Tattooed Reality

Zéro de conduite and L’Atalante by Jean Vigo

In the coming months, Sabzian will publish a dozen new translations of the work of the German film critic Frieda Grafe, the “queen of German film criticism”. Frieda Grafe (1934-2002) started her career in 1962 at the monthly Filmkritik, the flagship of the burgeoning German film criticism at the time. She would publish 120 pieces there. Later, from the early 1970s, Grafe mainly published in the weekly Die Zeit and the daily Süddeutsche Zeitung. She collaborated on monographs on Fritz Lang, F. W. Murnau and Ernst Lubitsch, and translated books by and about Alfred Hitchcock, François Truffaut, Éric Rohmer, Jean-Luc Godard and Jean Renoir. She did this partly together with her husband Enno Patalas, himself one of the most important German film historians and critics of the 20th century, founder-editor of Filmkritik and for a while director of the Munich Film Museum.

Grafe aptly called her reviews “described films” because she concentrated on making her way of looking at films comprehensible and vivid to the reader. Her pieces tried to unfold the world of a film for the reader, to make it transparent. “I try to reconstruct the general colour of a film for the readers from my impressions and insights in order to lead them to conclusions or assumptions of their own.”

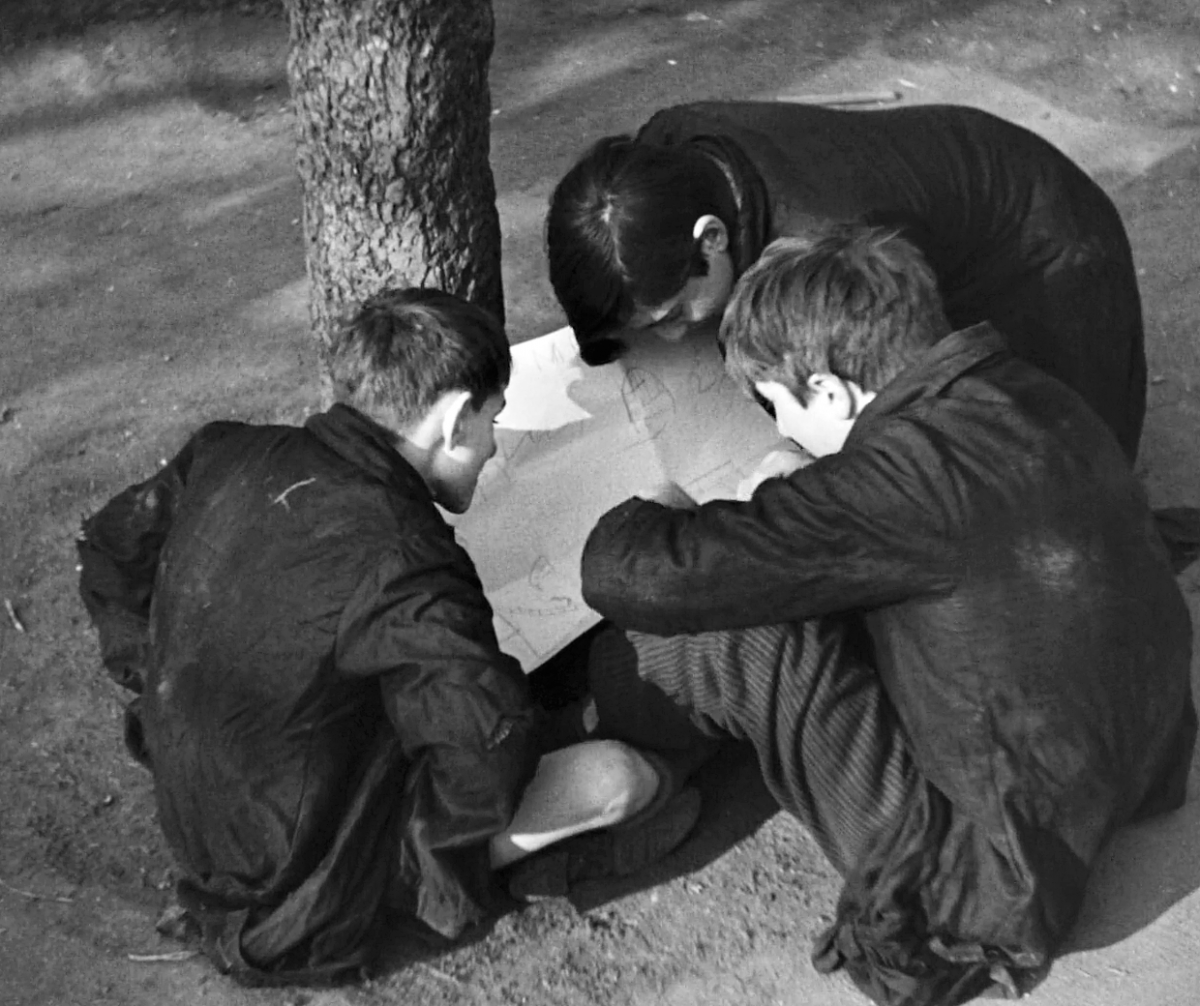

In one programme almost an entire oeuvre. Zéro de conduite, the student revolt, is the better known. From 1933 to 1945, the film was banned; the censor had a fine nose. “A society whose lack of self-consciousness disgusts you, which simply makes you want to look for a revolutionary solution.” Vigo only made political films, though not films in which the political floats to the surface like an indigestible layer of fat.

L’Atalante is a deathbed film, but not a legacy of old age. Vigo was twenty-nine when he died in 1934. Keeping that in mind helps to understand the film. It opens our eyes to its creative contradictions, to its positive negativity. So much hope, so much vitality from someone who is dying! It is not a poetic love story, the ending not a happy ending that smoothes out antagonisms. It is definitely heartbreaking. Even two who love each other will always remain two. Homogenous unity: a bland delusion. But they can certainly become inseparable. You see it right at the beginning of the film, at the wedding. The bride Juliette is all white and her husband Jean black. She runs away from him, following her dreams – Paris. Life on his barge was too confining for her. She returns and finds her dream where it always was. She had not recognised the heaven on earth, the heaven on water, the heaven in the water.

Like puppets – like Chaplin and Paulette Goddard in Modern Times – Jean and Juliette walk from the church down to their barge at the beginning of the film so fast that the wedding guests, who look rather funeral-like, are left far behind. The two of them scurry through the narrow village streets, and then the topography becomes confusing. As if they went across everything. They appear at the top right of the image and disappear down the left-hand side by the river. Jean throws off his party clothes, a cry of joy, his cap flying into the air. The Atalante departs. The wedding guests perplexed on the riverbank.

