Texts

Every Wednesday, Sabzian publishes texts on cinema in Dutch, English or French.Chaque mercredi, Sabzian publie des textes sur le cinéma en néerlandais, en anglais ou en français.Elke woensdag publiceert Sabzian teksten over cinema in het Nederlands, Engels of Frans.

Francis Alÿs’ Children’s Games

There’s something unsettling about the chaos of children playing; there’s a lot of yelling, screaming, and shouting, and it always takes a bit before you can determine if it’s innocent enthusiasm or if intervention is required. The energy of a playground oscillates between passionate zeal and rowdy excitement, where deep concentration silently creeps in between. When we let the commotion wash over us and watch a screen, we see that children take their play very seriously.

Francis Alÿs’ Children’s Games

De chaos van spelende kinderen heeft iets verontrustends; er wordt veel geschreeuwd, gegild en geroepen en het duurt altijd even voordat je kunt inschatten of het om onschuldig enthousiasme gaat of dat er een interventie noodzakelijk is. De energie van een speelplaats oscilleert tussen passionele geestdrift en baldadige opwinding, waar diepe concentratie stilletjes tussendoor sluipt; wanneer we het rumoer om ons heen laten spoelen en een scherm bekijken, zien we dat kinderen hun spel heel serieus nemen.

I have constructed narratives to awaken the viewer’s emotions, feelings of anger and joy. These emotions have a power that can be tapped and directed so that people become actively involved in changing themselves or their world. My films’ upbeat endings represent the collective wish of those involved to show that things can work out. It’s not to give directions for a mass movement nor establish models but rather to create an atmosphere of hope and courage.

Les fabulations collectives d’Adirley Queirós et Joana Pimenta

À l'occasion de la rétrospective « Chants et flammes : les fabulations collectives d’Adirley Queiros et Joana Pimenta » lors de la 35e édition de FIDMarseille cette année, Louise Martin Papasian, membre du comité de sélection de FIDMarseille, présente les films des réalisateurs brésiliens Adirley Queirós et Joana Pimenta. La rétrospective se poursuivra à Paris du 5 au 8 juillet, lorsque FIDMarseille reprendra à la Cinémathèque Française.

The Collective Fabulations of Adirley Queirós and Joana Pimenta

On the occasion of the ‘Songs and Flames: The Collective Fabulations of Adirley Queirós and Joana Pimenta’ retrospective at the 35th edition of FIDMarseille this year, Louise Martin Papasian, a member of the FIDMarseille selection committee, introduces the films of Brazilian filmmakers Adirley Queirós and Joana Pimenta. The retrospective will continue in Paris from July 5 to 8, when FIDMarseille resumes at the Cinémathèque Française.

Over Wang Bings Man in Black (2023)

De vorm – hoe te spreken – kan een daad van verzet zijn. Zo moet Man in Black ook begrepen worden. “One can describe many things but the moment one describes pain, language begins to falter.” Aanvankelijk lijkt het alsof Wang Xilin zijn spraak is verloren. Zijn lichaam spreekt en hij loeit, met de tranen over zijn wangen. Wanneer hij eindelijk zijn woorden terugvindt, wanneer hij kan beschrijven wat hem is overkomen dan is het niet de emotie maar de muziek die hem overstemt. Niet omdat wat hij zegt onzinnig, langdradig of herhaling is. Neen, we zien de man praten en lezen zijn woorden in ondertiteling, begeleid door luide muziek. Het moment geeft ons toegang tot de transitie, dat wat zich tussenin bevindt. Tussen het onzegbare en de woorden als placeholders van de pijn.

The Work of Cyrus Frisch

Recently, three films by Cyrus Frisch have become available through Video on Demand: Why Didn’t Anybody Tell Me It Would Become This Bad in Afghanistan (2007), Blackwater Fever (2008), and Oogverblindend [Dazzle] (2009). Upon the release of the latter film, de Filmkrant wrote that the Netherlands had “at least one director who has a disdain for conventions and fully seeks controversy.” Among Frisch’s admirers are Gaspar Noé and Guy Maddin. The director is currently working on Finally! How a Piece of Wood Managed to Save Us All [working title], part of a comprehensive and ambitious project to address world problems through a series of narrative features. In anticipation of the World Problems Project, now in the pipeline, the present article offers a sketch of a filmmaker who once believed that the best way to initiate a debate on ethics was to operate unethically.

Het werk van Cyrus Frisch

Sinds kort zijn drie films van Cyrus Frisch beschikbaar via Video on Demand: Why Didn’t Anybody Tell Me It Would Become This Bad in Afghanistan (2007), Blackwater Fever (2008) en Oogverblindend (2009). Bij het uitkomen van die laatste film schreef de Filmkrant dat Nederland “ten minste één regisseur rijk [is] die een broertje dood heeft aan conventies en volop de controverse zoekt”. Tot zijn bewonderaars mag Frisch onder anderen Gaspar Noé en Guy Maddin rekenen. Momenteel werkt Frisch aan Finally! How a Piece of Wood Managed to Save Us All (voorlopige titel) als onderdeel van een omvattend en ambitieus project om wereldproblemen via een reeks speelfilms te behandelen. In aanloop naar het World Problems Project dat in de pijplijn zit, een schets van een filmmaker die ooit meende dat je het beste een debat over ethiek kunt uitlokken door onethisch te opereren.

Van 1996 tot 2015

“Ik begrijp mensen die zeggen dat het hun laatste film is. En een paar jaar later maken ze een nieuwe. We zeggen tegen ze... ‘je zei dat.…’ Ja, dat zei ik. Ik heb niets gezegd. Maar ik dacht het heel hard na Un divan, het was te zwaar geweest... Dit was niet waarom ik films wilde maken na het zien van Pierrot le fou. Toen kwam ik pas echt in de wereld terecht. De wereld van volwassenen die denken dat ze volwassen zijn. Ik had ‘le mineur’ waar Deleuze het over heeft achtergelaten. En ik was in het lawaai terechtgekomen. Ja, met Un divan was ik opgehouden met stil te staan bij dat niets waar mijn moeder het over heeft als ze zegt dat er niets meer te vertellen valt.”

