“I continue to work. It’s my nature.”

An Interview with Raoul Servais

Belgian filmmaker and animator Raoul Servais died on 17 March 2023 at the age of 94. Servais was born in 1928 in Ostend and studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent. There, he developed his style and experimented with animation techniques. He founded the Animation Film Department there in 1963, the first in Europe, and would teach there for many years. Servais was awarded more than 60 times, including the Golden Palm for Harpya at the 1979 Cannes Film Festival. As recently as October 2022, Servais attended Film Fest Ghent to attend the world premiere of his short film Der lange Kerl. There, he received the Joseph Plateau Honorary Award for his entire oeuvre. On the occasion of his recent passing, Sabzian republishes this interview that Silke Rochtus conducted with “the magician from Ostend” for Panoramic, the monograph published in 2018 as part of the retrospective exhibition around his work at Mu.ZEE in his hometown Ostend.

∗

∗ ∗

The very first box of colour pencils Raoul Servais received as a child made a profound impression on him. Young Raoul considered the act of creating something on paper to be a real miracle. The second experience that marked him was the first time he watched Felix the Cat moving on a silver screen. This sense of marvel and the mystery of what makes an animated film fuelled his passion. Since then, Raoul Servais has continued to discover and produce, search and create. None of his films resemble any of his other work. Technique and style provide endless options for Servais, allowing him to explore the world. The themes and interests that he finds important are key themes in his films, which he constantly revisits.

Silke Rochtus: In 2018, Mu.ZEE will open a permanent exhibition of your works. How do you feel about this?

Raoul Servais: I’m very honoured that a permanent exhibition is dedicated to my work in Ostend. I never expected to see my work exhibited alongside paintings by Ensor and Spilliaert. I admire both these artists very much. Perhaps my ideas about art are much more similar to Spilliaert’s. I like the element of mystery in his work.

You also love the city of Ostend.

I was born in Ostend. I have several good memories of my early childhood there, before the war. At the time, it was a lovely Victorian city, with a lot of unique architecture. I was already intrigued by the cosmopolitan atmosphere as a child. I lived in an old eighteenth-century house on Kapellenstraat with my parents. It used to be a hotel, but we shared it with family members. The large house had a soul of its own, and a mysterious atmosphere because of the many rooms and underground passages.

The discovery of film

Mystery is a frequent theme in your films. You always regarded film as a medium to be discovered. Why the fascination?

My father had a porcelain shop in Kapellenstraat. But his favourite pastime was making home movies. He also had an amazing collection of smallfilm. In those days, they came on 9.5 mm reels. His cabinets were chock-full of films! Unfortunately these were destroyed in 1940 during the war. Every Sunday afternoon, my dad would treat me to a double bill, with a short film, a long film and an animated film. I adored Charlie Chaplin and Felix the Cat. The moving images fascinated me. I wanted to know how non-moving images became a film. When my father was not looking, I would get the reels out of the cabinet and examine them. The cat in the sequential images looked like the same cat, but always slightly different. I soon understood that you needed a lot of drawings to make something move, but nonetheless I was endlessly fascinated by the mystery of movement when my father switched on the projector. It was this mystery that pushed me to become an animated film maker.

Where did you unravel this mystery?

In those days there were no schools to learn the tricks of the trade, nor was there any literature available. I visited animation studios in Paris and Antwerp but they were very secretive about the technique as they feared the competition. They even went so far as to prohibit film technicians from talking to the animation team and vice versa so nobody would know the entire process from A to Z. After a lot of crazy experiments and a lot of tinkering around, I finally figured out how to make my own animated film. I made my very first film, Spokenhistorie, while I was still at school. An excellent lecturer at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts Ghent, called Albert Vermeiren, was aware of my enthusiasm and assisted me. I had no money to buy equipment so he made me a camera using an old cigar box, some Meccano building blocks and an old lens. I made some drawings on the film for this camera, so I could start to experiment. Spokenhistorie was a short film – and a really bad one at that – but it was an animated film!

