Nina de Vroome

Nina de Vroome (1989) is Dutch filmmaker, teacher and author. She studied film at KASK / School of Arts Ghent and graduated with Waves (2013). Her filmography includes Een idee van de zee [A Sea Change] (2016) and Het geluk van honden [A Dog’s Luck] (2018). Her films were shown at international festivals such as Visions du Réel and International Film Festival Rotterdam. She is a writer and editor for Sabzian. As a teacher she is involved in various educational projects. She makes collages and engages in collaborations as a sound engineer and editor. More information about her work is available on her website.

Nina de VroomeNina de VroomeWeek 5/2026

The first film of this week is called Met Dieric Bouts. André Delvaux wrote the film together with author Ivo Michiels. It is not about Dieric Bouts, but with him. Delvaux and Michiels enter the pictorial universe of the early Flemish Master, while simultaneously filming the very process of writing, shooting and composing the soundtrack. The work of Bouts becomes both guide and companion. After the screening, Wouter Hessels will speak with Sigrid Bousset, biographer of Michiels. Reflecting on the act of writing a biography about her literary idol, she once said: “Ivo had fallen from his mythical construct, and thereby I had fallen from mine.”

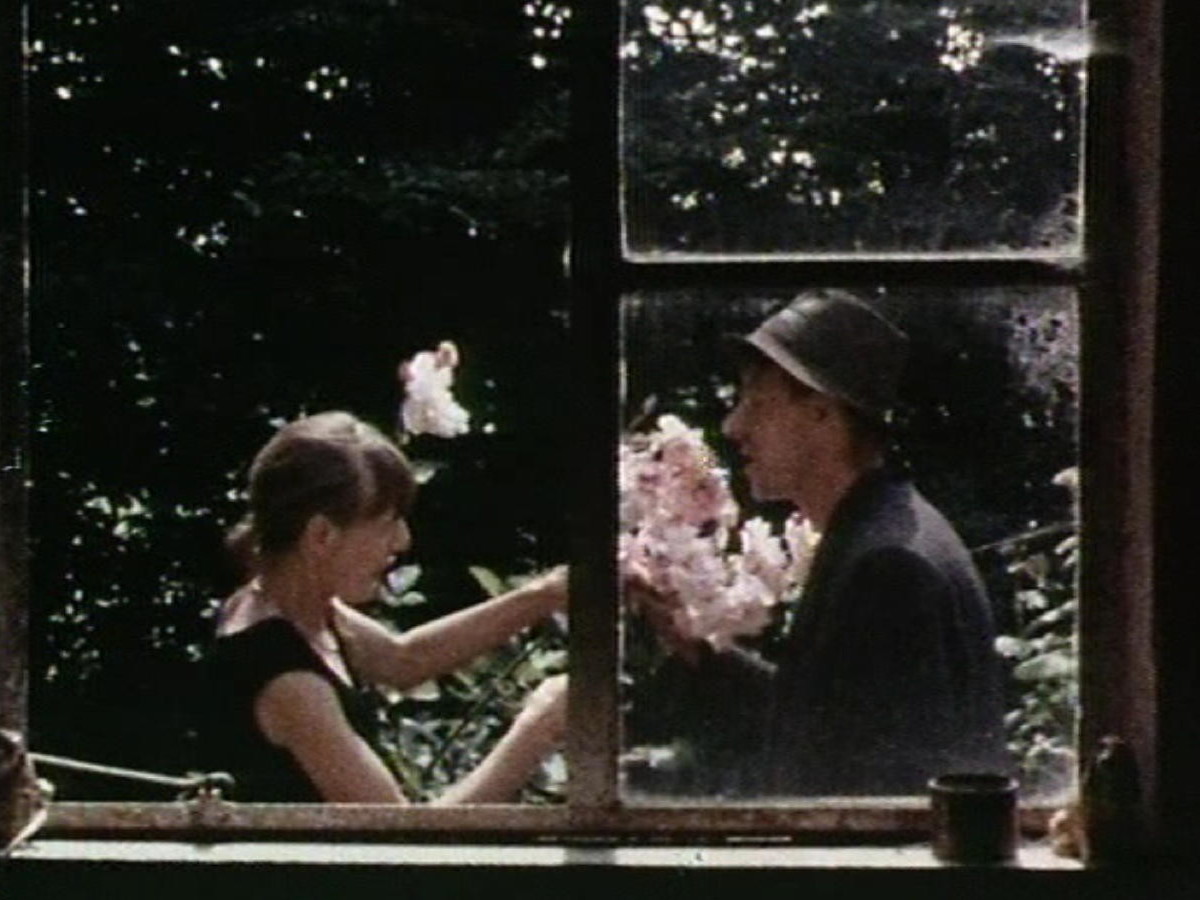

In Douglas Sirk’s melodrama All That Heaven Allows, a widow falls deeply in love with her gardener. Consequently, she receives a television set from her children , who aim to silence her desire. When the TV salesman installs the set beside her Christmas tree, she collapses onto the couch and watches her own fractured reflection in the dark screen, as he boasts: “All you have to do is turn that dial and you have all the company you want, right there on the screen. Drama, comedy, life’s parade at your fingertips.” She is offered all that heaven allows, on the condition that she remains a quiet spectator.

In Letter from an Unknown Woman by Max Ophüls, a young woman knows exactly who she loves and why their fates are intertwined. The man of her desires, a celebrated concert pianist, barely remembers her. She is his admirer, his audience. In a letter she writes to him, her tragic position is revealed: she is condemned to remain both spectator and specter. “By the time you read this letter, I may be dead. If this reaches you, you will know how I became yours when you didn’t even know who I was or that I even existed.”

Week 50/2025

This week you are invited to the library of LUCA School of Arts, Sint-Lukas Brussels campus, where a scintillating collection of publications in the field of (audio)visual arts will be the backdrop of a film program of 16 millimetre experimental films by Len Lye, Babette Mangolte, Peggy Ahwesh, Jeff Keen and Paul Sharits. After the screening, the evening will continue with music and kinetic Scopitone films curated by Photokino.

