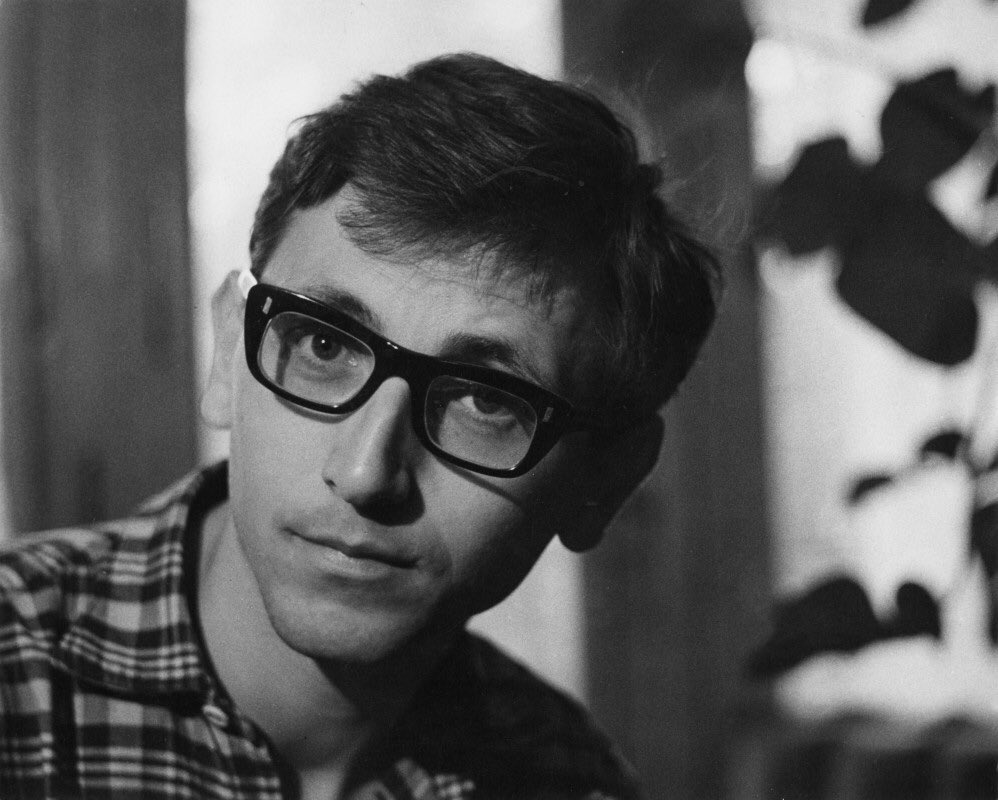

Jiří Menzel (1938-2020)

Czech filmmaker Jiří Menzel has died at age 82. Menzel was destined for the theatre but was rejected at the theatre school because of, in his own words, “lack of talent” and resigned to studying cinema. Part of the Czech New Wave of filmmakers of the sixties of which also Miloš Forman and Vera Chytilová were part, Menzel had his breakthrough with his debut Ostře sledované vlaky [Closely Watched Trains] (1966), which won him the Academy Award for best foreign-language film. The film tells the comical story of a young train dispatcher in German-occupied Czechoslovakia during the Second War and was based on a novel by Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal. “What it appears Mr. Menzel is aiming at all through his film,” American film critic Bosley Crowther wrote, ”is just a wonderfully sly, sardonic picture of the embarrassments of a youth coming of age in a peculiarly innocent yet worldly provincial environment. [...] The charm of his film is in the quietness and slyness of his earthy comedy, the wonderful finesse of understatements, the wise and humorous understanding of primal sex. And it is in the brilliance with which he counterpoints the casual affairs of his country characters with the realness, the urgency and significance of those passing trains.” In addition to his first feature film, Menzel adapted Hrabal in the films Skřivánci na niti [Larks on a String] (1969), Postřižiny [Cutting it Short] (1981), Slavnosti sněženek [The Snowdrop Festival] (1984) and Obsluhoval jsem anglického krále [I Served the King of England] (2006). Reflecting on this succes, Menzel said in 2006 that he "had more luck than reason, more than all the prizes and medals I received for this movie, I valued the lifelong friendship with Hrabal.”

But Menzel barely benefited from its success, as the Soviet invasion crushed the liberal ambitions of the Prague Spring. Like other directors of his generation, he faced censorship by Communist authorities. His 1969 film, Larks on a String, depicting a group of politically persecuted people forced to work in a scrapyard, was not released until 1990. It went on to win the Golden Bear at the 1990 Berlin International Film Festival in. Menzel did not return behind the camera until 1974. Unlike Forman, he did not emigrate to the United States to pursue a career, out of conviction and solidarity with his colleagues back home as much as out of coercion (his passport was confiscated). “Great films were made under censorship, even in the United States, when you couldn’t show people kissing. Freedom has this side effect where, because everything becomes possible, you lack goals and direction. Creation always needs limits. It is born out of conflict. If you don’t have limits, you’re talking nonsense.”1

“Menzel is nothing like this character, but one senses his life story would make a similar sort of movie. Like most filmmakers who grew up behind the Iron Curtain, his career has been marked by interruptions, reverses and entanglements with communist authorities – in all of which Menzel seems to have seen the funny side. Or at least the ironic side. You could insert the word ‘ironically’ into Menzel’s biography, at virtually any point, it seems. He originally wanted to be a theatre director, for example, but was not accepted ‘for lack of talent’ and enrolled at film school instead. In later years (ironically), during periods when he has been unable to make films, he has worked extensively in theatre. His colleagues at film school included the future forerunners of the Czech New Wave: Jan Nemec, Jaromil Jires, and Vera Chytilová among others, who enlisted Menzel to direct a segment of Pearls of the Deep, an adaptation of short stories by renowned Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal. ‘I was not a very distinguished student,’ he says, ‘I was the youngest. I was innocent. I had no ambitions.’ And yet it was Menzel who went on to become the chief interpreter of Hrabal’s works, starting with Closely Observed Trains. Based on Hrabal’s own experiences, it is set in the 1940s, and depicts a naïve railway apprentice's quest for sexual liberation, which is conflated with the wider struggle for national liberation from the Nazis. Although the movie ends with a tragic (and, yes, ironic) act of heroism, politics are largely on the periphery, with gentle, down-to-earth comedy to the fore. ‘Good comedy should be about serious things,’ he says. ‘If you start to talk about serious things too seriously, you end up being ridiculous.’ Menzel's blend of compassionate, lyrical realism and French New Wave-influenced stylistic boldness made an impact, particularly on British filmmakers like Ken Loach and, later, Bill Forsyth, director of Local Hero. [...] Censorship did not publicly exist behind the Iron Curtain, he explains, but there state control over Eastern Bloc filmmaking operated on myriad levels: approval of the initial idea and the script, the presence of an ‘editor’ on set, postproduction monitoring, cuts to the final print, controlled levels of distribution, ‘and finally, even if you accepted all this and your film was ready to be shown, they would find some stupid reason for changing it, because if they didn’t change anything, people might think they weren't needed at all.’”

Steve Rose2

- 1Léo Soesanto, “Mort du cinéaste Jiri Menzel, figure de la Nouvelle Vague tchécoslovaque,” Libération, 7 September 2020.

- 2Steve Rose, “Irony Man,” The Guardian, 9 May 2008.