A young boy, left without attention, delves into a life of petty crime.

EN

“Allowing a victimised child to be less than wholly sympathetic – in ways that only a real-life child could ever be – Truffaut consolidates The 400 Blows as an act of rebellion. It is not just Antoine who is a rebel, or Truffaut on whose early life the film is based. The film, in its conception and mise en scène, constituted an all-out rebellion against the established tenets of French cinema. As a young critic for Arts and Cahiers du cinéma, Truffaut had railed savagely against films in the ‘Tradition of Quality’ – those glacially elegant literary adaptations that dominated French production in the ’40s and ’50s. His most brutal and notorious review had been of Chiens perdus sans collier (Jean Delannoy, 1955), which had tackled the problem of delinquent minors: ‘Chiens perdus sans collier is not a failure. It is a crime, perpetrated according to certain rules… [and] set to images by a man who lacks the intelligence to be a cynic, who is too corrupt to be sincere, too pretentious and solemn to be simple, Jean Delannoy.’ This particular piece of journalism had earned Truffaut a solicitor’s letter from the director – one of the most prominent and successful figures in the French cinema of the day. Never a man to grovel or eat his words, Truffaut further ridiculed the film in his 1957 short Les Mistons. Spotting a poster that advertises Chiens perdus sans collier, the anarchic and half-wild urchins of the title gleefully tear it from the wall.”

David Melville1

Anne Gillain and Dudley Andrew: The consensus about Truffaut is that he makes films of the past in the present because of his autobiographical inspirations. It starts with Les 400 coups, of course.

Arnaud Desplechin: Autobiography is certainly part of it, but the film mixes in Hitchcock’s life as well! The famous story of Hitchcock’s father bringing his son to the police station when Hitch was five. … That’s what strikes me at the beginning of the scene in Les 400 coups, when the father takes his own son to jail. We see angels rotating in two large store windows because it’s Christmas time. It’s like a sort of odd fairy tale, because of these department store windows. So is it a fairy tale or not? I love the father’s character, how nice he is. There’s nothing really mean about him. Truffaut must have asked himself: so how can I tell this story without being judgmental about my characters? If there’s something awful, it’s just because of the plot, because what’s happening to the young boy is awful; but there is no general evil, certainly not in this man who is really lost, though he’s sure he is doing the right thing. So it’s not just a mean father putting his son in jail. Sure there is Truffaut’s personal involvement since he is using part of his life, but there is also a strong cinephilic commitment because he’s doing it à la Hitchcock. After that opening the jail scene becomes so simple, just a documentary … plus.

Dudley Andrew and Anne Gillain in conversation with Arnaud Desplechin2

“François Truffaut’s life has always been a fertile source for his cinema, an original material, a sort of fictional treasure, the common thread that linked the high points of his life. From Les quatre cents coups, the filmmaker is undeniably the child of his oeuvre, inventing the story of his origin through the character of Antoine Doinel, who is both himself and already another, since this child of cinema belonged to everyone from the outset. And his work was also the product of his childhood, not to say the child of his childhood. In this regard, Claude Chabrol states a simple truth: “François’s youth was more interesting than that of others. If I had told the story of my youth, I wouldn’t have made more than two films!””

