The Dark Side of the Moon

The Global Media Crisis

The following statement is the first of two parts. It is specifically concerned with the language form of the mass audiovisual media – i.e., the use by the MAVM of a repetitive, standardized structure, and abbreviated time and space, to control the audience. I am concentrating on this little debated aspect of the media first, because it has played an essential role in developing the narrative structure which has been in place, and enforced, since the birth of the cinema. It is my contention that had we acknowledged and critically confronted this Monoform language decades ago, we would probably not be where we are today – in the grip of the relentlessly abbreviated MAVM and so-called ‘social media’.

Part II will discuss aspects of the new technology (Facebook, Twitter, etc.) and their subterranean relationship – in combination with the MAVM – to the increasing acceptance of global authoritarianism and the rise of populism. Part II will also introduce some thoughts on the role of the print media in the growing crisis, and critical research by the French author Juliette Volcler on the growing (mis) use of SOUND, including by the mass media. It will also present alternative media education principles and practices, and a number of references to supportive voices for my own work over the past 50 years.

By the ‘global media crisis’ I mean a composite of issues relating to the standardisation of the mass audiovisual media (MAVM), which began early in the 20th century with the development of the language form used by Hollywood to narrate and structure cinema films. This language form, which fundamentally has never changed, was adopted by international TV in the 1950s and is now taken on by the internet, Youtube, social media, etc.

In the mid-1970s, during summer courses at Columbia University in New York City, a group of students and I studied and specified the characteristics of this uniform and repetitive language form which frames almost the entire output of the MAVM. We called it the Monoform.

With few exceptions, the Hollywood Monoform has been adopted by virtually all creators of commercial films, most documentary films, and by all aspects of television production including news broadcasting. This global adoption of one language form - in effect a standardisation of the mass audiovisual media – is a central issue of the media crisis. It means, for example, that a documentary film can basically have much the same form and narrative structure as a Netflix drama series.

The Monoform is like a time-and-space grid clamped down over all the various elements of any film or TV programme. This tightly constructed grid promotes a rapid flow of changing images or scenes, constant camera movement, and dense layers of sound. A principal characteristic of the Monoform is its rapid, agitated editing, which can be identified by timing the interval between edited shots (or cuts), and dividing the number of seconds into the overall length of the film. In the 1970s, the Average Shot Length for a cinema film (or documentary, or TV newsbroadcast) was approximately 6-7 seconds, today the commercial Average Shot Length is probably circa 3-4 seconds, and decreasing.1

It is my belief that the excessive demands of these flashing images on our emotional and intellectual responses can lead to blurred distinctions between themes, and to a confusion in selecting and prioritising our reactions (e.g., to the news scene of a bleeding body in a bombed area in Syria, which is followed by a commercial message, and sooner or later, by the image of a similarly bleeding body in a film or TV drama, etc.).

Despite academic claims that audiences have become ‘media literate’, the standardised rate at which audiovisual information is delivered is probably far too swift to be properly managed by the brain, which has to digest and process the rapid and continual change of visual (and audio) information from one scene to the next, and to the next, and to the next, and so on. I can anticipate a negative response from the media education sector to this analysis on the grounds that it is ‘arrogant’ to presume that audiences cannot understand or decipher the workings of the Monoform (even if they believe such a thing exists). But the fact that viewers ingest the Monoform every day is not a precursor to understanding how (or why) it functions in the way that it does. The form itself may neutralise any understanding of how it works, including by habituating us to its presentation, not to mention its more subterranean and less perceivable properties. As this subject is never raised by the MAVM, and is too rarely discussed by media educators, there is hardly a wealth of analysis or information for people to rely on.

Media scholars also claim that this fragmented message process is beneficial, because – in true postmodern tradition – it allows us to interpret audiovisual material in multiple different ways. But without a public forum or collective discussion, these fragmented individual reactions are not likely to deliver us out of our present global predicament. Can we look at the political, social and environmental chaos of our world, and not wonder if the most powerful forms of communication ever devised by man might play a role in what is happening?

