Report from Bologna

About Il Cinema Ritrovato 2022

Film festivals are usually “consequential”: through its selection, a festival makes a statement, speaks out on which films matter and which don’t, which developments within contemporary cinema deserve attention. Via its selection, a festival aims to give a verdict on the current state of cinema, on which course is in keeping with the times. This applies first and foremost to large festivals. There’s no other festival, for instance, that rouses the emotions more than Cannes. The selections are meticulously analysed and discussed, the award-winning films celebrated or criticised, the importance of the festival affirmed or denied time and again. Many smaller festivals operate in the shadows of those A-list festivals, shifting emphasis, taking more risks in their programming, and opting for a “serious geology” rather than a “flashy geography” (Bazin). In doing so, they give meaning to other films as well, providing them with the life, depth and visibility they are denied elsewhere. Festivals are – often reluctantly – lighthouses of contemporary cinephilia, differently arrayed junctions where the artistic value of a film seems to be decided.

When visiting the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna, this search for meaning also looms large: which vision lies behind the programming? What does the selection tell us about cinephilia today? Which cycles and programmes does the festival boast this year and why? It is immediately apparent that this knee-jerk reaction needs to be suppressed, partially at least. Ritrovato is devoted to the rediscovery of “old” films; here, film history is scrutinised in its entirety. The festival presents both restored and “recovered” films, both classics and lesser-known or obscure films, both silent films and “talkies”. Over the years, Ritrovato has built a reputation as the premier festival for film restorations.

And yet there is something about the success of Ritrovato and the state of contemporary cinephilia. For even though the festival only presents restored or recovered films, its retrospective aspect proves to be topical. It displays a film-historical sensibility that is no longer mainstream. This it has in common with other festivals: showing films that would otherwise be difficult or impossible to see, at least not under those (technical) conditions. This festival, too, relies on the notion of the event-related exception. That is precisely its appeal. The festival is simultaneously about loss (something is gone forever, the festival looks back) and triumph (the richness and love of an art in all its forms). It turns Ritrovato into a slightly contradictory experience. Film culture and cinephilia are having a hard time: film magazines are calling it a day, theatres remain rather empty, distributors are taking less risks or going out of business, more and more festivals are struggling with their identity and the impact of streaming platforms. There is little sign of this kind of negativity in Bologna. The festival continues to grow every year, and two coronavirus editions haven’t changed that. The festival’s appeal is pretty simple: watching a film with a large group of film lovers in incredible circumstances, both technically (new restorations, incredible 35mm copies, excellent projections and film theatres) and contextually (introductions, master classes and talks, but also Bologna as a backdrop, quite literally when it concerns the evening open-air screenings in Piazza Maggiore). There is no sign of fetishisation, however. The danger of nostalgia is never looming, no blind idolisation of cinephile rituals or peripheral phenomena. Perhaps this is what makes the festival so unique: the frenetic search for meaning so typical of the festival circuit, shirking real risks in programming, is largely avoided here. Is that just because of the “old” films? Not quite. Strange as it may sound, Il Cinema Ritrovato is a festival where films are not only programmed but also actually watched.

With the 2022 edition, the festival celebrated its 36th anniversary. Fears that the audience would stay away after the coronavirus editions proved unfounded. Some masks and hand-sanitizer popped up here and there, but there were no longer mandatory empty chairs between visitors. Outside, the temperature rarely dropped below 30°C, and even at full blast the air conditioning could barely keep the temperature inside bearable. Spontaneously hopping from one room to another is no longer an option. The reservation system and the queues make it necessary to think ahead. The fact that the city is increasingly bursting at the seams with every edition did not escape the festival organisers. What’s more, the audience is not only bigger but also more diverse, according to curators Mariann Lewinsky and Karl Wratschko in their introduction to the catalogue. Whereas only seasoned and slightly older aficionados used to come to Bologna, the festival now attracts young and more casual film lovers. And that is reflected in the programme, which contained an exceptionally large number of classics this year. With films such as Nanook of the North, Nosferatu, Singing in the Rain and Written on the Wind, the programmers aim to spark the interest of a younger generation, for whom the history of cinema is often uncharted territory. The ultimate weapon in the battle for their fragmented attention is the big screen: “To know what cinema is about, it is crucial to view films as they were meant to be seen, in their proper theatrical setting and with the full impact of the luminous image on a big screen,” Lewinsky and Wratschko write. And that seems to work. A jam-packed Piazza Maggiore collectively held its breath when the beautifully restored Nosferatu was hoisted out of his coffin.

