Screening Room: Robert Breer

This text is an edited transcription of an episode of Screening Room, a Boston television series that ran for almost ten years from 1972 until 1981. It offered independent filmmakers a chance to show and discuss their work on a commercial affiliate station, ABC-TV. The series was developed and hosted by the filmmaker Robert Gardner, known for films like Dead Birds (1963), Rivers of Sand (1973) and Forest of Bliss (1986), With nearly one hundred episodes, the collection of guests of Screening Room is downright impressive. To name only a few: Les Blank, Jean Rouch, Ricky Leacock, Jonas Mekas, Stan Brakhage, Richard P. Rogers, Bruce Baillie, Yvonne Rainer and Michael Snow.

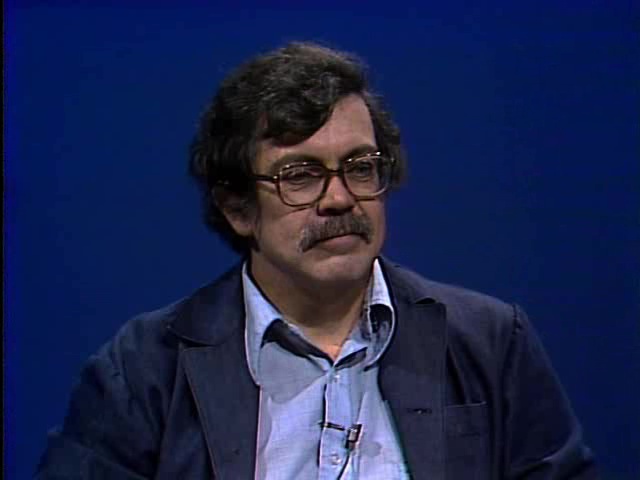

Robert Gardner: Today I have as a guest a major figure in the avant-garde cinema: a man named Robert Breer. He’s probably one of a handful of people that include himself, Stan Brakhage, Bruce Bailey… Both of those people, incidentally, have been on this program, and represent in the best manner possible what is experimental and independent in filmmaking, particularly in a branch of filmmaking that we’ve called avant-garde or experimental.

Robert, welcome to Boston and to Screening Room. It’s hard to know how to introduce you because you’re a man of so many different parts and talents. But you are known primarily as a filmmaker and this is primarily a program about filmmakers. So, let’s start with that anyway. Perhaps you could confirm or deny the rumor that you started in Europe, not in America. Is that right or wrong?

Robert Breer: Well, I started in Detroit, that’s where I was born. But it’s true that I started filmmaking in Paris, which is where I moved to after college. I started not making films. Well, I started making cartoons as a little kid.

You’re still making cartoons.

I’m still making cartoons in a way, that’s true.

But you started as a painter.

Yes. After the cartooning, a stint in the army doing commercial art army style, which was like being a French chef in the army.

You weren’t very useful?

I nevertheless got such an overdose of commercial art that when I got out of the army I went back to college. I had an inspiration that I didn’t want to do any more commercial art if I could help it. So, I became a serious artist.

In Europe?

No, this was still in school. After leaving school I went to Europe. Then in Paris as a painter I got interested in film as a kind of extension of painting.

How do you describe your painting? Does your film style flow naturally, gracefully and easily from what you were painting? Or is it that you were having trouble with your painting?

I was having trouble with a certain concept about painting, which was at a time before you were born. [Laughs] This was 1951, I made my first film in 1952. I was having trouble with a very rigid notion about painting that I was interested in and involved with, which was the school of Mondrian. The notion that everything had to be reduced to its bare minimum, put in its place and kept there. Since I at least once a week could arrive at a new absolute, it seemed to me overly rigid. I had a feeling that there was something there that suggested change as being kind of absolute, so that’s how I got into film.

So now you’re struggling with the added problems in your art of motion, space and time. Space is of course always an element in a painting.

Yes, space is there. I guess I still think of myself as a painter just using film. Film is very liberating for me, the idea that I could slide into art. Film is in motion, life is in motion. It seemed to me that if I could kind of sidle up to art by being in a fluid medium rather than having to declare “this is it for ever and ever”. It appealed to me in that way.

We’re not going to see anything that you made very early on?

Well the first film dates from 1956. It’s the first film that doesn’t look like one of my paintings. The earlier ones did.

