Like Columbus who discovered America and changed the course of history, the ‘other Christopher Columbus’, Cristóbal, a shipwrecked mariner from the Mediterranean, discovered America anew in twentieth-century Cuba, where the course of history was again to be changed.

“When I studied, I met a filmmaker who decided for me, in a way, what I was going to become. It was Armand Gatti who brought us together.”

Jean-Pierre Dardenne1

« Le cinéma, c’est un système qui permet à Godard d’être romancier, à Armand Gatti de faire du théâtre et à moi des essais. »

“Film is a system that allows Godard to be a novelist, Armand Gatti to make theater, and me to make essays.”

Chris Marker2

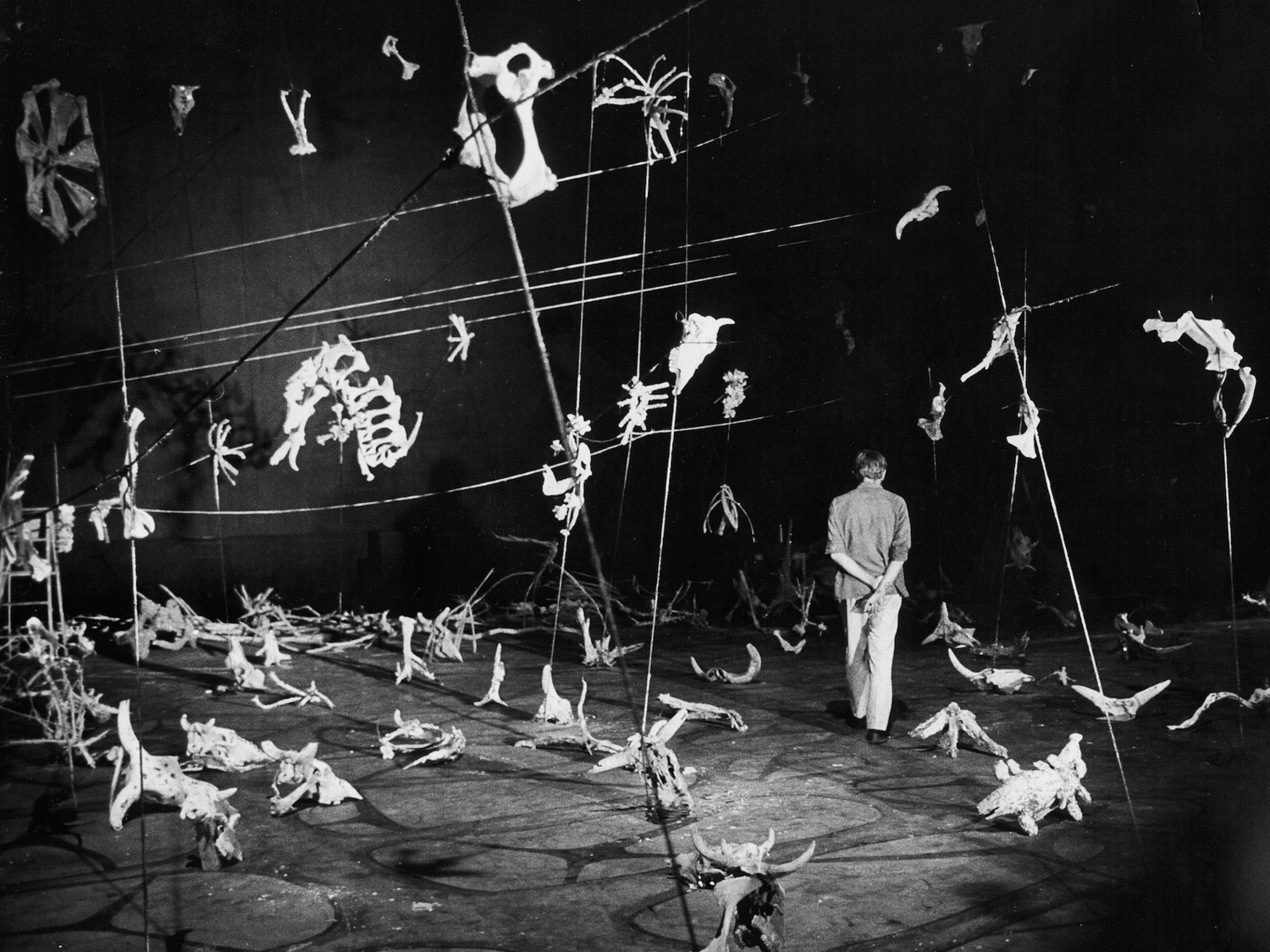

« El otro Cristóbal est un film injustement méconnu, à la genèse complexe. Après une première expérience remarquée en tant que cinéaste (L’Enclos, 1960), Gatti est invité par Fidel Castro, sur une recommandation de Joris Ivens et de Che Guevara (rencontré en 1954 lors d’un reportage sur la guerre civile au Guatemala), afin de réaliser un film qui doit représenter Cuba au Festival de Cannes en 1963. Le tournage se déroule à partir de novembre 1962, en pleine Crise des missiles, alors que l’île est depuis peu soumise à un blocus qui transforme le moindre problème technique ou matériel en difficulté insurmontable.

Cristóbal manifeste le souci d’une intervention engagée, mais aussi le désir de la part de l’auteur de préserver son intégrité intellectuelle, morale et politique, ainsi que son imaginaire propre. Les films étrangers réalisés à Cuba sont généralement des documentaires militants (e.g. Joris Ivens) ou subjectifs: les « points de vue documentés », selon une expression de Jean Vigo revendiquée par Chris Marker (Cuba Si !,1961) et Agnès Varda (Salut les Cubains, 1962). Quant à Soy Cuba du cinéaste soviétique Mikhaïl Kalatozov, il relève de la fiction historique et se caractérise par la convocation d’événements historiquement attestés par le biais de personnages imaginaires.

D’emblée, Gatti prend un chemin singulier : Cristóbal apparaît comme une allégorie politique dont le sens reste ouvert : que devient la réalité politique quand elle est vue à travers le prisme d’une fiction qui se développe sur le registre du merveilleux ?

