the relation between paintings, architecture as painting in space, and then cinema as painting in time. So, when I went to Paris, although I didn’t go there to study film, in a way, I already knew what kind of film I would do. So, when eventually I found the film school, I already had inside of me the principle of what I wanted to do.

Could you tell me about your time in Paris, and how it compared to your time in Athens? Were you exposed to different kinds of films there?

What I have to say is that when I was painting, I was thinking of cinema, and when I was making cinema, I was thinking of paintings. It’s not so much that I was watching many different films, but that Paris intensified my tendency to watch the films many times over. I found satisfaction in deepening my relation to a film – being attentive, looking, watching details. Not exactly analysing, just intensifying my attention watching the films. This eventually became my method for making films, where every detail takes part in the narration. You can take every sound, and watch the way that it develops through the film, or every costume. Every element develops in some way through the film and contributes to the narration. This, combined with Christian Metz’s teaching about the heterogeneity of the cinema led to my own approach.

I know that a lot of Greeks left Athens for Paris or London during the Junta. Could you tell me about what led to your decision to leave, and about your experience in Paris?

In Athens, before leaving for Paris, I was in the central bureau of Regas Feraios, one of the resistance groups. This group was the youth organization of KKE-Interior, which was the anti-Stalinist wing of the Greek Communist Party, after the party’s division in 1968. Regas Feraios’s leadership had previously been arrested, and some were sentenced to death. I joined the leadership closer to the end of the dictatorship. I was the only woman in the central bureau at the time, my code name was Athena. In August 1973, Stavros Tsakyrakis was arrested and tortured until he surrendered names – not mine. I am grateful to him. But I was advised to either leave Greece or go underground. And on the same day, when I went to the airport for my flight to Paris, the police raided my parents’ apartment. But I knew, and my parents knew from their participation in the resistance against the German occupation, not to hide anything in the home.

So, in August 1973, without even a suitcase, I left home. I arrived in Paris with nothing. For the first year I was there, I went to Vincennes, [Université] Paris VIII. After ’68 they had a revolutionary approach to education: psychoanalysis, semiotics, feminism. Jacques Lacan was there, all these people. Then, most important, I became part of second wave feminism: “the personal is political.” And then, out of the blue, I discovered IDHEC [Institut des hautes études cinématographiques], the film school. I decided to take the entrance examinations, although they were very difficult, and in spite of the fact that everyone around me was against it: my comrades in the party, my parents back home. Out of six hundred applicants, I was one of twenty admitted, despite not speaking very good French.

After May ’68, IDHEC almost collapsed and recreated itself, very much inspired by Cahiers du Cinéma. The exams were not conventional – no French language, no history, but compositional exercises instead, in image and sound. From six hundred of us, eighty advanced to the next stage, where we would sleep in beds in this auberge de jeunesse [youth hostel], like the army, for a whole week. For the sound compositions, they would play sounds with numbers attached, and ask us to recompose them into a score. So, we would say “Play the first part of sound three for this length, and then silence for that length, and then sound one for that length.” And twenty of us were admitted. It was ideal for me because they didn’t ask for any formal training. They asked for what I had: creative compositional abilities. My knowledge of painting and architecture helped me a lot. And Eisenstein’s concept of counterpoint inspired me – some of his theoretical work had been already translated in Greek.

So, in September 1974, I entered IDHEC. Several important figures were there, important in both my life and in film theory. One was Thierry Kuntzel. Kuntzel was further developing Christian Metz’s initial comparison between cinema and dreams. He spoke about the structural similarities between film and dreams. This is something that has been important for my own filmmaking. We had a very close relationship, a little bit like Engonopoulos and myself, but he unfortunately died very young from AIDS.

Another was Jean Thibaudeau, who was also an editor at Tel Quel. He specialized in Francis Ponge. If you watch the credits of Idées Fixes, he was consulted on the scenario.