I guess what I was getting at is that you did do some very geometric things at the beginning.

Yes, the first films were very awkward. I didn’t really know how to deal with animation. As soon as I started moving these shapes – which I thought were very elegant – around, they became very silly-looking. Mickey Mouse without ears in this case. I had to reassess the whole thing. Then I said “OK now I’m making films, forget painting!”

Why don’t we look at the first film that you’ve decided to show on the program, so the people can get an idea of what you’re talking about by having some images to refer to. We’re going to see a film called Recreation, which was made in 1956. Why don’t you say something about what to expect or not to expect?

You already mentioned the word “experimental” and I think it really applies in this case. This was an experiment to see what would happen if I changed, every twenty-fourth of a second, the image totally. As you know very well, there are twenty-four images per second in an ordinary film. Usually, they’re only slightly different from one another. In my case I decided to make each frame as radically different as I could. This means there’s an awful lot of information, whether you want it or not.

In successive frames?

Yes, in successive frames. There’s this great collision of different stuff. The impact on television will be less than it would be on a giant screen somewhere.

Are there any blackouts or dropouts?

Later. In this particular film, I keep the image busy. There is a soundtrack that appears and disappears from time to time.

Let’s go to Recreation, we’ll be back in a moment.

[Screening of Recreation, 1956)]

Robert, clearly when discussing something like this, the immediate feeling on my part is to identify you with somebody. Because this comes quite sudden and, in some way, unexpectedly out of the conversation that we’ve just had. Not having mentioned anything more than that you were in France. There must have been other influences besides Mondrian.

Oh, there’s no Mondrian in this film. I should first explain how the soundtrack is in French in case nobody noticed. However, it’s a kind of nonsense poetry and meant to just parallel, percussively, the images. It doesn’t matter if it’s understood or not. No, obviously it’s not Mondrian there. Of course, there is a tradition of the avant-garde film, which I find that I have to explain quite often. People are aware of the history of painting a lot of times when they’re not of this particular branch of filmmaking.

You should mention a few names.

My lineage, I guess, would start with Hans Richter, who was the first man to consider film as a possibility for painting, as a painting surface. Or one of the first, in 1920, Viking Eggeling, who was a Swedish counterpart to Richter. Then there was Fernand Léger, who, as a painter made that very important film that had a lot of impact on me: Ballet mécanique [1924]. Man Ray is another case. Then there was a kind of a hiatus in the thirties.

You don’t include Duchamp in this list of people.

Well, sure. Although Duchamp didn’t make more than two film efforts, but certainly his esprit was behind all of this. The other thing too is that in 1956, when it comes to painting, Jackson Pollock had already gone by.

This is moving from Mondrian towards Jackson Pollock perhaps, or at least to abstract expressionism. What I’d like to do is see that next film A Man and his Dog. Let’s see it and then we’ll say something.

[Screening of A Man and his Dog Out for Air, 1957)]

The thing that I seem to feel you’re most concerned with is space. You’re defining space in some fashion with this bird moving about in the frame. And yet you spoke of yourself as somebody who is interested in using film as a painter would use a canvas, that really you don’t consider it all that different.

Well, the graphic part of the film is in that I draw, I like to draw. So, my films are made up of drawings. The space… I think of the screen as the way I used to think of a canvas. That’s just part of the painter’s discipline.

We’re going to get into your actual technique, which is to use cards, which is a long cry from a canvas. But here, what actual surface do you use to compose these things in? I mean, you obviously can’t draw on a piece of film because it’s too small, but you draw on something larger and work in front of the camera.

That’s right, the animation process is one picture at a time. And normally you use eight by ten piece of paper. That’s what I used for A Man and His Dog. The next film we’re going to see, 69…

Let’s see 69 now and then let’s get back to actual working solutions or at least working methods.

[Screening of 69, 1968]

Since you can’t obviously immediately make your mark on the film itself, you have to have some kind of mediation or method for getting the image. Was 69 the beginning of a new way of working or was it in fact A Man and His Dog Out for Air? I know cards are important to you. Maybe you could try to explain that a little bit?

