“The plot of Right Now, Wrong Then is formed by a minimal situation upon which a delay and a set of variations of brief scenes are established. Hong’s narrative method lies in delaying the initial premise that would normally be immediately developed by other filmmakers in order to reach a satisfactory resolution. Rather, Hong’s minor-key story is structured in a way that never fully closes what it started; when the main characters have left the screen, the film may be finished, but the ending remains open to all possible universes. In Right Now, Wrong Then this entails the premature arrival in Suwon of, yes, a filmmaker, Ham Chumsu (Jeong Jae-yeong), to present his latest film at a festival and deliver a talk. Because he’s arrived a day early by mistake and has free time, Chumsu decides to visit a temple where he meets Yoon Heejun (Kim Min-hee) – a beautiful, wistful young woman who aspires to become a painter – in the room of the temple devoted to receiving blessings. After a chat in the temple they leave together to have a coffee and then go visit her atelier; later on, they dine and drink together, then pay a visit to some of her friends. Finally, Chumsu walks Heejun home, where she still lives with her mother. Next day, he presents his film, and has a particularly rancorous exchange with the moderator of his Q and A. That’s all. [...] “Beautiful shots such as these are speckled throughout the film without being over-stressed – they are there for those who look carefully – and taken as a whole these represent a truly astonishing visual regime that traps in its spell those viewers who are open to it. It wouldn’t be such a bad thing to stay and live inside of Right Now, Wrong Then. This is a kind and beautiful film. And those are in short supply.”

Roger Koza1

Francisco Ferreira and Julien Gester: We know that Right Now, Wrong Then is the title of your movie from the festival program, but in the opening credits, before we know this film will have two parts, we see it’s called Right Then, Wrong Now. One might think that you’d changed the title at the last minute before the world premiere. This leads us to something which is not new in your films but was never so clear as in this one: the notion of déjà vu, something that is not conscious in real life but that cinema can reproduce as a construction.

Hong Sang-soo: We could say that, yes. I didn’t think about déjà vu as the basis of my formal structure and yet… Well, in the second part, the character of the director doesn’t know the girl he meets. We cannot say that she reminds him of someone or something from his past. But the audience knows him and knows her when the second part begins. But I did give Jeong Jae-yeong the instruction to act as if he had an immediate, strange connection with her, a strong sympathy – to feel like you know her, but you can’t explain why. In this sense, talking about déjà vu makes sense.

As you explained in the press conference, you shot the first part, edited it and then showed it to the actors, so the actors were aware of how the situation was structured, even if their characters in the second part are not. Perhaps because of this, in the second part one could say that there is some kind of moral improvement, even an elevation, in the way they relate to each other. But maybe déjà vu is actually what makes certain that everything doesn’t go perfectly the second time around, because it’s a troubling feeling.

