The Materialist

William Friedkin (1935-2023)

I sometimes think that if I were able to write about everything I wanted, my work would turn into an altar of the dead. Every other week, it seems, some film artist I care deeply about passes away (I still hope to write something about Jacques Rozier for instance), and a cinema I’m very emotionally involved in appears to be reaching its natural end (when it’s not already mostly forgotten by the powers that be outside late-career homages). This is all to say that William Friedkin passed away on August 7, and I’ve obsessed and written about his films a lot through the years. Friedkin left a new posthumous film which just had its debut at the Venice Film Festival, a new adaptation of Herman Woulk’s The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial, his first fictional movie in over a decade. But while new work didn’t come often late in his life, he has been very present over the past few years. He wrote an autobiography, The Friedkin Connection, that will rightly live on as part of the canon of filmmaker tell-alls; he received multiple homages and gave numerous masterclasses; and he was very active on social media. The aging Friedkin loved to talk about himself, and people do love an old guy who is so blunt with his own brand of truth. It’s the kind of late career that happens for too many major artists, even more so when they are the kind of insider-outsider maverick that Friedkin represented so well. Listening to Friedkin talk is great fun (I’m still disappointed an ear infection made him cancel a trip to São Paulo in 2016), but I wish we paid homage to Friedkin by allowing him to make another two or three features, even if it turns out I didn’t like them much at our first meeting.

I sometimes think that if I were able to write about everything I wanted, my work would turn into an altar of the dead. Every other week, it seems, some film artist I care deeply about passes away (I still hope to write something about Jacques Rozier for instance), and a cinema I’m very emotionally involved in appears to be reaching its natural end (when it’s not already mostly forgotten by the powers that be outside late-career homages). This is all to say that William Friedkin passed away on August 7, and I’ve obsessed and written about his films a lot through the years. Friedkin left a new posthumous film which just had its debut at the Venice Film Festival, a new adaptation of Herman Woulk’s The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial, his first fictional movie in over a decade. But while new work didn’t come often late in his life, he has been very present over the past few years. He wrote an autobiography, The Friedkin Connection, that will rightly live on as part of the canon of filmmaker tell-alls; he received multiple homages and gave numerous masterclasses; and he was very active on social media. The aging Friedkin loved to talk about himself, and people do love an old guy who is so blunt with his own brand of truth. It’s the kind of late career that happens for too many major artists, even more so when they are the kind of insider-outsider maverick that Friedkin represented so well. Listening to Friedkin talk is great fun (I’m still disappointed an ear infection made him cancel a trip to São Paulo in 2016), but I wish we paid homage to Friedkin by allowing him to make another two or three features, even if it turns out I didn’t like them much at our first meeting.

Friedkin’s position does add certain peculiarities. Film history is often written by the survivors and victors, but when it comes to Hollywood history, and for some reason the history of the 1970s in particular, it has often been written by those in the film industry itself. There’s a reason Peter Biskind’s gossipy Easy Riders, Raging Bulls has far too often become the final judgement on the subject, and it’s almost never taken into account how every stupid aesthetic judgment in it comes from the author being a failed executive. Quite a few Friedkin flops have been recuperated among film enthusiasts (I’m very glad his film maudit masterpiece Sorcerer [1977] has enjoyed a new life since its 2013 restoration), but the stink of failure and the idea that his filmography boils down to his two major early 1970s hits, The French Connection (1971) and The Exorcist (1973), and everything else can still be discounted as curiosity if not pure shame still shows up far too often in more mainstream appraisals, as one can notice looking at some of the obituaries that have appeared since his passing. Of course, being known as “the director of The Exorcist” has its advantages, and Friedkin himself took advantage of that by remaining involved in later releases and, more recently, making a not-good documentary about a real-life exorcist called The Devil and Father Amorth (2017). It’s hard to deny that he deserves better than the moniker, and when he gets reduced to that in death, film culture is failing him yet again.