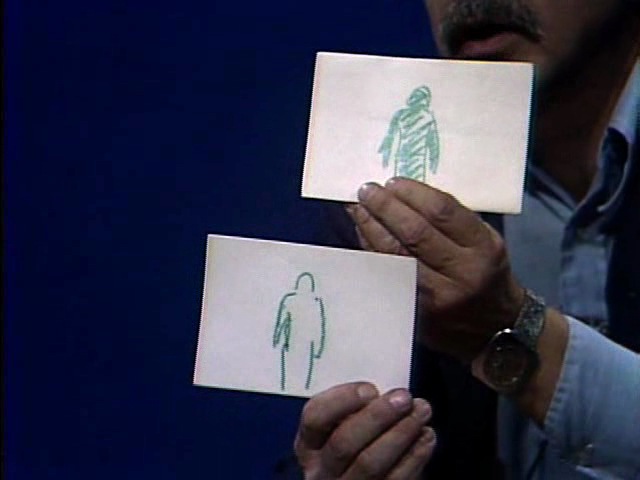

A Man and his Dog was made in 1957. So, it’s ten years later that I made 69. There are a lot of films in between. I gradually developed a technique that’s kind of unorthodox compared to normal animation, the Disney fashion with clear celluloid, larger sheets. I finally started working smaller. When they eliminated the finger of Mickey Mouse, they saved a lot of ink and several thousands of dollars. Animation is made up of all these individual steps. Cutting down on size meant that I wouldn’t have to draw as much. You know, I have to do thousands of pictures for one film. So, I cut the size down to four by six and then started using index cards that you buy in a stationery store because they’re stiff. You can flip them as you’re going along and see very well what you’ve got. It’s like those old kids flip books. I don’t know if you can get a good picture of this, but there it goes. This is a figure from a film we’re going to see a little later, Gulls and Buoys. These are the original drawings.

But is that particular sequence in Gulls and Buoys? It doesn’t seem.

Yes, it is. The idea of using the cards is therefore just a convenience and it’s been a very good one. My hope is, and I see it happening, is that people like myself, independently of big studios that are interested in making animated films, will come upon simplified methods to do it. It’s been too complicated. The cards make it a lot easier to work.

So not only is it a cheaper way of working, because it’s not as much labor involved in it, but it’s also a way of sort of previewing your film.

Yes, of course the old animators could flip their sheets of paper. They got to do that. But there are other shortcuts which I won’t have to go into. But having to do with the actual photographing of them, I have an automatic machine now that flips them away from the camera. So, I can shoot an animated film almost as quickly as you can shoot an ordinary film. Any shortcuts like that make it seem less a tedious business and more direct. But you mentioned that I’m not working directly on film. Of course, Len Lye and later on Norman McLaren actually did that. That is possible.

But not on 16 mm, did they?

No, on 35 mm. It has its own limitations. I think that’s too small a format. You can’t see successive images. So, this is a compromise between those extremes.

What I have also seen in your films, which I think is really important for you to respond to, is the element of humor. Because very often abstract cinema gets very solemn and serious. Yet, I don’t know of any film of yours which doesn’t have some joke in it or a series of jokes in it.

Well, that’s something I can’t deal with directly. It seems to be a compulsion of mine, Irish ancestry or something. But I also feel the way you do. I’m not wedded to abstraction as such. I’m interested in everything that moves, whether it is figurative or not. I don’t know, I like funny things. What can I say? I’m interested, though, in a fractured image. I like the idea that the image jumps around a lot. I like to work on different levels. Humor might be one of the levels, it’s part of life. Some things are funny, some are sad. I like to include them all.

They kind of have to be sight gags, don’t they? Because if you’re working in an abstract mode, that is to say not a narrative mode, then you can’t tell a story, and not even a funny story.

I don’t rule that out, but I usually don’t tell stories. A Man and His Dog has a little denouement, which comes as a kind of payoff. I don’t know. I guess animation lends itself to surprises, just the process of making an animated film. You like to surprise yourself. For one thing, you can spend all day on a three second sequence, and there is a kind of tedium that could set in. I like to keep myself alive during the making of the film, and maybe I hope that gets onto the screen.

How about the titles of your films? Do they do they have really great significance? Or are they kind of tags you put on the film?

It’s like naming children, it doesn’t matter. You can call your child “Horrendous” or whatever you want to call it. Sooner or later, the child gives the quality to the name. I’ve relieved myself of feeling badly about some ill-chosen titles with the assumption that sooner or later the title will lose its original meaning and take on that which it’s a label of. I don’t know otherwise.