The other day there was a public meeting in our village in France, on the theme “Comment s’adapter face au changement climatique” (How to adapt to climate change). Notably, the thrust of the talk was adaptation. Insulating a roof to prevent heat loss is important, but it is not an analysis of what has caused climate change, or how to oppose it, or the role played by the MAVM in fostering it. In precisely the same way, audiences, most media professionals, and educators all over the world have adapted to the Monoform and its effects – with little discussion, query or challenge.

Generally, of course, we can only speculate on the long-term psychological and environmental effects of the sustained use of the Monoform MAVM. But amongst those that have come to light, as early as in the 1990s, is the fact that there has been a severe drop in the attention span of children (and now most adults) over the past 3-4 decades.

Significantly, we have done nothing to try to reverse this attention span problem, nor do we even discuss its possible sources. Why is this? I think it bears repeating that this may be due to the fact that the language of the Monoform Mass Media has itself neutralised our very awareness of its effects, deprioritising or even blocking any attempt to challenge it – let alone change it.

In considering the problem of standardisation, it is important to keep in mind that the Monoform is just one of numerous audiovisual language forms and processes that are available to the mass media and to the individual filmmaker. Cinema, TV popular culture, news programmes and documentaries could allow multiple variations in the use of time, space and rhythm. The potential for variety is borne out by the various alternative narrative, documentary, and experimental films that have been produced during the relatively brief history of the cinema. Many of them do not use the Monoform to relate to their audiences. Unfortunately, given the crushing weight of the contemporary MAVM, most alternative works are rarely seen other than at ‘specialist’ film festivals or film courses.

This in turn means that the MAVM continue to prevent any serious professional debate, or open discussion in public, as to the ways in which we could learn, including from alternative works, how to break out of the standard media practices and unseal the stultifying existing relationship between the MAVM and the audience.

We can extrapolate from all of this that the Monoform is not only a particular language form, but that it is also the entire ethos behind the approach of the MAVM towards mass communication and the relationship with the public. The very word ‘communication’ is a misnomer to start with, since a genuine two-way communication does not exist in the way that the MAVM functions - either with respect to their own fellow professionals, or regarding the public.

As far as the internal environment of the MAVM is concerned, their members have created and accepted their own professional practices (‘demons’ I prefer to call them). These include the demeaning exercise called ‘pitching’, in which filmmakers seek funding for their TV or film projects by standing before their fellow professionals and proposing a programme idea in approximately six minutes. It is visibly apparent that a professional practice like this reproduces the ethos of the Monoform. Six minutes to evaluate, to accept or reject, the theme of a documentary film?

There is also the TV scheduling practice known as the ‘universal clock’, in which a programme hour is in fact 52 minutes (or less), in order to allow time for commercial advertising. This means that those TV programmes and films that can be explained in six minutes are then edited to a uniform length of precisely 52 minutes, irrespective of the demand or importance of their theme. The ‘universal clock’ allows TV stations to replace programmes (they should be called ‘modules’) at the last minute, by others of the same length.

This Kafkaesque situation is far worse in its implications for the public. I have already described how the mass audiovisual language form is usually constructed. But what is the ideology that supports it? Perhaps we can’t give it a precise name, but we can certainly describe its intent, which is the opposite of any form of genuine two-way communication. The aim of the MAVM is to create a non-stop stream of impact points (surprises as one filmmaker called them) that will prevent viewers from being bored, and – crucially important – from experiencing a variety of reactions, let alone have time to reflect upon or query what is entering their subconscious. Of course, human nature doesn’t always work this way, but that does not alter the intent of the professional Monoform creators.

*

The MAVM are not alone in creating and maintaining the crisis described here. Much of the world of Media Education – including Media, Journalism and Culture Studies, Cinema and TV Studies, teacher training courses, national film schools, universities – is now complicitous with the MAVM in constraining the relationship between the audiovisual media and the public.

