Dreaming of an Expedition

Sabzian publishes ‘Dreaming of an Expedition’ together with a new text by Rudi Laermans, in which he takes a closer look at the biographical and other contexts that colour Dirk Lauwaert’s essay.

1

The nineteenth century invents exoticism and makes it readily available. Through countless optical devices, the alien has come ever closer. The alien in which one is unfaithful: to one’s own fate, one’s own sex, one’s spouse, one’s own country, one’s own culture. Our century selected film as the instrument of that exotic adventure. An adventure that, if not over, certainly seems to have begun a whole new cycle.

Exoticism puts you elsewhere, shifts you, rearranges the relations between body and imagination, between looking and knowing, between the consciousness of something outside oneself and self-consciousness. The entire substance of the psychological apparatus, the entire weight of the moral and factual order of things is tipping over. Not into a revolutionary, once again definitive recalibration, but into something that remains provisional, inconsistent and half-hearted. Film changes everything and leaves everything untouched. It is the realm par excellence of what is doubtful, dubious. With this kind of slipping, film drives a wedge between the certainties of the world.

(Film is indeed always the other country – America, France, Italy. It is a way of travelling, of seeing how people live elsewhere, how they do so in other landscapes, other houses and cities. Wearing other clothes, with strangely unfamiliar ways of moving their bodies, with other sounds and intonations to express their feelings. It is a permanent world exhibition, an inexhaustible encyclopaedia in which nothing ever becomes banal.)

2

The temporarily abandoned boy looks at a projection in his grandparents’ home. A beloved uncle stretches a canvas, dims the room and makes boyish jokes as he starts up a prehistoric wooden box from which light bursts out with roaring violence, making moving figures (Chaplin?) flop down onto the sheet. He did not see the depth of the image as much as the flat projection on the canvas.

The slightly less abandoned boy sits down with the grandfather on wooden chairs in a school to watch a film about Spain, Alcatraz. He sees action, dust, explosions, sweat, suffering and death. He sees a story.

The boy goes to the big city with his father to see a Schneider film. He is in love. On the way back, his father searches his soul: to observe infatuation, as in a small cinema? The boy has seen a beautiful woman whose lips, when talking, move him to this very day. He understands (but does not accept) that she came so close to him but that he has to stay so far away from her.

Three phases: the image, the story, the woman. A few more films. A few more impasses and life has put him in the position of the one who prefers the dark room, the distant image, the kitschy melodrama over all the temptations of reality. Fortunately, there was film. To love film – he discovered much later – is to be in Oedipal impasses without which film is at best mere entertainment. (When a culture, through a changed family structure and gender relations, slightly rearranges the Oedipal adventure, doesn’t the role and place of film change as well? Isn’t a certain fascination for film irrevocably a product of its time?)

3

The cinema was his America, the images followed one another like solemn seven-league strides, like running the hundred metres. He shifted from place to place, from one figure to another. And it always happened within that exact distance. Without realising it, film pulled him into a partner dance. Later, he understood that everything revolved around an oxymoron: to be moved unmovingly.

But in the cinema, all emotions are experienced exclusively inside oneself (one watches inside one’s head in the same way that one has started to read in silence). The fixedness of a cinema audience is terrifying. Their complete lack of expression looks downright dumb, like people watching the landing in Close Encounters...

Film was an empty theatre, during the day, in which artificial light showed everything the sun outside could never show. It was the most blissful way of being: all alone in the presence of an intense illusion. Life watched more fascinating than life lived. The other so much more fascinating than the self, a substitute dream for the self. (The eternal Bovarysme of the bourgeois boy, satisfied by an industry.)

Because watching is your life. Because you distrust the power over the concrete, which is necessary for life. You experience the film as essential, sublime distance. (And that distance has been removed today. Films inject sensations under your skin, they dump your body across the boundaries of the image, into the image, into the sound. And I think: perhaps that dumping is the new form of distance, a new development in the fundamental cruelty of the film apparatus.)