Ritrovato, however, has not lost sight of its core task – to (re)discover and make available unknown films that are difficult to screen or are considered lost. Plenty of obscure films graced this year’s bill too. The programmers resolutely opted for a two-track approach, thus ensuring a pleasant viewing rhythm.

As usual, the programme took the form of a cinematic journey through time and space. The Time Machine and The Space Machine, which have become festival fixtures, presented films from long ago and far away. The Time Machine took us to 1902 and then to 1922. 1902 was a pivotal moment in the history of cinema. Technological developments encouraged filmmakers to ever more complex forms of experimentation, and public interest in the new medium was greater than ever. It was the year of Lumière and Pathé, but especially of Georges Méliès, who turned cinema into a narrative medium with A Trip to the Moon. Méliès made clear that film could not only depict (Lumière) but also imagine. The 20th century promised to be one of technological progress, and that appealed to the imagination. If technology can bring us moving images of the moon, will it also be able to take us to the moon? In Piazetta Pier Paolo Pasolini, Méliès’s A Trip to the Moon and other films from 1902 were magically brought to life by a smoking carbon arc projector.

In 1922, cinema was running at full speed, in the form of both realism and expressionism. In Die Gezeichneten (Carl Theodor Dreyer), Pay Day (Charles Chaplin) and Nanook of the North (Robert J. Flaherty) the cinematic narrative is at the service of (social) reality, revealing a number of structural contradictions within that reality. With Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau), The Woman from Nowhere (Louis Delluc) and Robin Hood (Allan Dwan), on the other hand, the filmmakers create their own world, in which fantasy, dream and symbolism give voice to their innermost emotions.

The Space Machine took us far beyond Bologna: from Germany to Japan by way of Yugoslavia. Towards the end of the Weimar Republic, Germany had a short but powerful period of musical comedies. The burgeoning sound-film came into its own completely with these playful odes to free and modern Weimar. The movement, which was mainly driven by Jewish filmmakers, producers and actors, was brutally ended by Hitler’s ascent to power. The programme The Last Laugh: German Musical Comedies 1930-1932 paid tribute to these Tonfilmlustspiele, a genre rooted in the operetta tradition of the 19th century, which for a while provided German cinemas with “a distinctly playful, sensual, frivolous and uninhibited sound” (Lukas Foerster). With eight feature films – including Who Takes Love Seriously? (Erich Engels, 1931), Her Majesty Love (Joe May, 1931) and I by Day, You by Night (Ludwig Berger, 1932) – and two short films, and with a focus on the smaller production houses Terra-Filmkunst and Super-Film, Ritrova offered a glimpse of what an alternative course of German (film) history might have looked like.

Founded in 1918, Yugoslavia had, like Weimar, a vibrant and innovative national cinema, which has received little attention. The section “Tell the Truth!” A View into Yugoslav Cinema tried to change that. The focus is on New Yugoslav Film filmmakers, whose critical cinema of the 1960s and 1970s debunked national myths and defied the established political order. Film became a political instrument for revealing the truth.

The Japanese director Kenji Misumi also knew how to bend genre conventions to his will. Kenji Misumi: An Instinctive Auteur took a closer look at his varied oeuvre, whose works are connected by a stylistic dexterity that clearly marks Misumi as an “auteur”. He subtly penetrates to the core of stylistic conventions in order to “detourn” their logic from the inside.

Ritrovato also took us beyond time and space... to paradise. The heading The Cinephiles’ Heaven grouped a number of sections for which the programmers delved deep into the film archives. Every year, the festival honours a number of important figures in film history by compiling a retrospective with the best available copies and restorations. This edition, the honour went to the Argentinean film maker Hugo Fregonese, the Italian actress Sophia Loren and the Austrian actor Peter Lorre. All three made a name for themselves in Hollywood.