The two other selected films of this week are reminiscences of Palestinian lives that are marked by expropriation and expulsion. The title of Lina Soualem’s film Bye Bye Tiberias (2023) refers to the village where her great-grandmother once lived, before being chased from her home in 1947. Lina’s mother is the actress Hiam Abbass, who took Lina swimming in Lake Tiberias when she was a small child, “as if to bathe me in her story,” she recalls. The film is a personal portrait of four generations of women, shaped by exile and memory.

Ma’loul Celebrates Its Destruction by Michel Khleifi takes place in the village Ma’loul, which was destroyed in 1948, also by the Israeli forces. Once a year, the former inhabitants are allowed to visit their village. During this day, older generations recount memories while children play among the rubble. As Nurith Gertz and George Khleifi wrote, “Alongside the static preservation of an enchanted past image, [the film] also excavates the layers of memory. Thus it transforms the static narrative of the past resurrected in the present into a story of the remembrance of the past, its recognition and processing, as a working through, as a stage toward a return to life in the present and its continued progression to the future.”

Week 44/2025

This week is Halloween inspired. The films I’ve chosen are all about transformations, evoked using animatronics, puppets, masks, prostheses and lots of slime.

When Roald Dahl released his book The Witches in 1983, puppeteer master Jim Henson bought the rights and hired a rather unusual choice of director to shoot the film. Nicolas Roeg, known for his experimental, sensual and disturbing films, accepted the task of making a film for children. In The Witches, a little boy eavesdrops during a gathering of the so-called “Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children”, which turns out to be a confederacy of witches who plot to turn all children into mice.

In The Thing by John Carpenter, researchers on Antarctica discover an alien entity that can take the shape of every living being, consuming the flesh from the inside, filling the skin of its victim as if being taxidermized. Lacan wrote of the “horrendous discovery” made in the film, “that of the flesh one never sees [...], the flesh from which everything exudes, at the very heart of the mystery, the flesh in as much as it is suffering, is formless, in as much as form in itself is something which provokes anxiety. Spectre of anxiety, identification of anxiety, the final revelation of you are this – You are this, which is so far from you, this which is the ultimate formlessness.”

The third film of the selection is Jaws by Steven Spielberg. Antonia Quirke wrote of the film that passing by the shark’s jaws is a topological description of the afterlife, “a portal at which you stare and stare to discern the other side of life.” And Serge Daney questioned: “Who is the shark? Nothing more than the actualisation – from a hallucination – that there is something rotten inside which attracts the fish.”

When not in the cinema this week, I invite you to dive into Sabzian’s Film Index to discover our selected quotes on film.

Week 39/2025

In Theorema, a young man walks into a bourgeois household to disturb its order fundamentally – and tragically. This film is an enigma. For me, it is one of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s most fascinating and haunting films. In mathematics, a theorem is a proposition that ‘is not self-evident but proved by a chain of reasoning, a truth established by means of accepted truths.’ With its title, the film promises structured reasoning. But it also promises a deity – the a divine figure who emerges from the rubble of the community the handsome stranger will leave behind.

In the film Inclusief, Ellen Vermeulen observes children who try to find their place in the classroom. Children with different educational needs not only reveal the challenges of inclusive education but also bring to light fundamental questions about the role and purpose of education at large. Besides her classroom observations, Vermeulen also shows the solitude that exists in every child who is not at the same stage as the rest. The screening is a double bill with Vallen en staan, a film by Lauranne Van den Heede about three young children in an experiential primary school in Antwerp.

Watching the films by Frans van de Staak, as a fellow Dutch person, I can say that there’s something unmistakably Dutch about the way people talk, the rooms they inhabit, the words they utter. These words are square, direct and tricksy too. The titles of his films suggest a puckish director, a poet who is out to deconstruct language, to hold the absurdity of each word against the light. In his retrospective at CINEMATEK, you can find titles like: Terzake [To the Point], De onvoltooide tulp [The Imperfect Tulip], Het vertraagde vertrek [The Delayed Departure], Op uw akkertje [Your Garden Plot], Ongedaan gedaan [Deed Undone], Lastpak [Nuisance], Rooksporen [Traces of Smoke] en Windschaduw [Windshade]. This week I picked Optocht [Procession] and De korzelige klant [The Crusty Client] for you.

Week 24/2025

This week offers some opportunities to meet curators and filmmakers.

At De Cinema in Antwerp this Wednesday, Maryam K. Hedayat, director of Studio Sarab, will introduce two films she co-curated together with Roya Keshavarz: A Move (Elahe Esmaili, 2024) and My Stolen Planet (Farahnaz Sharifi, 2024). Both poetically and politically, the films explore the themes of memory, resistance and identity in contemporary Iran. The tension between women’s private and public lives in Iran lies at the heart of these films.

New Women, a silent film from 1935 by Chusheng Cai, shows the struggle of an intellectual who’s striving for independence. She sees herself confronted with the unsurpassable restrictions on women who aspire to a life in the public eye. This screening will be accompanied by live piano music at CINEMATEK on Thursday.

De Humani Corporis Fabrica by Véréna Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Tailor will screen at Bozar on Wednesday. In this film, the exterior world where social and feminist struggles take place no longer exists; instead, the body is presented as a psychedelic landscape shaped by the gaze of others. Following the screening, there will be a Q&A with Paravel moderated by filmmaker and curator Eva van Tongeren.

Week 18/2025

This week’s selection is about loss and mourning. These three films deal with the transformative relation with those on the brink of death, the memory of those who are no longer there, and the rites around the dead body.

A series of films on death is running in Brussels at Nova Cinema, amongst which are three screenings of Des morts (1979) by Jean-Pol Ferbus, Dominique Garny and Thierry Zéno. The trio travelled almost two years around the world to document death rituals. Both poetic and brutal, the film is between an ethnological study of the morbid and cinema with a punch.