Over the years most MAVM and media education professionals have enforced the Monoform as the declared sine qua non for the success of any cinema film, TV programme or documentary. ‘Success’ here does not mean conveying audiovisual messages in such a manner that the audience is participating in a pluralistic manner in the process. On the contrary, for many professionals, ‘success’ means creating a captive audience that passively allows hierarchical audiovisual messages – overt and covert – to penetrate deep into its subconscious. The potential consequences inherent in using the MAVM are rarely discussed by media professionals, and hardly more so within the corridors of most contemporary media education institutions. Discussion of the topic at the tertiary level is usually subsumed by the prioritised instruction of the ways and techniques – the “skills” or “standard practices’’ - of the Monoform.

For example, I once asked a professor of media studies at a university in the south of France about critical teaching, and the Monoform, in their courses. He hesitated, and then said, “Well, we do teach them standard media practices”. I asked if he meant the Monoform… “No, no!” he said hurriedly, and then proceeded to reassure me that he meant teaching the students practical things like which buttons to press on the editing machines. He avoided telling me what the students were taught once they knew which buttons to press, but he did clarify the position of his media department: “We do allow the students to make their own alternative films, but of course we know that these students will never enter the professional media …”

On record is the following statement made by a TV executive: “We’re ahead of the game because we’ve had to do it for so long... you build in the customisation right from the word ‘go’ – almost the moment that the pencil touches the paper pad... there are film-makers who quite justifiably say: ‘This is my work and I want it to stay as it is’. That’s their right and we respect that. Those are the films we don’t buy and those are the films we don’t transmit.”2

What is striking here (apart from the irony that the speaker was an executive at the Discovery Channel!) is not only the fact that the media education sector knows, a priori, that the MAVM will generally avoid or suppress alternative work, but also the implication that educators appear to be doing little, if anything, to change – let alone challenge – this situation.

It must be despairing to those students with different visions of film and the documentary form, to realise that in reality they have been written off by their teachers, and that they cannot expect professional support once they leave the tertiary sector, simply because they have chosen non-standard forms of audiovisual expression.

This raises an essential question: what exactly is the role of a school or university media course? Is it to provide authoritarian and narrowly directed professional training as a form of apprenticeship prior to entering a particular profession or industry? Or is education, in the broadest sense, meant to encourage people to examine the world around them, and to offer a variety of views and alternative possibilties - along with the freedom to develop their own critical insights and their own creative talents?

The answer to this question is, sadly, all too obvious. I have recently begun to research courses listed on the websites of UK universities offering media education, and of the dozen that I have thus far checked, nearly all appear to teach the “standard practices” of the MAVM to media, film, and journalism students – the idea being, presumably, that they will provide ‘fresh blood’ for the machinery of the mass communication industry. Disturbingly forthright in their publicity, most of these universities offer “out of the box” and “cutting edge teaching”, “critical training” and promises of “job placement” within the mass media.

I suspect an obfuscation of the terms of reference here, including of the word ‘critical’. ‘Out of the box’ actually means jumping out of one box into another. Not discussing the media crisis or the problems inherent in the standardisation of the MAVM will always affect students, and in turn the viewing / listening / reading public.

One needs to be wary of promises such as, “you’ll be taught by leading names in media, communications and cultural studies”. Many of these teachers and media workers have themselves grown up as children of the Monoform, often with no genuinely critical media education, with the result that most of them view the standardised media as being a ‘normal’ part of the culture, and thus beyond any holistic challenge.

One UK university writes: “Film is the dominant art form of the 21st century, both reflecting and influencing society and culture. Learning to read films as more than a form of entertainment will develop your skills in analysis and interpretation.” But further down one reads that this same university has spent an incredible sum of money (enough to feed, clothe and shelter thousands of displaced persons) on “investment in college facilities to make sure students have access to the most up-to-date, industry-standard equipment. Our strong industry links with employers means our students are now expected to secure work placements as part of their wider learning...”

I had hoped that colleges of art might somehow be an oasis in this depressing scene, but in my initial research I immediately came across a college of art in the UK which offers media training courses and uses a local video production company to provide equipment and training. The promo video produced by this company for the college is almost a satire of the biff-bang-wallop genre, with scenes flashing by in less than a few seconds. Accompanied by jarring music and gymnastic camera movements, it is practically a do-it-yourself exercise in producing the Monoform.