“Nostalgia is a breeding ground for poetry”

The film that kick-started your career was Havenlichten [Harbour Lights] (1960).

Havenlichten was my first finished product. This experiment taught me everything. I made everything myself, from the script to the drawings and the sound. I spent two years working on just ten minutes. I read an article in the newspaper about a national film festival in Antwerp which is how I decided to submit my film. I saw a lot of really nice animated films there. I thought Havenlichten was terrible, so I had no illusions. Much to my surprise, I was awarded the prize for best animated film. I was ecstatic! The jury said that I still had a lot to learn but they wanted to support me because I was the first artist in Belgium who chose not to follow the Hollywood style.

Can you tell us more about Harbour Lights?

The animation is somewhat clumsy and the sound has plenty of defects but the graphic style was simple and powerful. It tells the story of a defective street lantern, which is about to be scrapped, but which saves a fisherman’s life when the lighthouse falls asleep. I love the sea, but I fear it in equal measure. I cannot live without it. I need to hear it, need to smell the salt air. As a child, I could see the light of the lighthouse from my bedroom window. On stormy nights, I hoped that the fishermen at sea would spot the beams of the lighthouse and would return to port safely. It is this idea that I wanted to express to a certain extent in Harbour Lights.

Your nostalgia for the sea and the port is also palpable in Sirene (1968).

Sirene is also situated in a port city. Large cranes and prehistoric birds are the guardians of a lost world. A fisherman witnesses the idyll between a mermaid and a cabin boy. The film is defined by the two primary colours and emotions: blue stands for romance and sentiment, red for drama. The classic appearance of the human characters and the stylised, geometric surroundings of the cranes, the prehistoric birds and the law enforcement officers create an interesting contrast.

How do you portray the less poetic side in this film?

After a fake investigation, the fisherman is unjustly accused of murdering the siren. The law enforcement officers turn on him, combating the pureness of poetry as one. Injustice is a relative concept, that judges can apply.

Where did you get your recurring political and social commitment from?

It was the war that influenced me. I lived a relatively sheltered bourgeois existence as a child, and then suddenly we ended up living in abject poverty. Our house was destroyed by bombs. We literally had nothing anymore. The break with my previous life was very brutal. Every day, my family and I had no idea where we would sleep at night or when we would eat next. I think this experience inspired my social commitment. I also received assistance from left-wing progressive movements during my childhood.

Your second film, A False Note (1963), very clearly focuses on the theme of injustice.