This first sequence is the path to another rhythm, to a new life, life on the water. “Our senses are not keen enough to see the flow of events; we need forms because we cannot grasp the subtlety of absolute movement.”

Vigo’s films belong to surrealism. Not the Breton school with its suridealism, its amour fou and, for all that, its paternalism. Vigo is one of the “enemies from within”, Bataille, Artaud, life above form, eroticism, the hollowed-out subject. The destruction of the social superstructure becomes the basis of all revolutionary action.

Vigo’s films are porous, Siegfried Kracauer wrote. That is a right word, because it touches different suiting definitions so exactly. L’Atalante is porous, the space depicted never gives a continuous impression. A maze of cabins in the ship’s hull, people emerging from bunks or disappearing into them, Jean crawling on all fours over the covered ship’s hold as if over a globe, the mist dissolving people, Jean finding the image of his beloved in the water below.

“Porous” also evokes the skin. Eroticism flows through the entire film. It never arises only from the relationship between two, it is anarchically pregenital. You feel it rise and fall. After their wedding night, Juliette climbs up, where she is met by her “family”: by Jean, by an adolescent cabin boy and by the boatswain, Père Jules – a false father who has nothing of a father but the name. As if blinded by the sun, Juliette puts her hand over her eyes so as not to show the happiness on her face.

Actually, Père Jules (Michel Simon) is always the centre of the film. A porous film should be thought of as a film with many centres. Père Jules is the driving force of the film, his faltering gait, his fully inarticulate speech, his unpredictable reactions. Through him, you understand how reality and fiction relate to each other in Vigo’s film. The fiction, the story, is just a momentary version of a reality in motion: traces scratched into living skin.

Père Jules keeps the hands of a deceased friend in a preserving jar in his dilapidated cabin, which is full of monstrous souvenirs from all the world’s ports. Juliette is entranced by all these wonders. So is Père Jules, when she tries to divide his matted hair into a parting: “Huh, how beautiful!” The intelligent censor had discovered a dangerous point in this film too. He cut the shot in which Père Jules sticks a cigarette into his navel, which also serves as the mouth of a tattooed woman.

Originally published as ‘Tätowierte Realität. Zero de conduite und L’Atalante von Jean Vigo’ in the Süddeutsche Zeitung, 1973. © Brinkmann & Bose Publisher Berlin, Germany

Image (1) from Zéro de conduite: Jeunes diables au collège (Jean Vigo, 1933)

Images (2), (3) and (4) from L’Atalante (Jean Vigo, 1934)