The First Screenings

125 years ago, on March 22nd, 1895, the first film in history was projected for a crowd of about ten people. During a special gathering in the Société d’Encouragement à l’Industrie Nationale, Louis Lumière projected his first film: Sortie des ouvriers de l’usine de Monplaisir. Building on the inventions of Etienne-Jules Marey, Charles-Émile Reynaud and Thomas Edison, the brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière had created a so-called “cinematograph”, a device with which one could make chronophotographic prints and look at them in sequence. The device was versatile: images could both be captured and projected. Its first real presentation, and also the first real triumph of cinematography, took place on December 28th, 1895, in the basement of the Grand Café on the Boulevard des Capucines in Paris. In this first public and commercial event, a dozen films were shown and received with wonder and perplexity by the spectators present. Lumière’s cinematograph had made its first conquest. Cinema had penetrated public life; soon every screening would be packed to the rafters.

The brothers Lumière particularly saw the cinematograph as a tool to observe and capture natural phenomena; initially the device was mainly used to film quotidian scenes. None of these sequences had any “showpiece quality.” Rather, they were little “documentaries”, almost designed as scientific observations. This changed with L’arroseur arrosé, a movie put together by Louis Lumière, which can be considered the first “dramatic” piece of film. Even though the brothers were not fully conscious of this fact, L’arroseur became the first film sequence to reveal the artistic possibilities of the new medium. Made with diligent care for substance it was also the first “composed” piece of film, a movie with its own script. Thus one witnessed the birth, almost inadvertedly, of the art of film.

On the occasion of this 125th birthday, Sabzian is publishing a series of translated fragments from Histoire du cinématographe: de ses origines à nos jours (1925) by Georges-Michel Coissac, where, amongst other things, the author narrates the history of these marvellous first film screenings.

Gerard-Jan Claes

We think it is worth recalling here that until the opening of the basement of the Grand-Café, no other hand operated the crank, made negatives, printed and developed positives; all this work was done by Mr. Louis Lumière himself who – by the way – after shooting L’arrivée d’un train, in La Ciotat station, a Barque sortant du port, etc., used the beautiful Mediterranean sky to print the positives by simply pointing his camera at a wall, lit by the sun and covered with white paper.

Here are now, in accordance with the dates, the screenings which consecrated the cinematograph:

1. Special meeting at the Société d’Encouragement à l’Industrie Nationale, under the chairmanship of Mr. Mascart, President of the Académie des sciences, in Paris, rue de Rennes 42, on March 22, 1895. Lecture by Mr. Louis Lumière on the photographic industry, after the projection of his first film: Sortie des ouvriers de l’usine de Monplaisir;

2. Congress of the Sociétés photographiques of France, in Lyon, hall of the Palais de la Bourse, June 10, 1895;

3. At Berrier and Millet, place Bellecour, Lyon, on June 12, 1895, on the occasion of the banquet which brought together the members of the aforementioned Congress. At these two meetings, chaired by Mr. Janssen, member of the Institute, director of the Paris Observatory, the following two films were projected on the screen, with explanations: 1. Promenade des congressistes sur les borde de la Saône; 2. M. Janssen discutant avec son ami Lagrange, general councillor of the Rhône county;

4. Private screening at the Revue générale des Sciences pures et appliqués, in Paris, on Thursday, July 11, 1895, in front of the elite of the scholarly world. As early as July 13, 1895, Mr. Louis Olivier, director of this important publication, addressed the following letter to Louis Lumière, which we deem interesting to quote in extenso:

Paris, rue de Provence 34, July 13, 1895

Dear Sir,

I feel the need to tell you again how much pleasure you’ve given me and my friends. Last night and this morning, I heard from all sides about this brilliant presentation, which charmed all the spectators, as their cheers, in fact, have shown you. We were delighted to see these marvels, absolutely unheard of in Paris, and which, I have no doubt, will quickly spread throughout the country.

For me, I am infinitely grateful to you for providing my guests the premiere of this beautiful spectacle, which marks a new and very important stage in the photographic sciences. Allow me, dear Sir, to compliment you and your brother very warmly on the magnificent result you have achieved and to express to you all the joy I have had in viewing it.

I am also sending you all the letters that I have received in response to my invitations, classified by yes and no. Several people who had said yes did not come; others who had not replied came. The whole Bouvier banquet came in a bunch. All in all, about 150 people appeared in front of the screenings on Thursday evening, and it was a joy for all. Present, etc.