Media Popular Culture is another broad front embracing non-critical media education. By the early 1980s, teaching popular culture had become almost as big a business as the MPC itself. The propaganda in this case included an emphasis on the alleged ‘democratic values’ inherent in popular culture (soap operas, crime series, etc.) by nature of its ‘street level’ commonly shared appeal.

Accompanying the propaganda was the barely veiled threat by certain academics that opposition to media popular culture was ‘middle class and elitist’. This form of rarely challenged marginalisation effectively became a serious obstacle to genuinely critical media education. And thirty years later we have very little critical discussion about the authoritarian nature and values of popular media ‘standard practices’ - including regarding their role in embedding the Monoform deeply into the MAVM culture, and thereby delivering us into the arms of commercial interests and the dictates of the State.

Why are the media departments of many tertiary institutions complicitous in the media crisis, why do they behave like branches of the MAVM rather than independent places of learning?

I understand the need for job placement in this day and age - but job placement into what, and with what end in view? I have often heard media students, who have worked in the MAVM for a year or two, say that they had known of the difficulties in their profession, and that they had planned to change things, to develop their own ideas once they entered the mainstream. It took about a year or so for reality to hit home...

Why do so many universities compound the problem by denying their students a more holistic and critical evaluation of the MAVM and their role in society?

Non-critical media teaching is now spreading like wildfire to the secondary school sector. Various countries use their education systems to impart to their students the ‘skills’ necessary to shoot films and videos (even if these students have no intention of joining the MAVM), thereby utilising a classic method for teaching young people to accept the consumerist and fragmented popular culture.

As an example of the general direction of global media teaching, I quote from a promotional blurb about a programme in the French national education system called CLEMI, which focuses on drawing secondary school pupils into the web of the media popular culture, and professional skills: “Each year, thousands of students take the floor, and, with the help of their teachers, produce print and online newspapers, radio programs and videos. School media projects enable young people to acquire skills far beyond traditional knowledge.” There is no prize for guessing what skills and world views are involved here, and what role the Monoform plays therein.

I can imagine a rebuttal from this sector claiming that youngsters are being taught to be ‘media literate’, but as this pedagogy seems to be based on teaching how to ‘appreciate the aesthetic pleasures’ of the cinema, it is doubtful that there is much critical evaluation of the MAVM. I wrote to several local French schools which promote the CLEMI programme, to ask if they discuss the standardisation of the MAVM, but had no reply even to repeated letters.

Many media and education professionals deny the existence of one standardised, controlling audiovisual form. Indeed, most actually seem to be unaware of the role played by a structural language form when they produce (or teach) cinema and TV, and appear to have great difficulty in accepting that the way in which a message is shaped and delivered directly affects the way in which the message is received and perceived.

If, for example, I am at a public meeting, and I have a message to pass to someone in the audience facing me, I do have choices. I can speak directly from the platform. Or I can write the message on a piece of paper, put it into a steel film can, and hurl the can at the victim. Conversely, I can sit beside the person, and quietly give him/her the same message. Even better, I can engage in a dialogue. Each method delivers the message, but each method has an entirely different meaning for the participant who receives and accepts said message. And, yes, there has been a choice.

Yet we who work with the MAVM – especially those of us who produce, direct, edit, or teach – seem mostly unable to apply this logic to how we structure audiovisual messages, to grasp that how we organise filmic time, space and rhythm can directly affect how the viewer perceives the content, or to imagine that there are numerous possibilities for variations in this process. And so, media teachers continue to teach media students - and even more disturbingly, secondary school pupils - the ‘skills’ that are necessary for the ‘standard practice’ of making a film or a video.