De 1996 à 2015

« Je comprends les gens qui disent que c’est leur dernier film. Puis quelques années plus tard, ils en font un autre. On leur dit... vous aviez dit que… Oui, je l’avais dit. Moi, je n’ai rien dit. Mais je l’ai pensé très fort après Un divan, ça avait été trop dur... Ce n’était pas pour ça que j’avais voulu faire du cinéma après avoir vu Pierrot le fou. Là, j’étais carrément entrée dans le monde. Le monde des adultes qui se prennent pour des adultes. J'avais quitté le mineur dont parle Deleuze. Et j’étais tombée dans le bruit. Oui, avec Le divan, j’avais arrêté de ressasser ce rien dont parle ma mère quand elle dit, il n’y a rien à ajouter. »

From 1996 to 2015

“I understand people who say that this film will be their last. Then, a few years later, they make another. People tell them, but you said... Yes, I said that. As for me, I never said anything. But I’d thought about it hard after Divan, it had been too difficult... That wasn’t why I’d wanted to make films, having been inspired by Pierrot le fou. With that film of mine, I’d truly become an adult. Joined the world of adults who act like adults. I’d left behind the minority that Deleuze speaks of and I’d fallen into the noise. Yes, with Divan, I’d stopped dwelling on the nothing that my mother talks of when she says, there’s nothing to add.”

Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest (2023)

By choosing to efface ideology and fanaticism, The Zone of Interest displays a woefully poor understanding of its subject. Historical analogy, as the great historian Marc Bloch once noted, cannot be reduced to a “hunt for resemblances” or satisfy itself “with forced analogies” but rather has the task of discovering the specificities of different historical periods. It is only through the use of analogy and disanalogy that the historian can, at the same time, seize the past and the characteristic newness of our present.

The Adventurers of ’80s Cinema

These filmmakers were all ciné-adventurers. Which is not the same as conquerors. It was never about claiming others’ space but carving out a new one for themselves. Modestly and self-assuredly, they were each content with mapping the fictions of a single street or two. This way, they managed “to grant a filmic dignity to that which didn’t have any,” as Serge Daney once remarked about the true meaning of realism. They created images where none existed. Therein lie their politics.

A Conversation with Johnnie Burn, Sound Designer of The Zone of Interest

Johnnie Burn is known for his collaborations with Jordan Peele and Yorgos Lathimos, and recently he was awarded an Oscar for Best Sound for his work on The Zone of Interest by Jonathan Glazer. This interview provides an insight into how this collaboration started and how Burn approached the project as a sound designer.

Moed is zichzelf voldoende als gebaar, als spektakel, als vertoning. Het moedige is de mannelijke tegenhanger van de striptease. In Je tu il elle dient dit gebaar niet de bravoure, maar de inzet, de allure, de reikwijdte van een oeuvre en van bekommernissen. Akerman gebruikt zichzelf niet als “bron” van confidenties, maar als markering van een domein, als bezit nemen van haar medium, van haar “ruimte”. En deze ruimte reikt zoveel verder dan die der persoonlijke bekentenissen.

Like the children with whom they share the playmat, the actors indulge in a type of fiction that claims to represent nothing. They invent their characters and narrative lines as they go.

Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975)

Few films have had more written, thought and said about them than Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), made by Chantal Akerman when she was only twenty-four years old. Jeanne Dielman is a must-see film. A “masterpiece,” an absolute milestone in film history. I myself have never seen Jeanne Dielman. Writing out the words almost feels like an admission, a confession. A screening was scheduled for Sunday March 24 at CINEMATEK as part of the big Akerman retrospective. Yet I hesitated until the last moment to actually go see the film.

Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975)

Er zijn weinig films waar meer over geschreven, gedacht en gezegd is geweest dan Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), gemaakt door Chantal Akerman toen ze nog maar 24 jaar oud was. Een “meesterwerk”, een absolute mijlpaal in de filmgeschiedenis. Ikzelf heb Jeanne Dielman nog nooit gezien. De woorden uitschrijven voelt bijna aan als een bekentenis, een biecht. Op zondag 24 maart stond in CINEMATEK een vertoning op de agenda in het kader van de grote Akerman-retrospectieve. Toch twijfelde ik tot op het laatste ogenblik om effectief de film te gaan bekijken.

Interview met Sofie Benoot over Apple Cider Vinegar (2024)

De titel van het nieuwste werk van Sofie Benoot lijkt niets met de film zelf te maken te hebben. Het is alsof de titel wil ontsnappen aan de film, die rondzwerft over heel de wereld en neerstrijkt in Palestina, Noord-Amerika, Engeland en Kaapverdië. Lange tijd dacht Benoot eraan om haar film My Strange Planet te noemen. De film omhelst de aarde, het is een liefdevolle geste aan de materie waaruit onze planeet bestaat: steen. Het is een speelse exploratie van de wereld van steen waarin een fictionele gepensioneerde vertelster die vele natuurdocumentaires van commentaar voorzag de route uitstippelt. Haar stem is de gids op een reis die begint binnen in haar lichaam.

lk zie berichten over snel stervende bossen en noteer met korte verbijstering hoe gewoon we allemaal doorleven, nauwelijks aangeraakt. lk denk aan de nieuwe film van Frans, Windschaduw.

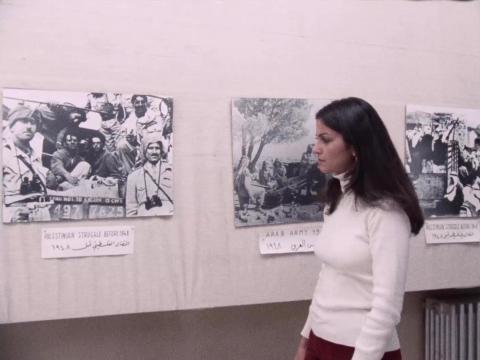

On ne définirait rien en disant que Le fond de l’air est rouge (1977) est un film de montage sur les événements de ces dix dernières années. Rien de ce qui a été fait jusqu’ici ne ressemble à l’entreprise que Chris Marker vient de terminer. Ce qu’il a demandé au montage, ce n’est pas une histoire des événements, c’est sur ces événements une réflexion en images. Dans ce film de quatre heures il a appelé ou rappelé à lui tout ce qui a pu soulever nos espoirs et nos colères, comme pour faire le bilan d’une conscience politique commune à tous ceux qui, d’une manière ou d’une autre, ont cru et croient à la révolution.

Nothing would be defined by saying that Le fond de l’air est rouge (1977) is a montage film about the events of the last ten years. Nothing that has been made until now resembles the undertaking that Chris Marker has just completed. What he asked of the editing was not a history of events but a reflection on these events in images. In this four-hour film, he called up or recalled everything that raised our hopes and anger, as if to take stock of a political consciousness shared by all those who, in one way or another, believed and still believe in the revolution.

