Exiting the Lion’s Den

A Conversation with Helga Fanderl

Helga Fanderl (1947) has been making films since 1986. After her studies of German and Roman languages and literatures, she studied film under Peter Kubelka in Frankfurt and Robert Breer in New York. Since the mid-1980s, she has created a singular body of work. Always shot on silent Super 8, and edited in the camera, her films are characterized by an attempt to capture the fleeting poetry of everyday life by the means of short forms. Deeply connected to her filmmaking practice is Fanderl’s concept of programming and organizing screenings, forming a symbiosis: “Each programme consists of a composition of individual works that form a temporary ‘film’ for the duration of the screening, a dense and loose fabric of references, correspondences, and contrasts between motifs, colours, rhythms and textures.” Her films have been shown in cinemas, museums and galleries across the world. She lives and works between Berlin and Paris.

Martin Klein: You came to film quite late, as you often emphasize. You studied literature and were interested in poetry. Did you work artistically before film? Did you write, poems for example?

I loved poetry and have written poems myself. When I studied literature and gradually got to know the work of great poets, I became convinced that my writing would never reach the level of what I loved. I also felt very unsure of myself. I had a deep desire to be a poet, and I was not alone: In my circle of friends, we exchanged poems, but we were no early geniuses like Rimbaud.

I discovered filmmaking by chance. Through an early short film that I thought was successful, I found out what I could create without language, only with the language of a small silent Super 8 film. This was overwhelming. I filmed quite a lot, and I realized that my approach to the world was very visual, although language still matters to me: I studied languages and love foreign languages, I lived abroad, I love poetry. But it was something else to create purely visual films.

How did this first contact with the Super 8 come about?

By chance. When Urs Breitenstein, a Swiss artist, had finished his film studies with Peter Kubelka in Frankfurt, he wanted to earn a little money giving a workshop beautifully named ‘Super 8 as an Artistic Medium’. He asked me, among others, if I wanted to participate. This came as a surprise to me since I had nothing to do with film at the time. After some back and forth, I decided to become a paying member of the class in order to do Urs a favour. And I was curious.

It was a nice little group. The others knew already what experimental film was and were ambitious. Some hoped to approach Kubelka or the Städelschule. I was the only one who did not know about experimental film. We bought our own Super 8 cameras, which was very easy then in the central station district of Frankfurt, where I also found my first Super 8 projector and some other equipment. We went out together and filmed in the same place. In those days, you got the films quickly developed. I could ride on my bike to the lab, drop off the film and pick it up developed the next morning – paradise in comparison with today. These experiences gave me my first perception of the Super 8 medium in all its facets: handling the devices, learning the languages of experimental film. The workshop was my first “school” until it ended when Urs found a good job.

There I was with my camera. I just continued to go out with this instrument whenever I had time, moving around with open eyes and filming what came across. At some point the question arose: is it just the pure pleasure of a leisure activity or is it more? To discover something unknown and a poetic quality in one of my early films caused a real change in my life. I gradually and carefully chose to venture into the lion’s den.

The lion’s den was Kubelka’s film class?

[Laughs] Yes. I developed a closer relationship with the medium and a different concept of film. Before starting to make films, I was not even a cinephile. I just went to the movies with friends. I saw experimental films only in Urs’s workshop and screenings that he organized in Frankfurt.

There are quite a few filmmakers from Frankfurt who went to study with Kubelka. Maybe you could say something about his methodology: How would you describe it? How did he lead his class?

The defining aspect, of course, was the focus on film, although he called his class ‘Film and Cooking as an Art Genre’. He admitted only students when he felt that they had potential, sometimes very arbitrarily. The class was held in a film room: there were a 16mm editing table, different projectors and equipment. He came in, sat on a chair in front of the editing table like a Buddha and asked: “Who wants to show something today?” At that time most of the students were informed by Kubelka’s teaching, centred on 16mm, and under the pressure to cope with his expectations: film as exact editing of image and sound, exact montage, artistic responsibility for every single cut. He was very decisive in his whole demeanour – not to say authoritarian: “I am God.” Sometimes it was scary. For this reason, I hesitated to approach him for a quite a while. I had heard that he could severely reject something and incredibly discourage students. And on top of that, there was my age. I was approaching my forties. Some professors were my age and the students much younger. Moreover, I was questioning myself: “What is this now? What am I doing? What do I want?”

However, I finally attended his class. Peter Kubelka was generous, allowing me to participate informally, on the condition of showing something. I still feel thankful to him. He asked if I was making films and I said: “I’ve just started making Super 8 films.” On the one hand, it was eye-opening how he analysed films, exciting and stimulating. But it’s also true that some of the ways he behaved with students seemed problematic to me. I was also afraid of a negative criticism that could harm my emerging little plants. I might not have coped well with this and even given up.

