Streets of Parisian Fiction

The Adventurers of ’80s Cinema

“She is at home everywhere, transforming enclosed, oppressive spaces, thought to be unsettling, into familiar places, temporary homes, where she digs her hole, arranges her place.”1

These words belong to the filmmaker Danièle Dubroux. They were printed in Cahiers du Cinéma and used to describe the forcefulness of the title character in Marie-Claude Treilhou’s debut feature film, Simone Barbès ou la vertu (1980). In hindsight, Dubroux’s words did more than that. They tapped into an energy that ran through the late ’70s and ’80s as an undercurrent, taken on in myriad ways by filmmakers. By turning the streets of Paris into temporary homes, these filmmakers engaged in the alchemistic activity of fiction. They anchored their films in specific locations that, at the same time, were inverted into spaces of adventure. Here, playfulness and indeterminacy rule. Characters mold the spaces they inhabit as they go along, making the structures of the films vibrate as living things – as integral parts of the films’ very fabric instead of just a container for them. These filmmakers put confidence and pleasure back into storytelling and made it impressionable towards reality and class relations.

Treilhou, Jean-Claude Biette, Jean-Claude Guiguet, Gérard Frot-Coutaz, Noël Simsolo, and the other filmmakers tied to Paul Vecchiali’s production company Diagonale made this sensibility come alive. Axelle Ropert, a true champion of these films, captured the joy of their world in a recent essay: “In the Diagonale films, it feels good to talk, sing, love, suffer, have bizarre affairs, strange relationships, secrets, and form communities with weird rules.”2 It’s a cinema that restores some of the sentiments, looks, and voices of the 1930s popular cinema. It’s fair to its characters and faithful to the stock company of actors that embody them: It doesn’t matter if a gag is pulled off entirely or if a note is hit perfectly because the films aren’t trying to convince you of anything. The films sing to their own tune, and while we might not always know what the characters are doing or where they’re going, they do, and that’s enough. And indeed, it’s a cinema of secrecy. Somehow, these filmmakers pass on their secrets to us intact, sotto voce. We carry them around without knowing what they mean, and yet we feel included – as if we know at least half of the password to their underground networks.

These streets of Parisian fiction give the impression of endlessness. Beyond the Diagonale films, there are other side streets, passageways, alleys, tunnels, and backstreets leading to yet another image, another secret. Look around the corner, and you’ll find films of a like-minded nature. Consider, for example, the psychogeography of Jacques Rivette’s films, particularly Le pont du Nord (1981) or the disintegration of space that Raúl Ruiz lets loose in his short Zig-Zag – le jeu de l’oie (Une fiction didactique à propos de la cartographie) (1980). A mysterious woman arrives at Gare de l’Est in Danielle Jaeggi’s La fille de Prague avec un sac très lourd (1979). In her heavy bag, she carries illegal texts, confiscated tapes, films, and other memory objects that speak to the psychical reality of the political past and present. With Un dessert pour Constance (1981), Sarah Maldoror laid out the lives of two African street sweepers who come upon an old cookbook of French cuisine. Conversations sparked by the culinary world intermingle with the historical monuments the two characters are surrounded by. Sidney Sokhona applied strategies of observational comedy to his indignant depiction of labor rights for African immigrants in Safrana ou le droit à la parole (1978). Then there are the intense emotions of the community of dealers, users, and sex workers that occupy Juliet Berto and Jean-Henri Roger’s Neige (1981), and the doomed lovers traversing Samuel Fuller’s Les voleurs de la nuit (1984) and Robert Kramer’s À toute allure (1982). Other filmmakers devoted themselves to giving form and fiction to the quiet seriousness of adolescence. Orphans, lonely souls, rejects, and plain ordinary kids left to their own devices walk these streets, which are very different from the ones adults walk. The children and young adults see and know more than they can express, and it is precisely the experience of this unsayable threshold that the films evoke. From the eyes of a little girl, the cityscape and the Seine of Catherine Binet’s Les jeux de la comtesse Dolingen de Gratz (1981) unfold as a baroque Freudian dream. In Laurent Perrin’s Passage secret (1985), murmuring kids live restlessly in flux, running from rooftops to catacombs, and let’s not forget the profound loneliness of the roller-skating girl in Michèle Rosier’s Embrasse-moi (1989) or the two banlieue dreamers of Serge Le Péron’s Laisse béton (1984). Youthful charm flourishes in Louis Skorecki’s Les cinéphiles: Le retour du Jean (1989), in which cinephilia is developed through conversations with friends and dates in public spaces. By contrast, in Luc Moullet’s Les sièges de l’Alcazar (1989), an adult’s amorous cinephilia can only grow in front of the screen.

