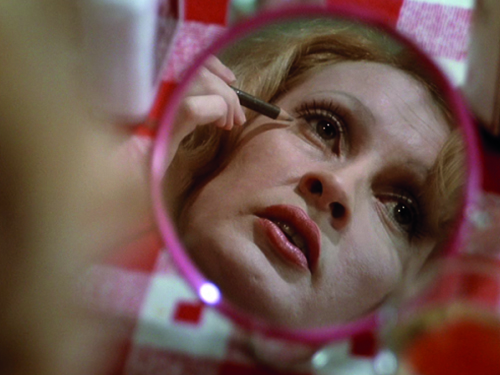

Factory worker Küsters, faced with the threat of redundancy, kills his boss and commits suicide. His widow finds herself deserted by her family and friends, until a wealthy communist couple decide to make political capital from her plight.

“My subject is the exploitability of feelings, whoever might be the one exploiting them.”

R. W. Fassbinder

“Emma Küsters earns her living assembling electrical components, for which she is paid per piece. Working from home has advantages, as she can do her quota when it suits her and work does not interfere with her domestic duties such as cooking and cleaning. However, it renders her lonely and most likely does not allow her to earn as much as if she worked in a factory. She does not even perceive herself as a worker in her own right, but only as the wife of a factory worker and the mother of his children, as conveyed by the film’s title. As an industrial worker laboring at home Emma exemplifies a woman’s condition of carrying a double or triple burden, as well as the postmodern condition of the working class, marked by fragmentation and loss of visibility.”

Ewa Mazierska1

“Throughout Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s film Mother Küsters’ Trip to Heaven, almost all of the characters utter the word “aber,” (“but”) letting it hang in mid-air between a sentence and an alternative they seem unable to express. Indeed the family at the center of his drama, the Küsters, certainly have a lot of reasons to seek for other explanations to what appear to be the facts, since the work begins with their husband and father killing the bosses’ son before committing suicide, after, apparently, learning that he would be among the employees laid off from work.”

Douglas Messerli2

“We never asked much. My husband never complained. Maybe he’d said, it was tough today, but that was all. He accepted his superiors. We just lived our lives, day in, day out, without asking each other much. Maybe I should have asked him more. Perhaps he had troubles. He just bottled them up.”

Emma Küsters

“As a stand-in for her dead husband, who can be rendered a madman, a terrorist or a revolutionary, she is approached by people representing various political interests. [...] The paradox of the situation, capturing the political mood of the 1970’s well, is that all these organisations are official left-wing, yet all of them are in deadly conflict with each other. Their fragmentation and conflicts make them behave like capitalists, ruthlessly fighting each other for a diminishing market share of the electorate. […] The need to act effectively leads to treating individual people, such as Emma Küsters, merely as pawns in their political game. In his criticism of institutions representing the left Fassbinder joins forces with Karmitz and Godard, who were scathing in Coup pour coup and Tout va bien about French trade unions. Yet, Fassbinder and Karmitz differ in their characterization of the grassroots. Karmitz and Godard furnish the striking women with the ability to change their lot. Fassbinder denies the working class woman agency and understanding, presenting her as if at the mercy of larger forces. Not surprisingly, for the authors of the review published on the World Socialist Website, this feature constitutes a crucial weakness of the film:

Sympathy for the victim, without confidence that the victim can overcome his or her victimization, is the movie’s and its creator’s great failing. Fassbinder never entertains the belief, one is aware throughout, that the class of people for whom he feels great empathy can actually carry out a radical social transformation. […]

Although I agree with their assessment of the way Fassbinder perceives working class people in this film, I will attribute this perception not only to Fassbinder’s inner transformation, but also to his awareness that in his time class dissipated, thereby becoming lonely and vulnerable to political manipulation, while Karmitz and Godard still perceive the working class as a cohesive group aware of its class interests, as a class for itself.”

Ewa Mazierska3

- 1Ewa Mazierska, From Self-Fulfilment to Survival of the Fittest. Work in European Cinema From the 1960s to the Present, Berghahn Books, 2015, 112.

- 2Douglas Messerli, “Rainer Werner Fassbinder | Mutter Küsters’ Fahrt zum Himmel”, World Cinema Review, 2017.

- 3Ewa Mazierska, From Self-Fulfilment to Survival of the Fittest. Work in European Cinema From the 1960s to the Present, Berghahn Books, 2015, 114.