No Vacancy

On the Cinema of Wes Anderson

Wes Anderson shares many of my predilections – educational film forms, the photographs of Jacques Henri Lartigue, the Futura typeface, Georges Perec, Benjamin Britten’s children’s operas, Moby-Dick, the Nouvelle Vague, scouting techniques, Jean Painlevé, miniatures made of wood and papier-mâché, lavish interiors, James Baldwin, historical faits divers, Jacques Tati and... enumerations.

There was a time when I loved his work because it invited me to come and live in it. The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) inhabit their house as if each room were a signifier of a mental state rather than a space with a specific practical function. A bedroom is for dreaming about distant travels, the tent on the landing for wallowing in heartbreak, the roof for reclaiming your freedom with the help of a hawk, the bathroom for dreaming of suicide, and the game room for quarreling. The family lives together and yet everyone has a space where they can indulge in their own obsessions. Summer’s End in Moonrise Kingdom (2012) is a similar amalgam of chaotic workspaces, secret little rooms, storage spaces, childhood memories and romance. Many of Anderson’s houses are reminiscent of a dollhouse with an opened fourth wall. The camera glides past walls to look in at the character in the adjacent room. Watching feels like playing because it has something of a puppet show with its tricks and treasures.

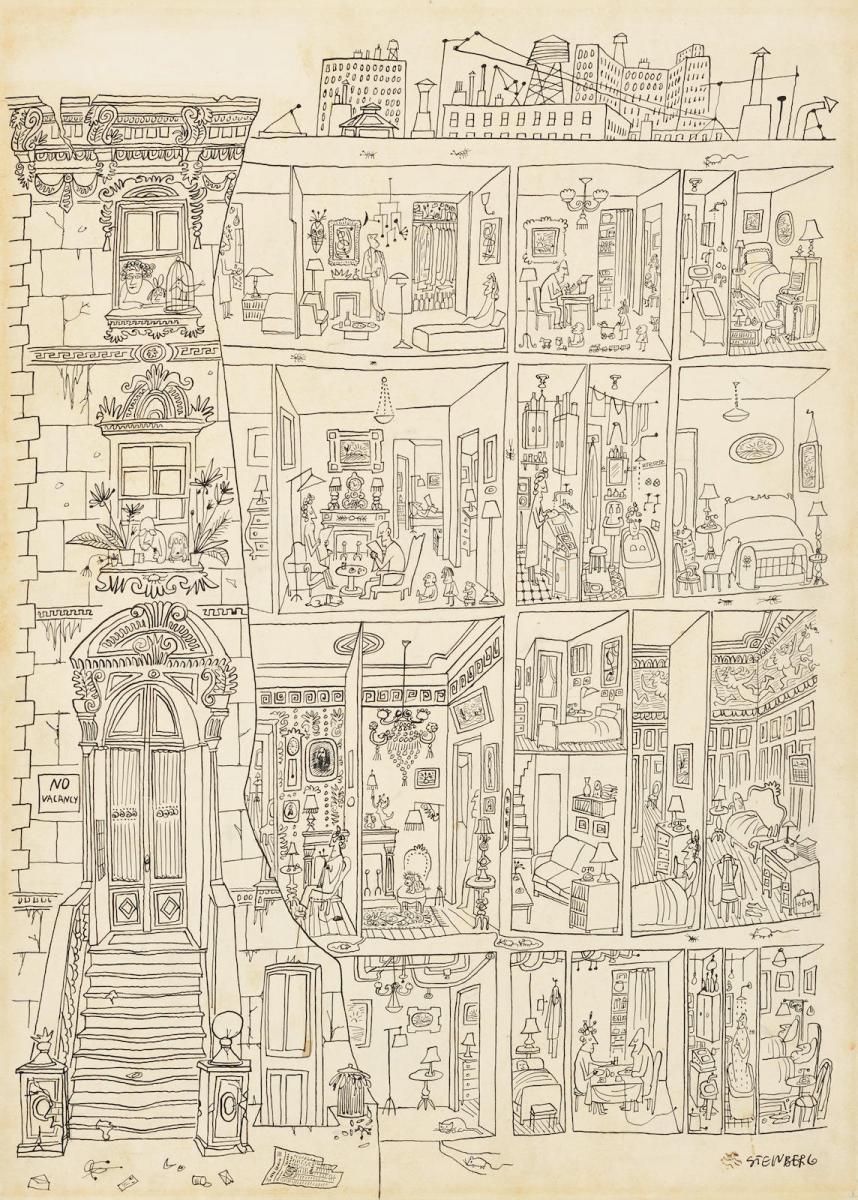

I could elaborate on each item on the above list, but the writer whose work has channeled my appreciation for Anderson for a long time (too long?) and added depth to his films for me is Georges Perec. It’s Perec who exhaustively described the visceral relationship between people and places and mapped the power of objects in our lives. Perec pointed to a drawing by Saul Steinberg titled No Vacancy as one of the sources of inspiration for his masterpiece Life a User’s Manual.1 The drawing depicts an open-plan apartment building in which you see, among other things, a writer trying to work while his children play; the empty room of a pianist; some sleeping pets; a woman bathing in a messy bathroom, the tub filled to the rim; a complete family reading and all the little things around them. They’re figures in a dollhouse that’s visible but also mysterious, displaying itself and yet closed in on itself. They live together, shielded from each other by walls.