La convocation de l’exubérance créole (ironie, danse, laisser-aller, sentiment du tragique, pensée magique) pour retracer un moment de l’Histoire révolutionnaire fait l’admiration des cinéastes brésiliens du cinema novo : l’influence de Cristóbal est sensible en particulier dans Terre en transe de Glauber Rocha en 1967. On y retrouve la manifestation-carnaval, la richesse des costumes et des décors, les symboles divins, ou encore la liaison entre religion et révolution. Les plans séquence en caméra portée dans la foule apparaissent aussi comme une réminiscence des mouvements d’appareil complexes de Cristóbal. Cette esthétique semble également avoir marqué Soy Cuba de Kalatozov. »

Sylvain Dreyer3

« On a dit que El Otro Cristóbal était un film délirant. C’est une facilité ! Je préfère traduire délire par liberté, une très grande liberté, la possibilité de libérer toute une série de concepts, d’images, de façons d’être. Lorsque quelque chose se libère, on parle de délire, au sens où le mot devient une forme de censure. Devant une telle tentative, on se dit attention, voilà un torrent, construisons vite une digue, alors on recourt aux mots passe-partout du genre délire et tout rentre dans l’ordre. »

Armand Gatti4

« Comment trouver une écriture qui parle le langage de cette révolution que nous voyons en train de se faire avec tous ses mythes, ses exagérations, avec ses drames, et avoir cette espèce de souffle, de ton d’épopée qui nous paraissait être le seul convenant, ayant rapport avec la révolution ? Ça a été le point de départ. Le titre du film traduit veut dire ‘L’autre Christophe Colomb’. Ça se situe directement dans ce monde des libérations, on va vers les Amériques de nouveau, on s’arrête là-bas et on essaie de vivre cette Amérique en tant qu’utopie, et dans un sens, le fait que ce fut l’Amérique, l’endroit de découverte de Christophe Colomb, que ce fut également une révolution, c’était une espèce de triple existence d’une même utopie, à l’intérieur d’une même aventure qui, à ce moment-là, nous séduisait beaucoup. »