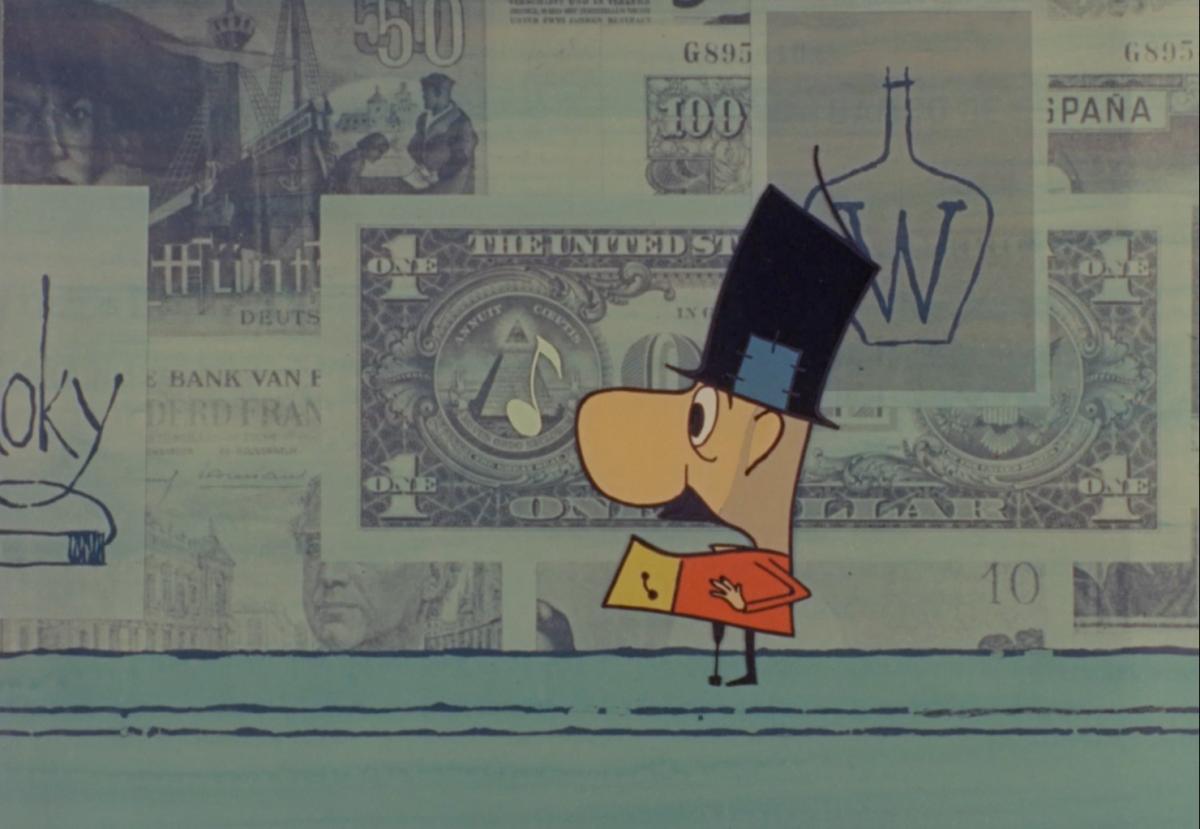

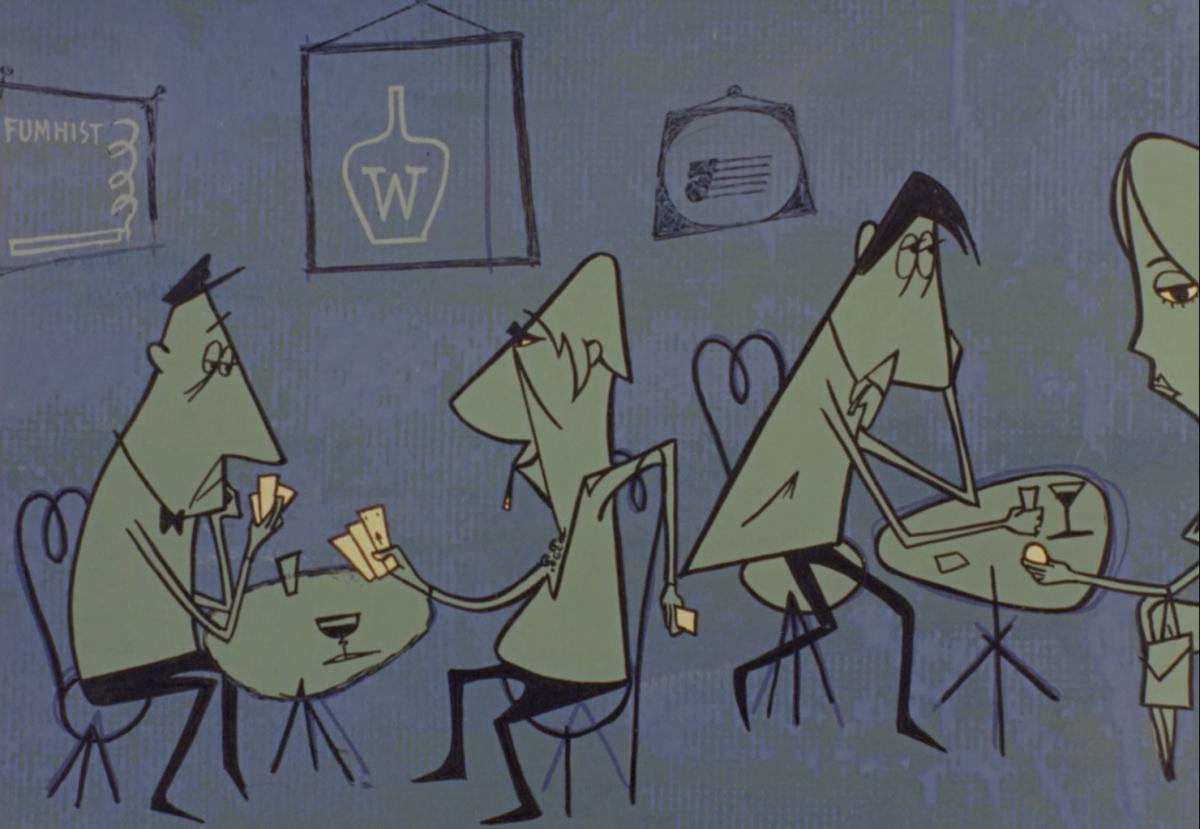

In A False Note, a small musician is confronted with poverty in an indifferent society. He sets out to beg for money but the melody he plays on his barrel organ always ends on a false note. It was my first film to be shown in cinemas. I used the prize money I received for Harbour Lights to buy a professional 35 mm camera from 1928. A False Note was made without support, without subsidies. I was able to recover some of my expenses because I made it in a film format that was suited for cinemas.

“Pamphlets: content over form”

How important is it for you to share your message?

Many of my films have a political or social message. I don’t know why I always return to these messages but they feel right. It is a form of expression. My films typically look very different when they have a more social message. None of my films is similar to each other because I always tended to focus on the content. If I estimated that my own graphic skills and own design skills were not up to the job or did not correspond with what I wanted to say, then I had no problems relying on the skills of another artist. Sometimes the style of the other designer was more suited to the message.

In To Speak or Not To Speak (1970) you convey your message in a very innovative manner.

To Speak or Not To Speak is one of my only films in which the characters speak. Here verbal language and design overlap. I also think it’s the first film ever to use text balloons. The media personality in this film asks vague, banal questions about the current political situation but the man he is interviewing is barely able to string a sentence together. If you do have a personality and an opinion, you run the risk of being used and repressed. The typography of the words in the text balloons reveals more about the personality of the different characters. In this film, I tried to express my political commitment in a humorous way.

You also use a lot of language and humour in the satire Goldframe (1969), which you produced one year earlier.

