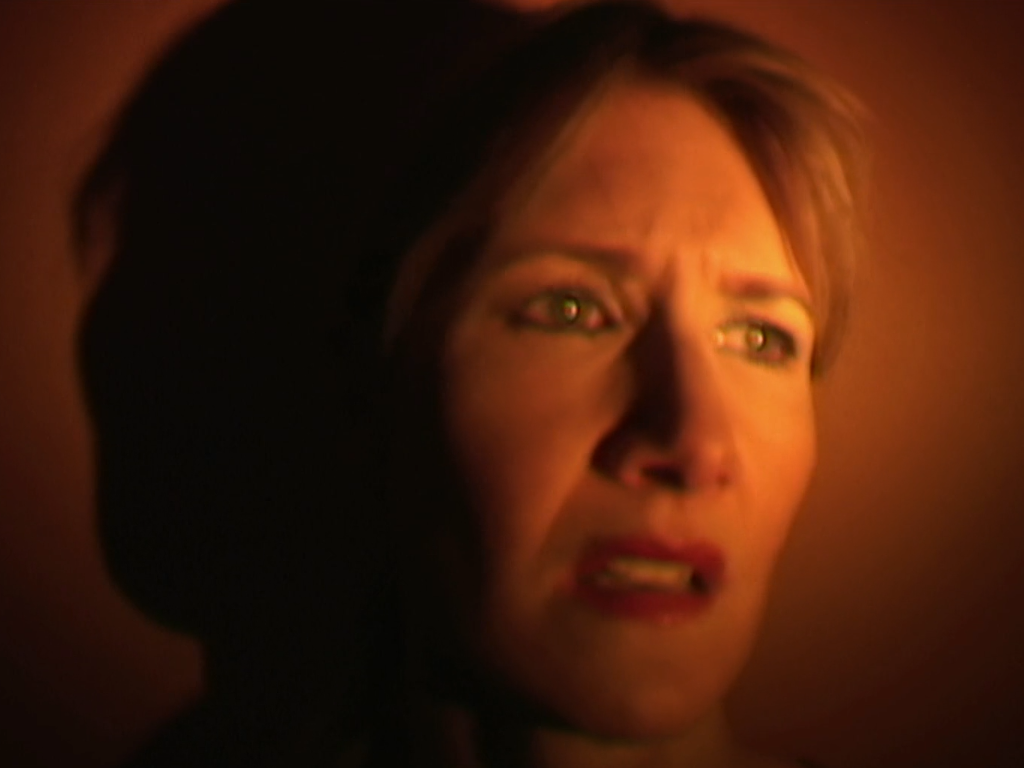

As an actress begins to adopt the persona of her character in a film, her world becomes nightmarish and surreal.

So strange, what love does

When you’re all alone

Strange, what flies with ghosts of love

“I figured one day I’d just wake up and and find out what the hell yesterday was all about. I’m not too keen on thinkin’ about tommorow. And today’s slipping by.”

Laura Dern as Nikki

“Normally, you write a script and the script is based on idea's, if it's an original script. So you try to catch idea's. If the whole thing doesn't unravel into one idea you get fragments. And when you get a fragment of an idea, you write it down and hopefully one day you have a finished script. On this particular film, I would write it down and then go shoot it.”

David Lynch

“David Lynch, like David Cronenberg, works in a corner of popular genre that is congenial and conducive to his figural exploration of the body: at an intersection of horror, fantasy, and surrealism. Sometimes the touch of the supernatural or other-worldly is heavy (as in the Twin Peaks saga, still unfolding), keyed to apparitions and presences in the external world; sometimes it is internal, springing from phantasms or disorders of identity (as in The Elephant Man (1980) or Mulholland Drive). In this generic realm, the philosophic questioning of the sovereign self, the making-strange of the relation of body to mind, the generalized experience of psychic dissociation, the difficult transaction between a Self and an Other, all come easily with the territory: tales of doppelgängers or body snatchers; people with spirits getting inside their skin or their voices suddenly issuing from somewhere or someone else; paradoxes of time lived as a Möbius strip, the end always meeting up, chillingly, with the beginning; the melding of the human with the technological; or the eternal mystery (that every child wonders about) of what’s going on inside the body, amidst all those veins and organs and fluids. The handy, even frankly clichéd tropes serve to condense and literalize, on screen, what are often complex metaphors or arguments – a profoundly figural process.”

Adrian Martin1

“Fantasy allows us to discover our freedom only when we cease regarding it as an escape from our reality and begin to see it as more real than our reality. The real becomes visible in the obvious fakery of the fantasy. By identififying fully with one's fantasy as what is real, one values the fantasmatic distortion in being over being itself – and thereby privileges the gap in the structure of ideology and the breach in the reign of causality. By embracing one’s own fantasy publicly and giving up the idea of one's own fantasy as a private retreat from the world, one accomplishes the ethical act.

Cinema is the privileged site for facilitating such acts because its very form involves the public screening of private fantasy. But in order to realize the ethics of fantasy, cinema must find a way to take fansay to its end point. This is what David Lynch accomplishes by isolating the world of fantasy as a distinct realm within the filmic experience. He enables us to see how the insistent devotion to one’s fantasy thrusts the subject into the realm of freedom. Rather than being an imaginary retreat from an unpleasant reality, fantasy becomes for Lynch the path that takes us beyong the false limitations that make up our everyday reality. Through an absolute commitment to our fantasies, we change the nature of reality itself.”

Todd McGowan2

- 1Adrian Martin, “The Havoc of Living Things,” The Third Rail, 2015.

- 2Todd McGowan, The Impossible David Lynch (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), 223-224.