I had joined the class in the middle of the semester and avoided showing anything the whole time. There were always volunteers when he asked who was going to show. When the semester was coming to an end, he insisted that I had to show something. I projected two short Super 8 films: shots of architecture and situations in Bologna, a city where I used to live. It happened that the films found grace, not praise, but it was encouraging for me when he said, “You have a cinematic eye.” I didn’t know that about myself at the time, it only became apparent by making and seeing my films. And then the semester was over. I asked him whether I could come back. He said yes.

I was protecting the first film whose poetic quality I appreciated. When, in the following semester I finally showed it, Kubelka was immediately enthusiastic and offered for me to become his student. But the informal status suited me. I was working part-time, and I wanted to be independent. For this reason, I suggested that I remain his informal guest.

With a student ID, the students of the film class could attend the series of experimental film screenings that took place at the Filmmuseum Frankfurt once a week free of charge. For this reason, I decided to become an official visiting student. It was a parallel school, but not enough. It took me a long time to see many experimental films. Basically, this was okay with me. I felt unencumbered by examples of “good films” – unlike what happened with literature.

After some semesters, when I went to renew my student’s ID, I was told that I had been expelled, like all female visiting students. The new director of the Städelschule wanted to change the school that seemed to him to be too sleepy and not adapted to the art market. What a shock! I blamed myself for not having agreed to become a full-time student. I think that the male visiting students had not been kicked out, but that may be a legend.

Kubelka was on sabbatical in Chicago at the time. I called him and told him that I had been expelled. He said that was unacceptable and that now I should become a full-time student. I was not subject to an entrance examination. In total I had studied film for more than five years. Those were also difficult years. Kubelka had created a competitive system in his class. And I was an outsider, in terms of age and making Super 8 films, not so much appreciated at the time. Sometimes it was exhausting. In spite of all this, I’m glad that I went my own way. Of course, it is easier discovering yourself, your skills and the love for what you do when you are older. I did not need to build up an existence as an artist.

Kubelka told his students “you won’t be able to make money with this kind of film”, which was true. He himself became wealthy by teaching as a professor and giving lectures. Even today, only visual artists succeeding in the art world can make a living with their films. But this wasn’t my desire in the first place. If you love poetry, it’s not about a big audience or making money. It’s about doing it for yourself and sharing it with others. This is a different logic. You need to create a good situation for the reception of the work. I was lucky to find early recognition. I couldn’t believe it at the beginning and had to learn that others appreciated my work even before I appreciated it myself.

Was it also during this time that you discovered the way of working you’ve been using ever since – Super 8, silent, short films that deal with certain subjects?

Yes, but it’s also always a new decision. I think it was Kubelka who said that when you start filming, it’s good to film at first without film, so that you really master the instrument. At the beginning I tried to edit traditionally, but the tiny individual Super 8 photogram made it difficult to do precise and invisible editing. I was not interested in showing the material quality of the film strip and the film splice as filmmakers did in the seventies. Kubelka really understood my way of filmmaking. That was his forte. He encouraged me to do in-camera editing. He also helped me when it came time to show my films. Once the film class was invited to present a programme at the Filmmuseum Frankfurt. I was afraid of projecting in a cinema. I asked him what I should show. He suggested I make a selection of some films and create a sequence. This was my first experience with programming. It was amazing and fascinating to understand what a difference the order you show films in makes. I selected four films and tried many possible ways of combining them before I decided to put them together in the order that seemed best.

The bright projection of the 16mm films of my fellow students filled the screen. When I saw my Super 8 films projected from the booth, without hearing the sound of the projector, I did not recognize them. The lamp of a Super 8 projector is less powerful than the one of a 16mm projector. Super 8 was created for private home projections and loses luminosity in a bigger space. So, my experience and practice and accepting its specific qualities, pushed me to do my own screenings in a site-specific way.

For another screening at the Filmmuseum Frankfurt, I asked to set up the projector in the auditorium. The projectionist, who liked me, agreed to screen my films in the middle of the audience. I felt too nervous to project myself because I was not familiar with the projector. Knowing exactly when he needed to adjust the frame line or to focus quickly, I whispered in his ear what he had to do. I thought it was more reasonable to take care of the projection myself.

You’ve been showing your films for over thirty-five years now. Have you noticed that the contexts in which your work is shown are changing? For example, are you now shown more often in an art context, in galleries?