These filmmakers were all ciné-adventurers. Which is not the same as conquerors. It was never about claiming others’ space but carving out a new one for themselves. Modestly and self-assuredly, they were each content with mapping the fictions of a single street or two. This way, they managed “to grant a filmic dignity to that which didn’t have any,” as Serge Daney once remarked about the true meaning of realism.3 They created images where none existed. Therein lie their politics. The ’80s cemented the return of fiction in French cinema and the reembrace of the Hollywoodian cinephilia of the ’50s, but that doesn’t mean that the lessons of May ’68 were entirely forgotten.

Many filmmakers have already been mentioned, and many others could be named, but let’s limit ourselves to looking closer at three: Marie-Claude Treilhou, Julius-Amédé Laou, and Pierre Zucca.

Treilhou’s Simone Barbès ou la vertu takes place throughout one night and in three locations: the porn theater where Barbès works, the lesbian bar where her girlfriend works, and a car where she and a stranger share their thoughts of solitude. Between each location there is an intermezzo of exterior shots, a pocket of fresh air. These brief inserts do more than structure the film. They linger on long after the scenes have moved inside. The film opens with a set of static establishing shots of the Montparnasse-based theater. Instead of simply cutting to Barbès in the foyer, Treilhou connects the outside and inside through a handheld camera movement. In this shot – the only handheld one in the sequence! – the camera attains bodily presence, sleazily moving closer and closer toward the glass door entrance, lurking at Barbès from the dark, mirroring the light installation hanging on the foyer’s wall: a pair of eyes. Treilhou plays it straight, but this connecting shot sets up the two main features of the first location: dry humor and voyeurism.

Later, Barbès is at the lesbian bar. It’s a more self-enclosed space than the cinema, seemingly shut off from the outside and its male gaze. And yet, there’s the entrance door: As the camera glides between Barbès and the vaudevillian life of the bar – a performance, a cabaret, a concert, fights, kisses, disappointed gazes – a herculean doorman plods along in the background, opening and closing the door. What’s he doing? It’s unclear. But certainly, there are secrets beyond the door. That is, other fictions we are not a part of. The great unknown.

Lastly, the car. An entangled space of interior and exterior. The camera is mounted on the hood of the car, turned towards the two strangers as they drive through Paris. He cries, she smiles, and they quietly appreciate the brief encounter. They talk about places to go, but the possible adventures never happen. Barbès is dropped off at home, the car drives on, and the film ends with a wide shot of a desolate street and the Canal Saint-Denis running across. A documentary image of the city as is? Then, suddenly, the streetlights all turn off, like a curtain call for the credits, enveloping it all in the promise of fiction. You wouldn’t know it by just seeing the film, but the documentary value remains: The streetlights went off because the municipal protocol required them to do so at dawn. We’ll have to wait till nightfall for Treilhou’s nocturnal world to reemerge.

“Blow it all up! This whole fucking world of freaks!” Richard yells from the window of his apartment while firing off an imaginary machine gun. It’s this fiery image that first meets us in Julius-Amédé Laou’s Mélodie de brumes à Paris (1985), reminiscent in composition and intensity of the showdown in Howard Hawks’s Scarface (1932). Except here, Richard is not trying to shoot his way out of the building but out of his trauma. He’s a man from the Caribbean diaspora reliving the experiences of having fought for France in Algeria. Then, a cut: a woman’s close-up, sitting next to Richard in the apartment, knitting. This is the magic of Laou’s film. People and spaces aren’t established or introduced; they appear with the suddenness of a cut. Through acute montage, Laou can also unearth spaces of the past and allow Richard to walk with zombies. This also means that Laou’s Paris is one of intense confrontation. While Richard dissipates further and further into the past, the blatant racism experienced in public spaces continually jolts him back to the present. The friction is never solved; it expands, and threads of fiction-truths are further entangled. All in twenty-two minutes.