Net als de kinderen met wie ze de speelmat delen, beleven de acteurs in Jacques Rivette’s Out 1 een vorm van fictie die niets claimt te representeren. Al spelend verzinnen ze hun personages en narratieve lijnen.

Chris Marker’s Le fond de l’air est rouge (1977)

So, the question Marker leaves us with may in the end be a fairly simple one: Are we the mere survivors of a dead historical sequence of protest, unable to get beyond our fascination with images of lively protest, feeding ourselves with commemorations of events belonging to a safe and distant past? Or, can those “historical grins” or, if you like, grins of history invite us to become their support and bearers, to be their catlike subjects again? Simply put, where are the cats who, as Marker reminds us in Le fond de l’air est rouge, are never to be found on the side of power?

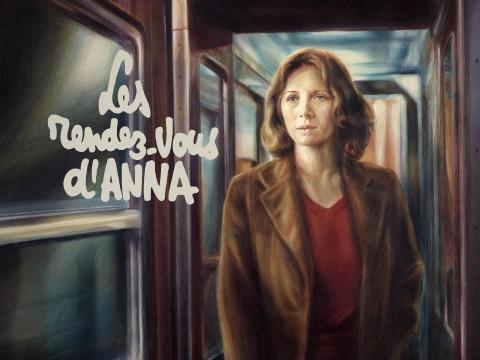

A propos de l’affiche de Les rendez-vous d’Anna

C’est donc déjà tout le génie de cette affiche de n’avoir pas choisie Anna sur un quai de gare, ou pire encore : Anna accompagnée d’un amant d’un soir, d’une mère, ou d’un ex-mari, comme ces horribles affiches actuelles qui mettent artificiellement en scène une chaîne de personnages autour d’un personnage central : Anna n’a pas besoin d’eux pour faire corps. Elle est à face à nous, de tout son poids. Elle est dans le mouvement de sa réflexion, et cette réflexion l’arrête net. Elle est à un tournant de sa vie, du mouvement de sa vie, celui où l’on interroge son désir. Le train transporte ce désir de ville en ville : Essain, Cologne, Louvain, Bruxelles-Midi, Paris Gare du Nord.

Killers of the Flower Moon (Martin Scorsese, 2023)

The entirety of the film – the renowned actors, the worn renditions, the calculated sense of ambition, the stakes of the historical drama, the scenery’s duly monumental look; signed by film grandmaster Scorsese – is bound to evoke the magisterial aura of cinema as a distinguished art form. As a cinematic product, Killers answers to a total image of cinema, with no loose ends and expertly bricked up; nothing is lacking here. Scorsese thereby serves up a cinematic space utterly saturated, with no perspectives or lines of escape, except for the actual corridors through which viewers can leave the theatre.

Killers of the Flower Moon (Martin Scorsese, 2023)

Het geheel van de film – de bekende acteurs, de gedragen vertolkingen, de berekende ambitie, de historische inzet, de monumentale uitstraling; gesigneerd door de filmgrootmeester Scorsese – moet bij het publiek vooral een magistraal beeld van cinema als gedistingeerde kunstvorm oproepen. Als filmisch product beantwoordt Killers aan een totaalbeeld van cinema, zonder losse eindjes en vakkundig dichtgemetseld; er ontbreekt niets aan. Scorsese schotelt ons een volkomen verzadigde filmische ruimte voor, zonder perspectieven of vluchtlijnen, behalve dan de werkelijke corridor naar de uitgang.

Aantekeningen bij Toute une nuit

Het kortstondige opduiken van personages in de nacht – waarvan Akerman stelt dat die “als een grote studio is” – reflecteert de bioscoopervaring van een donkere ruimte waarin op een scherm veranderlijke, vluchtige beelden worden geprojecteerd. De filmvertoning verlicht soms het ene, dan weer het andere deel van het publiek, doet het in het donker van de cinemazaal even oplichten. Daardoor is het alsof de nacht van Toute une nuit, met zijn kunstmatige licht van lantaarns, lusters en autolampen, uit het scherm komt gestroomd, een continuïteit vormt met de donkere ruimte waarin de kijker zich bevindt en, omgekeerd, de kijker een universum binnentrekt waarin personages van vlees en bloed, met een ongetwijfeld even complex als boeiend levensverhaal, herleid worden tot schimmen, tot nauwelijks belichte figuranten in een nachtelijk duister dat vele malen sterker en levendiger is dan degene die het omhult.

Synopsis et personnages

Les morceaux de texte suivants sont issus des archives de la Fondation Chantal Akerman et font partie du matériel de travail d’Akerman pour Golden Eighties (1986). Akerman : « Une comédie où les personnages parleraient vite, se déplaceraient vite et sans cesse, mus par le désir, les regrets, les sentiments et la cupidité ; se croiseraient sans se voir, se verraient sans pouvoir s’atteindre, se perdraient sans que nous les perdions de vue pour se retrouver enfin... »

Synopsis, Characters

The following pieces of text originate from the Chantal Akerman Foundation archives and are part of Akerman’s working material for Golden Eighties. Akerman: “A musical whose characters speak quickly, move quickly and without pause, motivated by desire, regret, passion and greed, who pass each other without seeing, see each other without reaching, or lose each other (we never lose them) only to find each other in the end.”

In the following discussion, which took place in September 2023 in Bucharest during a masterclass that followed a screening of Costa’s latest short film, As Filhas do Fogo [The Daughters of Fire] (2023), Costa sketches an autobiography that is subjective (and thus, slightly incomplete). He discusses his experience of the Carnation Revolution as a teenager and his days as a student of history at the University of Lisbon, where his contract with the geographer and historian Orlando Ribeiro left a deep imprint on him. Describing his films up to his 2006 magnum opus, Juventude em marcha [Colossal Youth] (2006), Costa focused in particular on the revelatory experience of his second feature, Casa de Lava (1994), and the moment of rupture and revelation that was No quarto da vanda [In Vanda’s Room] (2000).

Interview with Ula Stöckl

My work “with” women also concerns the men with whom they live. For who could imagine women without their men? The women's movement is not just the province of women. At a time when women are completely without rights, we need the movement as an absolute necessity. Can men learn from us and begin to see their own misery at the same time that we women attempt to make films about emerging from our misery? If so, then the women's movement will have seen its time.

