Jocelyne Saab

Out of the Shadows

Interview with Jocelyne Saab

Interview with Jocelyne Saab

Interview with Jocelyne Saab

Interview with Jocelyne Saab

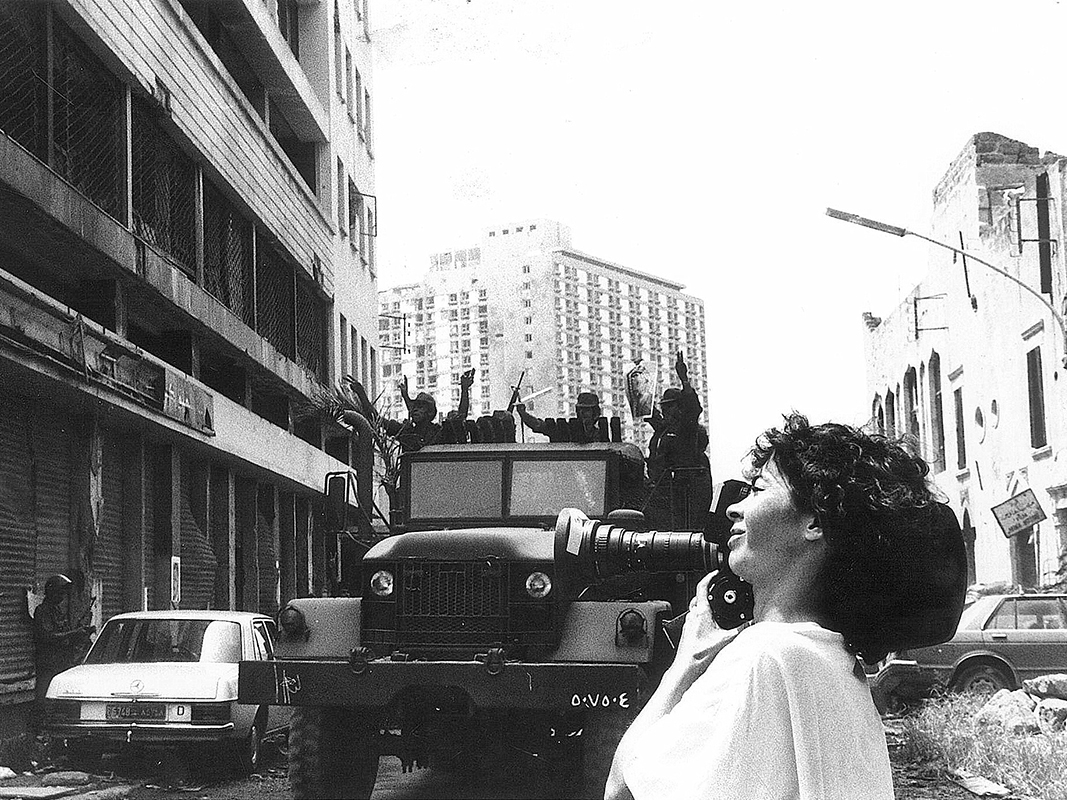

Once you’re holding a camera, it’s your profession that matters...Maybe, as a definition, and fundamentally I don’t know, you react with a gaze that doesn’t linger on the surface of things, of guns or armies; I have always preferred getting to know people’s sensibilities in great detail, the children, the women, the men, the daily life of human beings... In this field, people are so surprised to see a woman arrive on set that they make room for her and respect her.

