Winter Adé

After Winter Comes Spring – Presaging the Wende

“Eastern Europe placed great hope in glasnost and perestroika, those harbingers of change coming from the Soviet Union. But it was not foreseeable that these signals, the Polish Solidarność movement and, later, the East German Monday Demonstrations, would bring the end of the socialist system. But the processes of change had been underway under the surface for a long time.”1

At the beginning of the 1980s, it was still politically entirely unclear how long the fragile balance between the power blocs would last. Only in 1985, when Mikhail Gorbachev took office and introduced glasnost and perestroika, did people dare hope that it might be possible to overcome “the dangerous and primitive state of the bipolar world system,” as the Hungarian writer and sociologist György Konrád put it.2 would open the Hungarian border to Austria in June 1989 and the Berlin Wall would come down on November 9, 1989. These developments appear coherent in retrospect. But from a contemporary perspective they seemed in no way inevitable.

Among all the texts, images and musical works produced in the German Democratic Republic (GDR, or East Germany) and other Eastern European countries at that time, we are struck by the numerous works that can be read as courageous expressions of the coming changes. These works were almost seismographically able to express presages of change, which only much later became evident in the general consciousness. Film in particular emerged as a sensitive medium; nowhere more than in movies did the warning signs of the Wende gain such tangible power.

Many of these films, shot by both famous and lesser-known directors, exemplify a hope for increased political, economic and especially artistic openess. What these films have in common is an unusual perspective, exceptional artistic quality and the fact that they were made in the last decade of the Cold War. Some of these films – including feature and documentary, as well as experimental and animation films – were produced in the official studios of Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, Rumania, Czechoslovakia, East Germany and the Soviet Union. Others were produced on the periphery of mainstream cinema, by lone filmmakers or in the in underground art scenes.

East Bloc Cultural Policy

The conditions of cultural policy in different East Bloc countries were as different as the styles of individual filmmakers. To understand from today’s perspective why these films were considered forward-looking at the time requires a brief overview of the different backgrounds of these countries under the dominance of the Kremlin. In East Germany between 1949 and 1989, relatively liberal periods alternated with periods of increasing restrictions, with the latter clearly dominant. It is revealing that whenever signs of a political “thaw” emanated from the Soviet Union, the East Berlin party leaders – otherwise so strict in their adherence to Moscow – would oppose the liberalizing tendencies. When Leonid Brezhnev succeeded Nikita Khrushchev as leader of the Soviet Communist Party in 1964, for example, the Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) turned back to the “default” domestic policy of censorship and mistrust in its notorious 11th Plenum in December 1965. The result was that almost an entire year’s worth of films made at the DEFA Studio for Feature Films was effectively sacrified for a quasi-restoration of Stalinism – a blow, or Kahlschlag, from which East German cinema would never recover.

Over twenty years later history repeated itself, but this time as a farce. After 1986, when under Gorbachev paternalism and indoctrination were reduced in the Soviet Union, banned Soviet films were screened for the first time, including in East Germany. There also appeared new, unexpectedly audacious Soviet films that caused a sensation, such as: Igla [Needle] (Rashid Nugmanov, 1988), a film about the drug mafia that was the key title of the Kazakh New Wave and one of the most successful perestroika films ever; and Chuchelo [Scarecrow] (Rolan Bykov, 1983/86), about a 12-year-old girl who is bullied by her classmates. Chuchelo was one of the first films to announce Gorbachev’s new policies; it premiered in the USA in June and in East Germany in September, 1987.

East Germany soon sealed itself off from these new ideas and changes, however. While watching Soviet films had previously been considered an unwelcome obligation for East Germans, who were required to see them, now the public was deprived of seeing several of the most important perestroika films. East German officials were afraid of the “fresh Soviet wind” and banned parts of the Soviet film program that was scheduled for the 31st Leipzig International Documentary and Animation Film Festival. In mid-November 1988, the theatrical distribution of Soviet films that had been shown during the GDR’s annual Soviet Film Festival was cancelled. Films affected by this decision included: Monanieba [Repentance] (Tengiz Abuladse, 1984), a coming-to-terms with Stalinism that its director called the “first swallow of Perestroika;” Komissar [The Commissar] (1967, banned until 1988), Aleksandr Askoldov’s film about a female comissar and a Jewish family during the Russian Civil War; Kholodnoe leto pyatdesyat tretego [The Cold Summer of 1953] (Aleksandr Proshkin, 1987), the story of two political prisoners discharged from prison after Stalin’s death, who defend a village against criminals; Zavtra byla voyna [Tomorrow Was War] (Yuri Kara, 1988), about a girl who discovers the truth about Stalin’s repressions; and Gleb Panfiov’s Tema [The Topic] (1979), which tells the story of an artist who realizes he has sacrificed his creativity for privileges.