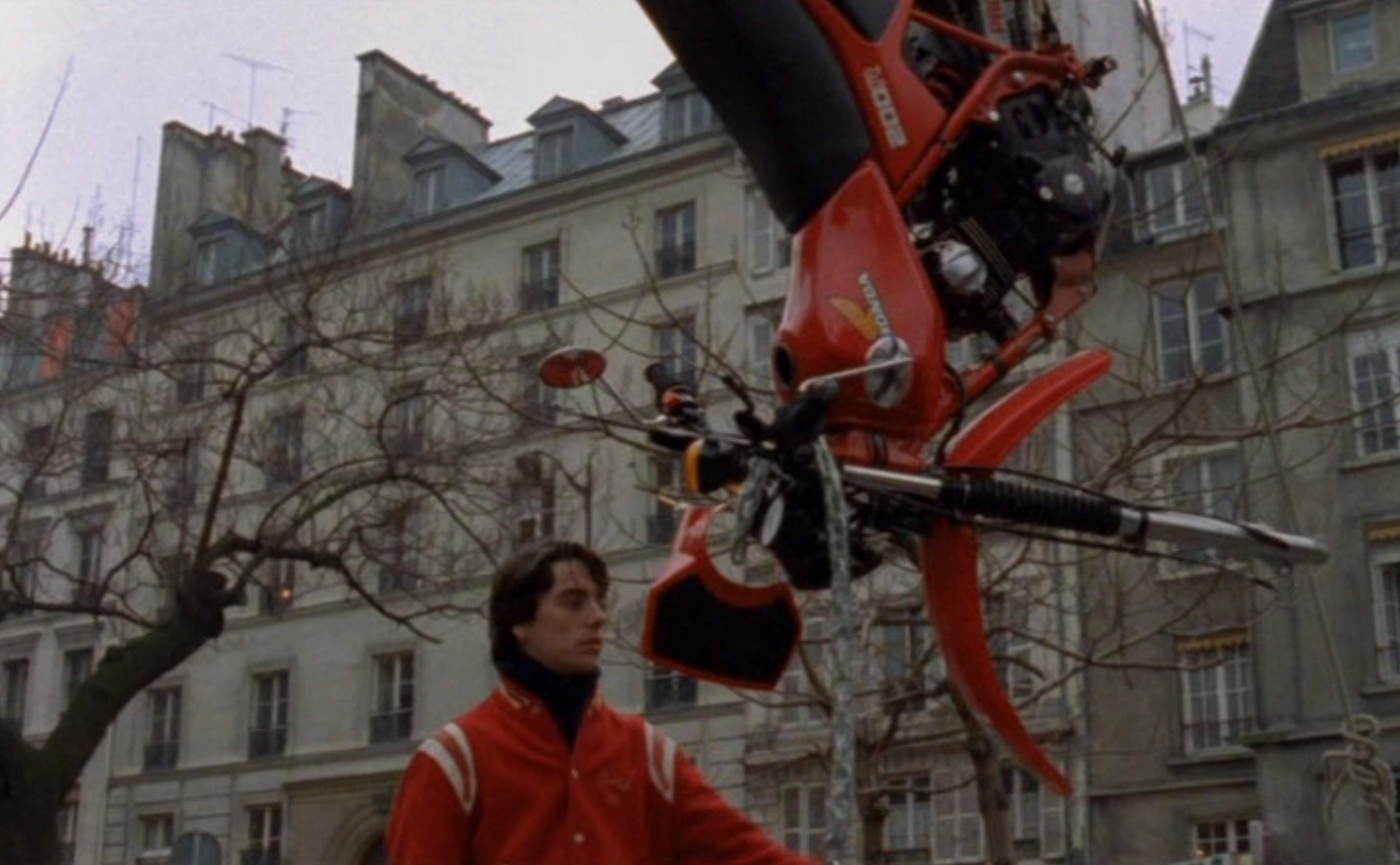

The motorcycle crew seems to drive in circles. Whether on the square in front of Gare Montparnasse or through the cobblestone avenues by the Pantheon, they end up where they started. They act as if they have a purpose, but they’re just spinning their wheels. The inner workings of this crew reflect the overall shape of the film to which it belongs, Pierre Zucca’s Rouge-gorge (1985). A young woman, Reine Ducasse, moves back to Paris and into her father’s apartment. One guy, another guy, many guys show their interest in her. Like the forcefield of a vortex, she subsumes the lives around her, including one of the bikers. She, too, gets caught up in the swirl of attraction. And with it, conspiracies and lies arise, all with an empty center. The whirring and rattling sounds of the bikes are nearly the only thing that Zucca expresses with a tangible matter-of-factness. The visible world is covered with veils of illusions, and Zucca draws invisible lines between the shadow people hidden in the texture of society. A modern world of briefcases with nothing in them, fake passports, MacGuffins, stocks, and counterfeit money. Zucca can make the city feel like a paper-thin set piece on a backlot, but he never does it overtly. There’s a quietness to it all. When Serge Bozon presented the film in New York in 2011, he quoted Louis Skorecki’s review from Libération: “He [Zucca] created a kind of philosophy equivalent to that of Hollywood B movies, a mannerist manner for making himself anonymous while inventing unusual poses.”4

Rouge-gorge is a crime film with the air of an adventure, even that of a swashbuckler. During a hideout, Charles, one of the bikers, finds himself in a repertory cinema screening Treasure Island (Yevgeni Fridman, 1971). Reine is entranced by maps of the past at the library. And it is not just money the characters are interested in, but gold. In a marvelous scene, Reine’s father lets gold coins fall out of a drawstring purse and into a water-filled sink. As two amazed fortune seekers, the light of the coins bounces back on Reine and her father’s faces. And it is obvious that Zucca is amazed at looking at them as something strange and promising. “I don’t understand them, but I want to see it,” he explained in a radio interview when discussing the characters’ actions.5 In his review for Cahiers du cinéma, Pascal Bonitzer connects these adventurous ideas to a fundamental