Yes, that’s true, even though not everyone appreciated Goldframe. The scenario tells the story of a fictional film producer, called Jason Goldframe, who always want to be the best at everything. His megalomania, his madness ultimately compels him to compete with his own shadow. The film was based on the film Goldfinger. It is a satire, that criticises the Hollywood style and method of filming. I submitted it to the Oscar Academy in Hollywood, as a provocation. They returned the film to me a few months later, without any comment. They didn’t find it funny. I later heard that they considered the story to be anti-Semitic. They thought that the main character was a reference to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Goldwyn was a Jew and they thought that I was mocking the Jews. They completely misunderstood my film.

You also chose to use a cartoon-like style for this film.

I was able to count on the collaboration of Willy Verschelde and Paul Van Gijsegem for the animation and the scenery. The main character and the background blend in nicely with each other in this film. Goldframe has no colour, it would have been redundant anyway. I was happy that this worked with the theme because I was unable to raise any financial support for this film. So I funded it myself and the black and white option was cheaper.

Every one of your films has a different style. How do you create it?

The content defines my style. I have to adapt the graphic style to my script. I also enjoy experimenting, discovering an uncharted path. I find it difficult to repeat myself. When I have made a film, it is a finished product. I don’t believe in retracing my steps. I find new ways, new risks and believe in experimenting. Perhaps every film is a reaction to the previous one. I get bored of using a technique for a long period of time, which is why I go in search of something completely new.

Is finding new techniques a time-consuming process?

Yes, the experiments were quite time-consuming but I did not make films for a living. I earned very little money with films, in fact I sometimes even lost money but I didn’t care. I had a family to provide for and I was fortunate that I had an income from teaching.

You founded the first animation school in Europe.