For Fregonese, the programmers unearthed films from nine different archives. Hugo Fregonese (1908-87), an Italian immigrant in Argentina, is characterised by the title of his film Saddle Tramp. Like his protagonists, Fregonese travelled around and made films in various countries: in his native Argentina, the United States, Spain, Italy, the United Kingdom and West Germany. The programme had the ambition to rescue Fregonese from oblivion and to establish his name as an “auteur”. The selection that was shown only partly succeeds in doing so. It remains difficult to discern exactly what Fregonese wants to show us and especially from which point of view he wants to do that. There are traces of auteurship in his oeuvre, but they are faint. His characters often undertake an attempt at escape or an ambitious step towards a new life, an endeavour that mostly ends in catastrophe. Every film by Fregonese is the story of a breakout. In One Way Street (1950), doctor Frank Matson, played by James Mason, steals money from the mafia with which he hopes to start a new life in Mexico. Saddle Tramp (1950) tells the story of a cowboy who wants to try his luck in California but feels obliged to look after the children of a recently deceased friend. Hardly a Criminal (1949) is the only Argentine film in the selection and the last one Fregonese made there before leaving for Hollywood. Once again, the same idea: José Moran, an ordinary bank employee, discovers a loophole in the law which encourages him to commit “the perfect crime”. He embezzles a large sum of money from the bank where he works, with the idea of safely enjoying it after spending six years in prison. But his little plan turns out quite differently. In that respect, Black Tuesday (1954) seems to be the most archetypal Fregonese of the programme, just as A Man Escaped is sometimes characterised as the most “original” Bresson, as the film in which the auteur’s obsessions and portrayal of humankind are best expressed. In Black Tuesday, the notorious criminal Vincent Canelli, played by Edward G. Robinson, escapes from prison on the night his execution is scheduled. With the help of a fake reporter and Canelli’s girlfriend, the crook takes five hostages. Black Tuesday seems to be the ultimate Fregonese because it literally brings his obsession with claustrophobia and freedom into action. A locked up man tries to escape his fate, takes matters into his own hands. This fascination is also expressed in the mise-en-scène of his films. The spaces and landscapes in which the characters move are never described in detail, but they are compressed and depicted without depth. Fregonese very literally does this in the opening shot of Black Tuesday: the barred prison door appears as a frame within a frame. It seems impossible for Fregonese’s characters to escape their own image or fate; they remain trapped in their own frame.

The section on the world-famous Sophia Loren took a different approach. It aimed to shed new light on Loren with a programme that included not only the American films she became famous with internationally, but also Italian films in which she shows a completely different side of herself. Directed by Vittoria De Sica, Francesco Rosi and Ettore Scola, we see a vulnerable Loren, stripped of star power and playing complex characters. A striking discovery in that programme was George Cukor’s Heller in Pink Tights (1960), in which Loren plays the role of Angela Rossini, an actress in a travelling theatre company led by Tom Healy, played by Anthony Quinn. The film was introduced by Pierre Eugène, author at Cahiers du Cinéma. Eugène rightly characterised Heller as a film about actors and magicians, in which every character is an illusionist and spectacle is omnipresent. Everyone seems to be putting on a show for each other. Still, you also feel the tension around the notion of “auteur” in this film. Cukor is not a classic example, moving within the framework of genre cinema rather than outside of it. Eugène substantiated this with a text by Jean Domarchi, who wrote a “little eulogy for a great director” about Cukor in the Cahiers in 1960: “If parallels were still in fashion, I would compare him to Howard Hawks. He is similar at least in the following way: he is in cinema; he consciously accepts its constraints, duties and conventions, but makes a virtue of necessity. His range is not as wide as that of the brilliant Howard. His compass is more limited. He wasn’t the best in every genre, but he definitely did his share in some of them: mostly comedy, historical film, romantic film, theatrical adaptation and musical comedy.” But where Cukor does surpass his American colleagues, according to Domarchi, is in his tender evocation of the world of spectacle, of show business – which is reminiscent of Renoir’s colourful “theatre films”: The Golden Coach (1952), French Cancan (1955) and Paris Does Strange Things [or: Elena and Her Men] (1956). Eugène noted that in Heller, Cukor plays with the Technicolor palette like an illusionist, the colours fading towards the end of the film. Yet the spectacle also shows cracks, especially in its representation of horror (the three dead “Indians”), which is surprisingly modern. As Domarchi mentions in his text, it is mainly Cukor’s view of Sophia Loren that catches the eye. Cukor is not an auteur of great theories, but is mainly interested in experimenting with the available material, usually with famous actresses. “He takes Garbo or Judy Holliday and wonders: ‘What would be the effect of Garbo, or Judy Holliday, in a role for which she is not cut out?’” Just as he gave Judy Garland an entirely new face in A Star is Born (1954), he offers a different view of Sophia Loren in Heller.