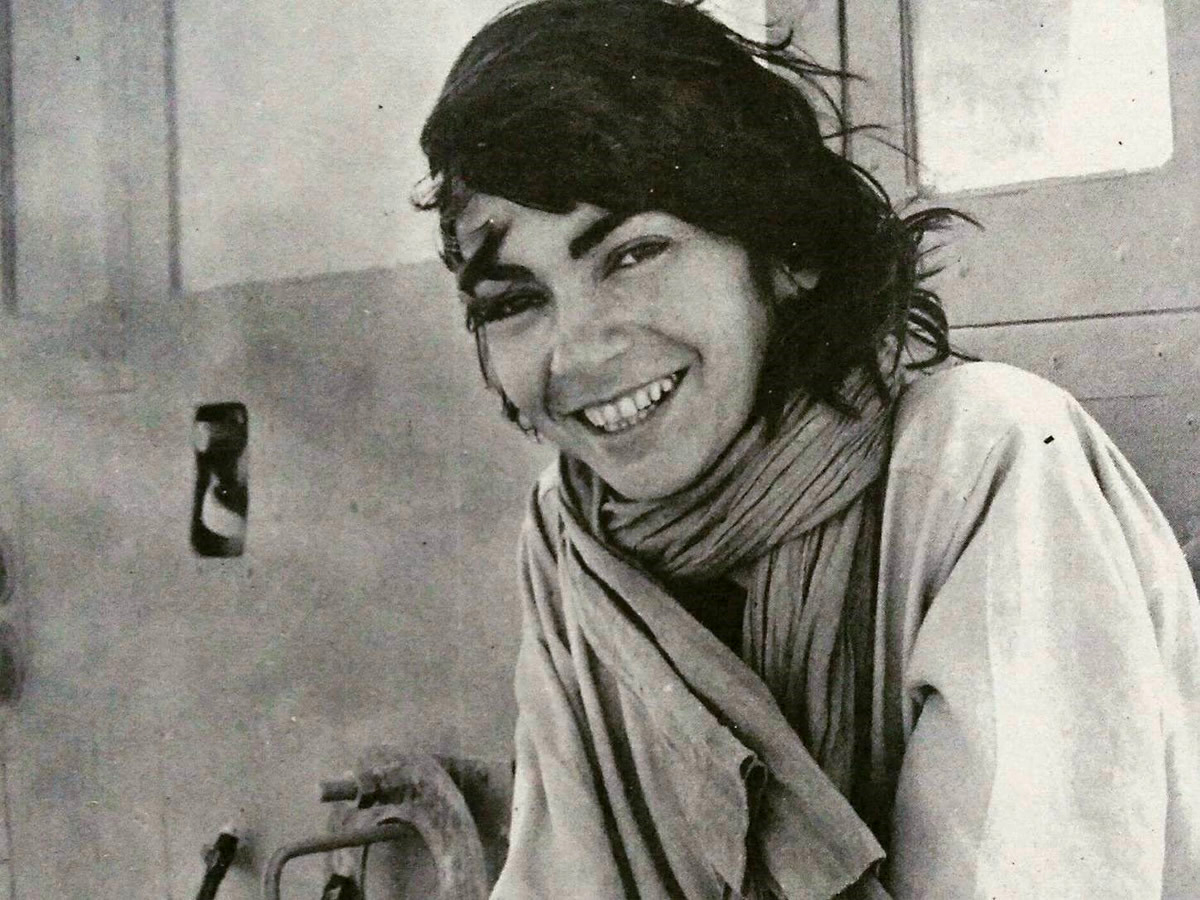

Jocelyne Saab (1948-2019) was born and raised in Beirut. After completing her studies in economic sciences at the Sorbonne in Paris, Saab worked on a music programme on the national Lebanese radio station before being invited by poet and artist Etel Adnan to work as a journalist. Unlike most war reporters, who must travel to war zones to pursue their profession, war came to Saab’s native Lebanon in 1975, and that same year saw the beginning of Saab’s filmmaking career with Lebanon in a Whirlwind, an account of the various forces and interests behind the incipient conflict. The war would last another 15 years, and Saab’s chronicling of its horrors — particularly in her remarkable “Beirut Trilogy”, comprising Beirut, Never Again (1976), Letter from Beirut (1978), and Beirut, My City (1982) — is unequalled in both its ethical integrity and emotional impact. The same candour and empathy Saab applied to the war in her homeland can be found in her other documentaries. Filming the struggle of the Polisario Front in the desert of Western Sahara, the consequences of the infitah on Sadat’s policy in Egypt, or the aftermath of the Iranian revolution of 1979, a picture of a Middle East removed from reductive simplifications emerged through the polyhedral prism of her camera. “I believe that what makes up the specificity of my trajectory is that I have always wanted to remain coherent; I have always been ready to fight for what I believe in, to show and analyse this changing Middle East that I’m so passionate about. Yet the day came when I grew tired of it, or rather my eyes grew tired. I couldn’t see anything anymore — there had been too many deaths and too much suffering. I then moved on to fiction.” Her entry into fiction filmmaking came in 1981 when she worked as second unit director on Volker Schlöndorff ’s Circle of Deceit. Shortly after that, she directed her first fictional work, A Suspended Life (1985), set in the same war-torn Beirut she had documented ten years prior. After the war reconfigured the whole country, in Once Upon a Time in Beirut (1994), Saab tried to rescue the cinematographic memory of the Lebanese capital in the same year that cinema turned 100 years old. In 2005, she was censured and her life threatened for making Dunia, Kiss Me Not On The Eyes, a film shot in Cairo about desire, pleasure and female sexuality in the context of Islam. Until her death in January 2019, Jocelyne Saab remained devoted to what she called her “two permanent obsessions: liberty and memory”.