The contrast with The Mourning Forest (2007) by Naomi Kawase could not be greater. A soft, contemplative film on a nurse in an elderly home who is grieving for her dead child. A male resident of the nursing home who has dementia takes her to a forest, where there seems to be something to be found that is connected to his late wife.

The third film this week is by Pim de la Parra, a Dutch-Surinamese filmmaker who founded the film magazine Skoop during his studies at the Netherlands Film Academy. He produced the first Surinamese fiction production called Wan Pipel (1976), which was an attempt at post-colonial nation building and a promotion of religious diversity. A Surinamese-Dutch student returns to Paramaribo to spend time with his dying mother. While he is there, he falls in love with his home country and with a Hindustan girl.

Week 9/2025

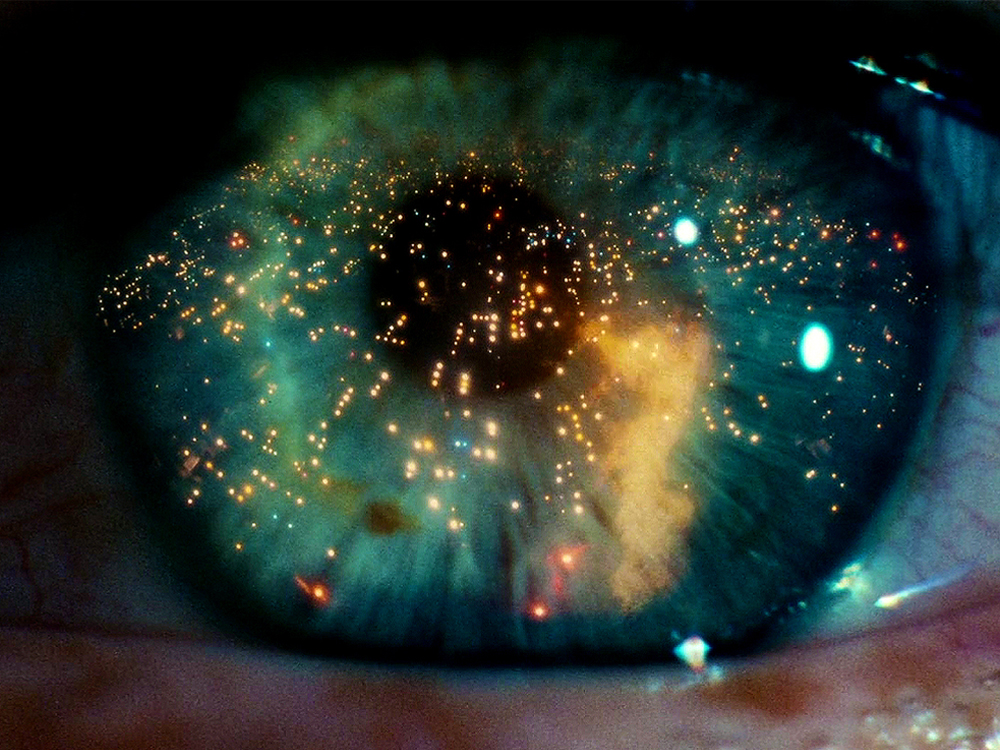

Yesterday, when walking in the street, I imagined a studio lamp crashing next to my feet out of the blue, like a star falling from the sky. When I would take a closer look at it, I would see its brand, Sirius. This happened to Truman Burbank, who begins to suspect his life is some sort of TV show. The Truman Show by Peter Weir has been analysed intensively, using theories by the likes of Marshall McLuhan, Jean Baudrillard, or Slavoj Žižek, who tried to dissect my first pick of the week as well. Screened as part of a commemoration in David Lynch’s honour, Eraserhead follows the fate of Henry, who becomes a father and is deemed to care for a helpless and repugnant baby. On the subject of the gentle and frightened victim-hero of Lynch’s debut film, Žižek questions: “What, then, if THIS is the ultimate message of Lynch's film - that ethics is ‘the most dark and daring of all conspiracies,’ that the ethical subject is the one who effectively threatens the existing order?”

My last film tip is Guérilla des FARC, l’avenir a une histoire by Pierre Carles. He went to visit the FARC guerrillas in Colombia and see for himself the people who had systematically been described as “narco-terrorists”. There, he observes Nathalie Mistral, a guerilla from France, reading an article that has appeared about her. As she quotes the article, she laughs: “Madame Mistral chose for the jungle and left behind her children. She doesn’t even remember how many.” Carles proposes a “counter-discourse”, even if it can be called propagandistic. “If propaganda is about spreading minority ideas and dominated viewpoints, there is no need to have any qualms about it.”

Week 6/2025

“I love dollars!” It sounds like the anthem for our times. Today it screeches in stark blue and red, but it has lost its promising ring. The neoliberal ghoul is a balding bank employee, just like the one Johan van der Keuken interviews in his film I Love Dollars (1986). He leans back explaining his theory: “At every moment in time there is the same blood circulating in your body. When you have a cut, some of that blood streams out and your body is generally injured. I am not a physiologist, but if you’d pump more blood into the body, you’d have a very awkward result indeed. Now when we pump too much money into an economy, we get a very awkward result and that is inflation, which impairs the workings of the economic body and leads to wounds.” Van der Keuken confirms: “You can see the body as being inflated.”

In 1980, the year following the Iranian Revolution that overthrew the Shah and led to the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Jocelyne Saab visited the country to understand what the people were living through. Her film has the telling title Iran, Utopia in the Making.