Apart from the MAVM’s likely role in fostering consumerism, climate change, sexism, aggression, fear of the other, anti-immigrant sentiments, privatisation instead of collectivity, etc., and apart from the destructive role that enforcement of media standard practices has played on the creative development of the cinema and television, we are also continuing to deny any public or pedagogical debate about the possibility of democratic choice in how the general community receives audiovisual material. We deny the public any form of pluralistic role in the creation and reception of the MAVM. Clearly we professionals don’t want this - we want the public at a safe arm’s length, for they frighten us. Therefore we use a language form calculated to deny time and space for reflection, let alone interrogation as to what viewers are watching and listening to.

Given this situation, trying to find a place of learning without the industry directed traps that I have described here requires careful navigating for a non-authoritarian and more open ended form of media education. It does still exist. I located an internet site of an English university that states: “We live in a multicultural society and media saturated world. Most of what we know about the world comes to us through the media – but how much do we know about the media? Whether as sources of information, producers of entertainment or modes of creative self expression, contemporary media are all too seldom subject to intense scrutiny and critical interrogation, except during feverish moments of scandal, crisis or panic.”

This university is suggesting that students probe these issues by fusing sociology, cultural, and media studies; indeed the course is offered from within the Department of Sociology. The website continues: “You will be encouraged to reflect critically on the role of popular media in structuring our everyday lives. The course examines the role of media in reproducing, disseminating and challenging hegemonic power relations, as well as thinking through the ways in which genders, sexuality, and ‘race’ are constructed in global media cultures.” “This is not a vocational or practice-based degree. However, it is a degree that will teach you skills in critical thinking, independent research, and analysis highly relevant for development and innovation in the cultural and media sectors.”

I have not attended this course, nor visited this university. I am just very encouraged by what it writes, and by the fact that it is not accompanied by claims of a new multi-million dollar studio or any blandishments to be “out of the box” and at the “cutting edge”.

*

I do understand that the issues I refer to are not black and white. For example, I have noticed new developments creeping into the language form of various narrative feature films in the past decade or so – a willingness to hold the camera on the face of someone during a dialogue scene, an increased complexity of narrative structure, fusing past and present, etc. One cannot say to what degree these sorts of changes are due to an increased critical understanding of the Monoform problem, or simply there as interesting stylistic changes. Repeated use of the latter can of course result in their becoming elements of the Monoform, or, equally possible, a new revised Monoform.

Even more complex is the fact that the use of the Monoform in and of itself cannot, and does not, always override the value of the theme, or the intensity of the acting, or a particular complex structure. We have all seen films where these elements outweigh the constraints of the Monoform. For example, the other evening my wife Vida and I viewed a film from Iran, entitled Life+1 Day (2016, Saeed Roustayi). Set in present day Tehran, the film represents a family caught up in the problems of poverty, drug addiction, and an arranged marriage that will leave the family even worse off. The ensemble playing was remarkable, and in no way constrained by the Monoform. Of course, the same dynamic effect – the same awareness bought to bear on the suffering caused by poverty – could have been achieved by other language forms, but this does not change the fact that it was very effective as conveyed here by the Monoform. This does not, however, mean that the Monoform functions equally well when applied uniformly to nearly all audiovisual material!

*

I need to draw attention now to another highly problematic aspect of the Monoform - the repression that keeps it in place. The fact that I give examples of the marginalisation of my own work does not – I want to stress – mean that these experiences are unique to myself. But as I do not have access to the life experiences of other filmmakers, I offer a few examples from my own, as evidence of the way in which alternative, critical ideas are discredited and marginalised within the audiovisual media.