Our image of Peter Lorre, like that of Sophia Loren, was equally determined by the American studios, which did not hesitate to typecast him because of his slightly unusual appearance. Behind these Hollywood stereotypes, as shown by the festival’s selection, there is a brilliant actor. Lorre – “the greatest living actor” according to Charlie Chaplin – only had a few roles that gave him the room to use his emotional range. In The Man Who Knew Too Much (Alfred Hitchcock, 1934), he digs deep into the dark psyche of his troubled character, while I Was an Adventuress (Gregory Ratoff, 1940) is proof of his comic talent.

Recovered and Restored is the most anticipated section. This “festival within the festival”, as curator and founder Gian Luca Farinelli calls it, shows the best that film archives and laboratories worldwide have to offer. Unlike the other sections, which are thematically curated and analyse and illuminate film history from a specific angle, Recovered and Restored uses only one criterion: the irrefutable value of a restoration or discovery within the framework of film history. The section is about a certain necessity, aimed at securing more than 100 years of cinema. If the spirit of the early Ritrovato years still haunts the festival, this is where it happens.

An oft-repeated criticism of Recovered and Restored is that its lack of thematic coherence inevitably leads to a homogeneous stream of films untethered to historical, aesthetic and production contexts. It is said to reduce film history to a succession of highlights. The value of the section, however, lies in the way it engages in a dialogue with history, shaping the past from the present. The canon is not merely reproduced, but also put into perspective and questioned. Recovered and Restored reinterprets a film history that is constantly changing. Some films, such as Franco Rossi’s Smog from 1962, are shown again for the first time after decades of flying under the radar. Smog is one of the undeniable discoveries of the festival. Rossi is best known for the television series he made for Italian television at the end of his career. The fact that his feature films received little attention is largely due to distribution problems that forced his work into obscurity. When Rossi’s production company Titanus ran into financial difficulties, it decided to sell a number of films to MGM, including Smog. Despite the fact that Smog had successfully opened the Venice Film Festival, MGM decided to stop distributing the film, leaving the film canisters untouched for 60 years. An unfortunate story, as Smog contains all the elements for a prominent place within Italian modernism. The film shows 48 hours in the life of Italian lawyer Vittorio Ciocchetti who is stuck in Los Angeles because of a delayed flight to Mexico. Temporarily displaced, the Italian first roams the airport and then, as the only pedestrian, the deserted streets of the American car city. His encounters make it clear that he is not the only one who is lost. The compatriots who take him in tow likewise seem to lack a goal, and the Americans seem alienated from themselves and their surroundings. A thick layer of smog hides a world in which everyone is in transit; a transit space offering no way of settling. Rossi expresses the alienating relationship with the vast urban space in a visual language that is reminiscent of the cool gaze of his contemporary and friend Antonioni. The montage allows for emptiness and the mise-en-scène emphasises the characters’ inability to get a grip on their surroundings. At one point, the meandering camera even loses sight of the protagonist completely. Along with the narrative, Vittorio disappears from view. The film then focuses on the beautiful character Gabriella, wonderfully played by Annie Giardot. Whereas Antonioni’s slow gaze inevitably brings with it a certain heaviness, Rossi manages to maintain a certain lightness. The humour of this satirical portrait of American society balances between admiration and condemnation.