The Exorcist is a pretty good film, but it’s not quite one of my favorites. Friedkin is still the rare filmmaker whose best work is usually among the films people are more likely to have seen: The French Connection, Sorcerer, Cruising (1980), and To Live and Die in L.A. (1985). Those five films by themselves make for quite a filmography, at the same time very exciting and upsetting, but there are a few worthwhile hidden gems: a couple from late in his career, The Hunted (2003) and Bug (2006); the very amiable heist comedy The Brink’s Job (1978); the messy but likable period piece The Night They Raided Minsky’s (1968); and his debut TV documentary about a death row inmate, The People vs. Paul Crump (1962). His filmography certainly has its unevenness – he couldn’t always salvage bad projects. His first Hollywood movie, Good Times (1967), has some charm, but there’s nothing he could do to make up for Sonny Bono, unlike Cher, not being made for the movies. One sometimes suspects he might not have tried very hard, and the less said about his Chevy Chase comedy Deal of the Century (1983) the better.

After The French Connection made him famous, Friedkin mostly committed himself to pulp movies, crime and horror in general, sometimes even blending them together. Cruising, for example, often feels like a possession film. As a formalist, those films more than offered him opportunity for exploration, but he was also always attracted to stage or stage-bound material that often gave him plenty of room to explore his formal control of tight screen spaces. He went to England to make a decent Harold Pinter adaptation, The Birthday Party (1968), and he was responsible for the film version of Matt Crowley’s The Boys in the Band (1970) with the original cast. By the late 1990s he did a much better than necessary fortieth anniversary version of 12 Angry Men (1997) for TNT and two Tracey Letts adaptations, the already mentioned Bug and Killer Joe (2011). Those films mostly take place in enclosed spaces and make great use of Friedkin’s fluid camera and editing instincts; they are usually tense and organized in a thriller manner. I can only assume the self-loathing barbs of The Boys in the Band play a little less punishing when the cast is allowed to share a stage, but they have a memorable, cutting quality as Friedkin breaks down their room through his blocking and editing. I haven’t seen it yet but considering the nature of the material I assume The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial probably follows a similar path.

