Passage: Mehdi Jahan

“Still, these images will haunt us in dreams and call on us; so that we may come and meet them, though no longer with the duty of having to follow the trajectory imposed by the text. (…) To take a term frequently used by painters: these images are ‘fixatives’, once isolated they serve no function. They should not, yet here they are, carrying their ‘expressive charge’. They persist in memory, beyond the text. They live their own lives.”

Raúl Ruiz1

My late paternal grandparents were Sufi oral storytellers in the village of Kalitakuchi, located in the northeastern state of Assam in India. They integrated fragments from the dreams, recollections, and lived experiences of the residents of their village into their discursive and circular tales. They firmly believed that the fragments that make up a narrative had an autonomous existence and may freely merge with fragments from other stories to generate an infinite stream of stories. Over time, I have come to understand that my relationship with film viewing and filmmaking is pretty much the same.

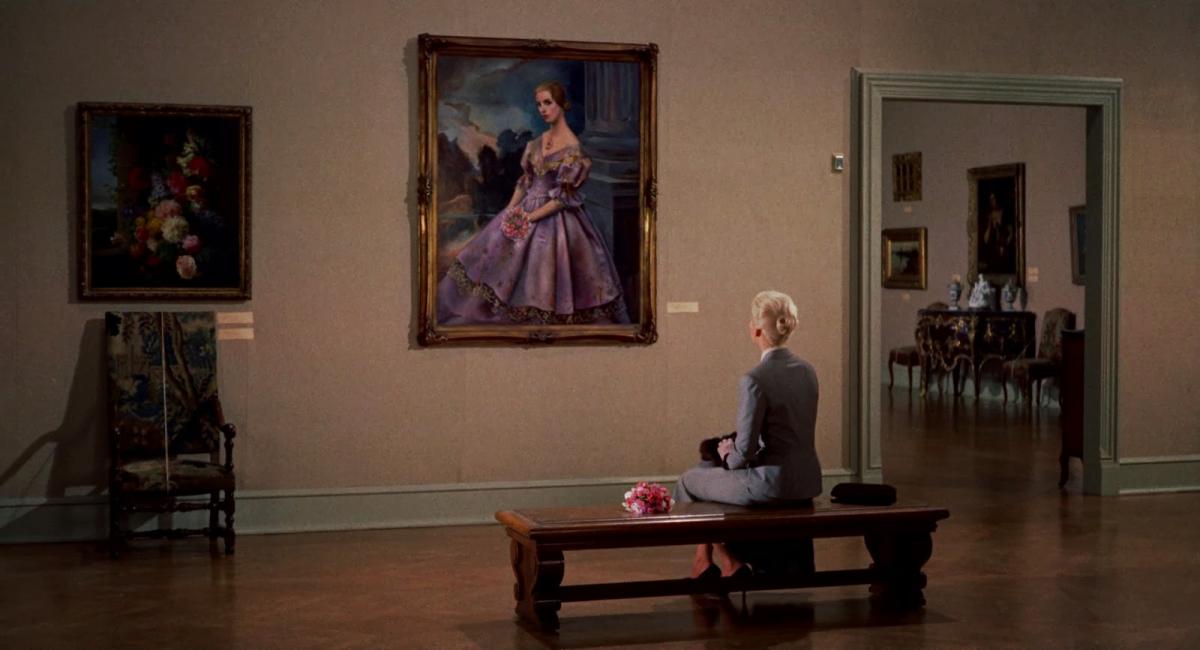

In that sense, Raúl Ruiz’s words resonate with me as they affirm my association with cinema as a cinephile and filmmaker, as well as the dialogue between the history and collective memory of my region. We live in an era of enormous profusion of images, a proliferation which in turn reconfigures our very relation to cinema. Not only do films themselves irrigate the landscapes of our cinematic memory, but so do our regular encounters with filmic objects – such as screenshots from films shared by cinephiles on social media. Images from films are constantly being distilled in our mind, where they intertwine with memories from our own lives, perpetually generating new narratives. It’s not so much the act of watching films as it is the images from films that linger in our memory thereafter that pushes cinema into the realm of dreams. In our memories, images, become pregnant with infinite possibility. For instance, I often imagine Carlotta Valdes sitting at a gallery admiring Laura’s exquisite portrait, while Nana Kleinfrankenheim clutches the hand of her lover Antoine Doinel inside a cinema hall, grieving over the last scene of Agnes Varda’s Vagabond. In the copious stream of encounters and associations, cinephiles inevitably discover their own portraits. Indeed, as fervent cinephile Frank Beauvais’s magnificent film Just Don’t Think I'll Scream (2019) has shown, a film made exclusively of images from other films can also be an intensely intimate, deeply personal document.

In a recurring dream, I find myself roaming inside a structure resembling the Tower of Babel (let’s call it “The Tower of Lumiere” or “The Tower of Light”), where images from all the films ever made and ever will be made are scattered around freely, like cells in a body. I navigate the structure, constructing my own films in the process. On the tower’s enormous screen, however, when I project the film made up of images from the past, present, and future of cinema, I somehow see scenes from my own life as if it were a home movie. Apart from being so life-affirming, the dream induces ruminations on the tragedy of cinema – the fact that it strives to be more real than reality itself. Cinephiles are essentially vagabonds at best and exiles at worst, the only place we can truly call “home” is the reality that cinema offers. A home where, much like the history of cinema, time is circular and simultaneous – as if the train is still arriving at La Ciotat station as Godard sets up the first shot of Goodbye to Language. Cinema persists in my memory, living its own life.

- 1Raul Rúiz, Poetics of Cinema 2, trans. Carlos Morreo (Paris: Editions Dis Voir, 2007).

Image (1) from Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958)

Image (2) from Les quatre cents coups (François Truffaut, 1959)

Image (3) from Vivre sa vie: Film en douze tableaux (Jean-Luc Godard, 1962)

Image (4) from Sans toit ni loi (Agnès Varda, 1985)

In its section Passage, Sabzian invites film critics, authors, filmmakers and spectators to send a text or fragment on cinema that left a lasting impression.