aspect of cinema: “Zucca has a childlike passion for fakery, an erotic passion for lies, of which cinema becomes the reflection and the catalyst. Lying is a fetish: we desire a woman because she lies [...] Conversely, we lie because we desire.”6 Lies, desires, childlike passions. These are the values of cinephilia and the tradition of classical adventure films that Zucca adopts in his film; through them, he offers us a way of seeing. Although I’m not sure if Zucca was a fan of George Stevens’s films, it’s nevertheless Stevens’s words on cinema-going that echo when I think of Rouge-gorge: “Kids come to live an hour of the life they haven’t yet lived, and oldsters to live the life they’ve missed.”7 Rouge-gorge allows us to be both the kids and oldsters, living lives that are both our own and not.

Zucca – and the filmmakers mentioned above – bring life and cinema together and create multiple fictions that run parallel through childhood and adult life, extending the passions of the screen onto the streets. Few have written as eloquently on this thwarted experience of living with cinema as the Spanish film critic Miguel Mariás. Let it be his words that close this text:

“That is why we have learned so much from the cinema, not only about the cinema itself but about life in general. We owe the movies not only very good times and a handful of memories and emotions and laughter, but many lessons that were never intended to be lessons, that we ourselves accepted as such, without telling anyone, without asking permission.”8

- 1Danièle Dubroux, “Simone Barbès ou la vertu,” Cahiers du Cinéma 309 (1980): 42 [translation mine].

- 2Axelle Ropert, “Diagonale and Us,” Screen Slate, 2023.

- 3Serge Daney, “Eloge d'Emma Thiers Sous-titre,” Cahiers du Cinéma 285 (1978): 31. Translated by Laurent Kretzschmar and Jack Seibert.

- 4Louis Skorecki, quoted by Serge Bozon. 2011. Film at Lincoln Center.

- 5Pierre Zucca, “Le cinéma des cinéastes,” 1985 [translation mine].

- 6Pascal Bonitzer, “Usage de faux,” Cahiers du Cinéma 369 (1985) : 58-59 [translation mine].

- 7George Stevens, as quoted by George Stevens Jr. in George Stevens: A Filmmaker’s Journey (Stevens Jr., 1984).

- 8Miguel Marias, “El niño cinéfilo,” Nickel Odeon 11 (Summer 1998); posted on author’s personal blog, October 9, 2023, https://miguelmarias.blogspot.com/2023/10/el-nino-cinefilo.html [translation mine].

The author would like to thank Julius Lagoutte Larsen.