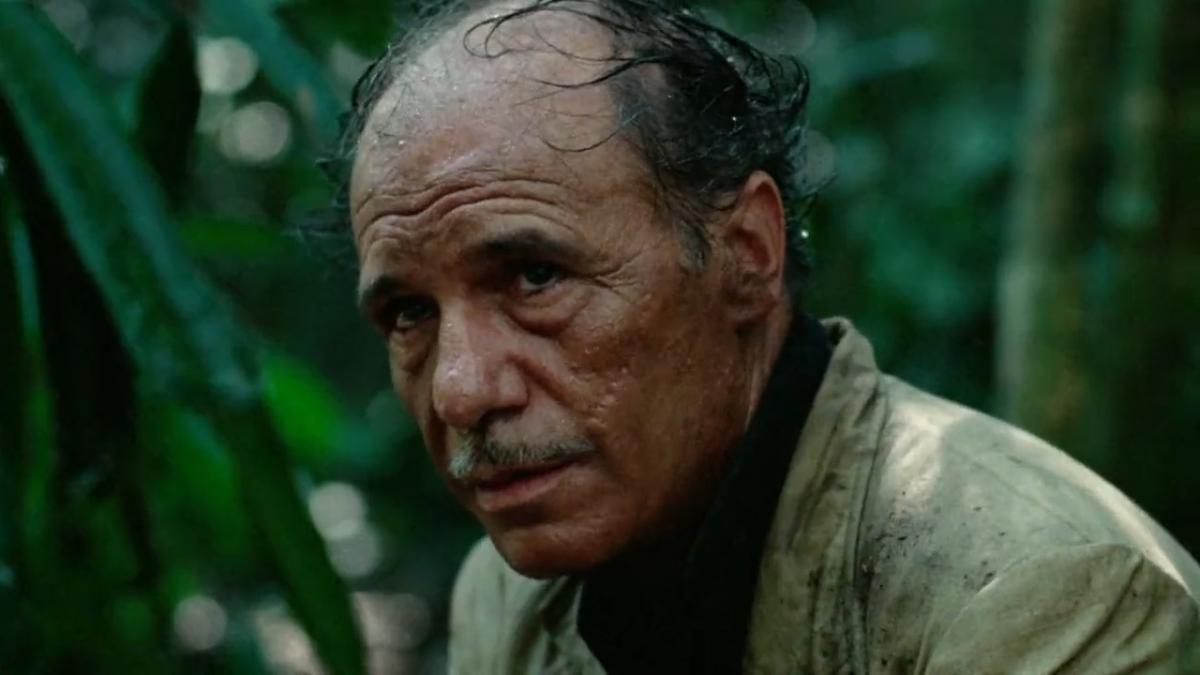

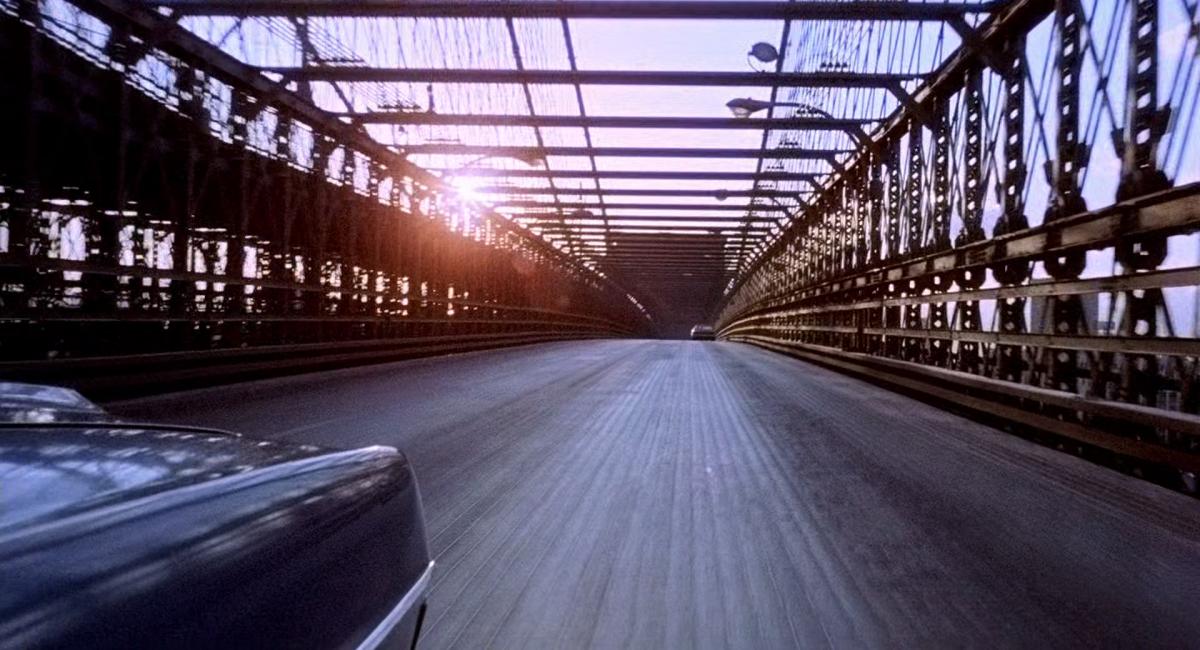

Friedkin’s work combines a facility with location shooting, a desire to include as much researched material to anchor the drama as possible, and editing instincts that punch up and distort the action. It’s a very sensationalist approach built on a documentary-like foundation. All this pays off spectacularly in The French Connection, a film whose popularity was based on an incredible car chase that came from the observation that he could get a car to follow a train in the streets of New York. There are many commendable things about The French Connection, but it’s above all a triumph of well-chosen, very downbeat locations. I’ve always been partial to this description from Kent Jones 2005 appraisal of the filmmaker: “Like Abel Ferrara, Friedkin only makes movies in places Woody Allen would never dream of visiting”. Indeed, there’s something thoroughly unglamorized about Friedkin’s cinema – his sets are very beat down, rarely upscale and his actors all seem like they do some physical work for a living. His one major film with a clearer middle-class subject, The Exorcist, is about the invasion of its space by forces impossible to put into words. Friedkin was great with faces – few things are as powerful on film as a Francisco Rabal closeup in Sorcerer) and while drama was never a major concern, he is great at work with actors so action and character can go together. Hackman’s Popeye Doyle is probably the better example of this, but there’s many others like Michael Shannon in Bug or Bruno Cramer in Sorcerer. He was also great with typecasting, knowing exactly when a look and posture would be all the characterization needed as one can notice on Eurocrime vet Marcel Bozzuffi in The French Connection or his exploration of young Willem Dafoe’s empty face on To Live and Die in L.A..

His sensationalism was based on the desire to get a reaction. One of the most memorable violent screenings I can remember was the first time I saw Bug. The Brazilian distributor released it under the very silly title Possessed and dumped it only on malls in more working-class areas, so there I went to catch it on a Sunday afternoon in a theater full of teenagers and couples ready to watch a horror movie “from the director of The Exorcist”. It was a predictable disaster, the contentious atmosphere as palpable as the movie’s malaise. Somehow I suspect Friedkin would approve, a strong reaction, even a negative one beats a dead theater. By the same token few were as good at sudden explosions of violence, there’s an out of nowhere shot to the face in To Live and Die in L.A. that no one who saw it ever forgets.