In the early Sixties, I taught applied art at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent. I had already made a film by then, called Harbour Lights. The director Geo Bontinck was impressed with what he saw and asked me to create an animated film department. I really loved the idea because I was already thinking about it. It was so foolish

that young people like me had to search for the information they needed. Founding the first animation school made me very happy as I was able to share my knowledge.

that young people like me had to search for the information they needed. Founding the first animation school made me very happy as I was able to share my knowledge.

“A conflict is usually individual in the case of aggression. When it is carried out collectively, this is called a war.”

When did you first receive funding for a film and how did you feel about this?

I was working on Chromophobia (1965). One day, Paul Louyet of the film division of the Ministry of National Education rang me up. They had heard about me and he invited me to screen Harbour Lights and The False Note in Brussels. And then he asked me whether I was interested in making a film for his film department. I never expected this and it made me very happy. At the same time, I was also worried because I feared that I would have to make an educational film. Possibly about a discipline that I was not familiar with, such as mathematics. But he gave me free rein to do what I wanted. I was the happiest man in the world and felt as if I had wings! I was given the opportunity to make the film I wanted, with financial support too. You cannot believe the enthusiasm I experienced while working on Chromophobia.

An army of grey soldiers strips the world of its colour in Chromophopia. In this film, you use simple geometric lines to underscore your message. How was this film received?

The Ministry submitted my film for the Venice Film Festival, to represent Belgium, where it won first prize for a short film. It was my first international breakthrough. I was beside myself. The ministry had other plans to fund Belgian animated film but unfortunately these fell through.

But this international success also generated a lot of new interest in you and new jobs.

I was contacted by an American company to make a series based on Chromophobia, but I didn’t think it would work. The second film would be much less persuasive and the third one even less so.

Your style was praised because you did not follow the typical American style. Why did you choose your own style?

I didn’t understand why people were so bent on mimicking the Hollywood style considering we have our own graphic tradition and own personality here. There were a lot of Belgian followers who created beautiful animation but who chose to follow this Disney style nonetheless. So why did we not use our own personality and our own graphic style to make an animated film?

Operation X-70 (1971) is another film about conflict but it looks quite different from Chromophobia.

I also enjoyed working on Operation X-70 very much. A former student of mine, Marc Ampe, assisted me. He created specific engravings with designs for the scenery and the characters.

The innocent population in this film inhales gases from bombs, which gives them wings. Why are there so many winged creatures in your films?

Perhaps because I dream of having wings myself. Or to overcome my own gravity.

War is a theme that has never been far from your mind, since your childhood. In 2015, you released Tank, about a World War I tank attack. How do you combine this theme with twenty-first century techniques?

I needed digital techniques for Tank. The tank’s movements were so complex that I couldn’t animated them. This is a drawn film with special effects. As I was not trained to use this technology and did not study it, I was forced to rely on younger people who knew the ins and outs of it. It is a lesson in humility, because I am incapable of doing this myself now.

“Oppression is what an individual or community experiences when a form of thinking, of action, of believing, is imposed.”

You already used digital techniques in the past, both for Taxandria (1994) and Atraksion (2001).

In Atraksion I combined live action with digital applications. We made the film in a studio of the Le Fresnoy school in Tourcoing, France. The characters seems to live in a graphic set thanks to the computer-controlled image pro- cessing. The characters walk through a desolate landscape, like prisoners in striped costumes. They are oppressed, seem stuck in their surroundings and accept their fate. A destiny is what some people undergo to because of their genetics, because they vegetate in a state of inferiority or because they feel their life is useless. The aimless path of one of the characters is disrupted when his curiosity is piqued by the one beam of light in the landscape. He objects to his fate and starts to walk towards it. Opposition is like a liberating revolt against oppression or occupation.

Aimé, the main character in Taxandria (1994), who resists the oppression of a dictatorship, is also curious.

In Taxandria, a boy named Aimé discovers the truth behind a stagnant, hidden dictatorship. The story of the feature film was slightly different from what I originally had in mind. I also had to hire a different script writer. The story of my novel L’Éternel Présent – Conte Philosophique (2017) is more closely related to what I had in mind.