Well, the title of your the next film of yours that we’re going to see is Fuji.

Oh, I thought it was Gulls and Buoys.

Oh, wait a minute. You’re right.

I was afraid. Gulls and Buoys being a pun, that’s why. I’m not especially fond of that title, that’s why I mentioned this. I hope it’ll go away in terms of it being only a pun.

You mean not the title. You’re not like a poet; you’re not going to rewrite it.

I’m annoyed by titles and it nevertheless seems to be a necessary thing for films. So sometimes I express my annoyance by a perverse act like choosing a dumb title.

Do you have any other cards from Gulls and Buoys, or should we look at Gulls and Buoys and then maybe look for some cards to show afterwards?

Yes, I think a thousand pictures is worth one card. [Laughs]

It’s usually the other way around. But let’s see Gulls and Buoys now and we’ll come back.

[Screening of Gulls and Buoys, 1972]

I think it’s worth talking about another technique which is obvious in this film, that is rotoscoping, which has been done here as well as cards.

Rotoscoping is a fancy name for any process which allows you to redraw, or rephotograph for that matter, stuff that’s already been photographed. In this case, I took some films that I had shot around Rhode Island, gulls and some buoys. I don’t think there are any buoys in it, but those birds, an occasional figure and so forth, were all shot live originally. Then I projected them up through a window on a table at one frame at a time and made a little drawing on the card of each one of those figures.

Here are two images from that film of that figure that I showed you before I flipped them. Each card represents one twenty-fourth of a second, and they follow one another. They’re actually tracings from live footage. At the same time, they’re not very accurate as you can see, they’re very loosely drawn. There are several thousands of them. Well, there are five hundred drawings of a seagull, for instance, to get that motion of the bird flying. Each one of those drawings is quite different from the previous one. I’m not slavishly following the image.

You drop out a lot of these images. You shot it on Super 8?

No, this was 16 mm. But I used Super 8 for a film called Fuji. And sure, I take vast liberties with the outlined image. Of course, half the film is made up imagery. It’s abstract, it’s blending those images that gives this particular quality to that film. Rotoscoping was invented way back, by Max Fleischer from Betty Boop, in the thirties. It just fell out of practice. The cartoonists in those days used to want to hide their techniques. Winsor McCay said that he drew Gertie the Dinosaur [1914] so that no one could accuse him of copying other animals because the dinosaurs didn’t exist. There was some question of artistic pride not to animate out of “reality”.

What were you doing before you used cards and rotoscoping? What is the quickest or easiest way to make an animated film?

Well, the principle being one image at a time.

Being a collagist, you can use anything.

As far as techniques go, there are a million different things you can use. Cut out pieces of paper and take one picture. Then move the thing and take another picture and so forth, underneath the camera collage. Of course, “col” comes from the word glue, and it means gluing different things together. That’s what you do when you edit a film. I think that probably the collage mentality could explain why these films seem to be bits and pieces, and unrelated, non sequitur arrangements of things. Since film is a sequence of one thing after another, I like to think as a collagist does. If we can look at the table here, maybe I’ll try to demonstrate.

Just don’t go too far away with that microphone.

No, I might cause trouble. I’m looking at my pocket for goodies. If we consider this table a piece of film here, the length of it, and these would be images that follow one another. I would say that here’s a movie. I’m making a composition right now out of things that aren’t related except in their time.

Do you want me to feed you any stuff?

Yeah, what have you got in your pockets? Let’s see, that’d be good. I put that here. Maybe I would rather have this here, and I’ll put this here.

I’ll get my Social Security card.

Okay, I don’t know how that’ll look. Let’s put it upside down so it won’t get too literary. Look, you got more things than I have. Anyhow, this is the idea. Let’s consider this with the film. This would appear first, then this, then this, and so forth. This is my attitude about composing film. I’m interested in the collision of these different things, physically, and not too much about what kind of story comes out of it.

Are you saying you’re interested in the collision of them sequentially rather than internally in the same frame because you’re not including all of them in the same frame?

No, I know that the film is going to grind out twenty-four images a second regardless of what I do. So that’s a given structure and within that I can play around. At least I think so.

