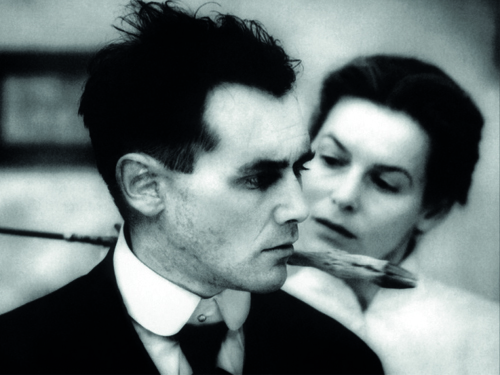

Jakob enrols into the Benjamenta Institute, a dilapidated boarding school for the training of servants. He then tries to unravel the hidden mysteries of the school, his fellow pupils, and Frau and Herr Benjamenta, the siblings who run it.

“One will learn very little here… none of us will amount to much.”

Jakob von Gunten

“‘Ik zal braaf zijn, ik beloof het u. Ik zal al uw bevelen gewillig opvolgen. U zult zich nooit, nooit over mijn gedrag te beklagen hebben.’ - Juffrouw Benjamenta vroeg: ‘Is dat zeker? Zal ik me nooit te beklagen hebben?’ - ‘Neen, zeker niet, juffrouw,’ antwoordde ik. Ze wisselde een veelzeggende blik met haar broer, meneer de directeur, en zei tegen mij: ‘Sta vóór alles eerst van de grond op. Foei. Wat een gevlei en gefleem. En kom dan mee. Wat mij betreft kan je ook ergens anders slapen.’ Ze bracht me naar de kamer, die ik nu bewoon, liet hem me zien en vroeg: ‘Bevalt deze kamer je?’ - Ik was zo brutaal om te zeggen: ‘Hij is eng. Thuis waren er gordijnen voor de ramen. En de zon scheen daar in de vertrekken. Hier is alleen een smal ledikant en een wasstel. Thuis waren er volledig gemeubileerde kamers. Maar wordt u niet boos, juffrouw Benjamenta. Het bevalt me, en ik dank u.”

Robert Walser1

“Perhaps less fearful than Kafka, but nonetheless sharing characteristics with his cosmogony, Robert Walser (1878-1956) was a Swiss writer who wrote prolifically for newspapers and journals and whose novels and short stories inspired a number of the Quays’ films (The comb [From the Museums of Sleep] and Institute Benjamenta). Fragments and themes from Walser’s writings are strewn throughout their opus. It is invaluable to consider unique aspects of Walser’s writing style as the second author in Quay triumvirate of Kafka, Walser and Schulz, and to see how these three authors’ writings speak to each other. In an afterword to Institute Benjamenta, the English translation of Walser’s Jakob von Gunten (1909) and the textual inspiration for the Quays’ Institute Benjamenta, Christopher Middleton (whose writing on Walser was an entry point for the Quays) comments, “In reality, the book is more like a capriccio for a harp, flute, trombone and drums.” The musicality of Walser’s writing has been repeatedly emphasized, and it is full of musical comparisons and metaphors. Peter Hamm provides some of the most fitting descriptions: “The stars and the sun sing, a room possesses a precious tone, a girl’s gentleness is like a stream of notes. He compared nights to black sounds, someone enjoys his slowness like a melody or a city affects him like a symphony. In his essays, novels and microgrammes, the compositions and dialogues are reminiscent of musical inspirations, a quality that Walser himself often mentioned.”

Suzanne Buchan2

“Thyrza Nichols Goodeve: “A beautiful quotation opens Institute Benjamenta:

Who dares it – has no courage

To whom it is missing – feels well

Who owns it – is bitterly poor

Who is successful – is damaged

Who gives it – is as hard as stone

Who loves it – stays alone

What is “it”?

The Brothers Quay: “It” is the riddle, the enigma. The quote isn’t from Robert Walser’s novella but from an anonymous folktale, a conundrum, that Carl Orff set to music and that we’ve had a cassette of for 19 years. Our initial ravishment was the music; we’d never had the text translated. Yet it utterly intrigued us and so we began corresponding with the Orff foundation to trace the text’s origin – which of course remains unsolved.”

Thyrza Nichols Goodeve in conversation with Stephen and Timothy Quay3

“In the film’s opening close-up shot we see the first pair joined together: two forks point upward, holding a fine circle-shaped wire. (...)

The answer to the riddle is “nothing,” which is not spoken, but announced visually as the animated forks withdraw, leaving a glimmering zero. With this zero and its numerous iterations the Quays make concrete and visible Jakob’s metaphor for self-reduction and subservience. “In later life I shall be a charming, utterly spherical zero”, he writes near the end of his first diary entry. (...)

To this end Jakob claims to have become “a mystery” to himself. The German here is “Rätsel” or riddle. If Jakob’s path to becoming a zero involves self-reduction, making oneself small and insignificant, then this same attempted self-erasure has a mystical flipside. As I have written elsewhere, the “mystery” or “riddle” of the book (which is echoed by the Quays in Carl Orff’s riddle) suggests that nothing/zero represents a state of transcendence as well as “a loophole” that allows Jakob to attain that state. For if “attain[ing] a kind of godlike immediacy of knowledge… only coincides with the absence of knowing altogether”, then the zero appropriately stands for both absence and abundance. Jakob’s formulation “kugelrunde Null” (in Middleton’s translation, “perfectly spherical zero”) expresses this paradox with an oxymoronic metaphor that borrows the adjective that is used in German to describe a stuffed belly (kugelrund) to emphasize that this zero represents not emptiness, but fullness.”

Samuel Frederick4

- 1Robert Walser, Jakob von Gunten, een dagboek, (Amsterdam: Arbeiderspers, 1981), 13.

- 2Suzanne Buchan, The Quay Brothers, Into a metaphysical Playroom, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 58.

- 3Thyrza Nichols Goodeve, “Dream Team: The Brothers Quay”, Spike Magazine, September 2011.

- 4Samuel Frederick, “An Antlered Adaptation: Stag Iconography and Animal-Human Hybridity in the Quay Brothers’ Institute Benjamenta”, Academia, 7.