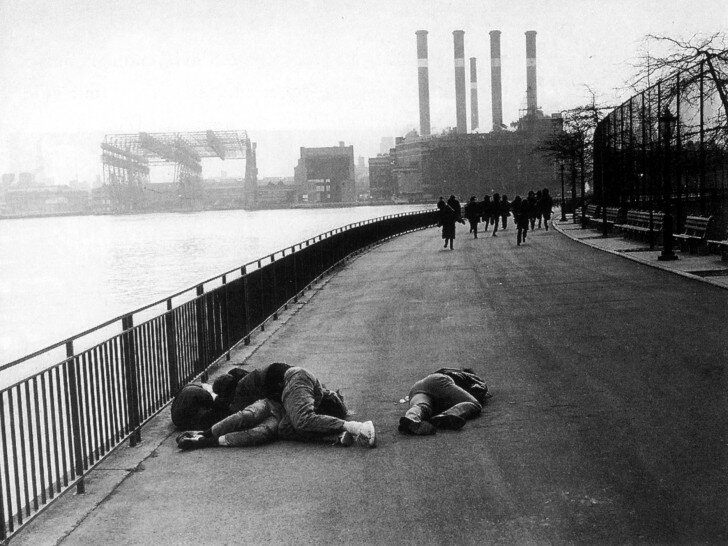

An underground revolutionary group struggles against internal strife to stage urban guerilla attacks against a fictionalized fascist regime in the United States. Interspersed throughout the narrative are rhetorical sequences that explain the philosophy of radical action and restrain the melodrama inherent in the thriller genre.

EN

“One of American independent Robert Kramer’s strongest ‘underground’ features (1969), arguably his best, made in and around New York before he resettled in Paris. This potent and grim SF thriller about urban guerrillas of the radical left, shot in the manner of a rough documentary in black and white, has an epic sweep to it. (Like many politically informed art movies of the period, starting with Alphaville and including even THX 1138, it was set in the future mainly as a ruse for critiquing the present.) Now as then, the power of this creepy movie rests largely in its dead-on critique of the paranoia and internecine battles that characterized revolutionary politics during the 60s; the mood is terrorized and often brutal, but the behavioral observations and some of the tenderness periodically call to mind early Cassavetes. A searing, unnerving history lesson, it’s an American counterpart to some of Jacques Rivette’s conspiracy pictures, a desperate message found in a bottle.”

Jonathan Rosenbaum1

“Ice wasn’t a thesis in favor of armed struggle. It was trying to explain why those people felt that way, the rage they felt, and the consequences of that rage in their lives, understood as something quite negative, indeed as their self-destruction… and however, it was still preferable to daily life in America."

Robert Kramer2

“Ice (1969), a two-and-a-half-hour movie which is still around and being shown, cost $13,000. Everybody who worked on that film worked on it for nothing. That changed everything about working on the film because it's absolutely impossible to say to somebody who believes that their point of view is precious enough to go to jail for, ‘Say those lines because I tell you to say those lines.’ They’re going to say, ‘I’m not going to say those lines. I don’t believe in that.’ And you’re instantly into a very interesting thing which has not stopped at all. I would say, ‘Well, that’s okay, but it’s not good for the character. What about this?’ And then they say, ‘Well, I could accept this part if I don’t have to say that part.’ I like this negotiation and it blurs even more the line between documentary and fiction because what you’re actually dealing with is the life of people who are in the movie. This is as true of Walk the Walk now as it was for films made during the sixties and seventies.”

Robert Kramer3

- 1Jonathan Rosenbaum, “Ice,” The Chicago Reader, 1985.

- 2Serge Toubiana, Annie Cot, Marthe Cartier-Bresson, "Entretien avec Robert Kramer," Cahiers du cinéma, no. 295 (1978).

- 3“A Discussion with Frederick Wiseman and Robert Kramer,” Dérives.tv, 1997.