But how much really deep pondering do you do about what you’re going to include as an object in the collage that eventually becomes a film? I mean, are all of these things randomly or systematically sought?

In those early collage films, I just try to grab everything I could think of. My cat walked by, I grabbed the cat and stuck him under the camera. I was trying to think in terms of opposites so that I could have as big a derangement of continuity as possible. So, I grabbed the cat to film him. Then I thought maybe a smooth, shiny object to follow the cat. So there’d be a contrast to see. I was experimenting in that case. But even so, that seems to be my tendency. I like the idea of opposites resolving each other.

Did you ever work with John Cage? I know you worked with Claes Oldenburg and Robert Rauschenberg.

No, I’ve never worked with John Cage. But I have great respect and admiration for him, I know him. I made a mutoscope a long time ago, which was kind of a rotary film thing, which he saw in a gallery and admired very much. I gave it to him. I like to think there’s some rapport there.

What did you do with Rauschenberg? Here’s a man who’s also a collagist, I suppose.

Well, Rauschenberg… I don’t know if this is the time or not. If we’ve been looking at this table at all, as anybody noticed, we’ve made oblique references. Can we?

I think maybe we could open up on it a little bit more.

Okay, a little while ago, there was an object up here. Looked like that, and now there’s one that looks like that. You and I both know that they’ve been roaming around on the table here ever since we started.

Even falling off the table. [Laughs]

Even falling off. [Laughs] They represent the other part of my career, which is making sculpture. Somehow, I went from painting to film to sculpture. I’m always making film, but I also got involved in making these kinetic sculptures. And that’s my connection with Rauschenberg. He is a marvelous guy and a great booster of other artists. One of the cases was when he bought several of my pieces when I had my first show. That parlayed itself into a collaboration on a theater piece. It was really his piece incorporating my sculptures, moving around and ended up as a television show and a piece of film.

We’re going to go to another film of yours, which I inadvertently said we were going to see instead of Gulls and Buoys, called Fuji. Is there anything that you ought to say before we see that?

Only that it’s this film that was based on some footage that I shot in Japan on the high-speed train that goes between Tokyo and Osaka. It’s all hand-drawn, but a lot of the image comes from this 8 mm film that I shot and was redrawn.

So, we’re going to see some rotoscoping?

Yes, this is rotoscoping.

All right, let’s see Fuji and then we’ll have a little time after seeing it to talk about it.

[Screening of Fuji, 1974]

I don’t think it would be any surprise to you if I mentioned that I thought probably you’d heard from people that your films are not the most accessible ones in the world, that they don’t follow traditional storylines or the idea of a story unfolding, with climaxes and denouements, that there is a great deal that seems gratuitous in them and yet has its own form and sense. There is something that was happening in this film, which is, particularly to some people perhaps, a little gratuitous. That is for the sound to disappear or for the screen to go black. What was, structurally speaking, the purpose of doing this?

It’s good you asked after Fuji because there are pauses in a lot of my films. In a theater situation, when the screen goes black, that means the whole room is dark. It’s as though the film broke or somebody pulled a power switch. There’s a lot more drama involved than on a television set. But in any case, I think of these films as theatrical films, I wasn’t aiming at television in any case. I use these blackouts as pauses, sometimes pregnant pauses because of the interruption. And I use music as a precedent for that. When there are pauses in the sound, it’s a pause in the rhythmic structure, if you like. Anyhow, in Fuji, it works out very well because there are a lot of tunnels on the way from Tokyo to Osaka, so I’ve always been able to explain those pauses that way. There was something else that came to mind while I was looking at the monitor and watching that film on television. I think it has to do with the edges being cropped on some films that weren’t aimed at television. I’ve been trying to think more in terms of centering the images. As a painter, I used to be very preoccupied with the borders of the frame.

But in a film like 69, you’re actually referring to space outside the frame. I mean, with the revolving columns and so forth. The hinge seems to be somewhere off screen.

On television, it’s off screen. On a normal screen, it’s right on the edge of the screen, again emphasizing the edge. But that’s right, I have to get with the television. I hear it’s going to become popular. [Laughs]

You hear it is going to become popular?

I think it’s probably going to settle down and stay.

[Laughs] What do you do about the audience, Robert? I mean, you say that you make these for theatrical situations.