Armand Gatti5

“Gatti’s problem was to create a form of film which ‘spoke the language of the Revolution’ that was taking place under his eyes, together with all its drama and myths. This vast cinematographic poem contains a wealth of visual imagery from Caribbean folklore and also from Christian mythology and literature. The positioning of the camera is often striking. Gatti does not admit of an art which is revolutionary in intent without being revolutionary in form. Bourgeois aesthetic norms have to be abandoned, or they end by stifling the revolutionary idea. With this film Gatti aimed at developing an aesthetics in keeping with his theme and as a source of inventiveness and poetry.

The basic principle in making the film was collective responsibility with people of French, Cuban and other nationalities all working together as if they belonged to the same country despite language barriers. All freely took on the necessary tasks. While playing Cristobal Jean Bouise was also assistant stage designer and wardrobe keeper. Adouardo Manet, who directed some of the shooting, became the back legs of the ‘horse’ in the bullfight, and also worked the ‘snow pistol’. People whom Gatti had looked upon at first as executants became creators in their own right. This, Gatti felt, was a real triumph.

For Gatti's French assistant Jean Michaud, the allusion to Columbus stopped at the ‘discovery’. Not so for the Cubans: they saw in the ‘other Cristobal’ a reflection of Henri Christophe, the freed slave who had championed the cause of his fellow-men in Haiti a century and a half before.

At the Cannes Film Festival, the press was divided. The Right was hostile, the Left was favourable – both for equally wrong reasons, as Gatti put it.”

Dorothy Knowles6

One of the most acclaimed theater writer-directors of the 20th century, Armand Gatti (born Dante Sauveur Gatti) was originally a member of the informal Left Bank group of filmmakers that included Alain Resnais, Chris Marker and Agnès Varda, but remains an elusive figure for many. He was born in 1924 in a shantytown in Monaco to a maid and an Italian anarchist from Piedmont, who escaped murder in a Chicago slaughterhouse because of his political activities and fled Benito Mussolini’s regime. During World War II, Gatti joined a small French resistance maquis. Captured, tortured, and sentenced to a concentration camp in Hamburg where he was forced to work in a diving bell at the bottom of the Baltic Sea, he eventually escaped and joined a British Special Air Service special forces team. After the war, he worked as an award-winning journalist for many years until he traveled with Chris Marker, published his first plays, and directed his first film, L’Enclos (1961). He was awarded the French Legion of Honour in 1999, the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 2004 and the Grand prix du théâtre from the Académie française in 2013. He died on April 6, 2017.

- 1Jean-Pierre Dardenne, Cannes masterclass, 2009.

- 2Entretien avec Chris Marker par Jean-Louis Pays, Miroir du cinéma, n°2, mai 1962, 4-7.

- 3Sylvain Dreyer, “El Otro Cristóbal, les hommes à la conquête du ciel,” Cahiers Armand Gatti, n°2, 2011.

- 4Entretien avec Armand Gatti par Jean Bouise, Michaud et Hubert Montloup, “Nous Vaincrons: Table-ronde avec la ‘brigade Cristobal,’” Miroir du cinéma, n°6/7, 1963.

- 5Armand Gatti, “Interviews cinématographiques illustrés,” Dans: Michel Séonnet et Armand Gatti, Gatti : Journal illustré d’une écriture (Montreuil: Artefact, 1987).

- 6Dorothy Knowles, “The Caribbean: Aggression and Resistance: El Otro Cristobal. Notre tranchée de chaque jour,” Armand Gatti in the Theatre: Wild Duck Against the Wind (London: Athlone Press, 1989), 95-98.