“Money, well-timed and properly applied, can accomplish anything.”

Barry Lyndon’s mother

“The all-but wordless scene where Barry and Lady Lyndon, who go on to marry, face each other at the gaming table and share their first kiss, stands for me as one of the most superb moments in cinema. Partly it’s the restrained, unhurried step of Schubert’s piano trio, partly it’s Marisa Berenson enigmatic loveliness as Lady Lyndon; it’s the depths hinted at in each surface gesture, how she looks all but ill as she realises she’s falling in love with him, how she distances herself in order to come closer. Most of all, the scene is a candlelit, melancholy masterclass in the art of glances, an object lesson in how film seduces us into looking, and looking again.

Admittedly, Kubrick regards events from a distance, and in memory the film offers a series of tableaux and interiors, people grouped in rooms, or marching ranked in battle formation. Close-ups are few, and when they come their rarity renders them all the more powerful. The film’s reputation for chilliness mistakes irony for a passionless lack of engagement. In fact, desire and, in particular, rage energise the film, bursting apart its studied Enlightenment equilibria. At the heart of the movie is the symmetrical, organised violence of the duel. Barry’s father’s death in a duel kicks off the film. This civilised ritual of aggression chimes with the movie’s stately ordering of profound disorder. Even that astounding scene where Lady Lyndon falls in love with Barry seems structured like a kind of duel, the two facing each other, and Barry’s insistent stare a soft challenge that overwhelms his prey.”

Michael Newton1

“For months they tinkered with different combinations of lenses and film stock to make this possible, before getting hold of a number of super-fast 50mm lenses developed by Zeiss for use by Nasa in the Apollo moon landings. With their huge aperture and fixed focal length, mounting these was a nightmare, but they managed it, and so Kubrick’s vision of recreating the huddle and glow of a pre-electrical age was miraculously put on screen.

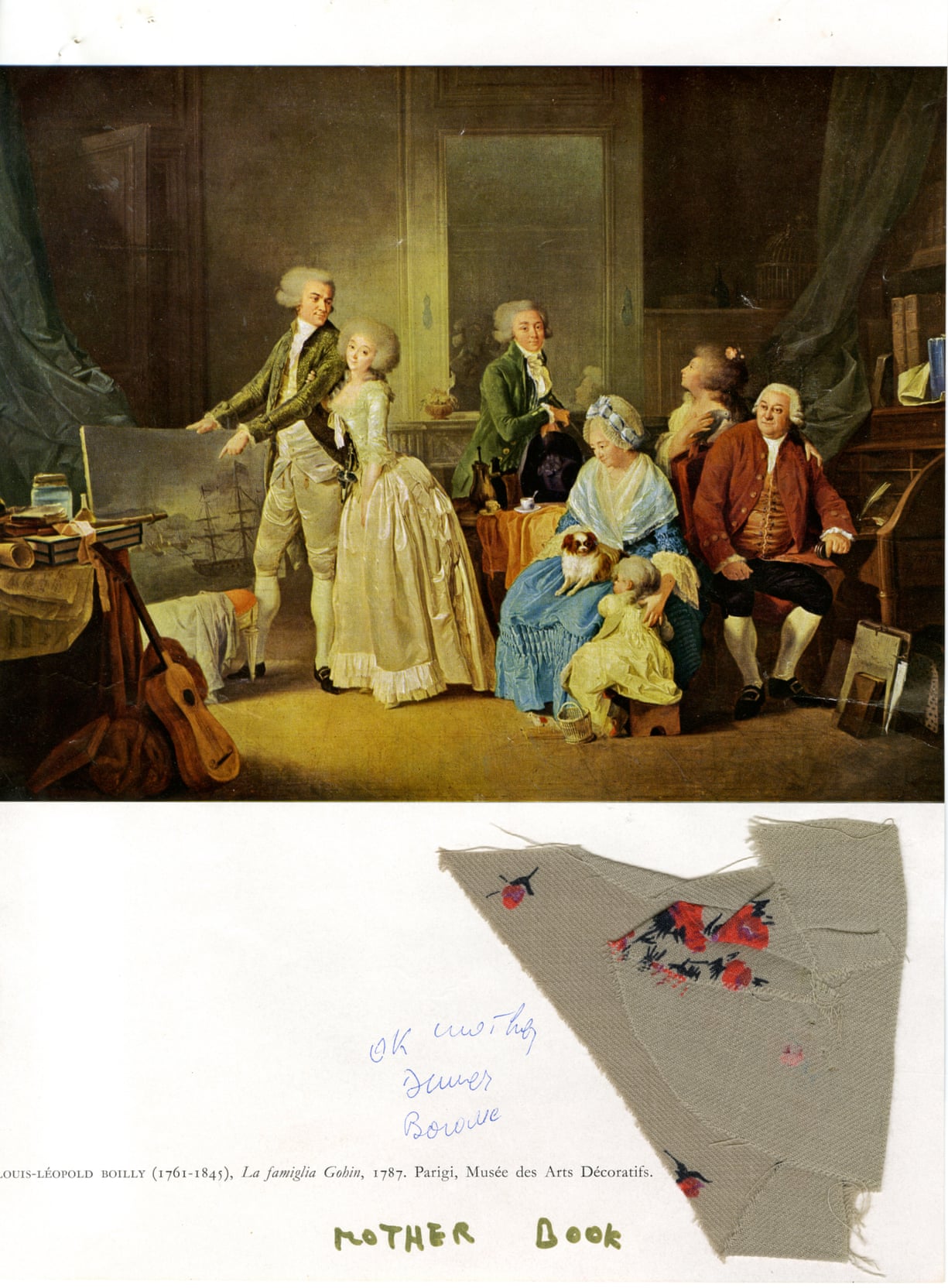

The stately, painterly, often determinedly static quality of Barry Lyndon was at least in part dictated by this stylistic choice – lit only by candles, the actors in the many sequences of dining and gambling were under instruction to move as slowly as possible, to avoid underexposure. But it fits perfectly with Kubrick’s gilded-cage aesthetic – the film is consciously a museum piece, its characters pinned to the frame like butterflies.”

Tim Robey2

“Stanley would look through art books himself; he would pick out paintings which he would then give to the designers and say, ‘This is what I want.’ Stanley would pick up on and pay great attention to little details: for example, he noticed the paintings showed us that tables were often placed near windows; this makes total sense as daylight was so important. We don’t really think about that sort of thing now.”

Jan Harlan3

- 1Michael Newton, “Barry Lyndon: Kubrick’s vision of a compromised life,” The Guardian, 29 July 2016.

- 2Tim Robey, “Kubrick by candlelight: how Barry Lyndon became a gorgeous, period-perfect masterpiece,” Tim Robey, The Telegraph, 27 July 2016

- 3Jan Harlan, “Stanley Kubrick: the Barry Lyndon archives – in pictures,” The Guardian, 10 December 2015. Image with thanks to the SK Film Archives LLC, Warner Bros. and University of the Arts London.