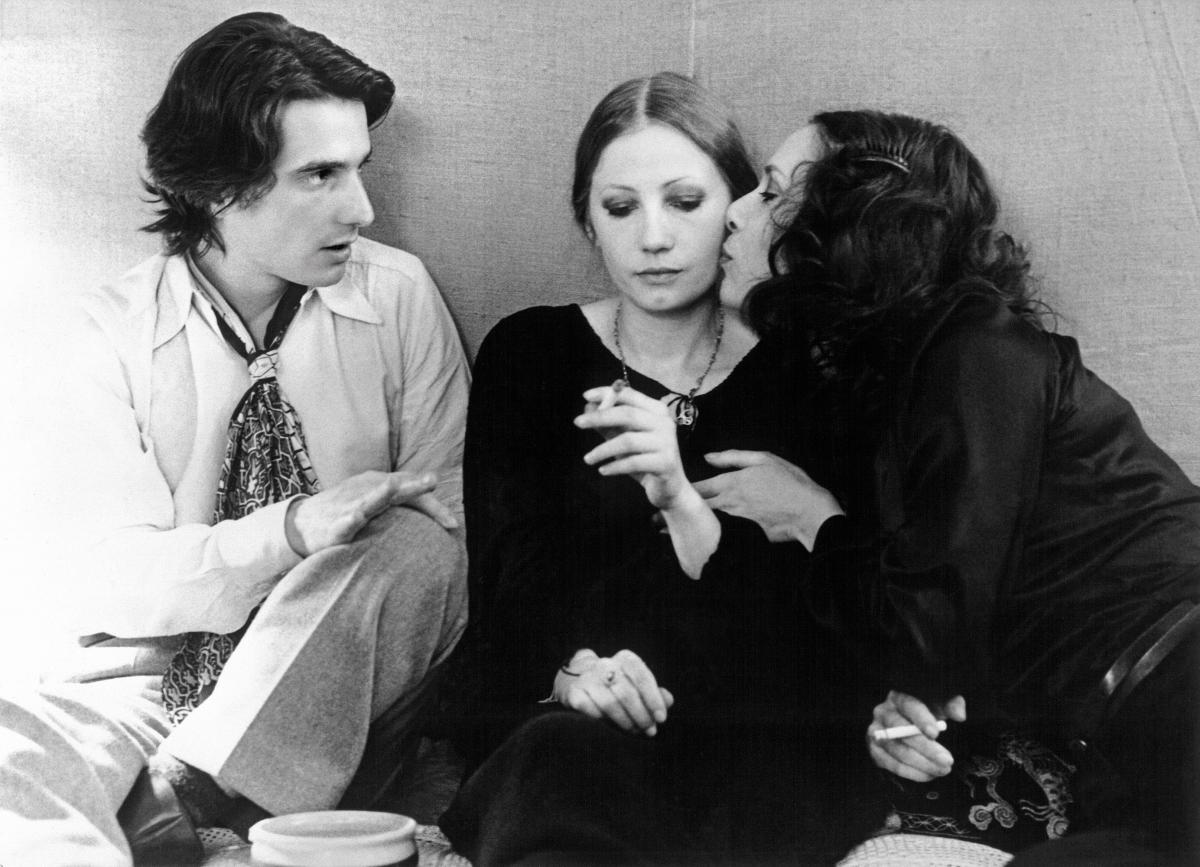

Other films had limited availability, were in poor condition or had been incorrectly edited. Foolish Wives, for instance, was shown in its original 1922 montage, as intended by Erich Von Stroheim. Similarly, the restoration of Jean Eustache’s The Mother and the Whore (1973) offered a viewing experience that is very different from the deplorable versions that had been circulating. So many people discovered the film through a digitised VHS copy, whose poor quality added to its value, but the recent 4K restoration of the film lends it a more classic cinematic quality in which the use of lenses and the composition are especially striking. Despite this “recalibration”, The Mother and the Whore remains a masterpiece pure and simple, which can now finally and fortunately be (re)discovered by a wider audience. The Mother and the Whore is a remarkable film because it is both the ultimate Nouvelle Vague film, the film “Rivette, Godard, Rohmer and Truffaut dreamed of” (Olivier Assayas), and the epitaph of the French film movement that emerged in the 1950s. In that sense, it is a film that “arrives too late”, a film about an aftermath. “Without it, we would not have a face to attach to the memory of the lost children of May ’68,” Serge Daney said.

Another moving moment was the presentation of the restoration of Shoeshine, Vittoria De Sica’s 1946 classic. Two boys, Giuseppe and Raffaele, shine shoes in post-war Rome and save up to buy a horse together. Because of their involvement in a burglary, they end up in a reformatory. They are put in different cells, which takes a devastating toll on their friendship. The actor who played the boy Giuseppi, Rinaldo Smordoni, attended the presentation at the festival. He spoke briefly about how he had been cast on the street, about how De Sica had asked him if he could cry well, to which he replied, “I’m very good at crying!” and was immediately offered the role. The producer’s grandson was also present. Shoesine was the first film to win an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. The Oscar statuette was proudly handed to Smordoni, now 89 years old.

![(10) Dolgie provody [The Long Farewell] (Kira Muratova, 1971) (10) Dolgie provody [The Long Farewell] (Kira Muratova, 1971)](/sites/default/files/Long%20Goodbye%201_0.jpg)