Taxandria is often described as a less authentic Servais film.

I had written a script for a feature film, which I liked. But it was too long for a short film. I found some Belgian producers but the funding I raised proved insufficient. And that is how I ended up making a German, French and Hungarian co-production. I wanted to make an animated film starting from live action images, whereas the producers wanted to combine live action with special effects. So I ended up in the world of live action, where I had fewer contacts. It was a new experience for me, but these people did not understand animated film. They rejected it and I had to make many concessions. It never was the film I set out to make, it is not an animated film.

Can you tell me more about the scenery, which adds that sense of mystery you like so much?

I was fascinated with the artist Paul Delvaux’s magical-realistic ghost cities. He agreed that I could use his paintings in an animated film. But the producers were not interested in this and in a sense they were right. The iconography of railway stations and temples was insufficient for the narrative and did not offer sufficient oppor- tunities for different perspectives. That is why we decided to work with the artist François Schuiten. He was a huge support while I was making Taxandria. As a comic strip designer, he also understood the significance and process of animated film.

“You encounter mystery in old castles and houses and in the gaze of some women.”

Harpya (1979) marks a departure from your previous films, in terms of content and technique. You abandon the messages about commitment, choosing instead to create dark thriller in which a little man with a hat and moustache saves a harpy from death. The mythical creature, who is half woman, half predator, becomes a scourge for the man, dominating his life and pursuing him relentlessly, compelling him to lose his livelihood and his legs. Harpya won the Golden Palm in 1973 at the Cannes Film Festival. Which technique did you use for this film?

It was the first time that I dared to consider the type of cinematography that could combine animation and live action. I visited the Arthur Rank Studio in London to learn more about these techniques. They were amazing, but the price of this technology was prohibitive. So I had to find my own way. I spent months testing several techniques and experimenting with materials such as light-retaining microscopic balls on my animation desk. I ended up projecting the live action on a sheet of paper that retains the light, designing contours around the figures and cutting them out one by one. Fortunately I had an assistant. She cut out hundreds of images! Every figure was then placed on an image of the scenery, on which I projected the live action. It was an extremely complicated and time-consuming process. It took two years.

Were you satisfied with the result?

Every time I complete a film, I always feel as if I’ve made a bad film. I never achieve what I had in mind. It was the same for Harpya. “What a bad film this is”, or so I thought. You wouldn’t believe how disappointed I was. I showed the film to some friends and the silence after- wards was deafening. Not because they thought it was bad, as I initially thought, but because they felt that it was one of my best films. You cannot imagine how surprised I was when I learnt that the ministry had selected my film to represent Belgium in Cannes. There was such a huge contrast between the previous disappointment and the award of the Golden Palm.

Was this feeling inspired by perfectionism?

Yes, perhaps it was. I’m never 100% satisfied with my work.

After Harpya, you developed a cheaper technique, called Servaisgraphy. You were unable to test it on Taxandria, but you did use it for Nocturnal Butterflies (1998).

I really enjoyed filming Nocturnal Butterflies. It was a very interesting undertaking and I was able to use Servaisgraphy, which was completely different from the technique I used on Harpya. We filmed everything in black and white. These live action images were then printed on cellophane sheets, like with an animated film, by a device called the Servaisgraph. We then coloured the back of the sheets, placing them against the scenery. All the sheets were filmed image by image. It was a combination of live action and animation. Soon after, digital technology was invented and my system became outdated. My Servaisgraphy was redundant but it worked well on Nocturnal Butterflies, which makes me very happy.

The artisan character of Servaisgraphy is perfectly suited to the magical realism of Nocturnal Butterflies. Together with your first assistant, Rudy Turkovics, you were able to retain that dreamy, desolate atmosphere, where time seems to have stopped while mysterious women dance.

Nocturnal Butterflies is a tribute to Paul Delvaux. I greatly admired this painter and met him a few times. He was a very unassuming, nice man and a fantastic artist. I wanted to make this film as a tribute to him. Unfortunately he never saw it. I told him that I intended to use his work for a film but he died before it was released.