Interview with Helga Reidemeister

Should women filmmakers continue to develop themselves and work without the political pressure of adapting to male norms, then it may be possible in ten or twenty years to reflect on what has emerged. Up to now, our films have been more or less first tries without the experience and depth of years of work. And a discussion about concepts might be fatal while there are still so many unexplored possibilities, so many experiments which must and will be attempted.

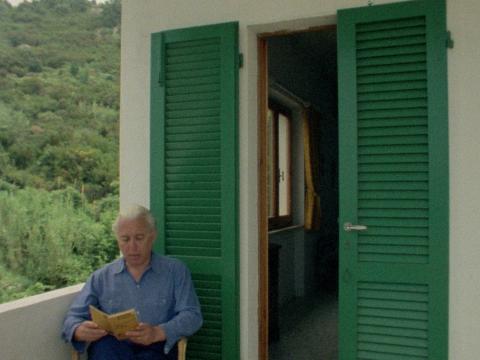

The Cinema of Víctor Erice

Cinema, for Erice, ages at the very moment of its birth, it never stops putting those first sensations at a distance. And there is no remedy for this loss, certainly not the one that would consist in reproducing something, as one places a sheet of tracing paper to reproduce a drawing. From his cinema Erice has banished forever the re-creation, pastiche, the incestuous and vain reference. Instead, he explores dream images, the imaginary, the empire of spectres and sometimes the captivating incarnation of Spirits.

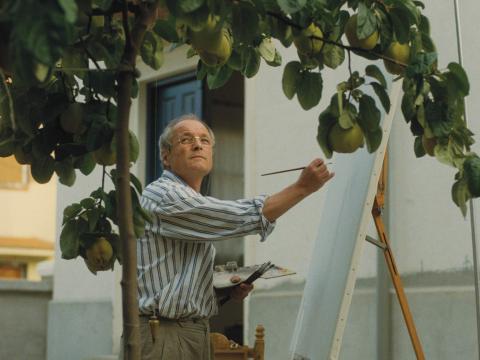

On Víctor Erice’s El sol del membrillo

With its slow rhythm, focus on the mundane and struggle of finishing a single painting, Erice’s El sol del membrillo can be presented as a meditation on the passing of time, hovering between documentary and fiction. Its title, which was translated into English as Dream of Light (The Quince Tree Sun), refers to the sunny period in the autumn that coincides with the ripening of quinces. Both the filmmaker and his painter character attempt to capture the shifting light as it changes with the passing days.

On Chantal Akerman’s Entrance Exam to INSAS

Is it already clear from these short films what type of filmmaker Chantal Akerman would become? Perhaps not. The four films are small exercises, they “tell” us nothing, they’re not really about anything. What the films mainly reveal is a determinate pleasure in filmmaking, in the art of looking, and in the making and organising of images.

Over Chantal Akermans toelatingsexamen aan INSAS

Kan je in deze filmpjes zien wat voor cineaste Chantal Akerman zal worden? Misschien niet. De vier filmpjes zijn kleine vingeroefeningen, ze “vertellen” niets, gaan nergens over. Wat de filmpjes vooral reveleren is een zeker plezier in het filmmaken, in het kijken, en in het maken én organiseren van beelden.

Van 1950 tot 1995

“Ik woonde in Brussel, ik hield helemaal niet van cinema, ik dacht dat het voor idioten was, het enige waar ze me mee naar toe namen was Mickey Mouse of iets in die aard... en toen zag ik Pierrot le fou en ik had de indruk dat het over onze tijd sprak, over wat ik voelde. Daarvoor was het altijd The Guns of Navarone. En ik gaf geen moer om die dingen. Ik weet het niet, maar het was de eerste keer dat ik ontroerd was door een film, en ik was gewelddadig ontroerd. En ongetwijfeld wilde ik hetzelfde doen met films die van mij zouden zijn.”

De 1950 à 1995

« J’étais à Bruxelles, je n’aimais pas du tout le cinéma, je trouvais que c’était pour les débiles, tout ce qu’on m’avait amené voir c’était Mickey Mouse ou des choses comme ça... et puis j’ai vu Pierrot le fou et j’ai eu l’impression que ça parlait de notre époque, de ce que je sentais. Avant c’était toujours Les canons de Navarone. Et je m’en foutais de ces choses-là. Je ne sais pas, mais c’était la première fois que j’étais émue au cinéma, mais alors violemment. Et sans doute, j’ai voulu faire la même chose avec des films qui seraient les miens. »

From 1950 to 1995

“I was in Brussels, I didn’t like cinema at all, I thought it was for idiots, all they took me to see was Mickey Mouse or things like that... and then I saw Pierrot le fou and I had the impression that it spoke of our times, of what I felt. Before, it was always The Guns of Navarone. And I didn’t give a damn about those things. I don’t know, but it was the first time I had been moved by a film, and I was moved violently. And no doubt I wanted to do the same thing with films that would be mine.”

Steeds opnieuw wordt het voortbestaan van Dielman kort in twijfel getrokken. Het publiek blijft even hangen bij de volstrekte onverschilligheid van de dingen en verkeert daarbij in de onzekerheid of Dielman is aangekomen in de andere kamer of in de deuropening is opgelost. De werking is dezelfde als die van het spanningsspelletje waaraan jonge kinderen soms worden onderworpen, waarbij ouders zich verstoppen achter hun handen, en met een kiekeboe weer tevoorschijn komen. Doordat er steeds dezelfde opeenvolging van beelden is van Dielman die de kamer verlaat en de leegte die opkomt, wordt de indruk gewekt van een soort achtervolgingsscène. De leegte zit haar op de hielen en zoekt het juiste moment om haar in te halen.

De personages en thema’s in hedendaagse soaps lijken relatable, maar voor wie? Hoewel divers op het vlak van kleur en seksuele geaardheid, behoren alle personages tot dezelfde middenklasse. Thuis is in die zin meer op Dertigers gaan lijken. Bij de aanvang van de serie vond het drama nog plaats tegen een achtergrond van een sociaal spanningsveld. De personages representeerden verschillende sociaaleconomische posities die dialectisch tegenover elkaar werden geplaatst. Nu wordt één cultuur als de legitieme naar voren geschoven en worden maatschappelijke antagonismen genegeerd.