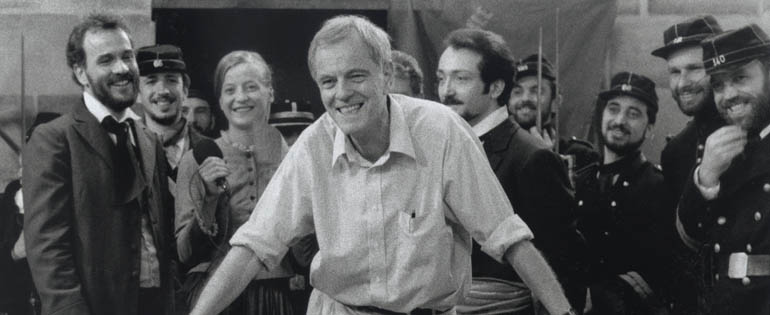

To begin at the beginning of my own story: after an enjoyable period of making amateur films, I went on to train, in the early 1960s, at the BBC. There we were taught that professional ‘objectivity’ was the absolute sine qua non of TV broadcasting. We were informed that if we did not apply this standard, but allowed subjectivity to influence our work, we would have to leave the BBC and “make our name in some other field”(!). The Monoform was obviously never discussed - nor was the lie that there is a ‘neutral’ way of presenting audiovisual information. Although I was unaware, before my time at Columbia University in the mid-1970s, of the problems of the Monoform, and despite the fact that I used this language form liberally to structure my own work, I did try from the outset to subvert the concept of media ‘reality’ and infallibility. I used what I hoped was a visible warning sign (a fake documentary style), and I did express my subjective feelings in my work (regarding the consequences of nuclear war in The War Game, the conformist effects of popular culture in Privilege, the treatment of protesters in Punishment Park, the personal sentiments expressed in Edvard Munch, etc.). But I am not at all sure that these attempts outweigh the perceptual problems inherent in the Monoform as I used it in these and other works prior to the 1980s.

I definitely tried to challenge the standard Monoform structure in my later films, The Journey, The Freethinker, La Commune - but their success or otherwise is not something that I can judge.

The criticism of my films by both the MAVM and a good number of film critics has been non-ending. It began in the 1960s with the banning of The War Game and with deliberate attempts by the BBC to blacken my name at that time.3 The marginalisation in the UK escalated with vehement attacks by the British press on my first feature film Privilege, and with the TV banning of Punishment Park in the United States (which continues to this day); it included the blocking of my proposals for TV drama-documentaries on the danger of nuclear meltdown (I was told that this could never happen); it persevered with the refusal by the Franco-German TV station ARTE (co-producer of the film) to screen La Commune at a normal hour, followed later by the destruction of the film negative by the original producer.4 etc.

Actions such as these have been interwoven with the long running marginalisation by media educators of my critical work on the Monoform, and by schools that have not permitted me to work with their students. On the positive side, over the past years I have been much supported by a number of universities and colleges where I have held critical media courses (Columbia in NYC; Utica College, New York; Wayne State University, Detroit; Monash in Melbourne, Australia, University of Auckland, N.Z., the Red Cross and Biskops-Arno Folk High Schools, Sweden; etc.). But I have never been accepted into the more general university milieu on a longer term basis to develop courses in critical media education.

A particularly unpleasant aspect to the marginalising process has been the ad hominem nature of the attacks on my work – whether from my own profession or in the field of media education. Notable in more recent years is the fact that even an acknowledgement that my films may have some validity is ‘balanced’ by an attack, often vindictive, on me personally.

For example, in Camera Historica (2008), a book on the work of various filmmakers, the author Antoine de Baecque, a French professor of FilmStudies and the editor in chief of the French magazine Cahiers du Cinéma, writes: “Scathing accusations against the political and media ‘other’, and permanent suspicion of a conspiracy being fomented against him have come to constitute Peter Watkins’s discourse of martydom. It is part and parcel of his style and method, which can be seen as paranoid... Peter Watkins can be considered both the victim and the perpetrator of his own martyrdom...”. He also writes that I challenge the documentary genre with “insolent and libertarian violence”.

Another example comes from the introduction materials to a conference on my work, organised by the University of Bordeaux III in 2010.5 About a dozen scholars gave papers and spoke seriously about my work on the Monoform at this event. It had been the only such conference on my work, and was therefore very important to me. This did not prevent the two media scholars who organized the conference from writing the following qualification in their introduction: “… as Antoine de Baecque has noted in his book, the man is an immense cinéaste before being a great thinker.”

