Ten Films

![(1) Zerkalo [The Mirror] (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1975) (1) Zerkalo [The Mirror] (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1975)](/sites/default/files/1.%20Zerkalo_10_720.png)

Zerkalo [The Mirror] (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1975)

Tarkovsky’s heart-breaking masterpiece. For some reason this film is considered obscure, but it is extraordinarily clear to me, as close as cinema can get to dealing with autobiography, childhood memories. Just to think of the evocation of his absent father through his poems make me shiver. Everything Tarkovsky ever touched, including his masterful essay on cinema – Sculpting in Time, which every film student should read – is blessed with a grace that makes him, beyond cinema, one of the greatest artists of the 20th century.

Le diable probablement (Robert Bresson, 1977)

Bresson had an overwhelming influence on my early approach to movies. I felt that if cinema could reach the heights Bresson had reached, then it was worth it to follow that path and devote one’s life to its practice. As it is with all such influences, you have to somehow outgrow it, if only to become yourself. But through the years my awe of Bresson’s work has remained intact. This film, which deals with the Seventies, a period when I was a teenager very similar to the one portrayed by Antoine Monnier, has always held a very special place for me.

![(3) In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni [We Turn in the Night, Consumed by Fire] (Guy Debord, 1978) (3) In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni [We Turn in the Night, Consumed by Fire] (Guy Debord, 1978)](/sites/default/files/4.%20vlcsnap-2020-03-06-20h51m29s855.png)

In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni [We Turn in the Night, Consumed by Fire] (Guy Debord, 1978)

I was 25 when I saw this extraordinary film, but I had already read it a few times – its commentary track, a striking essay by Guy Debord, maybe one of his most important, had already been published. It is about youth, about historical opportunities, about time passing too quickly, about the vanity of all things, about the world falling apart and the shrinking possibility of any revolutionary alternative. Any generation can read it, see it, and feels its dark fascination echoing through its own history.

L’enfant secret (Philippe Garrel, 1982)

I don’t know if this is Philippe Garrel’s masterpiece, he has made many great movies. But certainly, this is the one that has had the most profound, the most defining influence on me. Shot in the late Seventies, released in 1982, after long years in limbo, this is Garrel’s farewell to the abstraction and experiments of his first period. Painfully, and self-destructively, he explores a new territory of raw narration, a poetic autobiography, which reopens for other filmmakers, including myself, the possibility of a modern, radical, figurative cinema.

Ludwig (Luchino Visconti, 1972)

These days, Visconti seems largely forgotten, overlooked as some kind of decadent aesthete, a baroque stage director who turned to cinema and made a few flamboyant period pieces in his time. So, maybe it’s time to check him out again. Visconti is one of the few geniuses cinema has produced. The scope, the depth, the mad ambition of his greatest achievements are somehow beyond cinema, relating – as the greatest movies of Pasolini also do – to the very history of the 20th century, and the terrifying changes European societies have undergone. Yes, Visconti is a figure out of the 19th century looking at us, but not as an academician, rather as a daring modernist putting to shame the timid transgressions of contemporary artists. Ludwig is his crowning achievement, even if he never saw it finished.

![(6) Fanny och Alexander [Fanny and Alexander] (Ingmar Bergman, 1983) (6) Fanny och Alexander [Fanny and Alexander] (Ingmar Bergman, 1983)](/sites/default/files/6.%20Fanny.jpg)

Fanny och Alexander [Fanny and Alexander] (Ingmar Bergman, 1983)

No filmmaker has had a greater influence on me than Ingmar Bergman, and I had the privilege of meeting him and publishing a book of our conversations. He has been a model I have been obsessed with all my life. He is an extraordinary writer, possibly the greatest playwright of the 20th century, and one of the great inventors of forms in the history of cinema. He redefined himself many times, creating masterpieces in each of his various periods. He also wrote one of the great artistic memoirs of his time, Laterna magica. Fanny and Alexander, which he considered his last film even though it predated the sublime Saraband by twenty years, is a testament, a summation, and the transcendence of all he had previously achieved. At 51/2 hours, it is, like Ludwig, bigger than cinema.

Invocation of My Demon Brother (Kenneth Anger, 1969)

Kenneth Anger is a great filmmaker. Period. He is not an experimentalist, a Satanist (not only) or a magus, even if that kind of comes closer to describing him. He invented his own cinema, as Andy Warhol did, a rival to Hollywood, a rival to basically everything that had been made in movies since the magical, mysterious silents. He believes that movies deal primarily with the invisible. He may be right.

La maison des bois (Maurice Pialat, 1971)

The hidden jewel of French cinema. Possibly the greatest film in the history of French cinema. No, I am not overdoing this. Pialat has defined ever since his first feature a raw naturalism that makes most of traditional cinema feel fake, contrived. His films are both angry and tender, dark and elegiac, intense in the way life is and movies rarely are. But there is also another Pialat – happy, luminous, reconciled, possibly, after Renoir, the truest heir of Impressionism – who comes into full bloom with La maison des bois. Shot as a mini-series for French TV, it gives Pialat more time, more space, a consistent budget and none of the pressures associated with the business of cinema. The joy, the light, the very grace of filmmaking radiate in every shot.