Louis Olivier

This presentation included, among other things, the film showing a moving locomotive;

5.At the Association Belge de Photographie, Brussels, 10 November 1895. This was the first presentation abroad;

6.At the Sorbonne in Paris, on November 16, 1895, at the opening of the courses of Messrs. Darboux, Troost, Lipmann and Bouty, in the presence of many scholars and personalities.

Once and for all, adding the dates of the first public and commercial screenings, marking the beginning of the film industry:

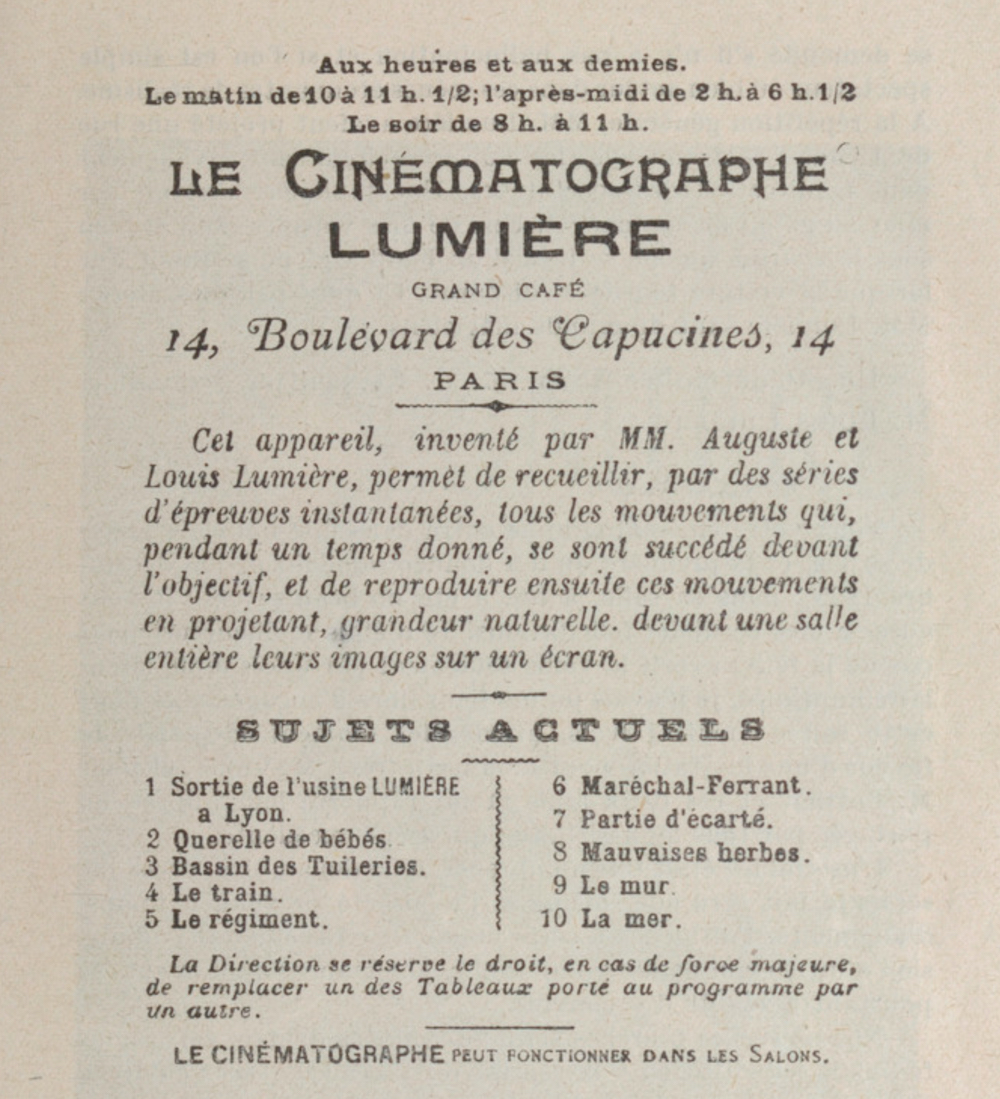

1. In Paris, in the basement of the Grand-Café, boulevard des Capucines 14, Saturday, December 28, 1895, and not on the 25th, as was often printed by mistake;

2.In Lyon, at no. 1 rue de la République, in a shop transformed into a theatre, on January 25, 1896, supervised by Mr. Perrigot, a close collaborator of the brothers Lumières;

3.In London, at the Polytechnic, February 17, 1896;

4.In Bordeaux, February 18, 1896;

5.In Brussels, 29 February 1896;

6.In Berlin, 30 April 1896;

7.In North America, May 1896.

