A heavily disfigured man is displayed as a freak to create horror and astonishment. After being rescued by a Victorian surgeon, his monstrous façade slowly reveals a person of kindness, intelligence and sophistication.

“When someone laughs, or cries, or even speaks their lines in a Lynch film, we wonder, instinctively, what it means for a body to produce such a sound or convulsion; when someone dances, or sways, or even walks, we are confronted with the quasi-mechanical strangeness of all human movement, figuring itself out (not always successfully) in the synaptic exchanges between body and brain.”

Adrian Martin1

“The more the elephant man is popular and celebrated, the more the ones visiting him have the time to put on a mask, a mask of politeness that conceals what they feel at his sight. They go see John Merrick to test this mask: if their fear betrayed them, they would see its reflection in Merrick’s eyes. It is in this way that the elephant-man is their mirror, not a mirror where they could see and recognize themselves but a mirror to learn how to play, how to conceal, how to lie even more. At the beginning of the movie, there was the abject promiscuity between the freak and the man showcasing him (Bytes), then Treves’ muted, ecstatic horror in the cave. At the end, it is Mrs. Kendal, the London theatre star, who decides, when reading a newspaper, to become the elephant man’s friend. In a rather uneasy scene, Anne Bancroft, as the guest star, wins her bet: not one muscle of her face twitches when she is introduced to Merrick, to whom she talks as to an old friend, going as far as kissing him. The loop has closed, Merrick can die and the movie can end. On one hand, the social mask has been entirely reconstituted; on the other hand, Merrick has at last seen in another’s gaze something totally different than the reflection of the disgust he inspires. What? He couldn’t say. He takes the height of artifice for the truth and of course he’s not wrong—since we are at the theatre.

For the elephant man cultivates two dreams: to sleep on his back and to go to the theatre. He will realize them both the same evening, just before dying. The end of the film is very moving. At the theatre, when Merrick stands up in his box to allow those who applaud him to see him, we really no longer know what is in their gaze, we don’t know what they see. Lynch has then managed to redeem one by the other, dialectically, monster and society. Albeit only at the theatre and only for one night. There won’t be another performance.”

Serge Daney2

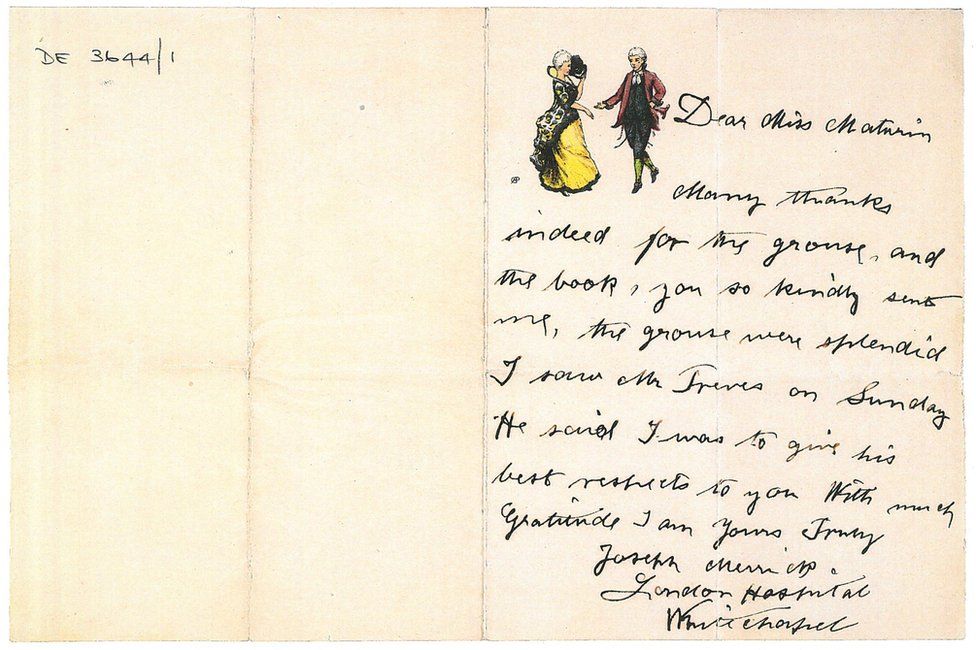

The only known surviving letter from Joseph Merrick, known as the Elephant Man. The letter was written to a young widow called Leila Maturin, who was said to have been the first woman to smile at him …

- 1“The Havoc of Living Things,” The Third Rail, 6.

- 2“The Monster is Afraid: The Elephant Man, David Lynch,” CinemaScope.