The Night of Counting The Years

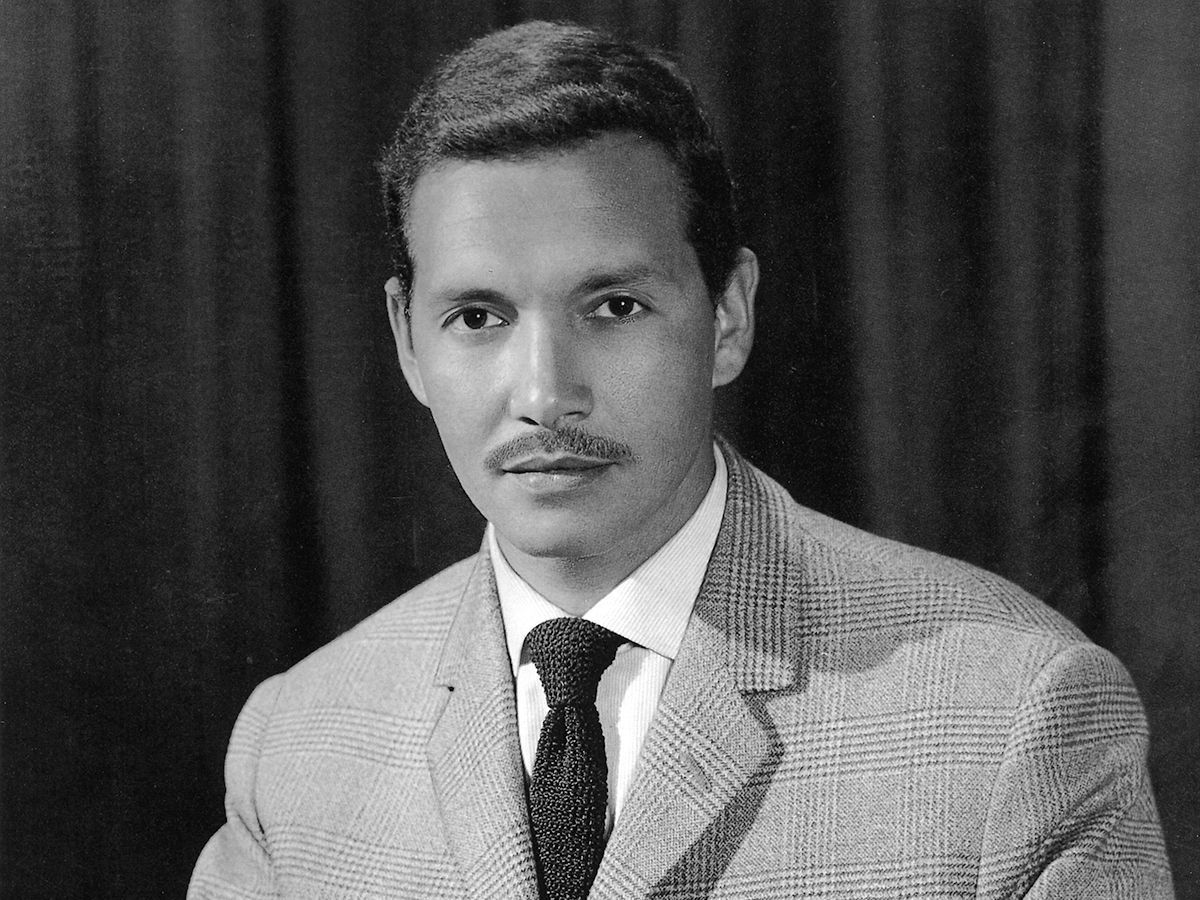

The Mummy by Shadi Abdel Salam

Shadi Abdel Salam’s Words

A Screenplay by Shadi Abdel Salam

From the very beginning, I have had a cause.

My cause is our lost or missing history.

The people you see on the streets, in the fields, factories and even those at home… they all contributed once to forming, to creating life.

Those people have enriched human civilization.

How can we revive their creative role?

How can we restore their positive and constructive participation in life and human endeavour?

First, they have to know where they come from and what contribution they made.

We must form a link between the past and the present Egyptian, in order to attain the Egyptian of tomorrow.

This is my cause.

“You who go, you will return / You who sleep, you will rise / You who walk, you will be resurrected.” So begins Al-mummia or The Night of Counting the Years, Shadi Abdel Salam’s first and only feature film. The quote derives from the Egyptian Book of the Dead, and it is not only indicative of the events depicted in the film but also of the lifelong desire that infused Shadi Abdel Salam’s work: to rekindle memory in view of activating the future.