The contradictions between East Germany and the Soviet Uunion continued to escalate. Except for a few titles. Under the aegis of General Manager Hans-Dieter Mäde, feature film production at East Germany’s DEFA Studios, had sunk into its death throes. The studio delivered humorless comedies, out-of-touch images of the working world and decorative historical films. There were hardly any aesthetically daring confrontations with the explosive issues of the time. In DEFA documentary films, in contrast, reflections of reality were more noticeably confrontational. The works of East German directors such as Jürgen Böttcher, Volker Koepp, Konrad Weiß and others saved the honor of East German cinema in this period. Helke Misselwitz’s groundbreaking documentary Winter Adé (1988) about the lives East German women, which put the embellished image of women into perspective, was also exceptional in East German filmmaking of the late 1980s.

Asynchronous cultural policies, sometimes on a vast scale, also marked film production in the other socialist countries. The cinemas of Hungary and Poland, for example, more or less represented openness for East Bloc avant-gardes. Even under martial law, which was in effect in Poland from December 1981 to February 1989, filmmakers were able to produce works of stunning political openness, such as: Krzystof Kieślowski’s ten-part televised miniseries, Dekalog [The Decalogue] (1989); Piotr Szulkin’s internationally acclaimed sci-fi film, Wojna swiatów – naste ̨pne stulcie [The War of the Worlds – The Next Century] (1981/83); or the story of a failed opportunist, Tańczący jastrząb (The Dancing Hawk] (1977), by Grzegorz Królikiewicz. In neighboring East Germany, such films would have been rejected as scripts, if they had been submitted at all. As of summer 1987, the granting of extensive autonomy to studios and production groups in Poland in effect dismantled censorship. In Hungary, cautious de-Stalinization under party leader János Kádár in 1959 had established a context in which the Béla Balázs Studio had evolved into an institution where a range of formal and stylistic experimentation was possible. When, in the 1980s, Hungary increasingly moved away from Moscow both economically and politically, everything became artistically possible; this was especially true in film, where only a few taboos remained, such as blasphemy, pornography and provoking the USSR. Excellent and representative examples from this period of Hungarian filmmaking include A Kis Valentinó [The Little Valentino] (Andras Jeles, 1979), a surreal-documentaristic genre picture set in Budapest, and Gábor Bódy’s postmodern vivisection of Hungarian society, Kutya Eji Dala [The Dog’s Night Song] (1983).

Diametrically opposed conditions prevailed in Romania and Bulgaria, where only rudimentary freedoms existed and paranoid secret service agencies opposed any deviation from the party line. Titles that represent production in this period include the Romanian film Ioane, Cum Constructii? [Ion, What’s Going on at the Contruction Site?] (Sabina Pop, 1983) and the Bulgarian film Az, grafinyata [Me, the Countess] (Petar Popzlatev, 1989). In Czechoslovakia, as is known, the suppression of the “Prague Spring” in August 1968 blighted some of the most hopeful political, aesthetic and filmic developments in the East Bloc; after this blow, Czechoslovak film language veered towards the trivial, to an extent only paralleled by East German film production. Věra Chytilová’s avant-garde films – Sedmikrásky [Daisies] (1966) and Panelstory aneb Jak se rodí sídliste [Wall Stories] (1979/1981) – presented an exception to this, but the distribution of her films was supressed or blocked by officials. Finally, a unique status applied to Yugoslavia, whose multi-ethnicity caused it to be seen as part of the East from the western point of view, and as the West by Moscow and other east bloc countries.