Le comédien (Sacha Guitry, 1948)

Guitry is one of the most fascinating figures in the rich history of French cinema. He was already past 50 and an accomplished playwright, actor and stage director when he started making movies, in the early ‘30s, at the moment the talkies gave him an opportunity to bring to cinematic life his virtuosity in dialogue, the constant daring of his dramaturgy, his sharp eye for social criticism, his formidable screen presence and his love for actors; most of all actresses, and specifically his wives, each of them defining a distinct period of his work. Le comédien is the biography of his father, the great actor Lucien Guitry, who was the single-most important person in Sacha’s life. In this cruelly underrated masterpiece Guitry expresses his admiration, his affection, the conflicts that marred their relationship and most of all his love for the theatre, the memories and melancholy of life spent on the stage. For me it is up there with French Cancan.

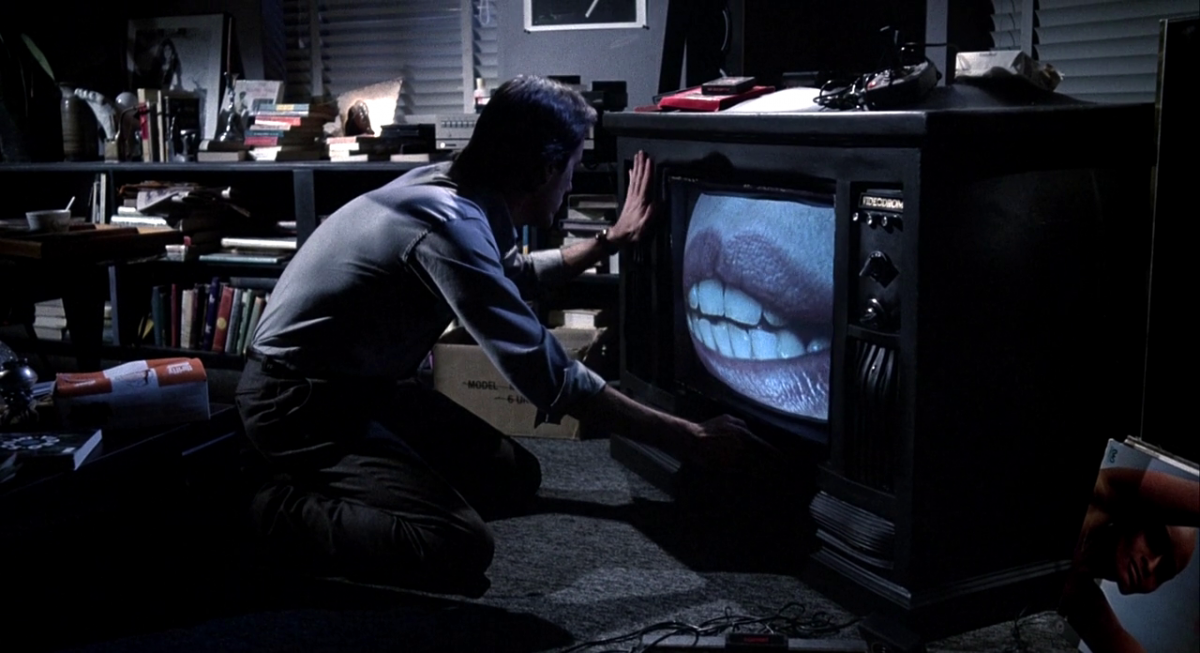

Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1983)

I have been a fan of David Cronenberg ever since I saw Rabid in a suburban multiplex when I was in my early 20s. He started as a genre filmmaker, but for me he was never genre, he was a science fiction auteur right from the beginning, and he has grown with almost every new film. Videodrome is one of his masterpieces, for me the most important. When I saw it, it struck me as the film perhaps in closer touch with the undercurrents of modern society than any other I had ever seen, a visionary work. At the time it didn’t even have a French distributor, and I did my best – I was writing for Cahiers du Cinéma – to lobby for its release. It has stayed with me since, and its daring, abstract, poetic imagery still haunts me.

Originally published in Olivier Assayas, edited by Kent Jones (Vienna: SYNEMA – Gesellschaft für Film und Medien, 2012)

Image (1) is from Zerkalo [The Mirror] (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1975)

Image (2) from Le diable probablement (Robert Bresson, 1977)

Image (3) from In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni [We Turn in the Night, Consumed by Fire] (Guy Debord, 1978)

Image (4) from L’enfant secret (Philippe Garrel, 1982)

Image (5) from Ludwig (Luchino Visconti, 1972)

Image (6) from Fanny och Alexander [Fanny and Alexander] (Ingmar Bergman, 1983)

Image (7) from Invocation of My Demon Brother (Kenneth Anger, 1969)

Image (8) from La maison des bois (Maurice Pialat, 1971)

Image (9) from Le comédien (Sacha Guitry, 1948)

Image (10) from Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1983)

This text is published in the context of the State of Cinema 2020 / Olivier Assayas, Friday 26 June 2020 at 20:00 on Sabzian. More information about the evening can be found here.