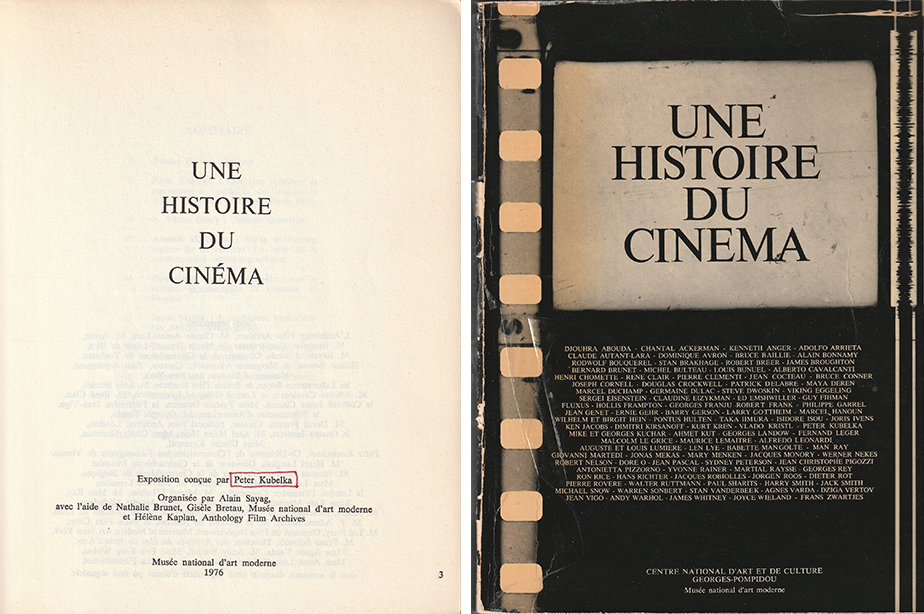

The final important figure at IDHEC was Noël Burch, who had unified and structured the knowledge around film editing. He advised all his students to go watch a program on the history of cinema, curated by Peter Kubelka at the Musée national d’Art modern. This program included the European avant-garde of the 1920s and ’30s, the expanded cinema and pure cinema of Europe, and the American underground. This was in 1976, and it was the first time that many of these films had ever been shown in France. Of all the films, Michael Snow’s inspired me the most.

Walldén: When La région centrale was screened, for all of Paris, there were only three or four people watching. One of them was Antoinetta who was pregnant with me.

Angelidi: Parallel to IDHEC, I was following the seminars of Christian Metz at the École Pratique, where he was teaching the semiotics of cinema. He drew attention to details. He would analyse a single film for an entire semester.

Related to this deep attention paid to single films, I wonder if you can tell me about your first experience with Murnau’s Faust.

From the moment we entered IDHEC, they threw us in the deep sea. On the first day, they taught us to deconstruct and reconstruct a 16 mm camera. And on the second day, after a very general explanation of how to use a Moviola, they gave each student one 35 mm film to view, and I got Faust. Only to view. To learn to cut, we were given other films. But Faust I was given to study, not to cut. On the Moviola, we would watch the films forwards and backwards, forwards and backwards. This being before computers, it was a rare opportunity to watch a film frame by frame this way, to see how different elements developed between still images.

My revelation happened at a moment right at the beginning of the film. It took me about a week to be certain that I had seen what I had seen. But what I understood was that the axis of the bell tower in the cathedral was on the same line as the body of Mephistopheles, from one frame to the next. I understood then, the way that editing and composition can work together. This was a visualization of the coexistence of the holy and the unholy, in these images. What once was surface now had an underlying structure, like architecture or painting. It was a sudden revelation: at last, I understood what cinema is.

At times your films seem oppositional to the dominant history of image-making. But there’s also a deep reverence for certain canonical figures like Murnau, Mizoguchi, Magritte etc. Could you talk about the tension there, if you feel there is some tension?

When I was painting, as in my films, I was always studying the entire history of art. I never localized to a specific period. I could choose to paint with a classical structure, or choose not to. Cinema for me was always my cinema. I was inspired by many things, and took things from many sources, but I would make my cinema. The question since May ’68 was about reinventing the cinema, building from scratch, no ancestors. We used the entirety of the past, not separating classics from others. Everything is primary material. One note is that I did not use Hollywood films for primary material at all. Or the old Greek cinema, Finos Films. In fact, the first Greek film that I saw was Angelopoulos’s Reconstruction in 1970.

There’s a question you ask yourself, in retrospect, in the new film: “What would we have to say that the avant-garde didn’t?” How do you feel you approached that question?

Like the rest of art history, the avant-garde was primary material on which to work. I never wanted to create something that would look like someone else’s work in particular. What I dreamed, when I dreamed of Magritte, was visual cinema. This did not exist at the time. Later, I found family resemblances with other filmmakers. I saw Greenaway in 1986, just after I had finished Topos, and I felt that we had things in common, but I didn’t know before. Later, I found Jarman. Much, much later, I found Bill Viola. If I must say, I think the four of us belong to a big family of visual cinema. But all this came later on. In Paris, in the 1970s, there was nothing like this. My particular approach to the visual cinema is characterized by each element contributing separately to the narration – the heterogenous function of the audiovisual medium.