The filmmaker was often very friendly with cops, and he would bring plenty of his first-hand experience with them as documentary detail in his movies. There’s a moment in Cruising when a gay suspect is brought in and this Black man looking like a complete made up apparition is sent to the room to beat him up. It’s an absurd moment that seems out of pure Hollywood delirium, but it turns out actual cops told Friedkin about how they would bring this man to torture gay suspects under the certainty that when they scream police brutality, no one would believe their description. The French Connection and Cruising, are, whatever else one might think about them, shockingly blunt movies about police racism and homophobia.

Friedkin’s more progressive defenders like to cite his portrayal of law enforcement to beef up his political credentials, but I’d say it’s more a matter of honesty; he filmed what he knows and has seen, and it’s just hardly ever positive. The fact remains that Friedkin films do include some of the least positive images of police in Hollywood cinema. William Petersen’s federal agent in To Live and Die in L.A. might be the most inept cop in all American movies, doing barely a thing to catch the counterfeiter he is after but leaving an unbelievable trail of emotional and physical collateral damage in his wake. That his movies do this from a position of intimacy adds to a damming image. Back in 1971, plenty of ink was used to compare The French Connection and Dirty Harry. The two films are very similar in their tales of obsession, excuses for power abuse, and use of location. By eliminating some more recognizable liberal signposts, Friedkin’s film probably makes its Nixonian law and order ethos easier to take (Pauline Kael famous takedown of Dirty Harry often feels written in defense of all the lawyers who read The New Yorker; no such necessity here), but The French Connection is less taken by identification shortcuts, and its final movement towards moral bleakness is more radical. It’s a void, regardless of where one stands ideologically.

The truth is that there are fewer big misanthropes in film than Friedkin. He just rarely seems to have a decent opinion of other human beings, not that he is especially nicer about himself: his autobiography starts in a self-defeating manner, listing a series of personal mistakes, beginning with the tale of how a young Jean-Michel Basquiat gifted him a painting he promptly threw in the trash because, well, he wasted so much money that day. One suspects the reason he loved staging car chases was because it allowed him to completely downplay the human element. Machines in the environment might be the ideal form for Friedkin’s worldview. The Exorcist’s popularity is tied to how it treats its theology seriously, while suggesting a hardly reassuring view of faith. Cruising’s unpopularity and later reappraisal have a lot to do with how it ties desire and violence together. It’s certainly very much a straight man’s view of gay culture, but its later popularity among queer people too young to deal with its polemical reception at the time, both as a document of a scene that would be completely changed by AIDS not long after and as a look at desire, does attest to some of its power. It’s a movie that has aged well precisely because it’s not of our time, so both its blunders and merits can be observed with different eyes.