Two years ago, videos of Iranians chanting “Woman, life, freedom” went around the world. With his film The Seed of the Sacred Fig, Mohammad Rasoulof returns to this momentum as if to rekindle the flame that the state apparatus has tried to extinguish ever since. This household drama reveals how a family becomes haunted by the state, represented by a gun tucked in father’s belt. In Spectres of Revolt, Richard Gilman-Opalsky states that a social system should be haunted by the miseries it proliferates, and “it should be haunted by the threat of mutinies on the horizon.” Or much closer to home, in the bedroom of your own daughters…

PART OF Sabzian Events

Johan van der Keuken Retrospective

Week 50/2024

This week’s selection involves art in film – and a dog.

After the last-minute cancellation of the screening of El sol del membrillo (1992) last march, our patience will be rewarded with a new chance to see this mesmerizing visual meditation on the beauty of the natural world by Víctor Erice. Film historian Steven Jacobs will introduce this documentary on the work of the painter Antonio Lopez. The film captures the artist’s attempt to paint the quince tree in his garden while the seasons change and the sunlight reveals infinite nuances of colour and shadow.

In Brussels these coming months, you will have the chance to see the oeuvre of Ulrike Ottinger during the retrospective in the CINEMATEK. Ottinger began her career as a painter, lithographer and photographer, and her films are distinctly the work of an artist. She made a number of ethnographic documentaries that have continued to inspire her fiction, infusing her compositions with eccentric rituals and florid costumes. This week, Cinema Ritcs presents Freak Orlando (1981). Inspired by Virginia Woolf’s novel, it is a camp tale of the main character of Orlando who traverses time to meet the freaks of each century.

In De Studio in Antwerp, film scholar and teacher at Ritcs Wouter Hessels will give a lecture on Italian Neorealism before the screening of Umberto D. (1952) by Vittorio De Sica. Film critic Vernon Young stated that “no subject is important until awakened by art” when writing about the film. The story of Umberto D. resembles Wendy and Lucy (2008) by Kelly Reichardt, a touching film in which a homeless woman is struggling to make ends meet in America during the financial crisis. Her dog is her only friend, just like the dog of the retired Umberto, who is threatened to be kicked out of his social housing.

Week 48/2024

We suffer the diseases of our times. Kira Muratova directed a film set in the eleventh hour of the soviet era. Her film The Asthenic Syndrome was released in 1989, showing a society in which a strange disease is going around. The sufferer of the asthenic syndrome is caught between melancholy and indifference, a state that is endemic in the crumbling Soviet Union.

The second film of this week marks another decisive moment in history. Midnight Cowboy by John Schlesinger was released in 1969 and shows the other side of the iron curtain, where the dream of capitalism is slowly eaten up by disgracing precarity. The naïve Joe Buck leaves his job as a dishwasher in the American heartland to become a hustler in New York. The reality turns out to be different than imagined. He finds himself in a soiled room that he shares with his verminous buddy and part-time pimp, Ratso. In his text ‘New York Hollywood’, Dirk Lauwaert notes how Schlesinger films the environment of his characters in “an authentic, that is, reportage-style way”. He states: “Very important are the bridges that can be built between the environment and its residents. After all, how do you express this osmosis, at what level do you situate it, in what way do you let it become visible?”

In Kosmos (2014) by Ruben Desiere, set in the Brussels squat Gesù, the world floods in. Whistling through their fragile walls, a biting draft affects the dozens of families that live there. The inhabitants try to solve the cause of some mysterious incidents, a puzzle that is overshadowed suddenly when the building is evicted by immense police force in the dead of the night. Today, ten years later, Gesù still lies vacant. An uncanny wind grazes these cities and their ruins.