Moving into your filmmaking career now, and given that the new film is a retrospective of your whole filmography, I’m wondering if you think of your oeuvre as more of a linear progression, or rather defined by continual reinvention and disruption? And either of you can feel free to answer this.

I’ve never asked myself the question, because every time I made a new film, I started from scratch. I forgot everything I knew, quite consciously. I never drew from my knowledge; I was always trying to reinvent the medium. At the same time, there is always experimentation in the heterogeneity of the medium, composing with the different lines of narration. But you can’t repeat anything. I think that although I may use a method, every work is a new start, a reinvention of the medium. This is one of the reasons that I take so long from one film to the next. If one sees a continuity in my work, they see that retrospectively, from far away. There are familial connections to be found, but every time I reinvent the medium.

Walldén: I believe that the answer is definitely both. It’s unquestionable for me that there is continuity in Antoinetta’s oeuvre. But this is because, to a certain degree, it’s the same person creating and you can see that person expressing herself and evolving. For example, what she lately describes as her methodology, it is not something that she conceived from the beginning consciously as such. When she started teaching it, she started seeing it as a methodology. However, the method exists in a way since the beginning. You can find several characteristics that traverse her filmography, no matter how different each film is. You can feel the relation to body, to composition, the use of heterogeneity, the dream mechanism, the uncanny. Yes, there are also great breaks. I think that the most obvious break is between Idées Fixes and the rest. The shorts that she made before Idées Fixes are lost. But I can see that from Topos onwards, appears this darkness, this deep black background, which I consider very characteristic of all her films after Idées Fixes. And also, there is a, let’s say, more mature strangeness. It’s a combination of the uncanny and distanciation. In Idées Fixes this distanciation has more to do with Eisenstein’s concept of counterpoint. In the rest of the films, it becomes more complicated. There are more difficult tensions and, at the same time, a kind of magical feeling. So, I think that with Topos, her style matures toward something more particularly hers. It’s true that she takes a long time between films, but each film is a condensation of so many different things.

I’m thinking of The Hours – probably your most direct and easily legible film in terms of how biography relates to your filmography. How does your life affect your filmmaking and vice versa?

Angelidi: The kind of cinema I’m trying to do is a composition of traces, from the history of culture as collective memory, but mainly as collective unconscious. We have traces of the history of art and then personal experiences. These are the raw materials. I distance myself from reality in order to come closer to the Real, with a capital R. The Real is non representable.

In The Hours, I used very specific incidents exactly as they were. But the composition I made concerns everyone. I’m using elements of biography, creating a composition, balancing different tensions. Things that might have been unimportant become important, so that the final synthesis doesn’t look at all like my personal life. A film character may be a synthesis – a composition of different real people. The elements introduced from different parts of my biography may be introduced in the same shot, for example. So, the raw material is my life, but the composition is not. Even specific images, specific scenes present my memories through paintings by other painters.

Walldén: It is as if her memory wears the clothes of a painting. She did have a nanny that was watching her behind the door, but in order to create this scene she used that painting by Balthus, where there is a character who is opening the curtains of a window. So, the curtain and the movement are from Balthus, the dress that the nanny is wearing is from Max Ernst, but the dramaturgical part is from her memory. It is a collage, but a collage happening at different levels. One character wears the dress in black, and the same actress wears the exact same dress in white. The same actress plays three characters. Different references and different images merge with one another, so nothing – painting, memory, nothing – is simply reproduced. Every element tells its own story. You can follow the story of the dress, for example, for the entire film.

My favourite image in your work, that’s changed and adapted throughout the film, are those wonderful mounds in Topos. I know it was shot in the Gazi gasworks. Could you tell me a little bit about what they evoked for you when you first saw them? And how do they factor into the film’s symbolic landscape?

Angelidi: The mounds were not in the gasworks in Athens. I had initially seen them in the factory from my childhood. So, they were a recreation in that new environment. When I first entered the Gazi gasworks, I was moved in a very physical way. I felt as if my legs could not hold me, my knees could not hold me. I kneeled there and put my head on the ground. I felt that the factory was a holy place. I reconnected to my childhood, to my memories of childhood walks with my father in the empty factories. For me, the game that I was to play in cinema was a continuation of the games I played as a child in those factories. And I felt the labour of everyone who had worked there was condensed in the matter around me. This was the year after the factory had closed. Thankfully, it was before it was destroyed. Later, it would become a cultural centre, gentrified; they took out the machines, made it very clean, and it’s now very difficult to feel it there.