First of all, the separation between the visual arts and film was still very strict in Germany at the time. But Peter Kubelka taught film as art. Kasper König, a renowned curator who was at that time the head of Städelschule, supported my work when I still was a student. I had my first solo show at Portikus, the gallery for contemporary art founded by him. From the beginning, I was connected with the visual arts but not with galleries. What mattered to me were interesting spaces for my projections. For example, when I went to an opening of a gallery in a back building, a former workshop with a wonderful front of lots of framed small windows in Frankfurt, I thought that its size and simplicity were ideal for a Super 8 projection. The gallerist agreed. I made a series of three screenings there. What mattered to me was presenting my films in the right way, taking care of the proportions of the space, the appropriate distance between screen and projector, a bright projection and above all of the total darkening of the space. In cinemas it is difficult to find a high enough pedestal for the projector to project within the screening room. I did it my way and simply preferred other spaces.

I did not submit my Super 8 films to festivals. First of all, there was the problem of the films being projected from the booth. Second, I made a new programme for every screening. It did not matter in which year the films were shot. This practice is not compatible with the festival’s logic of the new. Maybe the freedom to show my work only in the right conditions has to do with my becoming a filmmaker only later in my life.

About your working method: You’ve always filmed on Super 8, but a few years ago you also started having blow-ups made on 16mm. What inspired you to do this?

The Super 8 camera, and this is important to me, is my instrument. Of course, it matters to show my films in the original format. When Kodak stopped producing Super 8 print stock years ago, I could no longer get prints from reversal originals. At first, I did not know how to go on. Almost everybody told me to digitize my films. This was out of the question for me. Digital is a different medium. After mourning for quite a while I thought that making 16mm blow-ups could be a solution to get new prints, at least sticking with the medium of film.

Dear Helga, thank you very much for the interview.

This interview was conducted during the second edition of exf f., which dedicated a series of screenings to the work of Helga Fanderl.

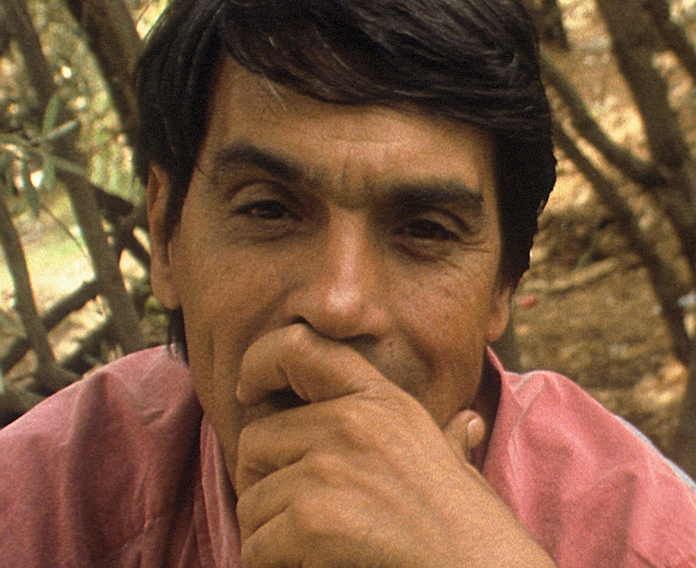

Image (1) from Flugzeuge I (Helga Fanderl, 2001)

Image (2) from Teetrinken (Helga Fanderl, 1993)

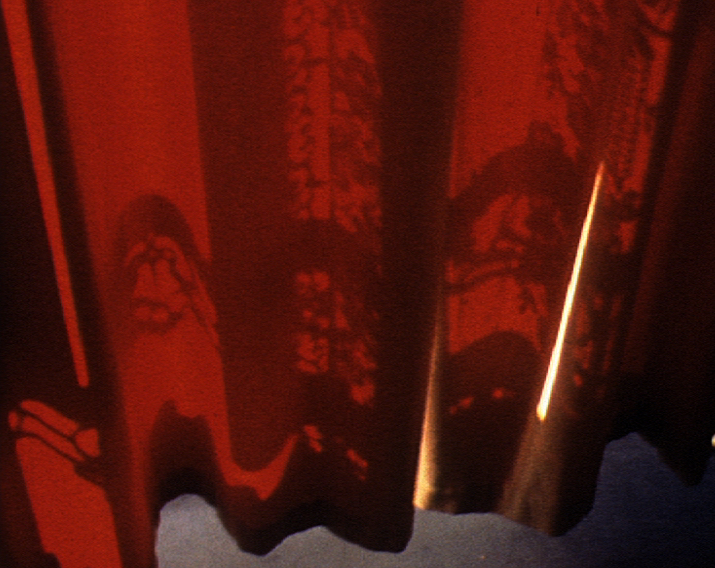

Image (3) from Roter Vorhang (Helga Fanderl, 1998)