[…]

At that time, the cinematographic strips, called “films” shortly afterwards, hardly exceeded seventeen meters; each screening consisted of only eight or ten different films; documentary scenes, germinal amusing scenarios, etc. The spectacle was permanent and took place in very cramped rooms arranged at random. Many astonished spectators believed it to be tricks, a kind of disappearing act, and could not explain this life so faithfully reproduced.

We will be allowed to insist on the first public film screening, the one that marks an almost solemn date; Mr. Clément Maurice as the concessionaire organized it. We must not forget the name of this pioneer. Thanks to Mr. C-L. Maurice Jr., today director of an important film printing house, we were able to gather useful information about this day and about his father who was the first cinematograph director.

The owner of the Grand-Café, on boulevard des Capucines, Mr Volpini, leased his basement for one year. He even refused 20% of the takings because he showed so little confidence in the success of the business and accepted a rental of thirty francs a day. Two posters were put up at the door and invitation cards were issued. Father Lumière had arranged everything and concerted with Mr. Clément Maurice.

The Christmas and New Year period had been chosen for the launch and the price of the tickets was set at one franc. The first day yielded 35 francs in takings.

The 16 to 17-metre-long films de résistance, which formed the core of the programme, were:

La sortie des ouvriers de l’usine Lumière;

Le goûter de bébé;

La pêche aux poissons rouges;

Le forgeron;

L’arrivée d’un train en gare;

La démolition d’un mur;

Soldats au manège;

M. Lumière et le jongleur Trewey jouant aux cartes;

La rue de la République à Lyon;

En mer par gros temps;

L’arroseur arrosé;

La destruction des mauvaises herbes.

The projection of 8 or 10 of these films lasted about twenty minutes. The room would be emptied, and once it was full again, it would start all over again.