Winter Adé – the Film and the Series

To date little research has been done on the articulatory function of cinema and filmmaking between these antipodes, or on their function as a membrane and catalyst of social developments. The film series Winter adé – Vorboten der Wende [Farewell to Winter: Presaging the Wende], which premiered at the 2009 International Berlin Film Festival, called attention to this phenomenon. It offered a first glimpse of the specific distinctions between different totalitarian systems, as well as a series of exceptional, visionary films that were wrested from these systems. Helke Misselwitz’s 1988 documentary Winter Adé was part of the series and of the chapter of film history associated with the peaceful revolution in East Germany in fall 1989. It belongs to the group of East German and East European films that were produced in the last decade of the Cold War – and already articulated a premonition of upcoming profound changes.

Winter Adé decribes a train ride from one end of East Germany to the shortly year before the country’s collapse. On her journey from the industrial, mining town of Zwickau, in Saxony – near where Misselwitz was born – to the island of Rügen in the Baltic Sea, the director meets and talks to women of different ages and social backgrounds. The women’s candid statements and observations create a kaleidoscopic panoply of memories, longings and disappointments, which vividly portrays the atmosphere and life in East Germany at that time.

Taking the train was the usual way to travel in East Germany. Few people had automobiles. That Winter Adé became a “rail movie” reflected normal living conditions, and was not the not the result of a search for a strong metaphor. Nevertheless, a metaphoric layer is there. Traveling by train was often an exhausting undertaking and was experienced as a symbol of the many makeshift arrangements that one encountered on a daily basis. You had to be somewhat hardened to ride with the Deutsche Reichsbahn:3 unfriendly staff, abitrary schedules, ramshackle or dirty cars. The route from south to north followed in the film was the same route that thousands of GDR citizens followed to go on vacation year after year, in the absence of other available destinations. This meant that it would be recognized by the viewers.

The film and journey end at the Baltic Sea, but in a particular way. The camera travels with the train onto the train ferry in Sassnitz, then the ship casts off. The tracks, whose rail joints have provided a leitmotif throughout the film, suddenly grasp the void, and the country called the GDR stays behind. A contradictory final scene: While the camera pans over the icy deck, we hear – of all things – Janis Joplin’s ‘Summertime’4 off camera. In that moment, nothing could be more foreign than the thought of summer. But Misselwitz almost defiantly returns to the optimism of her film title, modifies it through the warm voice of the singer and leaves the viewer with suprisingly clear confidence. How right she was, was proven a year later.

When Helke Misselwitz screened her film at the Leipzig International Documentary Film Festival in 1988, it was like a dam bursting. Never before had East Germans been so open and matter of fact as they talked, in front of the camera, about the intellectual and practical circumstances of their lives. The film with the programmatic title marked the untenability of offical public opinion. It indicated a noticeable change of mood in the eastern part of Germany, which in fall 1989 – again in Leipzig – cut a new course. In no way was the film met with unanimous enthusiasm. Especially the representatives of East German television, who had a great deal of influence at the festival, tried to block the success of the film. The history of the film’s production and its reception once again attests to the many contradictions that existed in East German society, which can by no means be seen as a homogenous system.

Over and above the almost sensational signal it sent at the time, Winter Adé continues to be an artistically important and aesthetically coherent film, in which the interaction between directing, cinematography and editing yields a composition that one could almost call choreographic. But above all it is the accuracy and tenderness of its observations that make the film stand out in late DEFA film history. As a result of Misselwitz’s personal style, her gentle interviews and her empathy for the women she meets, her film achieves those qualities that still impress us today. Before the premiere of Winter Adé, there was no tradition of a feminist approach to film directing in the GDR. Of course, there were forerunners Misselwitz could connect to in literature5 and, at points, in film. One could cite the documentary Hinter den Fenstern [Behind the Windows] (1983), by Petra Tschörtner,6 based on interviews with three couples, or the banned and destroyed interview film, Frauen in Berlin [Women in Berlin] (1981), by the Indian film student Chetna Vora.7 Not coincidentally, both directors were students alongside Helke Misselwitz at the Hochschule für Film und Fernsehen in Potsdam-Babelsberg. At the same time, Winter Adé cannot be reduced to the single characteristic of its female perspective. The film neither insists on, nor draws its explosiveness from this. Misselwitz’s film is an exception from the rule, yet incorporates a considerable reevaluation of traditional structures, which – no longer able to be flexible or change – collapsed shortly after. The film conveys an atmosphere of departure, whose potential proved to be limited: the changes advocated by the film were obsolete – and in its obsolescense irreversible – by fall 1989, at the latest.