When I first entered, it felt like a landscape out of Dante’s hell. This is what led me to open Topos with those verses from Dante, when he meets Virgil for the first time. If you remember the verse, he says, “In the middle of my life I found myself in a dark forest.” Dante was thirty-five years old at the time, and I was thirty-five years old when I made Topos. I kept the verses in Italian because I preferred the sound, the music of the words.

Rea, how has your understanding of Antoinetta’s work affected your own perception of motherhood or daughterhood, or of understanding images in your own career?

Walldén: You see, it’s not really the films. The films are part of me, in a way in which I’m not exactly a spectator, or not just a spectator, because I have lived them. Nowadays, in my academic career, I am, let’s say, a specialist in her films. So, I can have some objective distance to discuss them. But that’s not really the way they’ve affected me. I’m more affected by the process of making. I remember the shooting of Topos as a magical thing.

You would come to the set.

Of course, yes. And it was something incredible. I entered this game of the crew and the shooting, it was secret, but also very fun, very intense, very wonderful. And then the film is something else, you realize it’s a different thing. A lot of things that I’ve since theorized, I first lived through. There’s a huge distance between the film and the pre-filmic event.

At the same time, her creation was also our everyday life. We lived in a house where the process of making the films was what mom did, which at a certain age is what the world is. She speaks about how the Greek Film Centre did not accept a lot of her films – those were huge events for us. Discussing and writing and then proposing the film, and seeing it get rejected.

Angelidi: [Interjects in Greek]

Walldén: I didn’t know that at the time. She explained how we lived for three years with the prize that she won for Topos. But I had no idea how on earth all this marvel related to the fact that we stayed alive. There were the actors rehearsing in our home, people coming and going. She made the films and we stayed alive. Even in the most difficult times, in the ’90s, there were interesting people coming in and going, interesting things happening. They did rehearsals in our home. We had this huge library. I read Dostoyevsky, the most inappropriate things, when I was ten years old. It was an unconventional way of being, we made our own rules. I’m speaking to you more about my experiences of life rather than her films, but this is the way that the films affected me. When I approached the films later, as an adult, as a spectator and a theorist, when I became her collaborator after high school, I read her entire library of scripts, and that’s when I entered the world of cinema as a conscious participant.

Now, about motherhood, daughterhood. I have always admired her as a woman, in a society that was not accepting of a woman like her. And now I define myself, as a creative woman, not being less-than. She was an unconventional and unconditional mother. She left her marriage but she didn’t leave us. A single mother, in a society where divorce was not completely accepted. It started almost naturally, us working together. The films were the way we lived. But then they became a conscious way of understanding myself. A statement of existence. We made the choice to make films together, being mother and daughter, and to be kind, to be loving, and not to be adversaries. Because the dominant narrative that is told about mother and daughter is conflict, aggression, and competition, in a way that is absent from the narrative of father and son. Son takes the place of father, but why does the story of mothers and daughters in patriarchal society seem to be a story of annihilation? It does not go without saying, the fact that you can have a friendly relationship. She’s not making herself less by being mother, and I don’t make myself less by being daughter. We can be equivalent in our collaboration, and yet mother and daughter. I mean, she’s my mother, she’s my teacher, I adore her.

I wrote this text for 121280 Ritual (2008), a poem of adoration about how, for a child, the mother is the universe. And now I’m an adult, and it’s still inside me, the person that experienced her as the universe, but she’s also another adult, a separate person, a person that I can criticize, I can be different from, I can disagree with, and we can work together. The only way to work together is if you are separate, if you’re not the same person. In this view, as a theorist, I’ve read her films as feminist manifestos, and I believe that they are so. For example, I believe Topos is the story of a daughter searching within the tradition of mothers.

I’ve read you on that, it’s very insightful.1 What was the genesis for the new film?

Angelidi: The first lockdown, from Easter to summer 2020, fell exactly between the two transplant operations for my eyes. The first happened in October 2019, and the second in October 2020. Something very strange happened to me. I felt, inside myself, a strange tranquillity, a quietness. It may have had something to do with the gratitude I felt to the dead donors of the transplants. But simultaneously, I started to perceive everyday reality, to concretely realize the complexity of time, which up to that moment I had only been able to perceive through cinema. I would leave the building for short walks around the block, and nothing seemed the same from one day to the next. I realized that every small detail was important. I had an ever-increasing feeling that our planet is alive, and we are only visitors.

Alongside this, since Thief or Reality, I had been trying to find a single composition of words to combine the titles of my four feature-length films. It was a game I was playing, recomposing the different words. Out of the blue, amidst this feeling of quietness, and seeing the world differently every time I stepped outside, I found it: Obsessive Hours at the Topos of Reality. It’s the title of the new film.