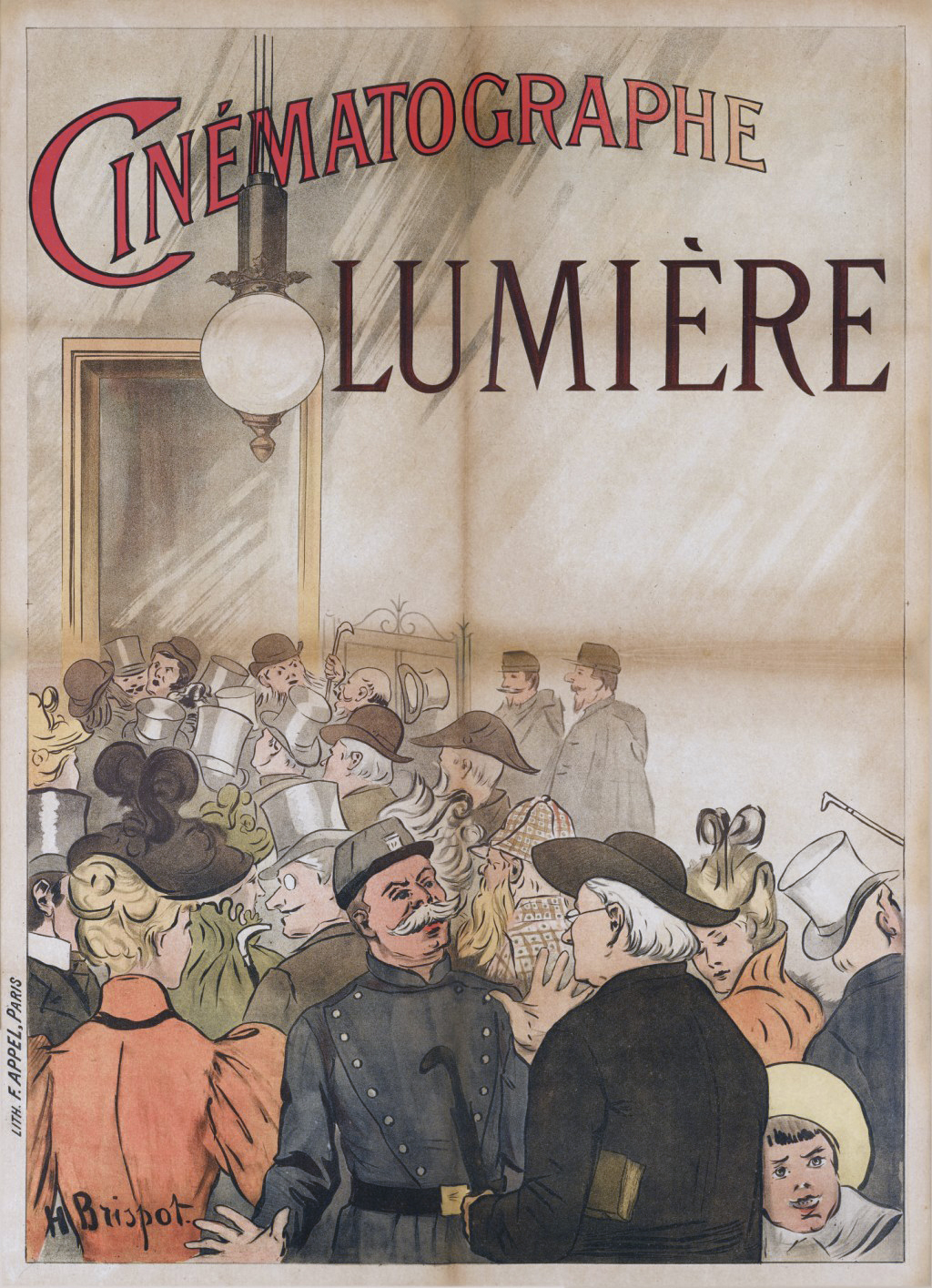

The success was so rapid that three weeks after the opening, the admissions were 2,000 and 2,500 a day, without any advertisements in the newspapers. Crowds queued and jostled, so much so that stewards had to oversee the place, as the hall could only hold 100 or 120 people at the most.

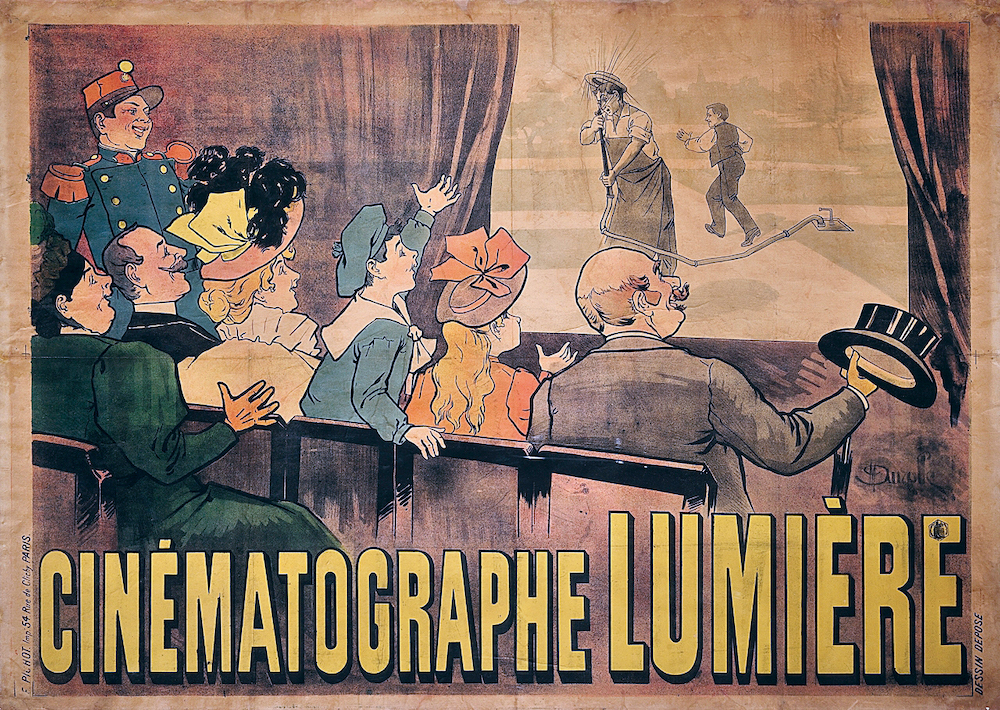

“My most typical memory,” says Mr. Clément Maurice, “is the face of the passer-by stopping in front of the entrance, wondering what Cinématographe Lumière could mean. Those who decided to enter came out a little bewildered; one could soon see them coming back, bringing with them all the people of acquaintance they had met on the boulevard. In the afternoon, the public formed a queue that often extended as far as the rue Caumartin. For several months, the program was hardly changed.”