Week 44/2024

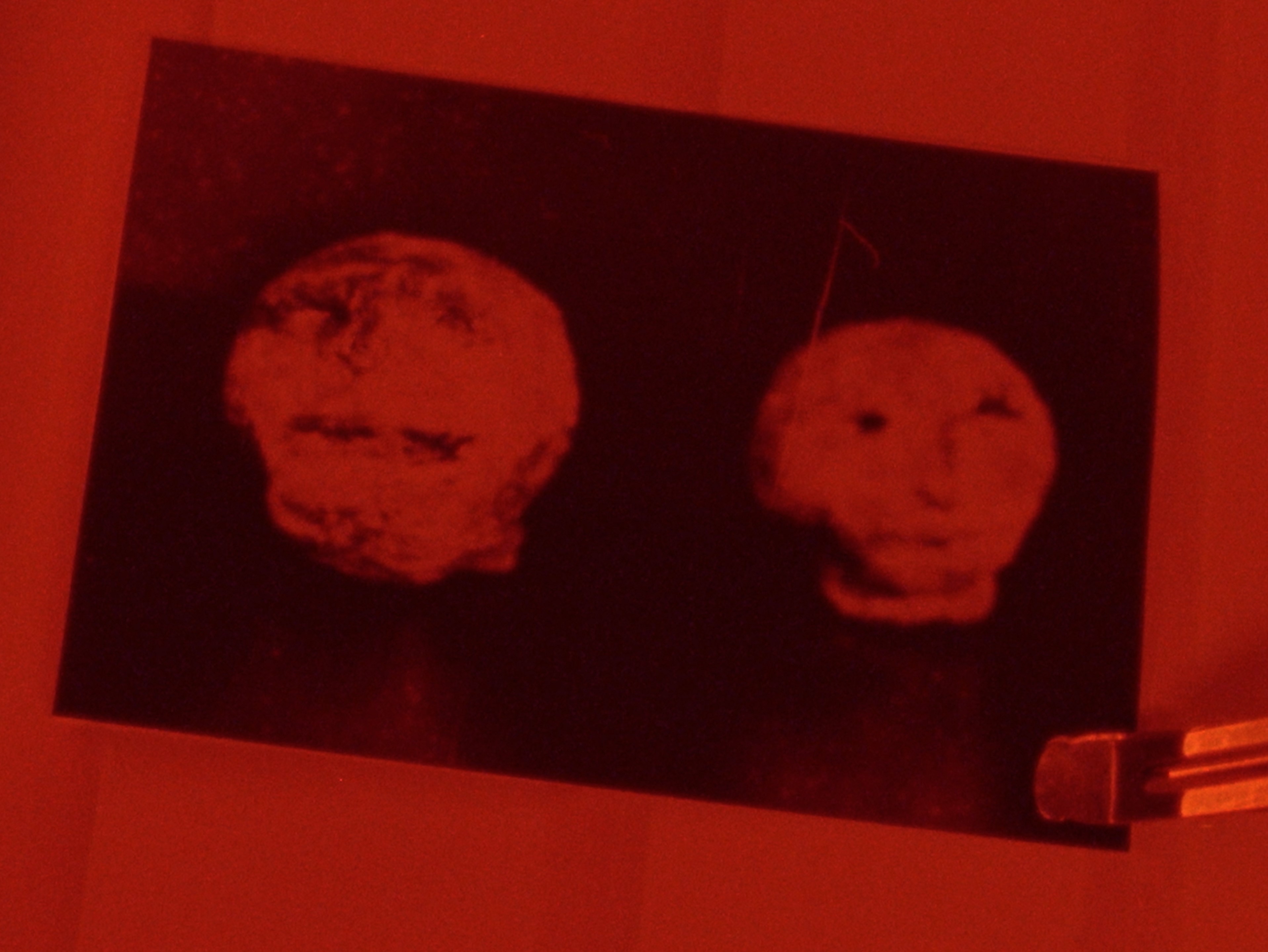

On Halloween, Belgian filmmakers Chloë Delanghe and Mattijs Driesen will present Hexham Heads, their co-directed film, at Art Cinema OFFoff. Their film is based on a ghost story deriving from the English town of Hexham, where a family was terrorized by a series of paranormal occurrences after bringing home some small stone heads. It is a re-account of this story and a re-imagination of the horror film genre, in which spaces, objects and the photographic process engender suspense. On this festive horror-evening, creators of the soundtrack Sam Comerford and Branwen Kavanagh will give a concert. After that, Delanghe and Driesen have chosen a surprise Halloween film to share with you.

In anticipation of this event, I asked these seasoned horror fans which other films they’d recommend. Their first choice is The Shining by Stanley Kubrick, stating: “The trope of the gloomy haunted house evoking a domestic trauma-psychology is transformed and expanded here into a gigantic, brightly lit hotel evoking a historic injury. This haunted space is defined by its labyrinthian corridors, in which time and place are confused, and wherein the violence of both psychology and history is continually repeated.”

Their second film of choice is Smile 2 by Parker Finn, who has declared The Shining his favourite film of all time and has cast Ray Nicholson, son of Jack Nicholson, in his latest instalment of the Smile franchise. “We haven’t seen this one yet, but we’re looking forward to it,” say Delanghe and Driesen. “The first one was far from great, but it had a truly weird ending. And even bad horror films always have interesting stakes.”

Week 39/2024

About 130 years after royal statues were robbed from the Kingdom of Dahomey, they are returning home. The French-Senegalese filmmaker and actress Mati Diop travels with them from the Quai Branly Museum in Paris to the port city Cotonou, Benin. In Dahomey (2024), Diop gives voice to the past by making the statues speak: “I am torn / between the fear that no one will recognize me / and the fear that I will no longer recognize anything.” In his article on Sabzian, Theo Warnier reflects on the longing for a place that is absent, articulated by statues that speak in Dahomey and in Césarée (1979) by Marguerite Duras.

Hyenas don’t talk; they laugh when stealing each other’s food. Senegalese filmmaker Djibril Diop Membéty wrote about the hyena: “It knows how to sniff out illness in others. And it is capable of following, for a whole season, a sick lion. From a distance. Across the Sahel. To feast one evening on its corpse. Peacefully.” In his film Hyènes (1992), an elderly lady returns to her hometown, causing a stir because she has become richer than the World Bank... A fable on greed and neo-colonialism, Hyènes is a film of stunning beauty.

In Bled Number One (2006), the director Rabah Ameur-Zaïmeche interprets Kamel, who is released from a French prison and then deported to his native Algeria, where he fails to feel at home. Paternalism and conservatism suffocate him, but he’s struck when observing the sacrifice of a bull. In the words of Ameur-Zaïmeche: “After the sacrifice, the meat is divided up into equal portions and shared out. That is inconceivable in Western capitalist society where exacerbated privatisation is the rule. It’s a big shock when you cross from Algeria to France. It takes generations to absorb.”

Week 20/2024

Frans van de Staak is a much-admired Dutch filmmaker, praised by Johan van der Keuken as, in his strongest moments, “the filmmaker that approaches the essence of filmmaking the closest.” Nevertheless, his films are hard to find, let alone to experience in a cinema. This week, you’re given the exceptional opportunity to watch his film Windschaduw (1986) on 16 millimetre at Art Cinema OFF off.

Another rare opportunity presents itself at BUDA, Kortrijk, where you can enjoy Flowers of Shanghai (1998) by Hou Hsiao-Hsien, an adaptation of the novel The Sing-song Girls of Shanghai (1892) by Han Bangqing, set in one of the most elegant brothels of Shanghai. Hsiao-Hsien said: “all that we want to do is capture that atmosphere and re-create it in a way that represents our imagination of Flowers of Shanghai, as well as all those other early vernacular novels we are familiar with.”

Patrick Leboutte is a film critic, teacher, but also a cyclophile. “Cinematography and the first cycle races are exactly contemporary: new means of transport. This is not a coincidence; these two arts being governed by the same Joule's law: every body in work generates energy and this in return makes the machine turn. This is the principle of cycling; this is also that of cinema. In both cases, it is a question of putting life into the mechanical.”

Leboutte will present a lecture on cycling and cinema, preceded by a ‘Tatiesque prologue’. Afterwards, he will introduce the cycling film Parpaillon (1993) by Luc Moullet: “If his film presents all the appearances of a true-false documentary, its burlesque approach to moving bodies clearly places it on the side of Jacques Tati, of whom I always thought he was the sole heir.”