Walldén: When Antoinetta first told me about this new film, I had assumed it would be a version of some previous discussions of ours, not this confession. And I was a little bit terrified. It was a short production, not much money, and so much that had to be done. But she had a very strong desire to do it, to speak, to do it now, to catch it before it leaves. She was in a very tranquil place at this moment – I was not at all. It was very intuitive. Antoinetta had prepared herself mentally and physically. I knew what to do: I had to give her space to do what she wanted to do. We asked friends about some technical aspects and shot with no script. She knew there were themes she wanted to speak about, but the conversation was completely spontaneous. It was like a trance, but a conscious trance, as she likes to say. We didn’t lose ourselves.

The film is improvised but very intentionally structured. We started shooting after the sun went down and went on until we couldn’t anymore. We wanted her to be emerging out of darkness, as in her films. We did several other takes that weren’t used, but the ones we used were all shot close to each other. But we found, editing, that there were these repetitions, not pre-scheduled. And it was fascinating, saying the same thing the first time she would have her arms open, and then in the repetition they would be closed. The final work is very structured. Why certain things are black and white, why certain spaces appear only in the final quarter of the film, the background noise, everything is very tightly structured, but only retrospectively, in the editing.

It’s interesting that this change to speaking not through images but through words seems to coincide with a greater appreciation, during quarantine, of the outside visual world. The film discursively relates to so much of Antoinetta’s body of work. Edward Said has this concept of Late Style:

“Each of us can supply evidence of late works which crown a lifetime of aesthetic endeavour. Rembrandt and Matisse, Bach and Wagner. But what of artistic lateness not as harmony and resolution, but as intransigence, difficulty and contradiction? What if age and ill health don’t produce serenity at all? This is the case with Ibsen, whose final works, especially When We Dead Awaken, tear apart his career and reopen questions that are supposed to have been resolved before such works are written. Far from resolution, Ibsen’s last plays suggest an angry and disturbed artist who uses drama as an occasion to stir up more anxiety, tamper irrevocably with the possibility of closure, leave the audience more perplexed and unsettled than before. It is this second type of lateness that I find deeply interesting: it is a sort of deliberately unproductive productiveness, a going against.”

How do you respond to this characterization of an artist’s final act? Do you see yourself in this, or the opposite?

Angelidi: This inner silence, the inner tranquillity, which went together with the feeling that I have different people inside of me, starting with the realization that I have with me two different dead people in my eyes, I felt this consciously. It might have existed before but not consciously. We call it DNA. We carry inside us the entirety of dead humanity, and therefore we are responsible for our relation to the planet. The strange thing is that this inner understanding makes me angrier, it makes me rage against the blindness that I can see. Inner clarity does not lead to a kind of outside silence, being in harmony with everything. When you have inner clarity, you do not become quiet or tranquil or peaceful. What we may describe as Zen, I would say Nirvana rather, this inner quietness does not mean that we become pathetic.

The point is, when you become calm and clear inside, it doesn’t mean that you accept the outside world as it is. It may lead, as it has in my case, to becoming more energetic, a kind of an activation. It is not necessarily this perception of the wisdom of age that accepts everything and finds that everything is right. The wisdom of age may be a wisdom of revolt.

That everything is wrong.

That you need to change things. [Laughs] I didn’t say that everything is wrong. You see clearly that blindness, even in political terms, is a very complicated thing. There is not a one-dimensional way of how one can resist. Clarity may lead to a more complicated view of reality. Inner peace goes along with the clarity of seeing the world self-destructing. So, you have to be decisive. This clarity of seeing the world or humanity destroying itself must lead to decisiveness of action.

Are there plans to shoot another film, or should this film be considered a final statement?

To close the interview, yes, I definitely would like to do another film, if I live long enough.

- 1Rea Walldén, “Weird Mothers: The Feminist Uncanniness of Antoinetta Angelidi’s Topos,” in ReFocus: The Films of Antoinetta Angelidi, ed. Penny Bouska and Sotiris Petridis (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2023), 15-44.

Images (1), (8) & (12) from Topos (Anoinetta Angelidi, 1985)

Image (2) Mystery and Melancholy of a Street (Giorgio de Chirico, 1914)

Image (3) Civil War (Nikos Engonopoulos, 1948)

Images (4) & (5) Une Histoire du cinéma: Exposition (Peter Kubelka, 1976)

Images (6) & (7) Faust (Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, 1926)

Image (9) from Caravaggio (Derek Jarman, 1986)

Image (10) La chambre (Balthus, 1952-54)

Images (11) & (13) The Hours: A Square Film (Anoinetta Angelidi, 1995)