Coming out of the first session, the scholar H. Parville recorded his impressions as follows:

“Its truth is unimaginable. The power of illusion! When you are in front of these moving tableaux, you wonder if it is not a hallucination and if you are just a spectator of or even an actor in these astonishing scenes of realism. At the general rehearsal, Mr Lumière had projected a street in Lyon. Tramways and cars were running, moving in the direction of spectators. An upholsterer came upon us at the gallop of her horse. One of my neighbours was so enchanted that she got up in a hurry... and did not sit down again until the carriage turned and disappeared. And we thought: Messrs. Lumière are great magicians.”

On December 30, 1895, Mr. J. Carpentier wrote to Mr. Louis Lumière:

My dear friend,

Your cinematograph has entered a new phase int its life, and the premiere on Saturday evening (December 28, 1895), in the hall devoted to it, was a great success; I offer you my cordial congratulations. Unfortunately I was not part of the party; warned the day before only by a simple printed circular, I had not been able to free myself of that evening’s commitments; but I had, at the last moment, asked the favour of an invitation for my brother-in-law, Mr. Violet, and for Mr. Cartier, and these two friends told me their impression, shared by all the assistants, which was excellent.

The assembly was very large. It must have been. So I would have been scrupulous, even if I had been warned in time, to increase the attendance at this premiere, by soliciting the admission of a certain number of friends and acquaintances whom I would have been pleased to invite...

Our new forks will be finished tomorrow evening; we will make the substitution at the resumption of the workshop work in 1896. This will be promptly removed and I will begin to ship the devices to you according to your orders.

Do we have the final type? Can we go ahead with the order of two hundred?

J. Carpentier

Also curious is the testimony of Mr. Georges Méliès, one of the veterans of cinema, director since 1888 of the Théâtre Robert-Houdin, a charming theatre where, two months after the appearance of the Lumière cinematograph, Kinetoscope films were screened, and where what has been called “les scènes à trucs” were to be born.

In 1895, on the floor above the Robert-Houdin theatre, Boulevard des Italiens 8, existed the old Disderi photo studio, then held by Emile Tourtin; Father Lumière came there frequently, having interests in this house which he supplied with photographic plates. I knew him because I met him often when I left my office. One evening, at about five o'clock, I saw him arrive, looking radiant, and he said to me:

- Are you free tonight?

- Yes, I replied, why?

- Come to the Grand-Café, at nine o’clock; you, who amaze everyone with your tricks, you’re going to see something that might amaze you yourself!

- Will I? What’s that?

- Shush, he replied, come and see, it’s worth it, but I don’t want to give any information about it.

Very intrigued, I accepted the invitation, and went to the Grand-Café at the appointed hour, having no idea what I was going to see.

The other guests and I were in the presence of a small screen, similar to the ones we used for the Molteni projections, and after a few moments a still photograph of Place Bellecour in Lyon appeared in projection. A little surprised, I barely had time to say to my neighbour:

“Is it to show us projections that we are disturbed? I’ve been making them for more than ten years.”

I was just finishing my sentence, when a horse dragging a truck started moving towards us, followed by other cars, then by passers-by, in a word, all the activity of the street. At this spectacle we all remained speechless, stunned, surprised beyond all expression. Subsequently were shown:

Le mur s’abattant sous la pioche des démolisseurs dans un nuage de poussière; L’arrivée d’un train; Le bébé mangeant sa soupe, with (as backdrop) des arbres dont les feuilles remuaient au vent; then La sortie des ouvriers de la maison Lumière; finally the famous Arroseur arrosé.

At the end of the presentation, it was a delirium, and everyone was wondering how they could have achieved such a result.

At the end of the screening, I was making offers to Mr. Lumière to buy one of his devices for my theatre. He refused. However, I had gone as high as 10,000 francs, which seemed to me an enormous sum. Mr. Thomas, director of the Grévin museum, having the same idea, offered him 20,000 francs, without any further result. Finally, Mr. Lallemand, director of the Folies Bergères, who was also present, offered 50,000 francs. It was a lost cause. Mr. Lumière remained uncompromising and answered with kindness:

“This device is a great secret, and I don’t want to sell it; I want to exploit it myself and exclusively.”