4

For the young man, going to the movies was also an answer to art. The boys’ game of poetic words and radical slogans did not suit him. The conformism of the literary, formulated “no” surprised him. To him, film was a place to steer clear of all those dubious rules. He chose (indifferent to the censorship of emotions) the shameless brothel of affects. It made him immune to the conflicts between art and commerce, between art and kitsch, between morality and amorality, between conservative film and progressive certainties, between sentimentality and the principle of reality.

Film was definitively a different, radically innocent, free-floating culture, without institutions, without an official language, without norms. It was a low culture, watched with great care by society for its elusive rudderlessness. An uncontrolled territory, a “third world” that anyone with the wildest of imaginations could embark for. A world, too, in which you could stake out an engagement out of nowhere, map out your own routes, invent your own genesis and give it ultimate value.

It is true, film lovers have developed their own signaletics, a rudimentary system of traces and smoke signals, in which they only give directions to the initiated. No meetings, no common language, no clauses to which the game could be subjected. Long-journey trekkers never meet. They leave their tracks in such a way that no one could use them for establishing an order. They behave according to a collector’s maniacal willfulness.

5

Dealing with film became a subtle balancing act. It was certainly not enough that they propagated the right conviction, it was not enough that they looked beautiful, it was enough that they felt alive in order to be admired. The criterion was not originality (which happens when film becomes art) but the perceived undeniable rightness with which the images were put on the screen, with which the images set themselves against the world. It didn’t matter that others experienced this rightness in places where you didn’t. The category is what mattered.

A powerful means of bringing out this rightness was constant rewatching, but also the comparative repositioning of the films, in subtle moves in which qualities became ever more subtly weighted. The smallest distinction contained the biggest difference.

6

There are films you watch with him, the man, and others you watch with her, the woman.

The film always puts you in a sexualised relationship. In the theatre, you forget your own gender, but never gender as such. Images, bodies and story send you back and forth in that engine that once addressed and “resolved” your sexual identity. The film switches that engine on again and lets the game go its own way, gives you the illusion that the game of chance could have turned out differently. Because in the cinema, you change sex. At least, it is a magic that delights the film lover.

No matter how conformist the stories, role divisions and prejudices, something radically different happens in the reality of the viewing experience. It is this very conformism that generates in him a shameless travesty. It is conformism that makes these shifts possible, that revolutionises the viewer. What naivety on the part of those who think they have to emancipate film! It is the very bourgeois clichés that make everything explode.

7

The watched film is a magic garden for abandoned sons entangled in Oedipal impasses – this is what a film lover’s profile often looks like. They walk alone in the forest of the seven sons where fathers betray them and others eat them.

Then again, filmmaking is the realm of the father (the dreamed father, the feared stepfather). He shows woman to the sons. The sons look through the father’s gaze. The sons discover a form, a style, an attitude, a moral, a possible answer. But the father shows the truly unattainable: the sons have to make do with the image. They are grateful to the father for the view and ask no more, which is why they keep going to the movies. Even when they have long since left the Oedipal phase. (How do women like film? Or do they just accompany their friends and men, worried about their restless wandering?)

8

The fairy-tale belief in photographic images no longer really works. That belief went as follows: because of its photographic basis, film is an undeniable registration. Realistic not because of a stylistic choice, but on the basis of its operation of registering. It is always a technique of and in the world. The equipment links the film to the world in a radical and astonishing way via a technical umbilical cord.

So watching film and loving film are ways of being with the world. Albeit in a roundabout way that is simultaneously a revelation: a revealing distance. Film is therefore essentially a relationship, not a code. Film is fundamentally the choice of a position in space towards a space.

Film is registration and therefore fundamentally contemporary (one cannot register what is past). The spectator always watches contemporary images (even if they have become old, they remain contemporary as a model). This disposition makes that whoever loves films becomes “contemporary” with every film.