Life a User’s Manual features dandies, inventors, ruined millionaires, servants and world travelers, all types who seem to have just walked out of an Anderson film. Thinking about Anderson’s oeuvre, I see a frontal shot in which a carefully dressed character looks at the camera while performing an idiosyncratic action. This is how we encounter young Gilbert in the chapter ‘On the Stairs’:

Gilbert Berger hops down the stairs. He has almost got to the first-floor landing. In his right hand he is holding an orange plastic dustbin out of which poke two out-of-date directories, an empty bottle of Arabelle maple syrup, and various vegetable peelings. He is a lad of fifteen with a mop of blond, almost white, hair. He is wearing a check linen shirt and broad black braces embroidered with a design representing sprigs of lily-of-the-valley. He has on his left ring finger a tin ring of the sort generally found as free gifts with chemical-flavoured bubble gum in those blue wrappers labelled To Give Is a Joy, To Receive a Pleasure and which have come to replace standard gift packs, and which you can get for a franc from the vending machines outside stationers’ and haberdashers’ shops.2

The book is a description of a painting Mr. Valène hopes to make of the cross-section of the apartment building where he lives. It soon becomes clear that this will be an exhausting task: almost every object leads to a story about its genesis and a succession of former owners revealing intertwined life stories. In like manner, shreds of paper, recipes, announcements, charters, or letters are read out loud in the novel as possible clues to the revelation of some connection or intrigue. The book is over 600 pages long yet hopelessly incomplete: every description leaves things out.

Perec seems to have inspired Anderson not only for the many character introductions but also for his narrative structure. His films are characterized by plot twists deploying motifs of forgery, confusion and disappearance. When you read the passage from Life a User’s Manual about the discovery of the vase that was supposedly used to collect the Blood from the Wounds of Jesus – out loud, at high speed, in a monotonous voice – you automatically see a sequence before your eyes.

Mandetta had disappeared a full six months ago, and the detectives hired by Sherwood were still searching for him fruitlessly on both sides of the Atlantic. It was then that a sublime coincidence occurred. Longhi, the Italian workman who’d been landlord to the fraudulent Mandetta-Van Schallaert, called on Sherwood. He had been working at New Bedford, and, three days before, he’d seen the student coming out of the Hotel Xiphias. He’d crossed the pavement to speak to him, but the man had got into a buggy and driven off at a gallop.3

What follows is a series of precipitous scenes of the transaction of the Vase against two hundred and fifty bundles of two hundred twenty-dollar bills – rediscovered years later in the hands of a group of Argentine counterfeiters. You soon lose track, but it seems as if Perec wants to take the project from a schematic set of storylines to an unbearable completeness, resulting in a hilarious complexity, which at the same time has something tragic about it. The reader’s memory will never be able to connect all these stories, take in all the details and appreciate the describer’s megalomaniacal work, even when the describer’s very existence depends on the promise of completeness. The painter Valène imagines his painting depicting every room of the house, as well as all the objects in it. “[A]nd all around, the long procession of his characters with their stories, their pasts, their legends”, after which he starts a never-ending list from which I made the following chance selection:

161 A handsome pilot looking for the castle at Corbenic on a map

162 The carpenter’s workman warming his hands at a woodchip fire

163 The so-called Russian who solved every brainteaser published

164 Visitors to the Orient trying to solve the magic ring puzzle

165 A lady who owned a curio shop fishing for a malosol cucumber

166 A princess who said prayers at her regal granddad’s bedside

167 A ballet maestro beaten to death in the U.S.A. by 3 hoodlums

168 A manager who managed to be away for four months in the year

169 The man who saw his own death warrant in a newspaper cutting

170 The tenant (for 6 wks) insisting on full checks on all pipes4

Wes Anderson could film any of these sentences. He would take one-and-a-half to two seconds for each scene. In literary form, the pacing and abundance is both a tour de force and a “game of fantasy” for the reader. In cinematic form, it’s no less of a tour de force but above all force-feeding. While a literary universe can be infinitely complicated, a cinematic universe is limited (extended!) by time and thus by rhythm, which means a film can become too full. A writer can ask more of readers exactly because they have control over their reading. A reader actively absorbs, but a viewer has no power over tempo, rhythm and excess. Unfortunately, in recent years, Anderson has made just this excess his trademark.

The list I started this text with includes a number of names. Anderson often makes “intertextual” connections and references to other (literary) work, but rather than lending his films a deeper meaning these references and finds are often merely used as a gimmick. This is particularly true of his later films.

