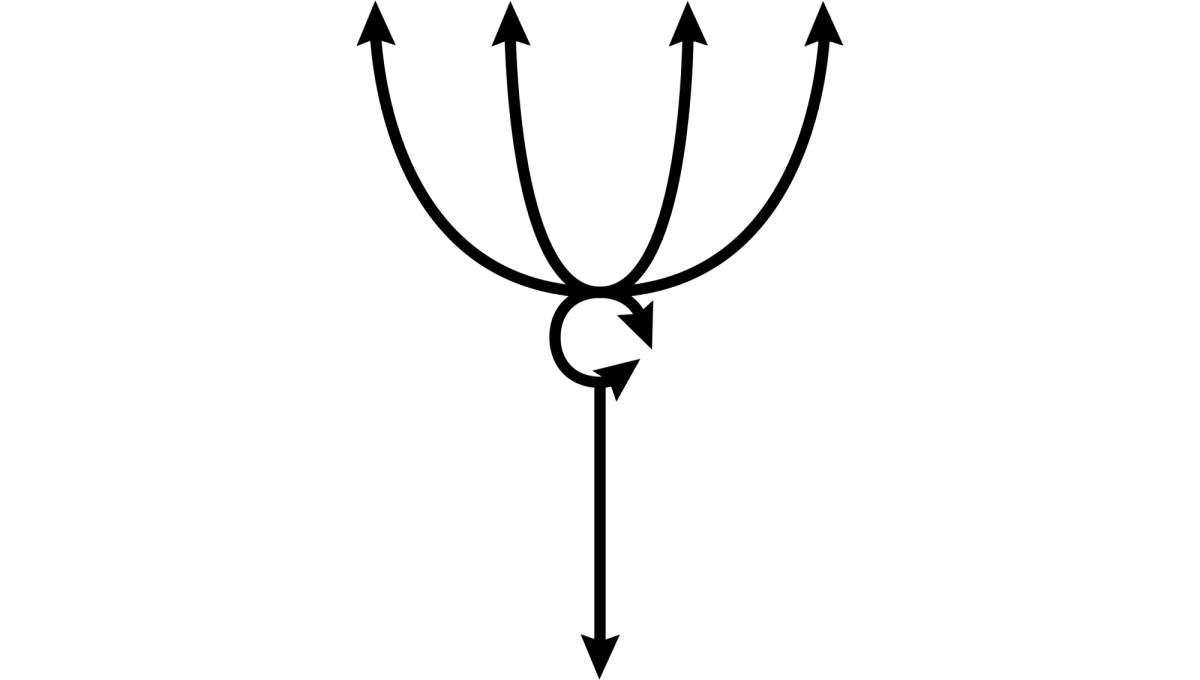

Shot over ten years and in almost as many countries, La Flor pays tribute to the history of cinema via six episodes bound together by the performances of the same four actresses. The first four parts of the film – represented by the petals of the flower that the director draws in the introduction (see below) – have beginnings but no endings; the fifth episode (the semi-circle, the core of the flower’s structure) tells a complete story; while the sixth and final part of the film lacks a proper beginning but does have an ending. Each of the six episodes of La Flor takes off from a genre. The first episode could be regarded as a B movie, the kind that Americans used to shoot with their eyes closed and now just can’t make anymore. The second episode is a sort of musical with a touch of mystery. The third episode is a spy movie. The fourth episode is difficult to describe. The fifth one is inspired by an old French film. The last one is about some captive women in the 19th century who return from the desert, from the Indians, after many years. And then there are 40 minutes of credits.

“La Flor’s arrival will require another rethinking of exhibition. La Flor challenges how festivals and exhibitors work and questions their influence in contemporary cinema. First, through the obvious: its running time. The film is hard to fit into schedules. It is intended to be screened in parts: generally in three, but it has also been shown in five and eight. This requires taking time slots from other selections, messing up the most basic festival economy of how much a ticket costs per movie. Secondly, there is no Vimeo link. For its consideration, a screening has to be organized. The film’s power comes from the experience it proposes. Its nature cannot be separated out. La Flor requires the immersion enabled by the ritual of theatrical screening. This sort of commitment is not part of the festival industry’s logic of consumption. At least once and for 14 hours, La Flor disrupts the exhibition system; La Flor only exists if it can be screened.”

Matías Piñeiro1

“Closer in spirit are the films of Jacques Rivette, where the narrative games on screen function as a spell cast on characters and viewers alike. Indeed Rivette’s description of the role of fiction in his own magnum opus, Out 1 (1971) – as a force that ‘swallows everything up’ – applies here. (...) [Llinás] has described La Flor as a fictional adaptation of Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinéma and the impulse is comparably encyclopedic, the tone similarly elegiac and defiant. (...) Romantic to the core, La Flor is a declaration of faith in the medium, a showcase of its infinite flexibility. One of Bresson’s most piercing statements from late in his life comes to mind: ‘The cinema is immense. We haven’t done a thing.’”