After graduating from Victoria College in Alexandria and a short stint studying theatre arts in London, Abdel Salam studied architecture under Hassan Fathy, a man renowned for his promotion of pre-industrial design methods and materials. The crux of Fathy’s argument was a desire to return to the use of ancient mud brick forms, which he described as the “sole hope for rural reconstruction.” This concern for the duality of tradition and modernism, as well as of urban and rural life, undoubtedly influenced Abdel Salam in his forthcoming creative endeavours. Instead of pursuing a career in architecture, however, he opted for cinema, initially shaping his vision by designing decorations and costumes for numerous historical Egyptian films among which Wa Islamah [Sword of Islam] (Enrico Bomba & Andrew Marton, 1961), Almaz we ‘Abdou el Hamoulî [Almaz and Abdul Hamuli] (Helmy Rafla, 1962) and Al Nasser Salah Ad-Din [Saladin] (Youssef Chahine, 1963), as well as foreign films such as Cleopatra (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1963), Faraon [Pharaoh] (Jerzy Kawalerowicz, 1966) and La lotta dell’uomo per la sua sopravvivenza [Man’s Struggle for Survival] (Renzo & Roberto Rossellini, 1964–1970).

It was notably Roberto Rossellini who proved to be instrumental in the procurement of the necessary funding for Al-mummia, a project that had occupied Abdel Salam ever since 1956, when he first read the story of the discovery of mummies in Dayr al-Bahri. Finding inspiration in a historical event that took place in 1881, on the eve of British colonial rule, when it was brought to light that a tribe had been secretly raiding the tombs of the Pharaohs in Thebes, the first-time filmmaker rigorously crafted a haunting meditation on identity, loss and legacy; its deeply melancholic tone tentatively reflecting the sense of demise felt at the time of shooting, in the months following the political cataclysms of 1967, as well as the passing of the filmmaker’s father. When completed, Rossellini ensured that the film received a substantial international audience at festivals throughout Europe in 1970, winning, amongst others, the Georges Sadoul Prize of the French Cinémathèque and the Golden Prize of the Carthage Cinema Festival in Tunis. However, the film was not to receive a release in Egypt until February 1975 — an event that was sadly eclipsed by the death of the renowned Egyptian contralto Umm Kulthum, which plunged the whole country into mourning. Death, it seems, kept on haunting the film.

Abdel Salam continued to delve into Egypt’s history and culture with subsequent cinematic projects, perhaps most notably the short film Shakawa Al-Fellah Al-Faseeh or The Eloquent Peasant (1970), based on a Middle Kingdom text of the same title, in which a peasant, wronged by a greedy nobleman, must rely on his elegant speaking style in order to attain justice. However, while responsible for a number of other short and documentary films after 1970, and being appointed as Director of the Centre for Documentary Films, the great sweep of Abdel Salam’s cinematic work began to take a single direction: preparations for his magnum opus, a film variously referred to as The Tragedy of the Great Royal House and as Akhenaton, which would have dealt “with the dynasty which preceded him [the Pharaoh Akhenaten] and that which followed him.” In spite of fifteen years of intensive preparation and research, during which he not only wrote the screenplay but also diligently designed the costumes, decors and decorations for the film, Abdel Salam was never able to see his dream project come to fruition. He passed away in October 1986, leaving us with a legacy that continues to brim with life and promise.

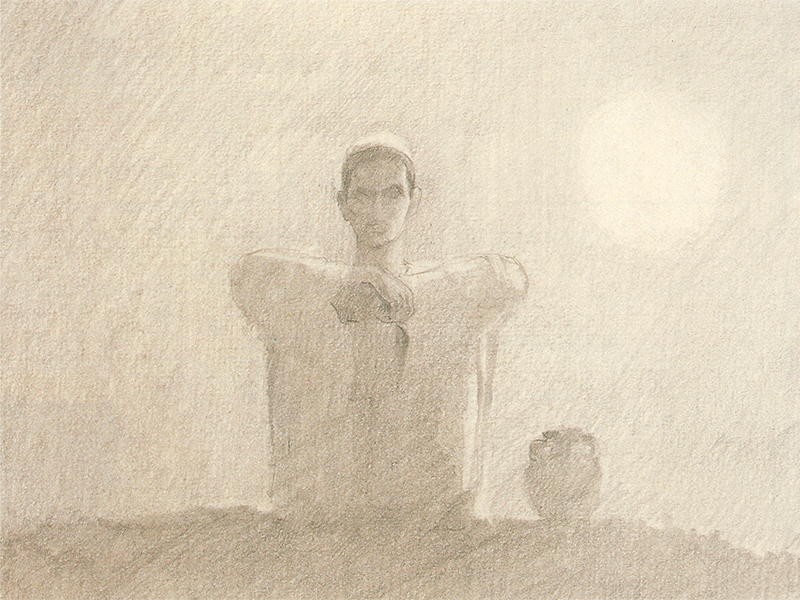

Compiled on the occasion of the online screening of Al-mummia, hosted by Sabzian and Courtisane on 21 January 2021, this small dossier consists of a selection of conversations with and writings on Shadi Abdel Salam, as well as the complete screenplay of Al-mummia and some of the drawings that he sketched in preparation for the film.

Stoffel Debuysere (Courtisane) and Gerard-Jan Claes (Sabzian)