“Sagas and legends are the best way to feel asleep and were devised by bad sleepers.”

This is not the first time that you were inspired by the work of a Belgian artist. Which other artists shaped your ideas?

For Pegasus (1973) I was inspired by Flemish Expressionism. I have nothing but admiration for the Latem Schools. For Constant Permeke, Gust De Smet, Frits Van den Berghe to name but a few artists. I was really attracted to this style, I thought it was amazing. And I thought it was very well-suited to the script of Pegasus.

In Pegasus, a blacksmith is the last man standing in a society where fast-moving technological progress has taken over. The blacksmith glorifies the horse, out of passion for his profession but at the same time, he has created an obstacle to his own freedom in a maze of his own creation. Where did you get the idea for this story?

I lived near a poor farmer. He had just one friend, just one possession, but it was everything to him. It was his horse. Every evening he walked his horse, like we would walk a dog. He would pass by my house and I always took the time to chat with him. I thought he was fantastic because of the beautiful relationship with his horse. One day the horse fell ill so he brought it to the slaughterhouse in Ostend. Once home, he regretted his decision and immediately turned back. But he was too late, the horse had already been slaughtered. The farmer was so deeply saddened by the turn of events that he hung himself. This event made a huge impression on me. He had not committed suicide yet while I was working on the film. My film and the man’s mental revolution run parallel if you like.

How do you translate the texture of a painting and the atmosphere of a narrative into an animated film?

Pegasus was a lot of work, but fortunately I had some assistance. In animation, the cellophane sheets with the characters are laid over the scenery. I found the contrast between the flat colours of the former and the nuances of the latter very disturbing. I wanted to create more unity and I wanted the moving characters to have the same texture as the scenery. It took a lot of work to give the silhouettes a body colour with various layers of acrylics on top of it. If you look closely however, you will see that the characters are just as beautifully layered as the scenery. It’s as if they have stepped out of a painting. So all that work definitely paid off. We had to keep the animation simple, for budgetary reasons, otherwise we would have needed tens of thousands of drawings, which we couldn’t afford.

Het Lied van Halewyn (1976) and Winter Days (2003) are two animated shorts that were commissioned. Both of these films tell a story that is inspired by a legend or a saga.

They are both part of a series. Het Lied van Halewyn uses paper cut out animation to tell a story that was inspired by a medieval song. Halewyn’s hypnotic voice lures to the girls out of their villages into a dark forest from which they will never return. The Italian producers wanted to make a series about European legends, choosing two Belgians. One from Wallonia and myself from Flanders. This was a commission. Winter Days is a feature film, and the collective work of 35 animators. A Japanese filmmaker who also happens to be a friend of mine, Kihachiro Kawamoto, wanted to make a film that was based on a Japanese seventeenth-century poem. Much like every line of this poem was written by another poet, every filmmaker created a short one-minute fragment. We had no idea what the others were making. I chose a very traditional technique. It was a very short animated film about a man who opens his door to a cold heron but who becomes embroiled in his memories of a woman. I really enjoyed contributing to Winter Days.

“It’s my nature.”

During your career you continued to draw. At the same time, you also pioneered several new film techniques. You have also revisited themes that you love or which made an impression on you. Even now, at age 90, you continue to create stories and films.

Yes, I continue to work. It’s my nature. I have to be creative or I feel deeply unhappy. I cannot and don’t want to stop it. There are several projects in the pipeline. Not that I will be able to do them all because of my age of course. I’m currently working on my second novel and I hope to start filming a new film in a few months.

This text was originally published in Raoul Servais - Panoramic (Ghent: Borgerhoff & Lamberigts, 2018).

With the consent of www.raoulservaiscollection.com

Images (1) and (2) from Havenlichten (Raoul Servais, 1959)

Image (3) and (5) from Sirene (Raoul Servais, 1968)

Images (4) and (6) from De valse noot (Raoul Servais, 1963)