There is also an article in The Journal of Contemporary History (2006), written by a British professor of Cultural Studies. Throughout his article, The BBC and the Censorship of The War Game (1965), this academic keeps repeating how difficult I was to deal with [well yes, I did resist the banning of the film] with statements such as, “Watkins did himself no favours with his incessant complaints and demands... impatient, opinionated and stubborn.” The professor concludes with the assertion that, “...the decision not to broadcast The War Game, far from being a conspiracy to keep the 'truth' of nuclear warfare from the British public, as Watkins maintained, was instead the result of a range of institutional and cultural factors that caused the BBC to act as it did.”

I don’t know when this professor did his research, but some time later, Professor John Cook, a media scholar at Glasgow Caledonian University, unearthed several BBC memoranda that proved that the BBC had indeed yielded to government pressure to ban The War Game, and that the BBC had lied to the public when it denied this fact in 1966.6

Another aspect of the marginalisation against my work could be called ‘the wipeout’ - rather than name-call, this practice pretends that my films and media critique barely exist. Some months ago, I received an email from a Turkish writer and film enthusiast, who remarked that younger generations are not aware of my work. He also mentioned that he had never seen an article about my work either in Cahiers du Cinéma or the British film magazine Sight and Sound. I have often been told that young people have not heard of my films. I think this is particularly true in my own country, where the status quo cinema organs have conducted a policy of ‘studied avoidance’ regarding my work.7

One last aspect of the media crisis is the international film festival, a phenomenon that I write about in some detail on my website. Suffice it to say here that even the less commercial festivals (e.g., the non-red-carpet variety) invariably find it nearly impossible to break their traditional pattern of mass consumption, in order to allow the public time to discuss what they are seeing. There is even less time for debating the issue of the standardised forms that are flashing before their eyes. I, and those who on occasion have represented my work, have asked festival organizers for a public discussion (not an event curated and controlled by film experts) on the issues raised by my work, but have been denied this possibility. “There is no time”, we are usually told. Nor perhaps the wish.

Be all of this as it may - the problems that have beset my own work are of relevance only if they can help to raise debate on the resistance of the MAVM and the media education sector to breaking out of their standardised practises, and to seriously re-examining the nature of their impact on the public and on students.

The essential challenge is to find ways to encourage people to take up these issues with MAVM and media education professionals, to press for critical debate and democratic change that can lead at least to a genuine CHOICE for the public between the Monoform and alternative, pluralistic media processes. The same goes for what is taught to students and pupils.

Given the difficult reality, I am extremely pleased that the Wolf Kino in Berlin has decided not only to host a retrospective of my work in May and June, 2018, but also to open it up for public discussion on the basis of its relationship to the media crisis I have shared here. On this occasion – there will be time!

- 1See also Barry Salt, Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis (London: Starword, 1983) and Cinemetrics, the film measurement database and study tool programme created by Yuri Tsivian and Gunars Civjans in 2005.

- 2Extract from the documentary film The Universal Clock – The Resistance of Peter Watkins (2001, by Canadian filmmakers Geoff Bowie and Petra Valier)

- 3In December 1966 the BBC stated on the evening news (!) that I had deliberately hidden tripwires in the heather to ensure ‘realism’ when the Highlanders were shot down by the Government army, in my film Culloden. This ‘information’ had not been verified with the cast, and was entirely false.

- 4This episode and other methods of marginalization will be further described in Part 2 of this statement.

- 5L’insurrection médiatique: Médias, histoire et documentaire dans le cinéma de Peter Watkins .

- 6As reported in The Herald, Scotland (June 1, 2015).

- 7Among the UK encyclopedias of the cinema that don’t mention my work: Cinema The Whole Story ed. Philip Kemp (2013); New Biographical Dictionary of Film, David Thomson (1975, reissued 2010); Radio Times (UK) Guide to Films (2016) - the index ends with Punishment Park (1970) ; The Cinema Book (2007); The Oxford History of World Cinema 1996.

On a positive note, I should mention that although the British Film Insititute has played a very ambivalent role regarding my work (including to decline being part of a lecture tour I gave in the UK in 1996), there is now a very positive review by Will Fowler of my work on the BFI website

This text was originally published on Peter Watkins's website.

With thanks to Peter Watkins