Above the house in Saul Steinberg’s drawing, the modern world imposes itself. In the background, apartment buildings are rising from the ground, giving us a taste of the future. Houses like this one, together with their dreamy inhabitants, temporarily resist modernity. This brave house reminds me of Monsieur Hulot’s, which is authentically inefficient in contrast to the Arps’ modern home; he has to take several flights of stairs and pass through many doors before he can enter his flat with its sky-blue one. Anderson took Hulot’s house as a model for The French Dispatch (2021).5 But whereas in Mon oncle (1958) we simply follow Monsieur Hulot’s route, in The French Dispatch we get to see a worked-up version accompanied by a voiceover serving up historical details about the character at high speed. The reason behind this cinematic reference is purely formal and has nothing to do with Monsieur Hulot or Jacques Tati’s oeuvre, as if motivated by nothing more than its “Frenchness”.

Anderson seems to take pleasure in the fact that the excess of visual, aural and textual information makes any interpretation impossible. I sit in my seat and experience the film as a ride. In Asteroid City (2023), I travel along on the train and the many lateral tracking shots, but the stories about the half-orphans, their extraordinary discoveries, and the theft of an asteroid by an alien leave me completely indifferent.

Lethargy and despair lurk beneath the profusion of forms and the parade of objects in Perec’s work,6 as they drag their possessors into grave prehistories and false promises of prosperity. In the long run, his exhaustive descriptions seem to become increasingly desperate. Anderson too, in his latest films, tries to give an exhaustive enumeration of objects, characters and histories. But his is a swaggering display of excess lacking any reflection on completeness. There is no breathing space, no vacancy for contemplation.

The characters are turned inside out – closed and yet an open book. In The French Dispatch, for example, Timothée Chalamet asks Frances McDormand why she’s crying. She says without a hint of emotion: “Tear gas. Also, I suppose I’m sad.” Cut to the next pun. Anderson’s characters are not only tormented, they also articulate this fact quite literally. The dissonance between monotonous diction and explicitly emotional text creates a humorous effect. The editing neatly lays out each shot. It seems as if Anderson has established a pattern that he follows meticulously with every film. This is why it makes less and less sense to talk about any one film in particular. The themes and colour schemes are different, but the visual gimmicks, the dead-pan humour, the actors and their acting are the same every time. The last time I was forced by curiosity to see a new Anderson film, the atmosphere in the room was flat. Occasionally one person would laugh, increasingly quietly, as if frightened that people would turn to him: “Why on earth are you laughing?” All energy went into following the text and visual cues. Whereas in earlier films like The Royal Tenenbaums I felt like I was playing along with the film because there was the freedom to look around and establish connections, actively puzzling together the many rooms and rebuses, Asteroid City is playing by itself, all alone. I’m watching a music box unwinding at double speed, but any sense of a space, any notion of time has disappeared. Apathetic fatigue is the result.

Now that the mechanisation of the Anderson process has been completed, there is no longer any need for a viewer. The films wind up and play to the tune “A new masterpiece by Wes Anderson!” The painter Valène’s tragedy is that his painting will never be finished because it would have to be so enormous that there would be no room for it in the world. The tragedy of the filmmaker Anderson consists in the fact that he does finish his work, leaving no room for a spectator and causing his films to cannibalize themselves through their methodology.

Anderson’s style is so consistent that you can recognize his signature in a split second. His look is iconic to the extent that style magazines are giving tips on how to decorate your home Anderson-style.7 If you were to feed his high-strung music box movies to the latest AI machine, it would be able to reproduce them. The trailers for Star Wars,8 Dune,9 The Lord of the Rings,10 and a few other classics in an Anderson-style remake have already been generated. The films themselves will follow later, as the “Wes Anderson” trademark has made the filmmaker redundant. No one lives here anymore.

- 1Saul Steinberg, The Art of Living (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1952).

- 2Georges Perec, Life a User’s Manual, trans. David Bellos (London: Vintage, 2003), chap. 4.

- 3Ibid., chap. 22.

- 4Ibid., chap. 51.

- 5Sinemalogi, “The French Oncle by Wes Anderson and Jacques Tati,” uploaded on May 15, 2022, Youtube video.

- 6For instance, in the novel Things: A Story of the Sixties (1965; French: Les Choses : Une histoire des années soixante) a young couple becomes increasingly enthralled by material wealth. They dream about the objects their friends already have and those they see in fashion magazines but come to experience a growing feeling of claustrophobia and emptiness.

- 7Radhika Seth, ”How to Make Your Home Feel Like a Wes Anderson Set,” Vogue, 9 December 2021.

- 8Curious Refuge, “Star Wars by Wes Anderson Trailer | The Galactic Menagerie,” uploaded on April 28, 2023, YouTube video.

- 9AI Show, “Dune by Wes Anderson Trailer | Dunerise Kingdom,” uploaded on May 23, 2023, Youtube video.

- 10Curious Refuge, “Lord of the Rings by Wes Anderson Trailer | The Whimsical Fellowship,” uploaded on May 9, 2023, Youtube video.

Images (1) and (5) from Asteroid City (Wes Anderson, 2023)

Image (2) No Vacancy (Saul Steinberg, 1952)

Image (3) from Mon oncle (Jacques Tati, 1958)

Image (4) from The French Dispatch (Wes Anderson, 2021)