I mean, I shouldn’t say theatrical in a normal sense, although Gulls and Buoys is going into theatrical distribution thanks to the National Endowment. And other films have been. A Man and His Dog was run with Last Year at Marienbad [Alain Resnais, 1961] for a long time.

Did that play at the Paris Theater in New York?

It played at Carnegie Hall.

We should see one more film, called Rubber Cement. Another engaging title, obviously with some meaning. How recently was this film made? I’m not sure of the dates on all these films. I think the last one we saw, Fuji, was made in 1974 when you were in Japan.

Well, this one is my latest.

Is it hot off the laboratory?

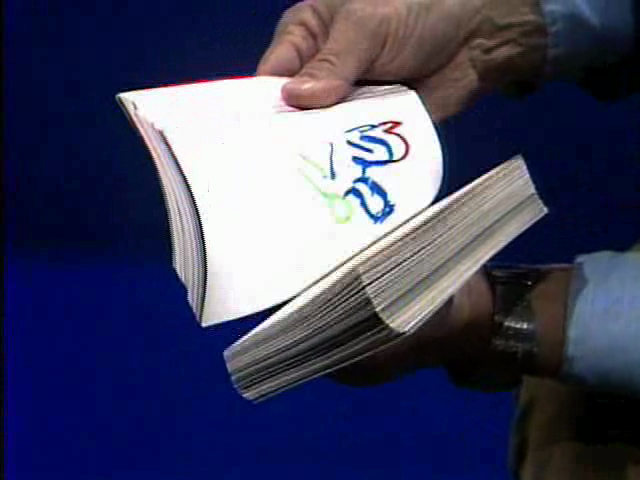

Anything of mine is usually lukewarm by the time it gets out because it takes a long time to make these. It took me a year and a half to come up with this one. A few months ago, I finished it. I’ve got a new one in the works now, but this is the last finished film. It’s a continuation of everything I’ve been doing really. A little bit of rotoscope. This is all done on these cards again. On this particular film, I had an opportunity to use the Xerox color copier, their new machine. It was a program initiated by the Arts Council and CAPS, a New York City thing. They arranged it so a certain number of artists could get at these Xerox machines, courtesy of Xerox.

George Griffin, incidentally, was on the program a couple of weeks ago, and he, you know his film Head, uses extensive sort of imagery from Xerox.

Oh, yes, that’s right.

There are certain parallels in your interests, isn’t there? I know he looks to you as a kind of, well, guru or something.

I don’t know about that, but sure, George is an animation fiend. My involvement with Xerox had to do with just playing with the color copier. I think George used his for…

Reproduction.

In my case, I just used it to generate strange color patterns. I was also grateful to the CAPS program for partially funding this film, and I made a little thank you title to them and threw in a “I tip my hat to Xerox” too. The only bad thing about that was that, going back quite a ways, I’m not a very good speller.

You spell it with a Z instead of…

I spell it with a Z. I don’t know whether people at Xerox have seen this film or not. I hope they take my gratitude in good faith. I kind of like it with a Z, and I wonder how perverse they can be to misspell it themselves.

I hope they’re not going to sue you for this.

I hope they change it, frankly, to Z-E-R-O-X. Anyhow, the color in that film, a lot of it comes from the Xerox machine. I don’t know how good an example I can give.

You have some cards.

I have some cards from it here.

This is a rather nice sequence because it is more collagist than the other ones.

Maybe I can show this being flipped. I see a camera getting closer. Let’s see if we can see anything here. It will be more visible on screen. Well, I know why that doesn’t look so hot. I’m doing it upside down. Although it doesn’t make a heck of a lot of difference in a lot of my imagery. There’s a figure in there you can see vaguely running around. Now, some of this color stuff is just crayon, but some of it is stuff that comes right out of the Xerox machine.

How do you tell the difference? Show me a Xerox.

I’d like to show you one. I’m struggling here because I don’t think this sequence has many. This is mainly crayon. Darn it.

Not even a Zerox.

There’s just a bit in a piece here, but this really won’t come across.

How does it transfer to that card?

That transfers by using a pair of scissors and rubber cement, which is the title of the film.

Then we have a rationale for Rubber Cement.

We do. I don’t really need much to title films.

Do you like the smell of rubber cement?

Oh, are you one of those too? A sniffer?