Durant cette première période, il veut être le physicien de la photogénie, durant la seconde, il en devient le chimiste. Pour ces expériences, le réalisateur est libre d’ignorer les exigences du grand public. Les films deviennent d’ailleurs de plus en plus inaccessibles à la foule, et d’autant plus accessible et jouissif seulement pour un petit cercle d’initiés. Mais une fois que ces essais lui ont permis d’acquérir une connaissance approfondie de la technologie, le cinéaste revient spontanément à la nature, à l’homme. Il revient à la rue. Non pas la rue du studio, la rue en carton, dans les studios, mais la vraie rue le fascine, là où la vie grouille sous mille formes, où elle peut être captée et filmée directement.

During that first period, he wanted to be the physicist of the photogénie, during the second he became its chemist. For these experiments, the director was free to ignore the general public. Film also became more and more inaccessible to the crowd, understandable and enjoyable only to a small circle of insiders. However, once those trials had given him a thorough knowledge of technique, the director naturally returned to nature, to man. He returned to the street. It wasn’t the street of the studio that fascinated him, the street of cardboard, but the real street where life teems in a thousand forms, where it can be caught and filmed directly.

The parentheses in my title arise from the fact that Charles Dekeukeleire, a largely forgotten Belgian experiment filmmaker of the late 1920s, had only small recognition in his own day. Hans Scheugl and Ernst Schmidt, Jr., ... say of his films: “They were so advanced in their formal means, so far ahead of their time, that they left behind the puzzled contemporary critics.” There were in fact a few contemporary Belgian writers who discussed Dekeukeleire’s films with insight, but certainly this minority response was not enough to insure his work a place in cinema history after he turned to documentary filmmaking in the 1930s.

Histoire de détective by Charles Dekeukeleire

The registering apparatus itself becomes a living organ, moving and reacting psychologically. For the spectacle of a world which hitherto was nothing but an animated photograph, dependent for its interest upon form and the movement of figures, is substituted the impression received by the cameraman himself: the result being achieved by the synthesis of two distinct movements, the one that of his own interior life and the other that of external life, modified, designed, transformed in the direction of his psychic impression of it.

Histoire de détective de Charles Dekeukeleire

L’appareil enregistreur devient lui-même vivant, il se déplace et réagit psychologiquement. À la vision du monde qui autrefois n’était qu’une photographie animée, dont la qualité et l’intérêt dépendaient presque exclusivement de la plastique et du jeu des acteurs, se substitue l’impression ressentie par l’opérateur seul, celle qui résulte de la synthèse de deux mouvements distincts, d’une part celui de la vie intérieure de l’auteur, d’autre part, celui de l’extérieur modifié, épuré, transformé dans le sens de l’impression psychique du réalisateur.

It’s up to Arab women, and especially Palestinian women, to take up the camera to show their true face, provided they haven’t adopted a system of values created by men (as happened a number of times with their European counterparts). They alone, without a doubt, can show that Palestinian women today resist as women always have in history, as citizens of a country wiped off the map and one half of a people who refuse to die, but also as all women of the world who suffer a double oppression.

“Van het begin af heb ik geweten dat ik wat wij noemen ‘zuivere films’ zou maken, films zonder verhaal en die belangwekkend zijn door de beweging alleen: een beweging die er niet noodzakelijkerwijs een behoeft te zijn van personages. Alles is goed om er beweging mee te bereiken: men kan de beweging fotograferen in de natuur, men kan bewegingsloze dingen laten dansen en draaien door middel van het toestel; men heeft de beweging der machines, enz. Het is verkeerd te spreken van trucs, in de filmtechniek. Wij kennen geen trucs, wij hebben alleen maar middelen.”

Eduardo Williams on The Human Surge 3 (2023)

In the playful “sequel” to his 2017 festival breakthrough, The Human Surge, Williams tackles the erratic mechanisms of virtual-reality technology through the lucid hyper-reality of a group of characters ranging from different latitudes in the so-called Global South. Captured entirely with a 360-degree lens that’s normally reserved for VR but projected on a traditional cinema screen, the film follows three groups of friends from Taiwan, Peru and Sri Lanka who meet, converse and traverse through space and time as the film helps transport them across borders through the magic of cinema.

Ridley Scott’s Napoleon

Scott’s late-career method is to mix different modes: the epic and the banal, the serious and the ridiculous, the lyrically beautiful and the brutally violent. In Napoleon, the past is strange not because of its odd customs, but because we – from the detachment of our contemporary vantage point – can see all these different modes at work, simultaneously. The result is often comical, but also harrowing: history as some kind of terrible joke.

Een gesprek met Bas Devos over Here (2023)

Naar aanleiding van de Belgische release van Here sprak Sabzian met Bas Devos over het maakproces van zijn vierde langspeelfilm: “Van de weeromstuit worden dingen die onze aandacht vragen plots groter. In dat opzicht is cinema iets archaïsch eigenlijk. Veel films worden gemaakt met de verwachting dat het publiek tegelijk ook wel op Instagram zal zitten. Die films maken net genoeg lawaai op belangrijke momenten zodat je de Marvel-held ergens tegen ziet vliegen. Maar er is ook een ander soort cinema dat standvastig probeert te zeggen: hier gebeurt iets, nu. Ik vind het heel leuk dat zoiets kan in een cinemazaal.”

One of the most important, but also often overlooked, dimensions in the work of Trinh T. Minh-ha, is musicality. A musicality that can be felt in all facets of her work, expressed as exquisite configurations of breath, rhythm, silence, and timbre. As we hear her saying in her latest film, What About China? (2022): “reality is musical.” In 2023, Trinh T. Minh-ha was invited as an artist in focus for the Courtisane Festival. Head programmer Stoffel Debuysere talked with her about the music, the musical thinking and the thinking in musical terms that is at the heart of her work.

Que des rencontrent produisent de l’art, ce n’est pas exceptionnel ; ce qui l’est, c’est qu’une loi morale soit extraite de ce hasard : la contingence engendre un impératif éthique auquel l’artiste ne peut se soustraire, « parce que l'arbre, c'était aussi Antigone. » Straub et Huillet ont pris au sérieux cet impératif qui peut paraître absurde (pourquoi ne pas planter soi-même un arbre, là où c’est nécessaire ?) mais qui est, en même temps, parfaitement logique : si le personnage principal (pas l’acteur !) meurt avant le tournage, alors le film ne peut être réalisé.