The film Winter Adé is thus a double farewell. Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallerleben’s famous song ‘Winter adé [Farewell Winter]’, which gave the film its title – although you don’t hear the song in the film – contains the line “scheiden tut weh” [parting is sorrow]. Today the selection of the song’s title for the film’s title appears crystal clear, refering as it clearly does to the metaphor of a “thaw,” which had already before been associated with the hope for “socialism with human face.” The poet’s biography also awakens certain associations with the politial situation in the late GDR. Von Fallersleben (1798-1974) was one of the spokesmen of the 1848 revolution; he was banned from his profession in Prussia in 1842, after which he lived in different places in exile.8 That a “successful revolution” would finally take place in Germany in 1989 was not possible to predict in 1988 – the paralysis was too omnipresent. And yet, this change is already presaged in Winter Adé, where those tectonic shifts that would lead to the upheaval are almost seismographically inscribed.9 While the first mass demonstrations took place in Leipzig that mobilized hundreds of thousands of people, and while almost one million people went out into the streets for democracy in East Berlin on November 4, 1989, Helke Misselwitz was in the USA at the inviation of the University of Massachusetts.10 She returned to East Berlin immediately after the Wall came down, marking the end of the Cold War, on November 9, 1989. There she found a different country.

- 1Program of the film series Winter adé – Filmische Vorboten der Wende. Berlin: Deutsche Kinemathek Museum für Film und Fernsehen, 2009. The term “Wende” denotes the period surrounding the fall of the Berlin Wall and unification of Germany in 1989-1991.

- 2See: http://www.konradgyorgy.hu/karlspreis.php?id=174[/fn] There was still a long way to go before Gyula Horn

Hungary’s foreign minister and one of the leaders of radical reform who transformed the Hungarian Socialist Worker’s Party (MSZMP) into the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP) in 1989. - 3The last line of the final credits in Winter Adé refer to this publicly owned railway company: „Thanks to Deutsche Reichsbahn and the Central-European Sleeping and Dining Car Corporation for their own unconventional assistance.“

- 4From the Cheap Thrills album Joplin made with Big Brother and the Holding Company (1968).

- 5For instance books by Brigitte Reimann (1933-1973) or Christa Wolf (1929-2011), and especially Maxie Wander’s (1933-1977) interviews with women published under the title Guten Morgen, du Schöne (1977).

- 6Petra Tschörtner’s (1958–2012) student film was awarded the main prize at the Oberhausen Film Festival in 1983.

- 7Chetna Vora, born in India, studied at the HFF in Potsdam-Babelsberg, where she met cameraman Lars Barthel. They worked together, married and had a child. Her student film Frauen in Berlin was withdrawn and destroyed by the officials of the HFF; only a poor quality video copy still exists. Vora died while shooting a film in India. Years later, Barthel made a film about her, entitled Your Death Is Not My Death (2006).

- 8Von Fallersleben wrote some of the most famous German children’s songs, including ‘Alle Vögel sind schon da [All the Birds Are Already Back]’, ‘Ein Männlein steht im Walde [A Little Man Is Standing in the Forest]’ and ‘Der Kuckuck und der Esel [The Cuckoo and the Donkey]’. He is also the author of ‘Lied der Deutschen [Song of the Germans]’, whose third stanza is used as the German national anthem.

- 9Different dynamics underlie the fact that it was impossible to reform the GDR from these beginnings, and that is a different story.

- 10Helke Misselwitz, Thomas Plenert (camera) and Gudrun Plenert (editor) were on tour in the USA from October 15 until November 15, 1989. Barton Byg, professor of German Studies at UMass Amherst, had spontaneously invited them after the Leipzig Film Festival. Zeitgeist, a New York film distributor, acquired the distribution rights for Winter Adé. The film was released on VHS, 16mm and 35mm in the US on June 15, 1990 and is known in the US under various titles, including: Winter Adé, Adieu Winter and Goodbye to Winter.