Among many things, Friedkin’s career is an impressive example of perseverance and survival instincts – one of the reasons reducing him to his early two hits feels so wrong. Yesterday I saw a writer talking about how, when in film school, he went to a Friedkin masterclass and how he pissed off young students by talking about how film directing was mostly about learning how to take shit from all parties. Friedkin certainly knew how to take shit and sometimes, let’s be fair, just throw it back on screen. Almost everything In To Live and Die in L.A., a film shot on the periphery of the film industry, comes from this idea of forgery, it’s a complete inversion of The French Connection, with New Hollywood giving away to the artificial, synthetic 1980s and the filmmaker seeking ways to make some of his same aesthetic strengths matter in a radical different context. It even has its own great chase scene, and it’s every bit as big a triumph and arguably a more deeply felt one. The villain is a literal counterfeit artist, postmodern painter by day, forger by night. In retrospect, Friedkin’s counterfeit image feels prophetic, as time passes and the existence of the artist in commercial American cinema seems more and more dependent on then disappearing into money.

By the early 1990s, most of Friedkin’s contemporaries were slowing down and complaining plenty about the new realities of film production. As it so happens, his wife, the producer Sherry Lensing, became at the time head of Paramount, and the filmmaker rode the personal action to a second wind as an almost anonymous Hollywood journeyman, using his many formal skills to adorn a series of disposable thrillers. The quality of Friedkin’s films during his decade working for Paramount varies heavily; he couldn’t do much to elevate Joe Eszterhas’s god-awful script for Jade (1995), for instance. One of his last films for the studio was the rather vile military courtroom drama Rules of Engagement (2000). One of the downsides of Friedkin’s sensationalism is a weakness for cheap provocative material, and no more so than in this film about American military violence abroad, an easy excuse for any sort of imperialist violence. Even there, the film is blocked with a level of care this kind of studio product never achieved by 2000, and the courtroom scenes do not have a shot that does not feel ideally framed and cut. If the formalism redeems the material or makes it more offensive, it’s up to the audience. The Paramount period, and the end of his Hollywood career, came to an end in 2003 with The Hunted (2003), arguably his best film since To Live and Die in L.A. and the purest expression of his filmmaking ideas since Sorcerer: one man pursuing the other through the woods, and it’s all down to how well either can understand the landscape as the images give to brutal sensation.

Friedkin’s cinema is always tied to this idea of the environment. He is a filmmaker who believes in the medium’s materialism and the different ways it can express ideas and emotions. One of the things that stand out about Bug is its dedication to two damaged people whose emotional disappointments are given physical manifestation. It’s an acute look at how life can be distorted in the face of personal-made fictions, and as the critic Adam Nayman observed, it feels way ahead of the curve as a representation of some forms of collective fiction to replace private lives’ hardships. At the opposite extreme of his career, The People vs. Paul Crump is exemplary. A mix of direct cinema and reenactments made on behalf of a Black man who was waiting execution for murdering a security guard a decade earlier. Friedkin believes in Crump’s innocence, but that is secondary to the film he is making; as his lawyer articulates later in it, “the state should not be premeditating murdering anybody.” Everything else comes after this realization, and the film’s articulation that an immersion on Crump’s being would be enough to convince anyone of it. The film was never shown on TV, too polemical, but it fulfilled its intentions: the governor watched it, and the cinema did what the lawyers failed, he didn’t get convinced of Crump’s innocence, but he did come out believing he was a reformed man, so he suspended the death sentence.