That encounters bring forth art is not exceptional, but a moral law being extracted from chance is: contingency brings forth an ethical imperative from which the artist cannot escape, “because this tree was also Antigone”. Straub and Huillet took this imperative seriously, an imperative that may seem absurd (why not plant a tree yourself wherever necessary?) but is at the same time perfectly logical: if the main character (not the actor!) dies before the filming starts, then the film can no longer be realised.

Dat ontmoetingen kunst voortbrengen is niet uitzonderlijk, wel dat een morele wet aan dat toeval wordt onttrokken: contingentie brengt een ethische imperatief voort waaraan de kunstenaar niet kan ontsnappen, “want de boom, dat was ook Antigone”. Straub en Huillet namen deze imperatief serieus, een imperatief die absurd mag lijken (waarom niet zelf een boom planten waar nodig?) maar tezelfdertijd volkomen logisch is: als het hoofdpersonage (niet de acteur!) sterft voor de opnames dan laat de film zich niet meer verwerkelijken.

In its sudden and raw appearance in 2011, Schakale und Araber felt both a “weapon of criticism” (of humanity) and a “criticism of the weapon” (video). Straub deliberately shot against the light. The sun is not sweet here but burning, the air not full but suffocating. White phosphorus, video voltage. For maybe the first time in Huillet/Straub the hoarseness of the medium passed into the material, even if to serve the subject.

One could hold against me that the following has only a very remote connection with the individual films shown in Knokke and that it is a postulate rather than a description of reality. Well, that is how it is intended, not as some far-fetched defence of everything that was shown in Knokke. I would not be able to judge these films in any meaningful way: a regular moviegoer so rarely comes into contact with this genre that its strangeness alone is initially confusing.

Le Cinéma qui m’a toujours le plus intéressé, celui qui me nourrit, c’est un cinéma qui prend parfois son temps, il se fait attendre, c’est celui qui, généralement, se fabrique dans l’ombre, à la marge, dans les périphéries du monde ; C’est un cinéma que l’on découvrira peut-être dans 10, 20 voire 30 ans et qui dira probablement mieux notre époque que ce que nous étions alors capable de voir.

The cinema that has always interested me the most and which nourishes me is a cinema which takes its time and makes you wait. It’s one that is generally created in the shadows, on the margins, on the world’s periphery; it’s a cinema that we will perhaps discover in 10, 20 or even 30 years and which will probably capture our era better than anything we were able to glimpse at the time.

De cinema die me altijd het meest heeft geïnteresseerd en die me voedt, is cinema die soms rustig de tijd neemt en op zich laat wachten. Het is film die doorgaans in de schaduw wordt gemaakt, in de marge, in de randgebieden van de wereld; film die misschien over tien, twintig, ja dertig jaar zal worden ontdekt en die waarschijnlijk een juister beeld van onze tijd zal geven dan wat we zelf konden zien.

An Interview with Tewfik Saleh

My duty as a filmmaker consists in furnishing the arms of critique, the intellectual means to understand what happens so that the spectators are not “had” by what they’re told. I don’t believe at all that The Dupes is a negative film because it talks of failure. My position is a little like the mother who warns her child, “If you do this, this is what will happen. If you go into the woods, you will be eaten by the wolf…”

Een gesprek over WTC A Love Story (2020) en WTC A Never-ending Love Story (2023)

Sinds 2017 nemen Lietje Bauwens en Wouter De Raeve de stedelijke vernieuwing in de Brusselse Noordwijk onder de loep. Dit onderzoek resulteerde in de films WTC A Love Story (2020) en het recente vervolg, WTC A Never-ending Love Story (2023), dat ze samen regisseerden met Daan Milius. Dagmar Teurelincx en Timeau De Keyser gaan in gesprek met Lietje Bauwens, Wouter De Raeve en hun filmdramaturg Daan Milius, over het gebruik van spel en fictie in hun films.

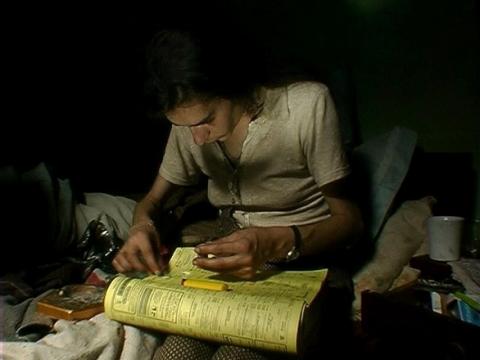

A Conversation with Pedro Costa on In Vanda’s Room

Cyril Neyrat: What is the origin of In Vanda’s Room?

Pedro Costa: Considering the film as it is now, the form it has, it can only come from things like tiredness and disgust. Not from a search. Nor from a rupture, in the sense of a film that you make by saying to yourself: “I’ve got an idea, I’m going to make a film with this form, in this environment.” It surely comes from the years before cinema, from something other than cinema. It doesn’t come from childhood but surely from adolescence, in other words from the bedroom.

It will take me a bit longer to love Vanda, but how can I say “no” to someone who says “yes” to everyone, to someone with the most beautiful shots in the film and, always or nearly always, with the list of yellow pages on her lap, as dazzling as the light from “chasing the dragon” in the dark or the silver lying about in every drawer, so luminously punctuating the film?

Il Cinema Ritrovato 2023

Drie bezoekers van Il Cinema Ritrovato bespreken drie films die ze dit jaar op het festival zagen en die hen bijbleven.

Il Cinema Ritrovato 2023

Three Il Cinema Ritrovato visitors discuss three films that they saw at this year’s festival and which stayed in their memories.

On Justine Triet’s Anatomie d’une chute (2023)

In strict accounting terms, Triet’s project has an undeniable plausibility – all the elements of the grand film draw present and Anatomie is hardly shy about its quality labels. Despite its critical theory and templates, however, Triet’s film all too often falls victim to its director’s quest for recognisability: a gentrified family film cannot so easily transcend the bounds of its genre.

Over Anatomie d’une chute (2023) van Justine Triet

Puur boekhoudkundig lijkt Triets film nochtans foutloos; alle elementen van de grand film tekenen present en Anatomie wil zijn kwaliteitslabels niet wegsteken. Ondanks de kritische theorie en handige sjablonen wordt Triet vooral het slachtoffer van haar eigen zoektocht naar herkenbaarheid: een gegentrificeerde televisiefilm overschrijdt niet gemakkelijk de grenzen van zijn genre.