Antoine de Baecque and Serge Toubiana3

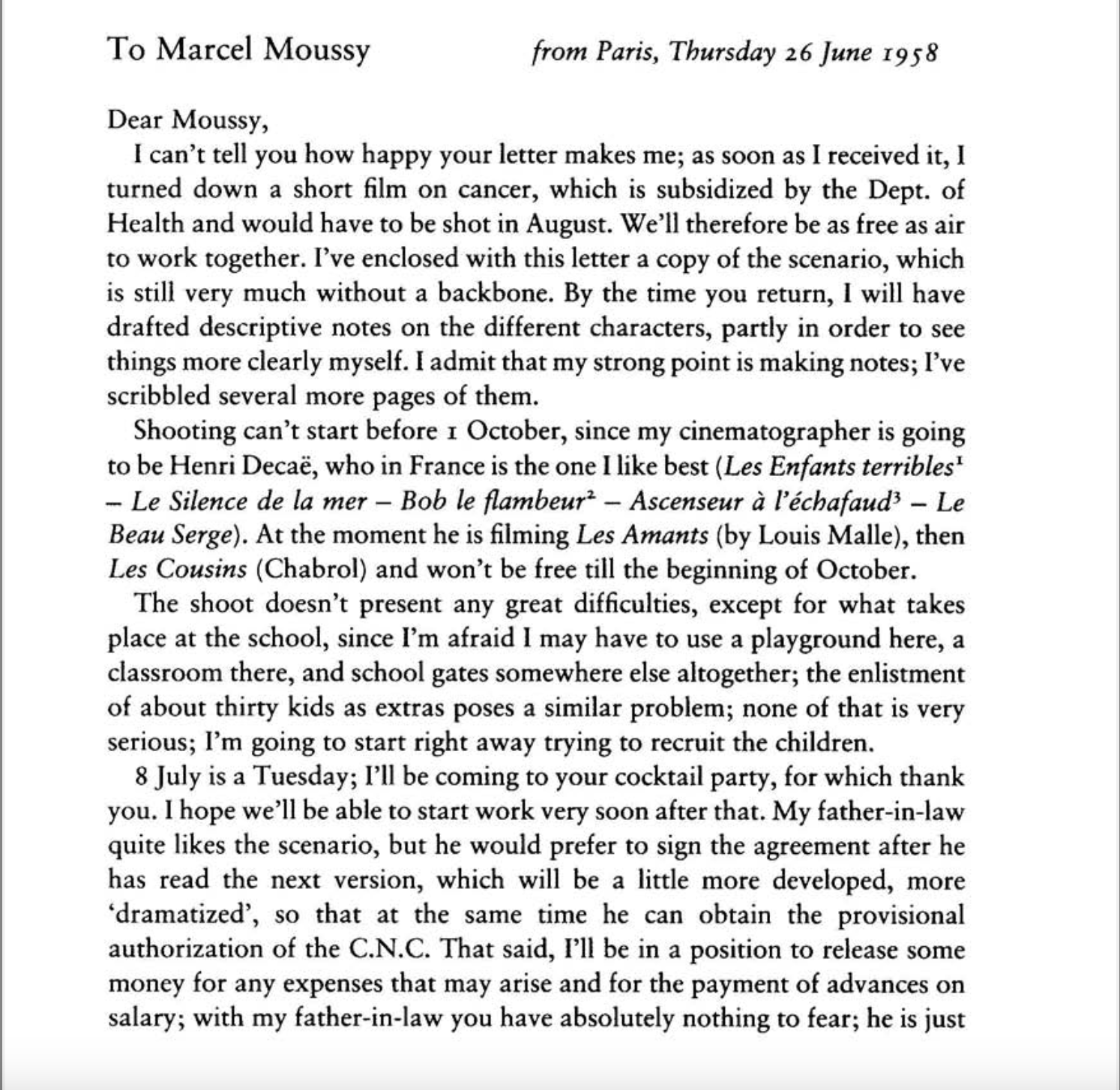

Jean-Pierre Léaud's Audition for Les quatre cents coups

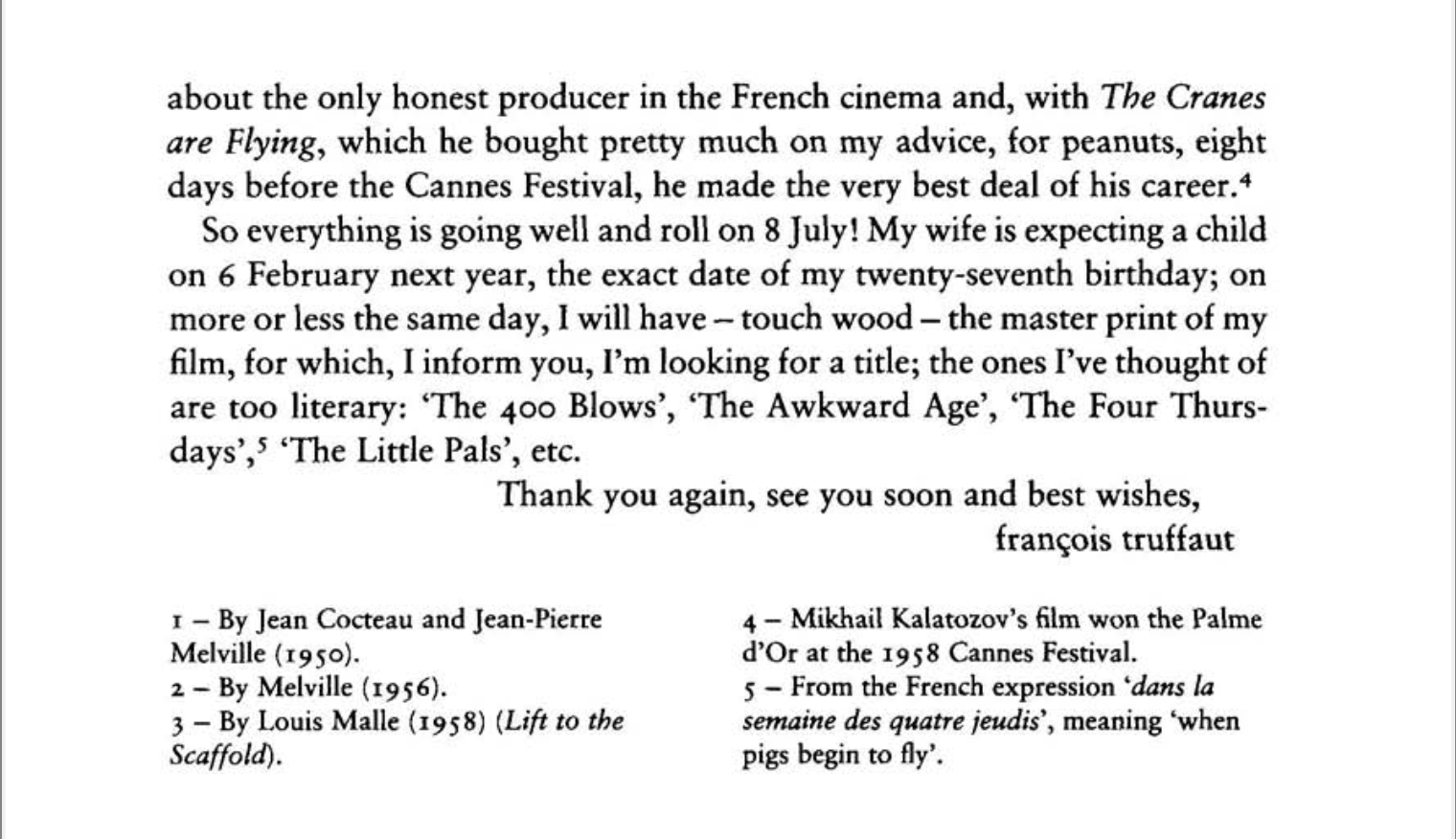

Jean-Pierre Léaud at the 1959 Cannes Film Festival for Les quatre cents coups

- 1David Melville, “Children of the Revolution – Truffaut and Les quatre cents coups,” Senses of Cinema, July 2014.

- 2Dudley Andrew and Anne Gillain, A Companion to François Truffaut (Chichester: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2013).

- 3Antoine de Baecque et Serge Toubiana, François Truffaut (Paris: Gallimard, 1996) [translation by Sabzian].

FR

« La vie de François Truffaut a toujours constitué pour son cinéma une source féconde, un matériau originel, une sorte de trésor fictionnel, le fil rouge qui permettait de relier entre eux les moments forts de son existence. Dès Les quatre cents coups, le cinéaste est indéniablement l'enfant de son œuvre, inventant le récit de son origine à travers le personnage d'Antoine Doinel, qui est à la fois lui-même et déjà un autre, puisque cet enfant de cinéma appartint d'emblée à tout le monde. Et son œuvre fut aussi le produit de son enfance, pour ne pas dire l'enfant de son enfance. À ce propos, Claude Chabrol énonce une vérité toute simple : « La jeunesse de François était plus intéressante que celle des autres. Moi, si j'avais raconté ma jeunesse, je n'aurais pas fait plus de deux films! » »

Antoine de Baecque et Serge Toubiana1

- 1Antoine de Baecque et Serge Toubiana, François Truffaut (Paris: Gallimard, 1996).