We left, delighted on the one hand, but on the other hand very disappointed and dissatisfied, because we had immediately understood the immense monetary success that this discovery was going to have.

Before this memorable session, there was only the Edison Kinetoscope (direct view of the moving film through a magnifying lens) and the small notebooks that were leafed through by hand, representing boxers, fencers, a dancer in motion. But nowhere any projection was taking place. So it was Lumière who first projected animated films and made them a public spectacle.

Edison was also working on a projector, but his apparatus came out long after Lumière’s; like ours, by the way, and like those of W. Paul in England.

We have mentioned above, among the Lumière cinematograph concessionaires, Mr. Félicien Trewey, a great friend of father Lumière, and a famous magician, who lived in Villa de la Lune in Asnières. He had the honour to give the first demonstrations of this apparatus in London: on 7 February 1896, at the Empire theatre, a session reserved exclusively for the press; on the 17th of the same month, a public session at Polytechnic; on 11 March 1896, a private session organised at Polytechnic, for H.R.H. the Duke of Connaught, accompanied by five people.

While Mr. Trewey was providing fame for the brothers Lumière in Great Britain, other agents, collaborators or concessionaires were organizing screenings that were no less successful.

In April 1896, in Vienna, Emperor Franz Joseph, intrigued by what he was told, visited the cinema, applauded frantically and, through his agent, Mr. Promio, wished to offer his warmest congratulations to the inventors.

On June 12, 1896, Her Majesty the Queen of Spain did the same, as did the King of Serbia on the 25th of the same month.

On July 7 and 21, 1896, two benevolent sessions were held at Peterhof, St. Petersburg, under the chairmanship of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, Their Majesties and the entire court; congratulations were again extended to Messrs. Lumière.

In August 1896, it was the King of Romania’s turn.

This explains how, in the course of 1896, the Lumière cinematograph made a prodigiously successful tour of Europe.

We are not unaware of the fact that a competition quickly established itself, sometimes creating confusion and errors, which the Lumière brothers did not consider useful to rectify, for the sole reason that they could not meet all the demands.

In January 1896, for example, an English device, the Bioscope, made its debut in Paris, and at the end of November of the same year the American Biograph, projecting forty-metre strips, was installed at the Folies Bergères.

[…]

At the 1900 World’s Fair, the Lumière brothers decided to attract the attention of the crowd and designed a great installation for the time.

The screen, equipped by Mr. Lachambre, a balloon builder, was installed under the arch of the Galerie des Machines; it was 21 meters long and 15 meters high: twenty-five thousand spectators could watch the animated projections. A 120-150-amp marine projector was used as a light source. One could watch both sides of the screen, which was wetted to obtain a good transparency without light points.

During the day, this gigantic screen remained immersed in a tank full of water, covered by a double set of trapdoors; in the evening, two winches, located under the dome, pulled it back into place.

There was talk of outdoor projections, with this really imposing material of such dimensions.

“A large-scale experiment, attempted at the Champ-de-Mars, under the Eiffel Tower,” said Mr. Louis Lumière, “showed me that it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to use a large screen in the open air, because of the movements of the air which, according to the statistics I had been studying at the time, had shown me that it would hardly be possible to operate five or six times during the 1900 Exposition. The experience was unfortunate, moreover, and had no sequel.”

[…]

Such were the beginnings of the cinematograph, baptized by the Lumière brothers, as early as 1895. The Lumière brothers recognized, moreover, that they adopted this name without knowing the February 12, 1892 patent of Léon Bouly, which we have mentioned before.

“We believed to be the first to invent the term cinematograph” wrote Mr. Louis Lumière, “and we learned only later that Mr. Léon Bouly had created it to designate a device that never saw the light of day, because it could not lead to the practical solution of the problem.”

In the same letter, in spite of the above-mentioned statements of Mr. Auguste Lumière, his brother Louis expresses the desire that both remain united in the history of the cinematograph. This is all the more right as, after having discovered the treasure together, they wanted to deposit it together at the feet of science. And, besides, there is not a Frenchman who, in his admiration and gratitude, does not confuse Auguste with Louis Lumière.

-------

La sortie de l’usine Lumière à Lyon (Auguste & Louis Lumière, 1895)

L’arroseur arrosé (Auguste & Louis Lumière, 1895)

These excerpts were originally published in: Georges-Michel Coissac, Histoire du cinématographe: de ses origines à nos jours (Paris: Éditions du Cinéopse, 1925).