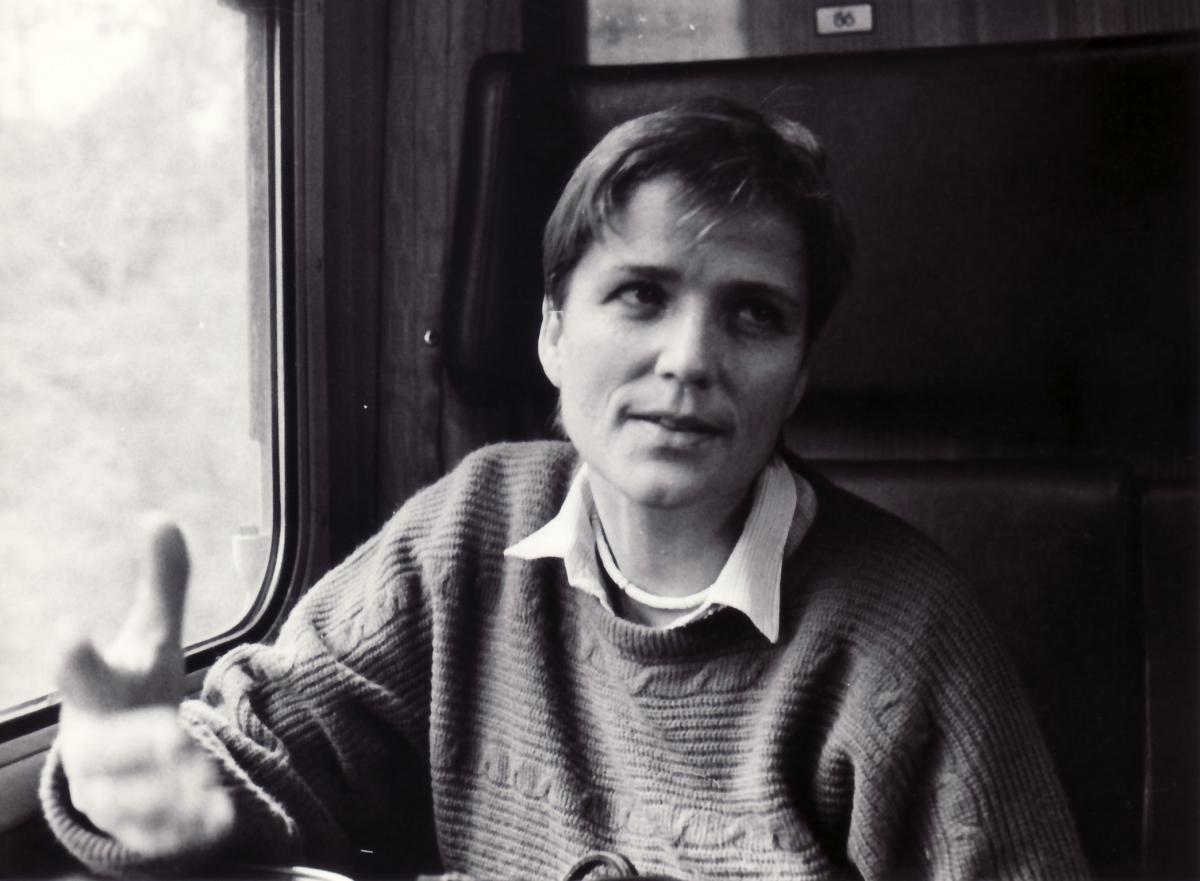

Images from Winter Adé (Helke Misselwitz, 1988)

This essay is based on Claus Löser’s introduction to the catalog accompanying the 2009 Berlinale retrospective entitled Winter Adé – Filmische Vorboten der Wende and was expanded for the DVD release by the DEFA Film Library.

Courtesy of the DEFA Film Foundation and Claus Löser.

Milestones: Winter Adé takes place on Tuesday 24 October 2023 at 19:30 in Cinema RITCS, Brussels. You can find more information on the event here.