I don’t sniff it much. But as a child I used it, it’s a memory from a long time ago.

As a child I used to build model airplanes and get high on that dope, and my father would call me from upstairs. “It’s 11:30, it’s time to come to bed now.” I’d be down there, high as a kite, without knowing of course what was happening. [Laughs]

[Laughs] I think we should act responsibly to the audience. I hope there’s nobody that’s eleven years old who’s watching this up this late, watching it. But it isn’t a good idea to sniff it. I mean, it probably does give you some brain damage.

Probably. It probably does terrible things. I think it makes your hair fall out.

Well, it didn’t make yours fall out.

No, I didn’t sniff very much of it.

No, it isn’t a good idea to sniff glue. There’s been some real tragedy as a result of that. But the smell of glue is something that I, as a filmmaker and you as a filmmaker, are entirely familiar with.

The smell of editing cement does mean a lot of work to me usually. Because that’s when you’re cutting negative. Rubber cement… I think it’s just a nice word, don’t you think? Or a phrase or whatever it is.

Yes, it goes very trippingly on the tongue.

I mean, rubber and cement, they don’t really go together.

It’s another one of your oppositions.

Another one of my oppositions.

Let’s see Rubber Cement. You’ve even called it RC. Then we’ll come back and we’ll talk about it a little bit.

[Screening of Rubber Cement, 1976]

I don’t think, in this short opportunity we have to talk, that we should let it go by without mentioning at least one of the devices you’re using in this film of a window effect that kind of intensifies certain parts of the frame. I think it is a very strong characteristic of the film. I wonder if you could just comment on it a little bit.

OK, that rectangle, I think, is what you’re talking about.

That’s moving around in the frame.

That is in effect a window, holes cut in cards that obscure the cards underneath. You caught me off base here. I brought in all these images and I don’t have any of that. The way it works is that there’s a card with a rectangle covering an image. The rectangle itself, you can see through that window and see the image underneath. Shoot one frame of that, take that mask away and shoot one frame of the whole image that’s under it. Now that rectangle has been cut out of successive cards and gradually moves and changes size and so forth, so eventually it scans a whole series, every other frame of other images that themselves are changing in shape and so forth. So, what it does is give particular attention to different areas.

It looks like it’s sort of magnifying or intensifying.

Really what you’re seeing is one area through that window of the card of the underneath image. You’re seeing that twice as long as you’re seeing the rest of the image.

It multiplies the effect.

Yes, it’s burned into your retina that much longer. It takes on the feeling of magnifying something, but it isn’t. It’s just intensifying. The duration is longer.

Do you have any words to say to young animators or even middle-aged animators?

[Laughs] Take heart is what I could say.

Keep cutting up.

Or I could say, wait till I’m through, you know? [Laughs] But no, I think there are a lot of people getting back into animation. For a long time, the normal business of animation got to be so expensive that it just wasn’t being done anymore. It went very commercial in terms of inspiration and aesthetic. But now there’s a whole breed of independent filmmakers, of course, some of whom are interested in animation and they’re going about it very directly the way I do. As though they were making paintings, they’re making films.

It’s not an easy life, though. I mean, it’s not even a very financially secure life yet.

I guess not. I mean, there are some doing other things on the side. But if the need is there, the means are there now. The whole concept of slickness versus expression is getting cleared up. There’s no confusion of the two things anymore. By more is less, less is more, and cutting corners and simplifying, maybe the whole thing is getting improved in a way.

We’ve been trying to compress the work of Robert Breer into about ninety minutes, eighty minutes of program time. We’ve seen films of his made over the last twenty years. We’ve seen sculptures which are creeping around on the table in front of us. He’s an artist in many senses of the word, a sculptor, a graphic artist, a filmmaker. He’s a man whose life is totally dedicated to communication of this kind. If any of you are interested in how to see more of Robert Bree, what do they do, Robert?

There are several distributors: Museum of Modern Art, Film-Makers Co-op, both in New York City.

With that information and with your having come here, let me thank you very much, Robert.

Images from Screening Room: Robert Breer (Robert Gardner, 1976)

With the courtesy of Adele Pressman

Milestones: Robert Breer takes place on Monday 2 October 2023 at 20:00 in Art Cinema OFFoff, Ghent. You can find more information on the event here.