A Conversation with Heinz Emigholz

The film is not ready in my head before we shoot it. The sculpture in time we produce is evolving during a passage of work. That’s why I like the actual filming; your mind has to be 100 percent present. Yes, I know what’s coming next because I don’t film tableaus that have no connection to the neighbouring images. I’m filming and editing a network in which one image leads to another, in which an image remembers the one before and anticipates the one following. It’s a little bit like playing chess.

Beelden uit films worden in onze geest voortdurend gedistilleerd en raken vervlochten met herinneringen uit ons eigen leven, waardoor aanhoudend nieuwe verhalen ontstaan. Het is niet zozeer het eigenlijke kijken naar films maar wel de beelden uit films die daarna in ons geheugen blijven hangen die cinema het rijk der dromen in duwt. In ons geheugen krijgen beelden een grenzeloos potentieel.

Les images des films sont constamment distillées dans notre esprit, où elles se mêlent aux souvenirs de nos propres vies, générant perpétuellement de nouvelles narrations. Ce n’est pas tant l’acte de regarder des films que les images des films qui persistent dans notre mémoire et poussent le cinéma dans le domaine des rêves. Dans nos souvenirs, les images deviennent porteuses de possibilités infinies.

Images from films are constantly being distilled in our mind, where they intertwine with memories from our own lives, perpetually generating new narratives. It’s not so much the act of watching films as it is the images from films that linger in our memory thereafter that pushes cinema into the realm of dreams. In our memories, images, become pregnant with infinite possibility.

A Conversation with Antoinetta Angelidi and Rea Walldén

The kind of cinema I’m trying to do is a composition of traces, from the history of culture as collective memory, but mainly as collective unconscious. We have traces of the history of art and then personal experiences. These are the raw materials. I distance myself from reality in order to come closer to the Real, with a capital R. The Real is non representable.

Truffaut still has a clear preference for frustrated, failing heroes, for feelings stranded along the way. But the extremes of pathos and self-irony, of lyricism and banality, have come ever closer together, so that Truffaut’s theme has simply become that of unhappy love, where pity can more and more take root.

Nog steeds heeft Truffaut een duidelijke voorkeur voor gefrustreerde, mislukkende helden, voor gevoelens die onderweg stranden. Maar de extremen van pathos en zelfironie, van lyriek en banaliteit zijn steeds dichter bij elkaar komen liggen, zodat Truffauts thema banaalweg dat is geworden van de ongelukkige liefde, waarbij het medelijden steeds meer wortel kan schieten.

Chabrol bothers. He bothers me too, I must admit. He frustrates my universally recognised, unchallenged right as an art consumer to know where the maker stands, where he wants me to be and what he has to say to me. I prefer a banal message to an undecipherable one. I prefer a banal vision to a constantly changing one. I prefer a hypocritical morality to a morality of hypocrisy.

Chabrol stoort. Mij ook, moet ik toegeven. Hij frustreert mij in mijn universeel erkende, door niemand betwiste recht als kunstconsument om te weten waar de maker staat, waar hij me wil hebben en wat hij me te zeggen heeft. Liever een banale boodschap dan een niet te ontcijferen boodschap. Liever een banale visie dan een voortdurend wisselende. Liever een hypocriete moraal, dan een moraal van de hypocrisie.

The Lovers on the Bridge (1991)

Besides the macabre, there is luxury: the hyper-production, the mannered image, the baroque fairylike. Carax does try to fit the two together – clinical decay and magical image construction, macabre corruption and pièces montées [layer cakes] of light and fireworks – but it doesn’t really work. The suture doesn’t happen. Two different films chase each other, trip over one another, tear each other apart like two dogs on the same leash.

Les amants du Pont-Neuf (1991)

Naast het macabere is er de luxe: de hyper-enscenering, het gekunstelde beeld, het barok-feërieke. Carax probeert beide wel in elkaar te schuiven – de klinische aftakeling en de magische beeldopbouw, de macabere corruptie en de pièces montées van het licht- en vuurwerk – maar het wil niet echt lukken. De hechting komt er niet. Twee verschillende films hollen achter elkaar aan, struikelen over elkaar, verscheuren elkaar als twee honden aan dezelfde leiband.

Indeed, what is called new music today has become decontextualized from tradition and history, endlessly grasping at fashionable trends, and is ultimately marching off a cliff. “Once you’ve hammered into people the idea that only what is contemporary and modern exists, be it economic fashions or the supposed political or moral coercions, then it gets to the point where the human being believes he lives better than anyone has ever lived before or ever could live. No movement occurs anymore.” For Huillet and Straub, Von heute auf morgen is “a declaration of war” against modernization to reaffirm the possibility for something truly new, indeed a new music of which Schoenberg would have been proud.

Where, during this “visit to the Louvre,” fifteen years after Cézanne (1989), is the painter whom Gilles Deleuze called “the Straubs’ master”? He is neither in the museum nor the series of paintings that make up this particular visit. Yet he occupies a central place through the text that a voice-over reads aloud; a material that could not be more impure, composed of memories, perforated with borrowed quotations, invented expressions, and passages of pure fiction in indirect style.

It would be foolish to call this picture minimalist, for even if its rich sound (a baby cries on the line “…the collective hate” in version A) were turned off, one could be fascinated by the violent changes of color in wardrobe and sunlight, here effected by jump cuts – yet another cinematographic vein Straub has tapped for both sudden and gradual excitation. Fascination, magic, and belief are part of Huillet/Straub’s cinema, too, occurring amid their total opposite – analysis, critical faculty, errant thought – and back again. One may feel upon leaving the theater a sharpening of the senses.

Gilles Deleuze remarked that your image is a “stone” and your take is a “tomb”. The earth is abandoned and yet, as it were, it is filled with generations of corpses. When, for example, towards the end of Operai, contadini, you make a long sweeping pan across the hillside, the physical space comes across as being strangely humanised in the light of what was said beforehand. The hillside seems to be populated by people. Hence history becomes the humanization of nature. What is “human” in this panning shot, and what is “nature”?

Jean-Marie Straub, a fighter of images and sounds, chose a paragraph corresponding to the beginning of Bernanos’ pamphlet. He did not change a word. He used two versions of the same shot, each with full credits. At the start of the first version, twilight, a swan accompanies actor Christophe Clavert as he walks along the lake reciting Bernanos’ text, and then it disappears. At the end of the second version, brighter, a swan appears, passes the motionless actor, and drifts off to the left. The swans are among us, Nature will prevail, and the film offers this final gesture of unprecedented optimism – perhaps so that we can carry on, that is to say, fight, just a little longer.