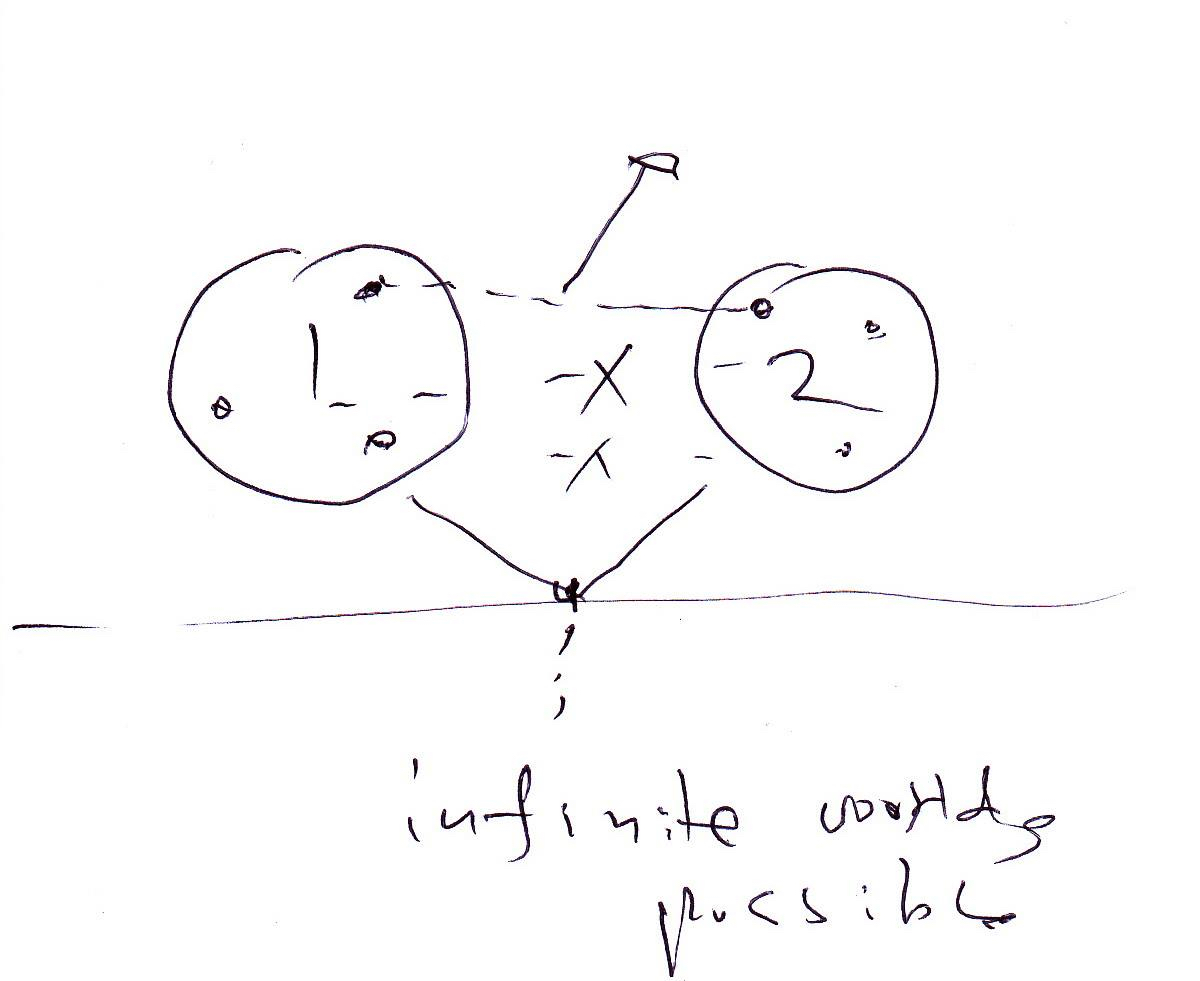

In comparing these two parts, if I can call them parts, some elements can be well connected and make the audience feel that they can explain the difference between the two in terms of morals and attitudes. But some elements are not meant to be like that, and the two worlds are meant to be quite independent. If one is able to offer a clear explanation about the relationship between the two parts, then that can be a pleasant thing. But that encloses everything… You know what I mean? This way we can proceed with some pleasure of making sense, but still feel that the two parts are quite independent. Not one moralistic message. Let me make a drawing…

Just look at these two circles in the drawing as two independent worlds. If you believe there’s a clear reason for these two worlds to exist, once you find a clear meaning between them, then these worlds themselves disappear. Once we make clear sense out of these two worlds, they are just used up. It happens that it’s not easy to give them a clear meaning. So all the questions are kept alive if there’s an infinite possibility of worlds. It’s like a permanent reverberation.

Even though the two parts are parallel worlds, still, continuity is important in the film, the fact that the second part comes after the first one. If you were doing videos for an art gallery, you could show both parts on two screens at the same time, and things would happen in a parallel way.

Even if you put it together like that, you have to see something first, then something next. You can’t avoid the time frame. What’s important is what you think over the course of the experience of going through that time frame.

Francisco Ferreira and Julien Gester in conversation with Hong Sang-soo2

- 1Roger Koza, “Infinite Worlds Possible,” Cinema Scope 64 (2015).

- 2Francisco Ferreira and Julien Gester, “Infinite Worlds Possible,” Cinema Scope 64 (2015).