Dennis Lim2

“La Flor admits the real as raw material, and is all the more moving because of it. The film vibrates with a life force that feeds off the urgency to create. It’s not so much a documentary of its own making, as Rivette famously said about all films, but an ode to the world in which it was created, and those who propelled it into being.”

Andréa Picard3

“If the history of film were based, like ancient mythology, on legends and fables, then no one could disregard the end of Stromboli, terra di Dio, the film that Rossellini premiered at Cannes in 1950. (...) At the end, the woman decides to flee and, in a quasi-mystical act, ascends the erupting volcano. The final image is of the woman, almost now a saint, looking out on this boundless and terrible panorama. So why do we think this ending is essential? Well, because that woman, facing death, dazzled by the spine-chilling beauty of that devastated land, is Ingrid Bergman, the most important actress in the world, the same who years earlier had stunned Hitchcock and Bogart, and had swanned like a queen through the palaces of the world. The same woman who, just months before becoming that anonymous peasant, had been Joan of Arc. (...) The filming of Stromboli was the first time that the earlier career of an actor turned a fictional scene into something else.

The aim of the project titled La Flor is similar to that of Stromboli, but with an added ingredient. The film does not set out to use an actress’s prior work to bring a particular emotion to a series of images. Instead, La Flor aspires to construct, to constitute this experience. The experience is the very film itself. Viewers see various actresses’ careers unfolding before their eyes, as part of the same film. The idea is that one film should be a series of films, an era in the life of four people, and that cinema should be able to show this passing of time, this learning, this process. That from the different inventions and fantasies that the avatars of the project gradually contribute, one can see eventually the true face of the four women, shining brightly through the fog of fiction.”

Mariano Llinás4

Jordan Cronk: Take us back ten years. You finish Historias extraordinarias (2008)– what’s next in your mind? I can’t imagine it’s a 14-hour film.

Mariano Llinás: This was still the beginning of the new century, and fiction was in trouble – it was endangered. During that time everyone was talking about the boundaries between documentary and fiction, and people still are. But nobody was thinking about or finding the pleasure in fiction, nor in the real. Everyone would say, ‘I’m not interested in telling regular or traditional stories,’ which is an idea I believe in, because I do think storytelling is plagued. But the cure for storytelling wasn’t the one that people were trying, which was a… I don’t want to say slow, but a dispassionate form of cinema lacking in intensity. I was thinking that, if used correctly, nothing can be as emotional as fiction. (...) [I] thought that leaving fiction out of the cinema was not the right way to go against the obligations of storytelling. I was thinking that maybe fiction and storytelling are not the same things, and you can make strong, rich, extreme fantasies without falling into cheap storytelling, or toward moralizing or wherever storytelling often takes us.

Mariano Llinás in conversation with Jordan Cronk5

« Cette saturation extrême d'histoires, et d'histoires à l'intérieur des histoires, est donc bien plus que le portrait de quatre femmes. C'est surtout le récit d'un duel (qui est aussi une relation d'amour) entre une troupe théâtrale et un cinéaste, dont le résultat est l'une des propositions de fiction les plus radicales de l'histoire du cinéma. (...) À revenir, en quelque sorte, aux frères Lumière. Ce qui imprègne La Flor d'un sentiment de film total, qui se questionne en permanence, dans son rapport à la fiction. (...) Ce qui reste à la fin de La Flor ce sont des questions essentielles que plus grand monde ne se pose (même plus Godard, ou bien il le fait autrement). (...) Voilà ce qui émerge surtout du film, comme de tous ceux d'El Pampero, avec une force renouvelée : le réel, la terre, le politique. »

Fernando Ganzo6

- 1Matías Piñeiro, “Four Takes on La Flor: House Rules,” Film Comment, January-February (2019), 33.

- 2Andréa Picard, “Four Takes on La Flor: The Long View,” Film Comment, January-February (2019), 30-31.

- 3Andréa Picard, “Four Takes on La Flor: Flowers and Trees,” Film Comment, January-February (2019), 33.

- 4Mariano Llinás, “Director's Statement,” Press Kit, 2019. [French version] You can find a collection of French articles on the film, including the text and interview in Cahiers du cinéma, here.

- 5Jordan Cronk, “Teller of Tales: Mariano Llinás on La Flor,” Cinema Scope, 76 (2019).

- 6Fernando Ganzo, “El Pampero à l'heure de La Flor,” Trafic, 109 (2019).