All this approach pays off splendidly in Sorcerer, the movie Friedkin used his newfound Exorcist power to make. A big production shot on location mostly in the Dominican Republic, it’s a remake of Henri Georges Clozout’s classic French thriller The Wages of Fear. Four men have to drive two trucks full of highly volatile material through a very dangerous natural road. The film is completely taken over by the place, and the characters’ task and the filmmakers become one and the same. Action filmmaking as a process, that erases the distance between the physical dimension and the screen experience. Clozout’s original is a very well put together movie and very thrilling; it’s a film made from up to down, the drama of social need is set up and executed skillfully as narrative cinema; we remember the general design of the drama, the motivations behind it, and the carefully arrived payoffs. By contrast, Sorcerer is a materialist nightmare; what remains are faces, the road, nature, and the weather. It seems like an impossible and dangerous activity on and outside the screen, and this literal dimension is what hits hard.

There’s nothing great about Sorcerer that could be described in literate terms. It’s an awe of madness and physical detail. An incredibly bleak movie, it shifts the motivations, so it’s a tale of four foreign men who put themselves in a third-world purgatory, running from their past but above all as self-punishment. The road becomes an exercise in masochism; these men are driving towards death, and it’s equated with them disappearing into the movie itself. Clozout’s movie deals with psychology, which is always more fashionable, but Friedkin’s reduces the men to a series of actions and gestures (the actors – Roy Scheider, Francisco Rabal, Bruno Kramer, and Amidou – are all remarkable). The film starts with a series of action scenes shot around the world that less set up characters than introduce a formal principle, like they are all being guided by Friedkin’s editing towards the dangerous journey, and it reaches a peak when they have to cross a very frail bridge, a vision of filmmaking, of a creation of a world married into the exquisite formal execution of one dangerous task.

Sorcerer was, of course, a major flop and one of the big films that ended New Hollywood. It languished forgotten by the snobs (how can it compare to a European classic!) and by the industry populist types (who wants cinema to be the space of mad men wasting money in crazy personal endeavors?). A few people like it very much, but until the recent restoration kicked off a larger reappraisal it was a specialty taste. Even people who don’t particularly love it get impressed by its sheer ambition. Back in 2016, there was a Friedkin homage as part of the São Paulo Film Festival and I got to watch Sorcerer and To Live and Die in L.A. in a double bill in the best local art house theater, and it was one of the best “cinema can do this” moments I had in the last decade. Is Sorcerer a road not taken in popular cinema? Perhaps, for a while before it, Friedkin was partners with Francis Ford Coppola and Peter Bogdanovich in a production company called the Director’s Company, which, as the name suggests, aimed to put artistic independence as its prime interest. It was responsible for Bogdanovich’s Paper Moon (1973) and Daisy Miller (1974), and Coppola’s The Conversation (1974) and folded after the second Bogdanovich film flopped. A film like Sorcerer (or The Conversation for that matter) points towards a desire to marry very personal sensibilities, populist narratives, and the kind of film machinery only large amounts of money can buy. We didn’t see things like it quite as often in the past as nostalgia suggests, but we do see it even less now. The film industry is a very cruel thing, and how it likes to perceive itself often changes on a whim of not always readable self-interests. Friedkin was a weird artier young filmmaker and then he was a hotshot maverick, an embarrassing failure, an anonymous journeyman and finally a master better seen in the safe confines of the past. He certainly had a healthier and much longer career than many similarly talented people, but like a lot of other great filmmakers, he should be seen as vital and often is not. Sorcerer’s mix of arrogance and skill is not something to be written off easily, and a lot of Friedkin’s reports from a nihilist place remain very alive.

Image (1) from The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973)

Images (2) and (4) from Sorcerer (William Friedkin, 1977)

Image (3) from The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971)

A version of this text was originally published on Anotacões de um Cinéfilo, 8 August 2023.