Week 11/2024

In Equinox Flower (1958) by Yasujiro Ozu, the composition of a familial home is turned upside down when a father decides to arrange his daughter’s marriage. In Ozu’s films, the Japanese home with its sliding doors becomes the narrative space that can be delicately stirred by opening a vantage point or turning the gaze away, for instance, to the window.

In Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, the walls are solid and the windows show no sky. Jeanne Dielman fervently occupies herself with household chores, allowing no alteration of daily habits. Slowly, however, reality starts to resist: a shoe brush hits the floor. Ingrained gestures become corrupted. Chantal Akerman said in an interview: “Change is fear, change is opening the jail.”

In Stéphane Symons’s essay ‘Twee keer Ozu’ (‘Twice Ozu’), he quotes the Japanese culture critic Hasumi Shiguéhiko talking about “the threat of the destruction of the harmony of the whole” that is central to Ozu's cinema. This destabilization has everything to do with what Hasumi calls “meaningful details” that often “contradict the narrative structure”. Such details, gestures or events “pause the narrative flow” and constitute a “digression in the relationship with the intrigue”: they are “gaps.” In a new Dutch-language text on Sabzian, Dries Van Landuyt evokes how Jeanne Dielman has changed his way of looking at an ordinary plate in his hands: “Een krachtveld, een leegte die het bord samenhield, schemerde door de ogenschijnlijke massiviteit van het aardewerk heen. (A force field, a void that held the plate together, shimmered through the apparent solidity of the crockery.)”

The Moon and the Sledgehammer is a world apart from the interiors of the previous films. Philip Trevelyan made a cult documentary about a family that resisted modernity and remained in their forest south of London. Radically rejecting the prevailing curse of “push-button machinery” and the rigidity of the family home, they chose a shed in the ultimate messy constellation.

Week 4/2024

“Cities, like dreams, are built from desires and fears, although the thread of their discourse is secret, their rules absurd, their perspectives deceptive, and everything hides something else,” writes Italo Calvino in Invisible Cities (1972). How to write a line of history in the enmeshment of everyday desires and fears? Once one pulls a thread, the history of an entire country might emerge.

Bernardo Bertolucci made a big gesture when he created Novecento (1976), an epic starting from 1900 and leading to the Second World War. Two boys are born in Italy at the same time: one as landowner, the other as a peasant. As their friendship evolves, they take part in the class struggle. Film critic Joël Magny noted that “1900 can be read as a hymn to the people by a bourgeois, the adventure of a bourgeois who projects himself into the role of the proletariat by the means of a film”.

Kleber Mendonça Filho’s debut film, Neighboring Sounds (2012), takes place in the city where he was born, Recife. He stated in an interview that “99 percent of Brazilian filmmakers are middle class or upper middle class or bourgeois, as I am, yet most of the time they’re making films about people they don’t know that much about and subjects they haven’t mastered.” Focussing on one apartment building, he tells a story of changes in Brazilian society and scrutinizes the middle class, whose “feet never touch the ground.”

The last film of the week is Fearless (1993) by Peter Weir, who also brought us The Truman Show. An architect survives a plane crash, then walks through the streets of his hometown devoid of fear. But without fear, he will discover, there is no desire.

Week 47/2023

This week Sabzian will present No quatro da Vanda by Pedro Costa (2000). The film displays a rare virtuosity in depicting Vanda and her community of immigrants and drug addicts in a Lisbon slum. As the French philosopher Jacques Rancière wrote, Costa “placed himself in these spaces to observe their inhabitants living their lives, to hear what they say, capture their secret.” The film will be introduced by Gerard-Jan Claes.

In the other two films we selected this week, the obsessive and elusive artistic processes of a composer and of a filmmaker are explored. Olivier Messiaen et les Oiseaux (Denise R. Tual and Michel Fano, 1973) is a portrait of the French composer, organist and ornithologist who lived between 1908 and 1992. He was a devout Roman Catholic who honored the divine through his music. He acknowledged the beauty of the creation and birdsong in particular. Messiaen could be often found in a forest listening to birds and transcribing their songs.

