Toward a Social Cinema

Presentation of À propos de Nice

Lecture by Jean Vigo at the Vieux-Colombier Theater in Paris, on June 14, 1930, on the occasion of the second screening of the film.

You’re right if you don’t think that we’re going to discover America together. I say this to indicate right away the precise import of the words on the scrap of paper you have been given as a promise of more to come.

I’m not concerned today with revealing what social cinema is, no more than I am in strangling it with a formula. Rather, I’m trying to arouse your latent need to more often see good films – filmmakers, please excuse me for the pleonasm – dealing with society and its relationships with individuals and things.

Because, you see, the cinema suffers more from flawed thinking than from a total absence of thought.

At the cinema we treat our minds with a refinement that the Chinese usually reserve for their feet.

On the pretext that the cinema was born yesterday, we speak babytalk, like a daddy who babbles to his darling so that his little babe-in-arms can better understand him.

A camera, after all, is not a pump for creating vacuums.

To aim toward a social cinema would be to consent to work a mine of subjects that reality ceaselessly renews.

It would be to liberate oneself from the two pairs of lips that take 3,000 meters to come together and almost as long to come unstuck.

It would be to avoid the overly artistic subtlety of a pure cinema which contemplates its super-navel from one angle, then from yet another angle, always another angle, a super-angle; that’s technique for technique’s sake.

It would be to dispense with knowing whether the cinema should be silent a priori, or as sonorous as an empty jug, or as 100 percent talking as our war veterans, or in three dimensional relief, in color, with smells, etc.

For, to take another field, why don’t we demand that an author tell us if he used a goose quill or a fountain pen to write his latest novel?

These devices are really no more than fairground trinkets.

Besides, the cinema is governed by the laws of the fairground.

To aim at a social cinema would simply be to agree to say something and to stimulate echoes other than those created by the belches of ladies and gentlemen who come to the cinema to aid their digestion.

And by doing so, we will perhaps avoid the magisterial spanking that M. Georges Duhamel1 administers to us in public.

Today, I would have liked to show you Un chien andalou which, though an interior drama developed as a poem, nevertheless presents, in my view, all the qualities of a film whose subject has social implications.

M. Luis Buñuel was opposed to its screening, and for these very reasons, I am forced to project À propos de Nice for you and to present it to you myself.

I am sorry, for Un chien andalou is a major work in every aspect: the assurance of its direction, the artfulness of its lighting, its perfect knowledge of visual and conceptual associations, its sure dream logic, its admirable confrontation between the subconscious and the rational.

Above all I am sorry because, from a social point of view, Un chien andalou is both an accurate and a courageous film.

Incidentally, I would like to make the point that it is a quite rare kind of film.

I have met M. Buñuel only once and then for only ten minutes. We didn’t discuss the scenario of Un chien andalou. I can therefore speak about it to you all the more freely. Obviously, my comments are personal. Possibly I will get near the truth; without any doubt, I will utter some absurdities.

In order to understand the significance of the film’s title, one must remember that M. Buñuel is Spanish.

An Andalusian dog howls – who then is dead?

Our listlessness, which makes us accept all the horrors men have committed on earth, is put to a severe test when we can’t bear the sight of a woman’s eye cut in two by a razor on the screen. Is it more dreadful than the sight of a cloud veiling a full moon?

Such is the prologue: I must say that it cannot leave us indifferent. It guarantees that, during this film, we will have to watch with something different than our everyday eyes, if I may put it this way.

Throughout the film we are held in the same grip.

From the very first image, we can see in the face of an overgrown child riding down the street on a bicycle without touching the handlebars, hands on his thighs, covered with white frills like so many wings, we can see, I repeat, our ingenuousness that turns to cowardice in contact with a world that we accept (one gets the world one deserves), this world of exaggerated prejudices, of self-denials, and of pathetically romanticized regrets.

M. Buñuel is a fine swordsman who disdains stabbing us in the back.

A kick in the pants to macabre ceremonies, to the final laying out of a being who is no longer there, who is nothing more than a dust-filled hollow on a bed.

A kick in the pants to those who have sullied love by resorting to rape.

A kick in the pants to sadism, of which gawking is its most disguised form.

And let us pluck a little at the reins of the morality with which we harness ourselves. Let’s see a bit of what lies at its foundation.

A cork – here, at least, is a weighty argument.

A bowler hat – the wretched bourgeoisie.

Two brothers of the École chrétienne – poor Christ!2

Two grand pianos crammed with carrion and excrement – our impoverished sentimentality.

Finally, the donkey in close-up; we were expecting it.

M. Buñuel is terrible.

Shame on those who kill in puberty what they could have been, who look for it in the forests and along the beaches where the sea casts up our memories and regrets until they wither away with the coming of Spring.

