Week 24/2024

“Do I really exist or is this just a dream?” my six-year-old daughter recently asked me, out of the blue, when I put her to bed. In the final scene of Eyes Wide Shut (1999), Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman’s little daughter disappears unnoticed while the couple muses about whether, after surviving all their “adventures”, “they were real or only a dream.” Cruise replies that ”no dream is ever just a dream.” With the film, Stanley Kubrick transposed the story of Arthur Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle (1926) from Sigmund Freud’s fin-de-siècle Vienna to contemporary New York. In his review at the time, filmmaker and teacher Herman Asselberghs found Eyes Wide Shut to be “too much of Freud, too little of Lacan.”

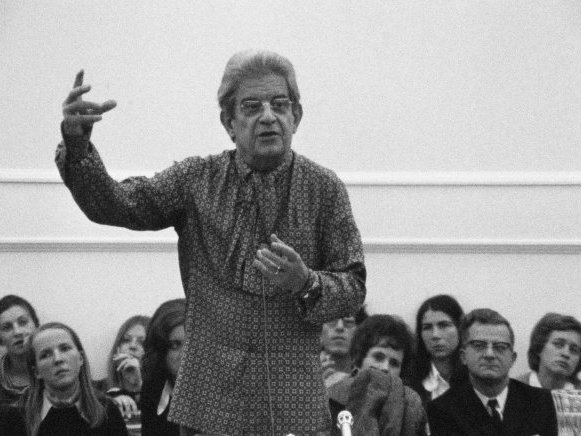

On Thursday in Cinema Palace, Le P’tit Ciné organizes an exceptional screening of Jacques Lacan parle (1972). Restored for the occasion, the film is a rare record of Lacan’s 1972 lecture at the Catholic University of Louvain (UCL) where a young Situationist disrupts the 71-year-old psychoanalyst and vandalises his notes with water and flour. In a conversation with filmmaker Jorge Leon, the Belgian documentarian Françoise Wolff will present this film she made as a young RTBF journalist.

Jean-Pierre Melville’s self-invented Buddhist epigraph that opens Le cercle rouge (1970) states that people who are meant to meet will eventually do so “in the red circle.” And so was the fate of the students sitting around Lacan or the secret society’s red carpet circle in Eyes Wide Shut. Kubrick said he gave up doing crime films because Melville already reached perfection with Bob le flambeur (1956). Yet Olivier Père’s reflection on Le cercle rouge equally counts for Kubrick’s final and finest work: “He doesn't film reality, but ideas, frozen dreams, bleak fantasies in maniacal detail.” To which Melville said: “I'm no documentarian; a film is first and foremost a dream.”