Two early films by the Romanian-Russian-Ukrainian Kira Muratova were restored. A double bill of Brief Encounters (1967), Muratova’s debut film, and Alice Rohrwacher’s The Pupils made for a well-filled Piazza Maggiore. Rohrwacher’s conventional narrative style, however, paled in comparison to Muratova’s idiosyncratic visual language, which was already clearly in the making in Brief Encounters but really came into its own in her second film, The Long Farewell (1971). Evgenia, a single mother, has trouble with her adolescent son. When he announces that he wants to live with his father, her fears and insecurities take over. The film explores the inner state of mind of the protagonist, who is forced to re-evaluate her identity as a mother. Not the narrative, but the editing is Muratova’s main instrument in dissecting Evgenia’s despair. Repetition and fast cuts create a hurried and restless rhythm that expresses the emotional state of the characters. Although the film breaks with narrative conventions, it never becomes gratuitous experimentation. Muratova describes her own working method as follows: “Hidden in the footage, there is one method of editing, one optimal use of all possibilities. That’s what I try to get to.” The form is a necessary consequence of the content and in turn contributes to that same content. It is like listening to a language you hear for the first time and yet understand, without knowing its grammar or vocabulary. The Long Farewell appeals on an affective, pre-linguistic level. Although the film does not contain any explicit political references, its release in 1971 was blocked by Moscow. Aesthetically, it deviated too far from socialist realism. Muratova’s stylistic radicalism made the film suspect, and only in 1987 would the film finally be seen on the screen.

![(11) Kahdeksan surmanluotia [Eight Deadly Shots] (Mikko Niskanens, 1972) (11) Kahdeksan surmanluotia [Eight Deadly Shots] (Mikko Niskanens, 1972)](/sites/default/files/Kahdeksan-surmanluotia_3.jpg)

One of the greatest discoveries this year was Mikko Niskanen’s Eight Deadly Shots (1972), originally broadcast in Finland as a four-part television series but presented in Bologna as a five-and-a-half-hour film composed of four parts. Peter von Bagh, Finnish film historian and former artistic director of Ritrovato (he died in 2014), was a tireless advocate for the restoration of this serial film, which had a great influence on a whole generation of Finnish filmmakers, including Aki Kaurismäki. The entire film is structured as a flashback: Pasi, a peasant, shoots four policemen who come to arrest him – eight deadly shots. The film then outlines the events that will lead to the tragic shooting. Pasi sinks in an ever deeper well of poverty and alcoholism, gets into trouble with the police and tax officials, while domestic quarrels intensify. Eight Deadly Shots is constructed as a chronicle, albeit in different registers: documentary observations of the life of a peasant family alternate with lyrical impressions that reference the work of Alexander Dovzhenko, while more dramatic scenes call to mind the independent American cinema of the late 1960s. Certain scenes with the poor peasants even bring to mind Walker Evan’s pictures of the Great Depression. What ultimately makes the film so powerful is the fact that it manages to avoid becoming a humanist, psychological portrait of a man struggling with his alcohol consumption, and that it is driven above all by a sociological ambition that, as Olaf Möller rightly points out, uses techniques reminiscent of the 19th-century novels of Emile Zola. By focusing on the repetitiveness of the daily life of this simple peasant, the film reveals the destructive power of a social order that would transform Finland. Pasi’s crime is more than an offence committed by an individual, embedded as it is in an entire chain of social upheavals.

There was a striking amount of attention for early cinema this year. Almost half of the Recovered and Restored screenings were silent films, the absolute highlight being In the Night (1930), considered to be the “last French silent film”. Charles Vanel, who was mainly active as an actor, tried his hand at directing with this drama about a French working-class family. His life’s work, however, was completely drowned out by the sound-film that was emerging at the time. Vanel seemed to feel the new technology breathing down his neck. The image being his most important means of expression, he went for a well thought-out mise-en-scène and inventive montage. The public had little interest in this “outdated” film form and In the Night died a silent death. In Piazza Maggiore, the film was accompanied by the experimental electronics of the Finnish band Cleaning Woman. Once again, the sound drowned out the image. It was one of the few times the festival completely missed its mark. But even this wrong note did not detract from the wonderful experience of diving into the night with Vanel’s poetic images and thousands of spectators in Piazza Maggiore.

Image (1) and (4) from Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens (F.W. Murnau, 1922)

Image (2) from Le voyage dans la lune (Georges Méliès, 1902)

Image (3) from Ihre Majestät die Liebe (Joe May, 1931)

Image (5) from Black Tuesday (Hugo Fregonese, 1954)

Image (6) from Heller in Pink Tights (George Cukor, 1960)

Image (7) from I Was an Adventuress (Gregory Ratoff, 1940)

Image (8) from Smog (Franco Rossi, 1962)

Image (9) from La maman et la putain (Jean Eustache, 1973)

Image (10) from Dolgie provody [The Long Farewell] (Kira Muratova, 1971)

Image (12) from Dans la nuit (Charles Vanel, 1930)