Cave canem... beware of the dog – it bites.

I say all this to avoid too dry an analysis, image by image, which is in any case something impossible for a good film whose savage poetry must be respected – and only in the hope of stimulating your desire to see or to see again Un chien andalou.

To aim at a social cinema is therefore simply to underwrite a cinema that deals with provocative subjects, subjects that cut into flesh.

But I want to talk with you more precisely about a social cinema, one that I am closer to: a social documentary or, more precisely, a documented point of view.

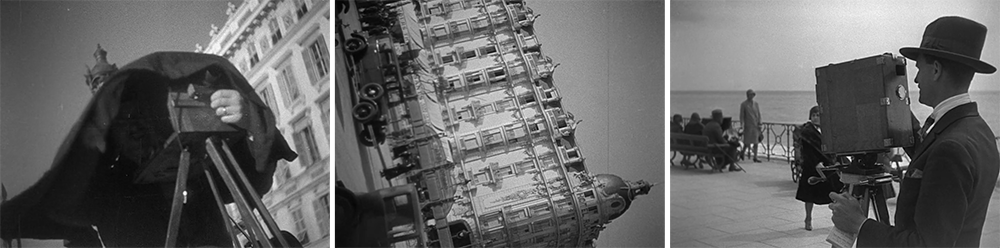

In the realm to be explored, the camera is king or, at least, President of the Republic.

I don’t know if the result will be a work of art, but I am sure that it will be cinematic – cinematic in the sense that no other art form, no other science could take its place.

Anyone making social documentaries must be slim enough to slip through the keyhole of a Romanian lock and be able to catch Prince Carol jumping out of bed in his shirt tails, assuming, that is, that one thinks such a spectacle worthy of interest. The person who makes social documentaries must be a fellow small enough to fit under the chair of a croupier, that great god of the Monte Carlo casino – and believe me, that’s not easy!

A social documentary is distinguished from an ordinary documentary and weekly newsreels by the viewpoint that the author clearly supports in it.

This kind of social documentary demands that one take a position because it dots the i’s.

If it doesn’t interest an artist, at least a man will find it compelling. And that’s worth at least as much.

The camera is aimed at what must be considered a document, which will be treated as a document during the editing.

Obviously, self-conscious acting cannot be tolerated. The subject must be taken unawares by the camera, or else one must surrender all claims to any “documentary” value such a cinema possesses.

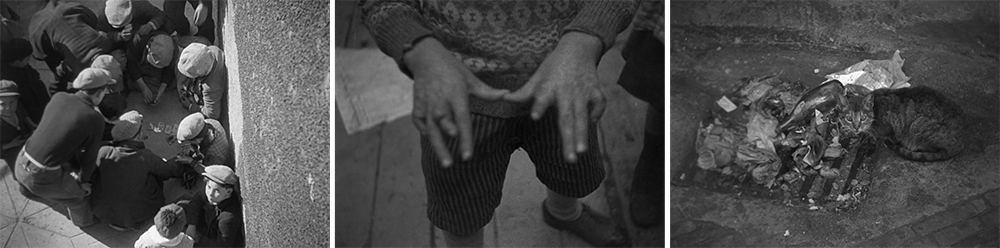

And the goal will be attained if one succeeds in revealing the hidden reason behind a gesture, in extracting from a banal person chosen at random his interior beauty or caricature, if one succeeds in revealing the spirit of a collectivity through one of its purely physical manifestations.

And all this with such force that from now on the world, which we, indifferent, have heretofore passed by, will be presented to us, in spite of itself, over and above its outward appearances. A social documentary should open our eyes.3

À propos de Nice is only a simple rough draft of such a cinema.

In this film, by means of a city whose events are significant, we witness a certain world on trial.

In fact, no sooner is the atmosphere of Nice and the kind of life one leads there – and elsewhere, alas! – evoked than the film moves to generalize from the gross festivities by situating them under the sign of the grotesque, of the flesh and of death; these are the last convulsions of a society so little conscious of itself that it is enough to make you so nauseated that you will become an accomplice to a revolutionary solution.

- 1Georges Duhamel (1884-1966), one of the founders of L’Abbaye de Créteil, French author, physician and moralist. Duhamel had just published Scènes de la vie future (1930), in which he ridiculed anyone foolish enough to work in the cinema.

- 2The École chrétienne is a charitable religious institution devoted to educating the children of the poor.

- 3Vigo uses the phrase ‘dessiller les yeux’, which means not only ‘to open someone’s eyes (to facts)’, but also ‘to undeceive someone’.

This translation was first published in English in Millennium Film Journal, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Winter 1977-78): 21-24. The translator revised it for this publication.

Images from À propos de Nice (Jean Vigo & Boris Kaufman, 1930)