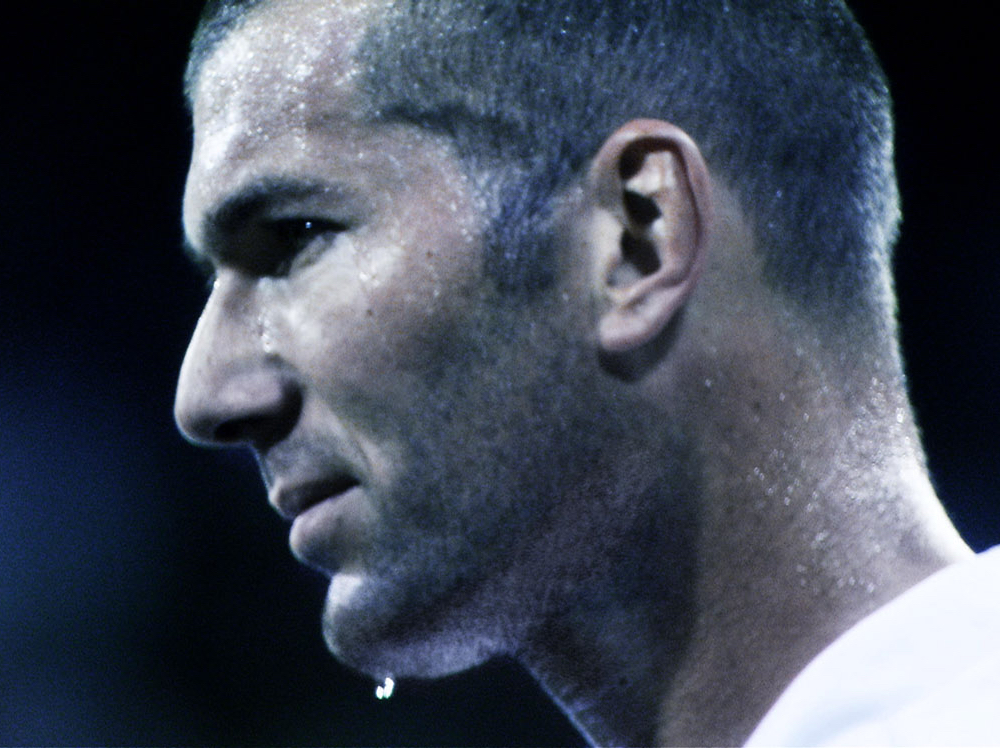

“In Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait experimental filmmakers Douglas Gordon and Philippe Parreno set up seventeen cameras to follow Real Madrid footballer Zinedine Zidane through the course of an average game. The detail of such images, including many close-ups, is stunning, but it is the sound which sets it apart from any other digital photography. The combination of silence, movement and deep breathing, the tap of a booted heel on the ball, a hand wiping away sweat from a damp forehead, produces a remarkable, contemplative cinema – a cinema of extra-materiality produced through noise.”

Davina Quinlivan1

“Gordon and Parreno scoured the world for a camera lens able to provide the maginifying power they needed to achieve the extreme close-ups of Zidane they would employ in the film, eventually securing the loan of an experimental zoom lens not yet in commercial production from British military sources. They experimented with complex strategies for positioning and using the seventeen synchronized 35-mm and high definition video cameras used to capture the game.

Gordon and Perreno are reputed to have also marched their director of photography, Darius Khondji, and his camera crew through the Prado Gallery in Madrid so they could explore a range of forms of painted portraiture as preparation for the shoot, hoping that the camera operators might find inspiration among the Goyas and Velasquezes for their photographic framing and portrayal of Zidane on the field of play […].”

D. Bell2

“Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait undermines the spectacular conventions of television by highlighting at all times the material processes of film making. In the film, the use of spoken commentary is minimal; there is no interest in following the ball or in showing goal-mouth action; elevated camera angles that allow the whole game to be depicted as a collective drama or agony are largely absent; and during the half-time interval the match is not removed from history through the spectacular speech of television punditry but rather considered in tandem with other events occuring simultaneously in the world.

[...] By contrast, nothing really happens in Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait, and even the goals scored in the game and Zidane’s sending-off at the very end of the work are de-dramatized. As in Bill Viola’s video projections, the slowness of the film, created through lingering close-ups on the player’s face and through repetitive soundtrack, provokes an experience close to boredom in which the viewer becomes acutely aware of time, feeling its rhythm in her/his body. This return to temporality is, by necessity, a return to everything that the de-personalized, fractal time of neo-liberalism finds impossible to admit: gravity, death, the event - and, ultimately of course, politics. For what else is politics if not an intervention into the current distribution of time? Something, that is, which questions the rhythms of the present, evokes the ghosts of history and interrogates the ever-decreasing borderline between labour and leisure.”