Week 44/2024

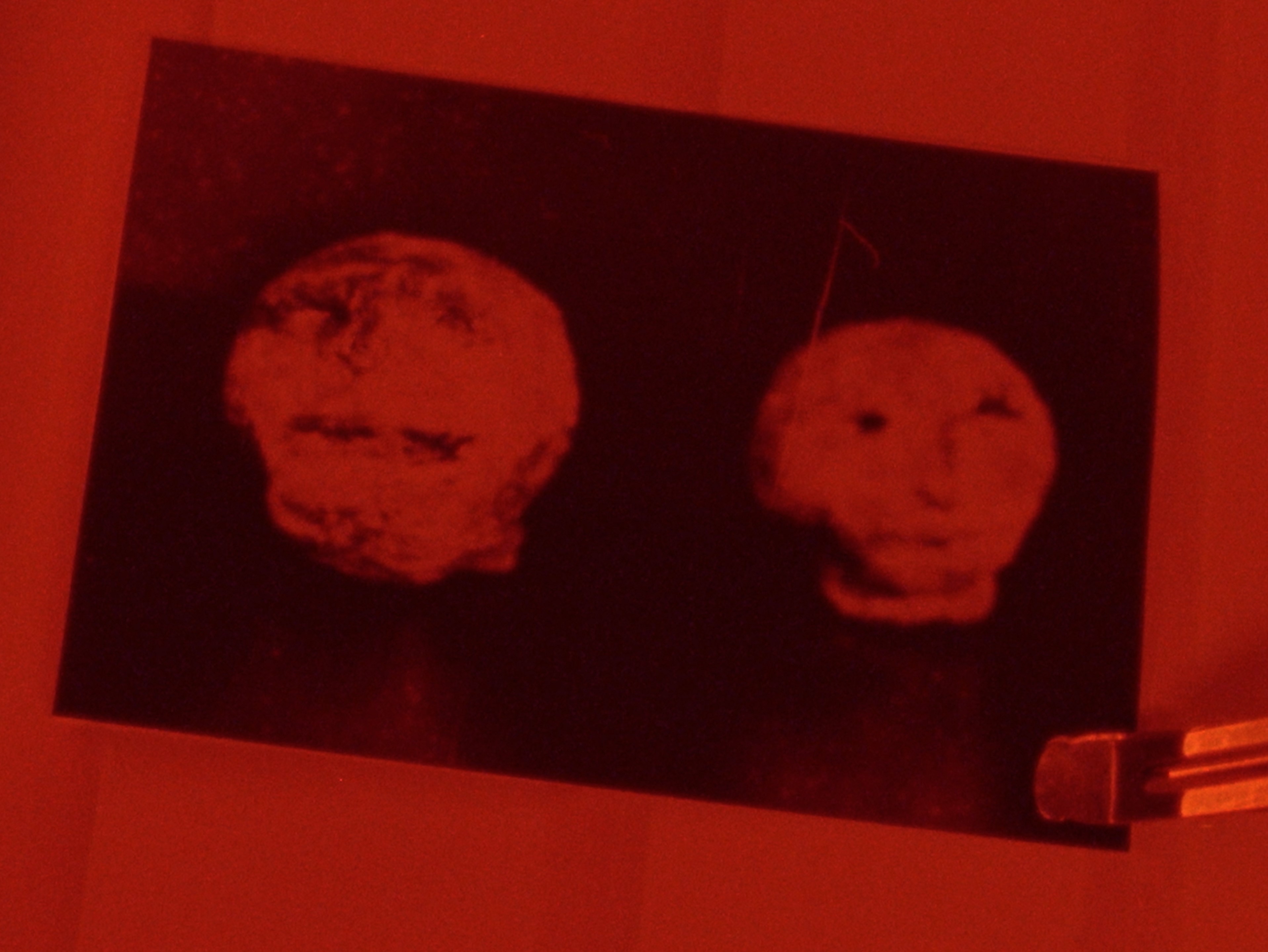

On Halloween, Belgian filmmakers Chloë Delanghe and Mattijs Driesen will present Hexham Heads, their co-directed film, at Art Cinema OFFoff. Their film is based on a ghost story deriving from the English town of Hexham, where a family was terrorized by a series of paranormal occurrences after bringing home some small stone heads. It is a re-account of this story and a re-imagination of the horror film genre, in which spaces, objects and the photographic process engender suspense. On this festive horror-evening, creators of the soundtrack Sam Comerford and Branwen Kavanagh will give a concert. After that, Delanghe and Driesen have chosen a surprise Halloween film to share with you.

In anticipation of this event, I asked these seasoned horror fans which other films they’d recommend. Their first choice is The Shining by Stanley Kubrick, stating: “The trope of the gloomy haunted house evoking a domestic trauma-psychology is transformed and expanded here into a gigantic, brightly lit hotel evoking a historic injury. This haunted space is defined by its labyrinthian corridors, in which time and place are confused, and wherein the violence of both psychology and history is continually repeated.”

Their second film of choice is Smile 2 by Parker Finn, who has declared The Shining his favourite film of all time and has cast Ray Nicholson, son of Jack Nicholson, in his latest instalment of the Smile franchise. “We haven’t seen this one yet, but we’re looking forward to it,” say Delanghe and Driesen. “The first one was far from great, but it had a truly weird ending. And even bad horror films always have interesting stakes.”