Shots like this may not commonly be considered as examples of the plan straubien, but the numbers shown on screen possess the same incontestable reality to them, the same évidence. Like the monuments, streets and fields elsewhere in the film, they are there. Behind these figures – as much as the Zionist movement may try to deny it, and as much as anybody expressing solidarity with the Palestinian cause may be harassed, politically ostracised and baselessly slandered as antisemitic – lies the trauma suffered by an entire people.

A Conversation with Jean-Charles Fitoussi

From the time you are born, your eyes are open, and you see everything for the first time. The older you get, the less you are surprised by things. But things have not changed, it is just you who have changed, things can still be very surprising. It is such a pity that we are losing the perception of how surprising things are. I believe that in Huillet and Straub’s films, you are given back the feeling of a surprising world. To see the things that are in front of you becomes completely incredible.

All we can do is try to do our job as well as we can – but that too is so stupid, to have to fight for a film not to be ruined, considering how many other (more important?) things – people – we ought to be fighting for. And yet you must fight for a film “pour ne pas céder”. Godard claims that you don’t last long on your own, but maybe that’s all you can do: hold out as long as you can…

Interview with Mattéo Eustachon, One of the Directors of Mourir à Ibiza

When you’re working on a film, there are a lot of things over which you have no control, especially when there’s no precise script. When you look at the rushes, you see the film in a whole new way. You get the feeling that it’s been built piece by piece. If there was a bad atmosphere on the set, you could feel it in the film. There’s something that comes from the experience of making the film. That’s the magic of filmmaking. What drives us to make films for the rest of our lives is the constant desire to do things differently, to do things better, to experiment. I can’t wait to see the next film we make.

Entretien avec Mattéo Eustachon, l’un des réalisateurs de Mourir à Ibiza

Pendant que l’on travaille sur le film, il y a beaucoup de choses sur lesquelles on n’a aucun contrôle, d’autant plus quand il n’y a pas de scénario précis. Lorsqu’on regarde les rush, on voit le film d’une toute nouvelle manière. On a le sentiment qu’il a été construit pièce par pièce. S’il y avait une mauvaise ambiance sur le plateau, cela se ressent dans le film. Il y a quelque chose qui vient de l’expérience du tournage. C’est la magie du cinéma. Ce qui nous pousse à faire des films pour le reste de notre vie, c’est le désir constant de faire différemment, de faire mieux, d’expérimenter. J’ai hâte de voir le prochain film que nous ferons.

After Winter Comes Spring – Presaging the Wende

Over and above the almost sensational signal it sent at the time, Winter Adé continues to be an artistically important and aesthetically coherent film, in which the interaction between directing, cinematography and editing yields a composition that one could almost call choreographic. But above all it is the accuracy and tenderness of its observations that make the film stand out in late DEFA film history. As a result of Misselwitz’s personal style, her gentle interviews and her empathy for the women she meets, her film achieves those qualities that still impress us today.

Jungle Fever is a strange, grandiose and disappointing American film! Once again, it shows how America’s powerful, coercive story-industry deals exclusively in stereotypes. Making diversity visible and recognisable has always been its essential function and source of inexhaustibility. In the film, we do see the symptoms, the signals of diversity, but not the difference.

Jungle Fever is een vreemde, grandioze en teleurstellende Amerikaanse film! Eens te meer blijkt hoe Amerika’s machtige, dwingende verhaalindustrie uitsluitend in stereotypen handelt. Het zichtbaar en herkenbaar maken van de diversiteit is steeds haar essentiële functie en de bron van haar onuitputtelijkheid geweest. In de film zien we dus wel de symptomen, de signalen van de diversiteit, maar niet het verschil.

A Tale of Winter by Éric Rohmer

A Tale of Winter is a very intelligent, very moving film. The images were made from the endless distance of the other side of the universe; they do not carry the characters but look for them, reach for them without being able to give them anything back. The poor attention of those images alone is enough for the spectator! The director does not wrap his story but leaves it vulnerable on the table among crumpled newsprint.

Conte d’hiver van Eric Rohmer

Conte d’hiver is een heel intelligente, heel ontroerende film. De beelden zijn vanuit eindeloze verten aan de andere kant van het universum gemaakt; ze dragen de personages niet maar zoeken ze, reiken naar hen zonder ze iets van zichzelf te kunnen geven. De armoedige aandacht van die beelden alleen al is voor de toeschouwer voldoende! De regisseur pakt zijn verhaal niet in, maar laat het kwetsbaar tussen verfrommeld krantenpapier op tafel liggen.

A New Life by Olivier Assayas

Acting happens in the shot, not between the shots. Assayas edits as little as possible and does not construct the acting effect from beautiful fragmentary acting details edited together as fluidly as possible. No, he observes the acting in its unmanipulated continuity. This has profound implications for the construction of the film.

Une nouvelle vie van Olivier Assayas

Acteren gebeurt in het plan, niet tussen de plans. Assayas monteert zo weinig mogelijk, bouwt een spel-effect niet op uit mooie fragmentarische speldetails, die zo vloeiend mogelijk aan elkaar zijn gesneden. Nee, hij observeert het spel in zijn ongetrukeerde continuïteit. Dat heeft ingrijpende gevolgen voor de bouw van de film.

Lorsque j’ai lu le texte du critique Manny Faber sur un film expérimental indispensable, j’ai remarqué qu’il y avait quelque chose d’extraordinaire. Une façon d’adjectiver ce qui semblait insaisissable après l’avoir vu. Il ne s’agissait pas seulement de traduire une expérience, mais de trouver le matériau exact qui transmettrait ce qui se réverbère sur l’écran.

Toen ik de tekst van criticus Manny Faber las over een cruciale experimentele film, merkte ik iets bijzonders op: een manier om te adjectiveren wat onbegrijpelijk leek nadat je het gezien had. Het was niet alleen een kwestie van het vertalen van een ervaring, maar ook van het vinden van het juiste materiaal om over te brengen wat er op het scherm zindert.

Cuando leí el texto del crítico Manny Farber sobre un film experimental indispensable noté que había algo extraordinario. Un modo de adjetivar aquello que parecía inasible tras haber sido visto. No solo se trataba de traducir una experiencia, sino de encontrar la materia exacta que transmitiera aquello que reverbera en la pantalla.