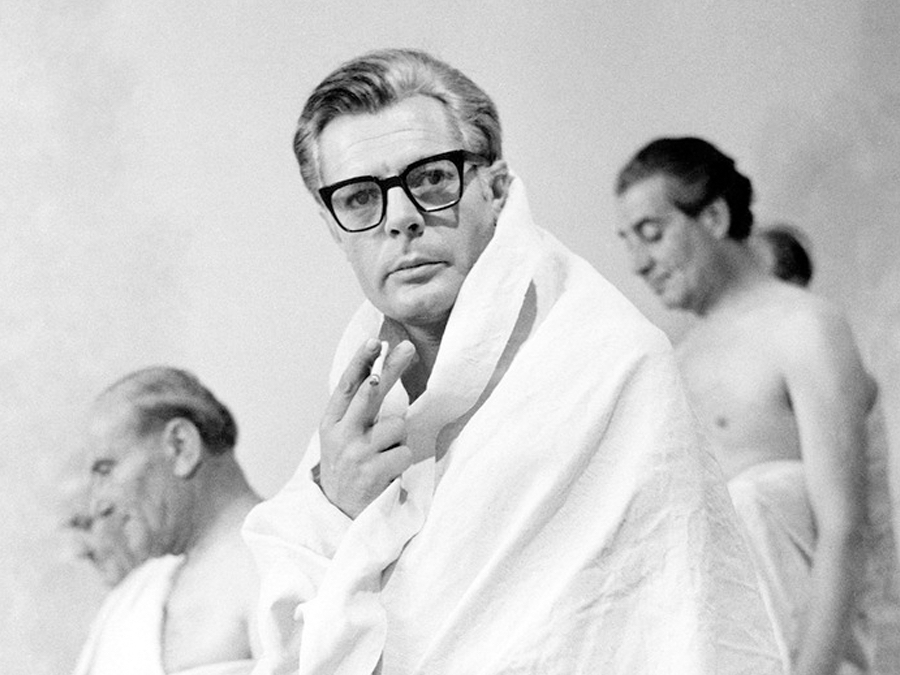

Federico Fellini’s Otto e Mezzo depicts the life of Guido, a film director. Memories of his youth, romantic entanglements and the confusion of a megalomanic film project parade in an exuberant filmic arena. As he struggles with writing a scenario, Guido is relentlessly attacked by the film critic Daumier. Peter Bondanella wrote in his book on Fellini: “As a corollary of his emphasis upon visualizing the moment of creativity, Fellini also provides in Otto e Mezzo a devastating critique of the kind of thinking that goes into film criticism, particularly the kind of ideological criticism so common in France and Italy from the time he began making films up to the moment he began filming Otto e Mezzo.”

Week 6/2023

This week, history is woven by a mother in Zerkalo [The Mirror] by Andrei Tarkovsky, she passes on the spell of heredity in Paix sur les champs by Jacques Boigelot, and a man becomes possessed by the history he deliriously pyrsues in Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, Zorn Gottes.

Zerkalo is a story of childhood that is intertwined with a collective history. For Tarkovsky, the mother is a figure that is strongly linked to time and history. The filmmaker himself stated: “The Mirror is not a casual title. The storyteller perceives his wife as the continuation of his mother, because wives resemble mothers, and errors repeat themselves – a strange reflection. Repetition is a law, experience does not get transmitted, everyone has to live it.”

The inheritance of spirit is the premise of Boigelot’s Paix sur les champs. In this film, a woman is the bearer of powers which make ‘errors repeat themselves’, but she’s capable to transcend them as well. In the Belgian countryside, the grandson of a presumed witch will find out how much his rural community still believes in the peril of his lineage when he falls in love with the sister of a girl who supposedly died under his grandmother’s influence.

Set during the expansion of the Spanish Empire in South America, the protagonist of Herzog’s film, Don Lope de Aguirre or ‘the Wrath of God’ as he calls himself, is a child of his times. Just like the Congo River in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, the Amazon leads him and his band further and further into the phantasm of colonialism. Accompanied by the hypnotic soundtrack by Popol Vuh, Aguirre dreams of becoming the founding father of an empire.

Week 7/2023

In this week’s selection, silence is brooding. Silence as a form of resistance, or as the effect of lovesickness; the inability to express oneself in the face of conflicting emotions.

In L’adolescente by Jeanne Moreau, a 12-year-old girl goes to visit her grandmother for the holidays. During her stay in the countryside, she slowly becomes disconnected from her childhood, perturbated by a budding love for an older doctor. Her personal transformation takes place in the wake of the Second World War. A changing political reality which silently yet disruptively weaves itself into her intimate story.

Le silence de la mer by Jean-Pierre Melville takes place merely two years after L’adolescente, but in an entirely different situation, namely after the occupation has taken place. In 1941, the Nazi-regime has consolidated itself and a German officer is stationed in a French family’s house. The only way the uncle and his niece can show resistance is by not speaking to him. But despite their silence, the officer talks to them, and the girl can’t shut herself off from listening. Little by little, the officer starts to stir the silence in her heart…

Pierre, Jan Decorte’s first film, depicts one day in the lonely life of a Brussels municipal clerk. Decorte wrote: “A human being is to another person an inextricable secret. The ultimate meaning and motives of most of the actions he performs remain hidden from him.” Pierre seems to act in an unmotivated way, and yet every single gesture contains a mystery. In the evening, Pierre addresses a woman from his sports-club, they talk briefly and he invites her home. It’s not the words they exchange that is remarkable, but their silences.

Week 42/2023

“Big ears listen with feet to the world as a jewel in the hand: it is night in America.” This sentence sounds like an exquisite corpse (cadavre exquis), but it consists, in fact, of the three film titles of this week that were all made last year.

Big Ears Listen with Feet was made by directing duo Ila Bêka and Louise Lemoine, whose films focus on the relationship between people and their surrounding architecture. In Bankok they followed Boonserm Premthada, who, deaf from birth, developed an architecture of the senses where sound vibrations become the voice of space. An architectural intervention closes space off to create intimacy and gives a tonality to all the emptiness it encompasses. If architecture is the organization of emptiness, then urbanism can be seen as a structuration of territory.

“Are animals invading our cities, or are we occupying their habitats?”, an animal caretaker sighs in It Is Night in America. Ana Vaz filmed in the Brasília Zoo, where stray wild animals are being taken care of. Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector once wrote: “Brasília is constructed on the line of the horizon. Brasília is artificial. As artificial as the world must have been when it was created. Brasília badly needs roaming white horses. At night they would be green in the moonlight.”

The World Like a Jewel in the Hand is an essay-film in which Arielle Aïsha Azoulay proposes a project of ‘unlearning imperial plunder’. As an Algerian Jew, she uses the camera to resist the extinction process of her culture and identity by the looting of objects that are still ‘held captive’ in museums and archives. By showing pictures, talking and singing, Azoulay and her collaborator, Nadia Ammour, propose a new form of historiography.

Week 37/2023

This week, we’ve selected three exciting film evenings that combine cinema, music and performance. This month and next, Cinema Nova in Brussels is presenting a focus on Iranian cinema, and a thematic film program on the relationship between humans and non-humans. During the Bestiarium Melting-Pot film evening, you will be treated to an “alcoholic lecture” by Dr. Lichic who will explain how to abandon your cumbersome canine companion during the holidays. After that, Laure Belhassen will present her bestiary of animal women. Femmes animales traces the history of depictions of women as animals. Finally, we will follow the artist duo Peter Fischli and David Weiss who, dressed up as a rat and a bear, have many adventures.

