Atteyat Al-Abnoudy

Out of the Shadows

A Conversation with Atteyat Al-Abnoudy

A Conversation with Atteyat Al-Abnoudy

A Conversation with Atteyat Al-Abnoudy

A Conversation with Atteyat Al-Abnoudy

I don’t want to be labelled a women’s filmmaker because I make films about life, and women are only a part of this life. I make films about people who I know, who I relate to (class-wise speaking) – humble and poor people. About their struggle to live, about their joy, and about their dreams. I still learn from them, from what they are doing and of their wisdom about life. I give the floor to my people to speak out. That is why they call me ‘the poor people’s filmmaker’.

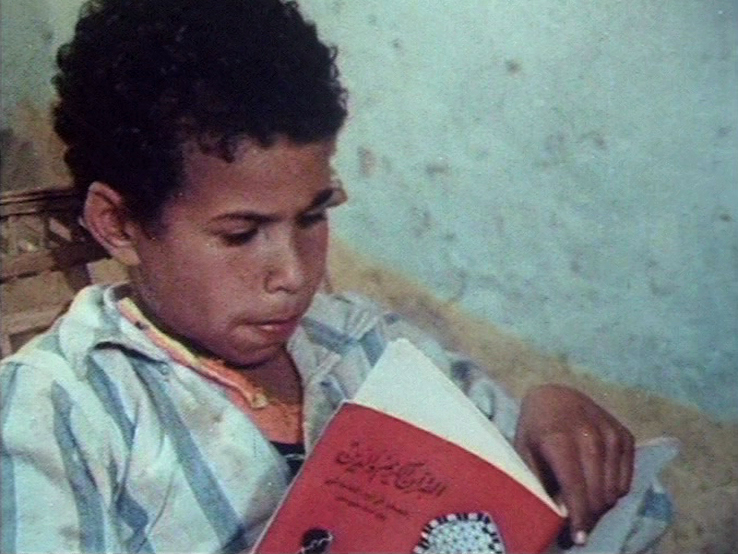

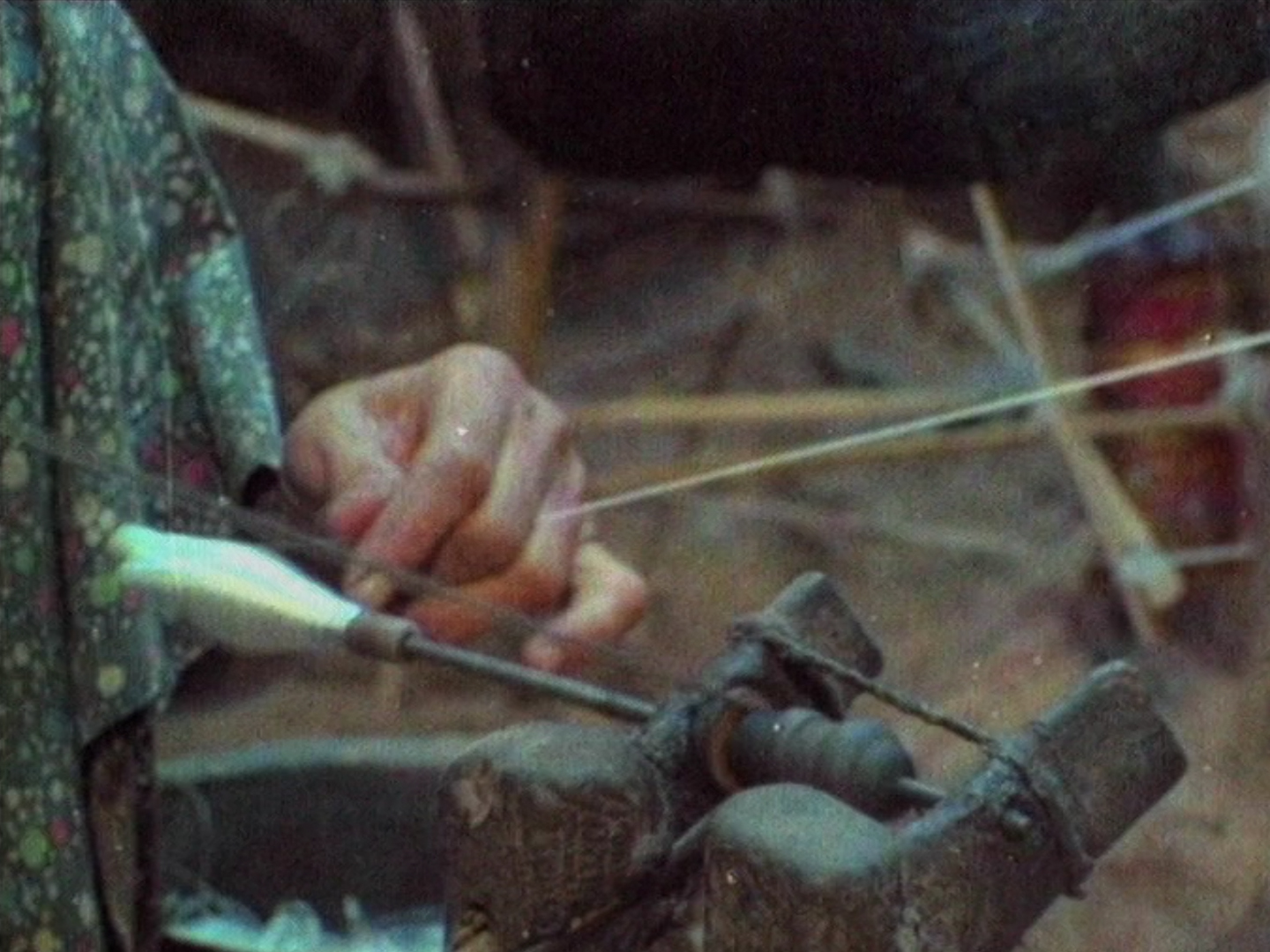

Atteyat Al-Abnoudy (1939-2018) was born Atteyat Awad Mahmoud Khalil into a family of labourers in a small village along the Nile Delta. A child of Nasserism, she studied law at the University of Cairo while supporting herself financially by working as an actress and assistant director at the theatre. At the beginning of the 1970s, she decided to study film at the Cairo Higher Institute of Cinema, where she created Horse of Mud, which was not only her first film but also Egypt’s first documentary produced by a woman. Her graceful focus on the disadvantaged and the unrepresented in Egyptian society would earn her the nickname “the poor people’s filmmaker”, but it also enkindled a confrontation with censorship. “The censors didn’t like to show the people as very poor after twenty years of revolution in Egypt. They think cinema, especially documentary, should be propaganda for the state. In a way, it’s the fault of the filmmakers who were making documentaries over the past twenty years. They made at least eleven films about the construction of the Aswan High Dam, but they spoke only about the machines, the tractors, the engineers. Nobody talked about the working people who died and suffered to help build this Dam.” Despite its limited circulation, Horse of Mud went on to win numerous international prizes, after which Al-Abnoudy made her graduation film, The Sad Song of Touha, a portrait of Cairo’s street entertainers — which she created in collaboration with her husband, poet and song- writer Abdel Rahman Al-Abnoudy. She continued her studies at the International Film and Television School in London until 1976 and persisted to document the daily lives and struggles of economically and socially marginalized groups in Egypt, while exposing the structural inequalities within the socio-economic system. In films such as Permissible Dreams (1983) and Democracy Days (1996), she attended to the lot of Egyptian women, a choice of subject matter which has fre- quently invited the displeasure of government authorities. Against the grain, Atteyat Al-Abnoudy managed to produce more than thirty films which were shown worldwide, albeit rarely in her own country. Before her death in 2018, she left her film estate to the Cimatheque — Alternative Film Centre in Cairo, which continues to advocate her legacy of independent and committed filmmaking.