“The help becomes more impertinent each day.”

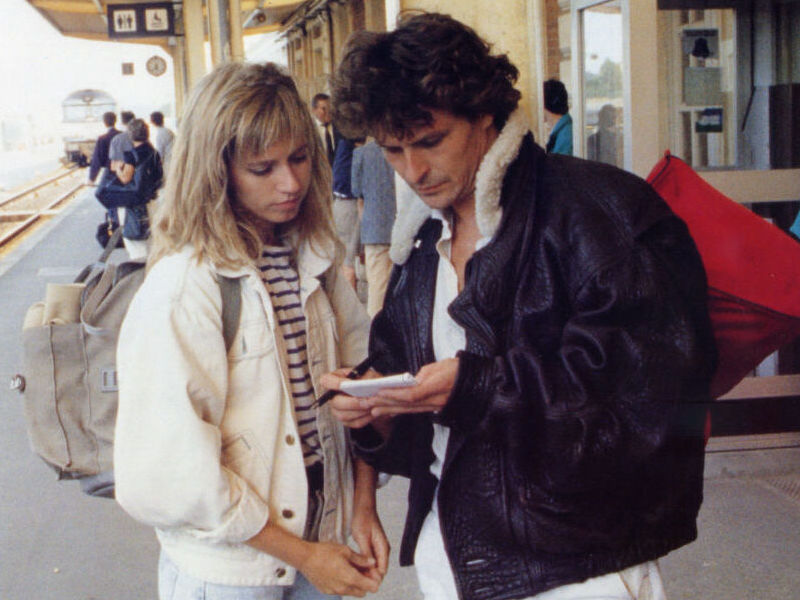

Julio Mayordomo, steward

“Nu is er die gapende opening van de salon naar de eetkamer, een verschrikkelijk groot gat waar iedereen tegelijk door kan weggaan – als ze het maar deden! De honger slaat toe. De dokter in het gezelschap verzucht dat als hij medicijnen had gehad, hij de oude heer had kunnen helpen, maar nu is het te laat. Iedereen verzamelt zich rond de stervende man. Die nacht wordt zijn lijk stiekem in een van de wandkasten verborgen. Zijn hand valt levenloos naar buiten. Het gezelschap heeft inmiddels zo veel tijd in de salon doorgebracht dat het ervan overtuigd is niet meer naar buiten te kunnen gaan. Het heeft de wilskracht om dat te doen verloren en daarmee ook meteen alle hoop om ooit in staat te zijn de stap naar de eetkamer te maken. Fatalisme slaat toe; een verliefd koppel begint te dromen over de dood.

[...]

Het thema van de handen keert steeds terug; de hand van de dode man die uit de kast glijdt, de handen van de geliefden die stiekem over elkaars boezem strelen, de hallucinante hand die zijn eigen leven leidt. Op een nacht kust een heer stiekem een dame op haar wang. Ze wordt schreeuwend wakker, maar is in de veronderstelling dat er iemand op haar hand ging staan. Het zijn allemaal verbeeldingen van de castratie van het handelen waar de gegijzelden aan lijden. Handen zijn beslissingsorganen; het woord dat verwijst naar het verrichten van een actie komt direct voort uit deze lichaamsdelen. Een hand kan door zijn eigenaar van alle kanten bekeken worden, hij kan als het ware voor zijn eigenaar poseren, alsof hij een eigen identiteit heeft. En wanneer de hand wordt getoond als een object, lijkt het alsof het personage de macht over zijn handelingen verloren heeft. In Un chien andalou (Luis Buñuel, 1929) blijkt de hand van een man hol te zijn. Hij bekijkt zijn hand met afschuw, want uit het gat in zijn handpalm kruipt een horde mieren. Zijn hand is een object geworden, het toneel van een handeling, maar is zelf het vermogen tot handelen verloren.”

Nina de Vroome

“So is the premise of the film so wholly inexplicable? Not for Buñuel: ‘basically, I simply see a group of people who couldn’t do what they wanted to do – leave a room’. As Buñuel himself admits, this dilemma, the ‘impossibility of satisfying a simple desire’, appears in many of his films. It just takes a variety of forms. The havoc wrecked by our internal drives and impulses, often entails a disturbance in time, to the point that time might even stand still. Time comprises different gears and moves faster or slower depending on many factors. Proust uses the metaphor of a car to describe how on any given day he will travel faster or slower depending on his mood: ‘there are mountainous, arduous days, up which one takes an infinite time to climb, and downward-sloping days which one can descend at full tilt, singing as one goes’. Without doubt, the inhabitants of the drawing room are subject to one steep and arduous climb. Time dilates with each movement and contracts with every configuration; expanding from the moment they find they can’t leave, extending into months of incarceration until the guests miraculous reassembly into the places they held when the nightmare first began.

Arturo Ripstein was on set as an aspiring 18-year-old filmmaker observing Buñuel direct. Buñuel was moving everyone around the set like chess pieces; he knew precisely what he was doing although nobody else did. Ripstein explains it this way: ‘Time was abolished so only space happened in this film. Time was just a circle and when space becomes time the thing is solved.’ So once they realise they have unwittingly returned to the same positions they occupied when their confinement began, we see them again as they were before; we can even show them now side-by-side, with a slight variation in camera angle that Buñuel would insist upon, punctuating the fact that it’s not an exact repetition. What is striking when we do this is how the ‘originary’ undercurrents of social existence are revealed not after a long interval, wherein social practices slowly unravel to reveal the primitive urges underneath, as in Lifeboat, but at one and the same time. Social convention, and indeed religious belief, cannot save us from this fact.”

Mairead Phillips