A look at the last 60 days of Van Gogh’s life. After leaving the asylum, he settles in the home of Doctor Gachet, an art lover and patron. Vincent keeps painting amidst the conflicts with his brother Theo, the torments of his failing mental health, and an affair with Marguerite, his host’s daughter.

Charles Tesson: Van Gogh, le plus grand ?

Maurice Pialat: Un jour, on a décidé que Van Gogh était le plus grand peitnre de tous les temps, c'est une définition absurde.

Pour vous, ce n’est pas vrai?

Bah, non, c’est un peintre, c’est pas mal.

Charles Tesson en conversation avec Maurice Pialat1

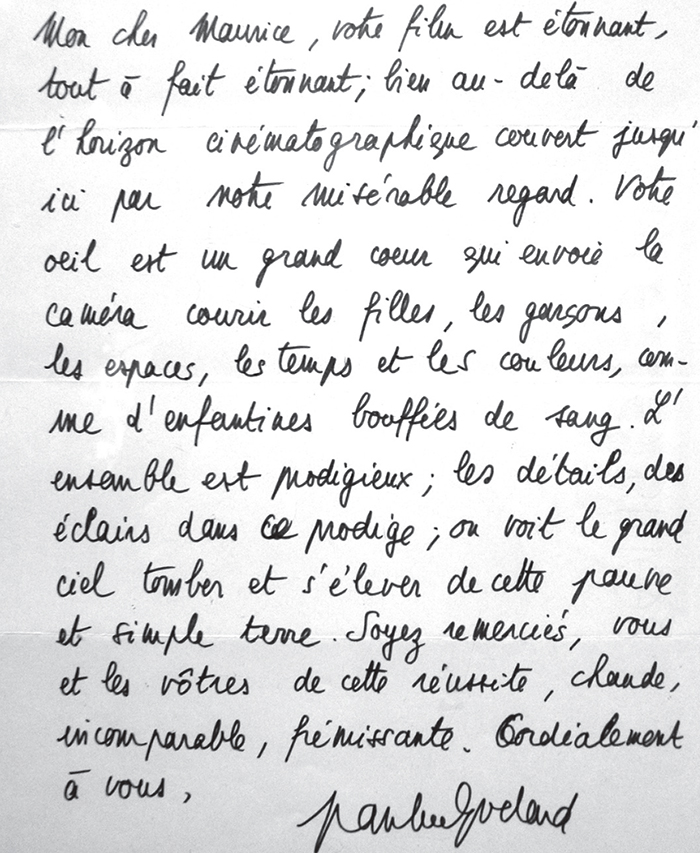

Letter by Jean-Luc Godard to Maurice Pialat:

My dear Maurice, your film is astonishing, totally astonishing; far beyond the cinematographic horizon covered up until now by our wretched gaze. Your eye is a great heart that sends the camera hurtling among girls, boys, spaces, moments in time, and colors, like childish tantrums. The ensemble is miraculous; the details, sparks of light within this miracle; we see the big sky fall and rise from this poor and simple earth. All of my thanks, to you and yours, for this success – warm, incomparable, quivering. Cordially yours, Jean-Luc Godard2

“Je ne suis pas pour la biographie. Il y a un paradoxe avec Van Gogh, parce que c’est quelqu’un que tout le monde croit avoir vu, à travers les portraits, à travers les photos ; il y en a une de lui à 16 ans et une autre où on le voit de dos à Asnières, mais vraiment de dos ! Alors on cherche une espèce de ressemblance pas évidente, parce qu’il n’y a rien d’évident là-dedans. La plus connue, la plus recherchée, c’est celle de Kirk Douglas dans le film de Minnelli, par qu’il avait tout copié, le chapeau, la lumière, etc., c’est comme Hitler, il y avait la mèche et la petite moustache. C’est surtout la ressemblance avec un espèce d’imagerie, d’iconographie, que madame Jo, sa belle-sœur, a su si bien créer. Ella a entièrement fabriqué le mythe.”

Maurice Pialat3

“Wie nog steeds allergisch is voor Van Gogh, loopt nu wel de kans de mooiste en zuiverste Van Gogh-film ooit gemaakt, te missen. Pialat verricht namelijk een waar wonder. Na alles wat er over Van Gogh gezegd, geschreven en gefilmd is, na alle romantische cliches over de gekwelde en lijdende kunstenaar die het zicht op hem verduisterde, slaagt Pialat er toch in ons de oren en de ogen te wassen en onze blik op Van Gogh grondig te zuiveren.”

Hans Kroon4

“Pialat films this narrative with a lack of emphasis complementary to [Vincte Minnelli’s] Lust for Life’s vivid hysteria. The profound difference between the films can be located in their respective central performances. Kirk Douglas dominates Lust for Life, his voice and body bursting through every frame, his flame-haired face contorting in pain as if about to turn into a “dark-side” monster like Dr. Jekyll or Bruce Banner. It is a performance attuned to the public myth of Van Gogh, the events of his life, and the intensity that sears his letters, extracts from which provide much of that film’s contextual information, locking us further into his worldview.

Douglas is so immediate because Minnelli, through dialogue, scenario and mise en scène, gives privileged access to Van Gogh’s feelings and thoughts. Pialat keeps his artist at a distance, never externalising beyond what would arise “naturally” from conversation; Van Gogh is often marginal to or even absent from whole scenes, “everyday” vignettes that have nothing directly to do with him at all. Dutronc’s is one of the great performances, coiled yet passive, its sullen calm occasionally breaking into banal violence, but mostly rendered through walking, painting, listening, doubting, thinking thoughts we can only guess at (Dutronc said of Pialat himself, “Like all directors, what’s in their head is a secret”). Minnelli gives us enough reasons to make Van Gogh’s death inevitable, even understandable. Watching Pialat’s film, the suicide is as arbitrary as any of Van Gogh’s other gestures. His death is not viewed through a hagiographic, myth-making glow, but is bitter, silent, painful, spasmodic and dragged out.”

Darragh O’Donoghue5

“The simplicity of Van Gogh’s life is inscribed in the depurated surface of the film. Its main feat is its concision. Historical reconstitution has been wrested away from its usual elaboration. In fact, the accuracy of historical reconstruction doesn’t interest Pialat – we can see, for example, how the famous question of the chopped ear (even though it is mentioned in the film) is ignored by the physical characterization of Van Gogh. Pialat is focused on the presentation of a man and the battles within him apart from his name (thus, we rarely see his paintings and, even more rarely, his most iconic ones).”

Sabrina Marques6

- 1Charles Tesson, “Pialat et Van Gogh”, Cahiers du Cinéma, février 2003.

- 2Translated by Craig Keller.

- 3Charles Tesson, “Pialat et Van Gogh”, Cahiers du Cinéma, février 2003.

- 4Hans Kroon, “Maurice Pialat geeft ons Van Gogh terug als raadselachtig individu,” Trouw, 24 september 1992.

- 5Darragh O’Donoghue, “Van Gogh,” Senses of Cinema, July 2006.

- 6Sabrina Marques, “Pialat & Van Gogh: Fellow Outsiders,” from the booklet of the 2013 Masters of Cinema UK Blu-ray, reproduced on Craig Keller’s Cinemasparagus, 20 October 2015.