On 15 and 16 September, Monokino presents once again ‘SHHH’- a festival of silent films screened at the seaside, featuring work by Jasper Rigole, Isabelle Cornado, Helga Fanderl and many others. Film researcher Steven Jacobs will guide us through Ostend’s art and film history with an eye-catching film program. The starting point is Pour vos beaux yeux (1929) that Henri Storck made together with the surrealist Felix Labisse. We will see eyes and their gaze set against the backdrop of Belgian surrealism. Casper Jacobs will provide a live soundtrack.

German director and animation pioneer Lotte Reiniger is best known for her 1928 masterpiece The Adventures of Prince Achmed for which she cut the silhouettes herself and photographed them to make stop-motion films. Reiner's dreamy images find a musical pedant in Pak Yan Lau's free sound palette. This Brussels-based musician took some mysterious films such as Caliph Stork (1954) and The Magic Horse (1953) as a starting point and, while improvising with an arsenal of instruments and electronics, will perform a beautiful fairy-tale film concert for young and old.

Week 22/2023

This week, we are highlighting two film classics and one new release.

Night of the Hunter (1955) is Charles Laughton’s only film. He described it as a “sort of Mother Goose Tale”, but the film has influences of silent era expressionistic cinema, of film noir suspense, and of the musical. As Adrian Martin wrote, “it is as if the very fabric of the surreal universe created by Laughton is woven in and through the magical effects and properties of singing – especially when we reach the unlikely duet of Rachel and Powell, during their tense nocturnal stand-off, harmonising to ‘Leaning on the Everlasting Arms’ – one of the most disquieting and wondrous scenes in all cinema.”

Les Diaboliques by Henri-Georges Clouzot was released in the same year as Night of the Hunter. This film doesn’t feature a diabolical false preacher, but two infernal women instead: the wife and the mistress of a school principal who are both out for murder. The film similarly acknowledges the conventions of film noir, yet it disrupts them. According to Bosley Crowther, “it is a pip of a murder thriller, ghost story and character play rolled into one. (…) Everything seems to be set up for one of those ghastly little psychological tales of genteel mismating and frustration, when – bing! – the mischief begins.”

The latest documentary by Nicolas Philibert, Sur l’Adamant, will be released in Belgian theatres this week. With his crew, Philibert followed the patients and caregivers of a psychiatric day center called Adamant, which is situated on a boat floating on the Seine in the center of Paris. The first screening in Flagey will be in the presence of Linda de Zitter, clinical psychologist and founding member of Adamant.

Un point hors de l’arbre

The thirteenth episode of The Bandwagon, Sabzian’s irregular series of film-related mixes, by editorial member of Sabzian and filmmaker Nina de Vroome.

Week 16/2023

What does it mean to view filmmaking as a political act? Three filmmakers each approached militant cinema when they documented social struggle as an indictment, as a tool of contemporary historiography or as a laboratory of the future.

In 1976, Barbara Kopple listened to the radio and heard about a miners’ association in Harlan County, USA, that was fighting for the right to have a union. She loaned some money and went to film the Miners for Democracy. Kopple’s involvement in the movement was not only through filming. She said: “We wore machine guns with semiautomatic carbines.”

Combining political activism, film criticism and filmmaking, the practice of Brazilian Glauber Rocha as an artist and activist was intertwined. Black God, White Devil (1964) accounts the story of a man who kills his corrupt employer and becomes an outlaw who starts to venerate a violent, self-proclaimed saint. Stoffel Debuysere wrote that “in Glauber Rocha’s work, the myths of the people, prophetism and banditism, are the archaic obverse of capitalist violence, as if the people were turning and increasing against themselves the violence that they suffer from somewhere else out of a need for idolization.”

Relaxe (2022) is the first film of Audrey Ginestet, who is also a bassist in the band Aquaserge. The documentary is not about Aquaserge but about the band’s clarinetist, Manon Glibert, who was arrested in 2008 for ‘criminal association for the purposes of terrorist activity’, sabotaging high-speed lines in France. What came to be known as the group the ‘Tarnac Nine’ consisted of five women and four men who moved to a rural area in France in order to live communally, away from consumerist society. Audrey Ginestet made a portrait of Manon while she prepares herself for her trial.

Song of the Open Road

The fourteenth episode of The Bandwagon, Sabzian’s irregular series of film-related mixes, by editorial member of Sabzian and filmmaker Nina de Vroome.

Week 11/2023

This week we settle down at three screenings where cinema and film criticism meet.

KASKcinema in Ghent will screen Vivre sa vie: Film en douze tableaux by Jean-Luc Godard. In an article published by Sabzian, Frieda Grafe wrote: “The pre-formed units of meaning Godard inserts into his narrative are a kind of critical device, variants of both the theme and the way the film is shaped. It is a parody of the still ubiquitous essentialist separation of form and content.” The film will be introduced by film scholar Eduard Cuelenaere.

Eric de Kuyper, who plays an important role in Belgian film culture, will introduce the screening of Shanghai Express by Josef von Sternberg. De Kuyper characterises von Sternberg as a “paradoxical filmmaker”, who seemed to submit to each and every Hollywood cliché while managing to unmask them at the same time. The film will be followed by a discussion on de Kuyper’s work as a film critic. In the coming weeks, Sabzian will republish a number of striking texts from his remarkable oeuvre, with a new commentary by de Kuyper.

La terre de la folie by Luc Moullet will be shown at Cercle du Laveu in Liège, which is run by a collective of volunteers who created the conditions of a technically high quality cinema while inhabiting a social multi-usage space.

Moullet, former film critic for Cahiers du Cinéma, once wrote that “the filmmaker criticizes, and the critic praises.” Le Monde called the film “reminiscent of Luis Buñuel’s surrealist documentary Terre sans pain, revisited in this instance by the combinatory art of Georges Perec.”