That is why the idea of the classics fails in film: it is a first attempt to install a timeless norm, a law. Film is therefore not only an instrument of distance but also a wondrous way of being with the world. Current affairs are not like that, its theme is not that which is contemporary but that which is out of date. This contemporariness is an instantaneous kind of anthropology that has fuelled the awareness of living in one’s own world with every fibre of being: the true basis of a political and historical awareness. Or how industrialised dreams fed the consciousness of history as a place of injustice and crime. There is, by the way, a generation that was traumatised into history by that one film by Resnais. With objective registration of the unimaginable, the unthinkable. After that, life has never been the same.

9

Photographic images are poor. What we see is so familiar that it never overwhelms us. Take, for instance, a shot from Rohmer, Rossellini or Chaplin: there is so much banal visual noise in their images that they start breathing for that very reason. They have and therefore give space, so that as a spectator you can move, as if the image itself were effectively an open situation. That is why their visual banality acquires an unlimited aspect, like reality itself.

Today’s images are being stuffed ever fuller, like a container loaded to the limit. Images chock-full of money, power, cynicism, chock-full of manipulation of meaning, chock-full of ideas too. In the cinemas, these images are now moulding the first generation of the second century of film. These images provide an ideal critical education with regard to images. One learns how to treat images in a sceptical, suspicious, even hostile, and contemptuous way, to the delight of the spectator who enjoys being and thinking more than the images he sees. No one in the next century will understand the glorious madness of those who looked up to film. These detached, conscious consumers take up a position that is not a far cry from suspicious moralists.

What challenge could they offer, the images of today luring the spectator, sitting in the brothel window called television? What to do with images that always agree with you, that are there to know and fulfil your desires? What to do in the future after so many images without a future – as there is no money to be made in the future!

10

A crucial question for those who watch films and want to test their meaning, the world and themselves against it, is the question of the future of that past.

The museum is the institution that gives ready-made and too numerous answers to this question without having listened to the questions. An institution is therefore always something that prevents questions and (new) answers. The museum must simply know what its heritage is, how it should be shown and preserved, and why. The museum is therefore the place of the classics, of authors and of their oeuvre. Nobody seems to believe in it anymore, but it remains.

The academic reflex gives a second answer. It says that films and film-watching are not the core, but that we find ourselves in front of objects that we analyse according to a method to be verified, which often comes at the expense of the film and the film experience itself. Here, one makes room for the typical film, the model film of the film. It is the place of the fragment.

In this context, film is at the mercy of very poor counsellors. Those who love film are faced with opponents who are as obstinate as they are embarrassingly insignificant. Once again, one must fight against moralising readings. Once again it must be said that the film experience is crucial, that this experience is physical-erotic. Once again it must be said that its support is neither celluloid nor magnetic tape but the social self. As simple as it is immensely complicated, the link of each fragmentary “I” to the immense world, of the democratic citizen to the lost whole, has been invaluable to our century. It has made us.

11

A dream. I gird on the minimum. A sporty outfit to be agile and flexible. I am lowered by a rope into the past, through the narrow hole of an archive. I make my way back through the immense labyrinth of the past hundred years. I leave all maps at home. I start from scratch. I look backwards, forwards. No longer to write another history, surely – it has been written, it suffices – but to report on experiences. For the very nature of experience is that it is capable of both confirming and questioning everything.

Wasn’t life with film above all a life of ever new questions, against the answers of good taste, culture, morality?

For over half a century, Belgian critic Dirk Lauwaert (1944-2013) published essays on film for magazines including Film & Televisie, Kunst & Cultuur, Versus, Andere Sinema and De Witte Raaf. In addition, Lauwaert wrote about fashion, photography, the city and visual art. For Lauwaert, such criticism was never a purely professional affair; it was, first and foremost, a way of documenting how a film or a piece of art personally impacted him as an amateur. Lauwaert’s film criticism is not, as yet, internationally recognised. To provide a first corrective to this, Sabzian will be publishing a series of roughly ten English translations of Lauwaert’s most notable writings on film. This will provide our international audience with an occasion to become acquainted with his work and its singular writings. Lauwaert was an author for whom “watching film and loving film [was] a way to be with the world”. Remaining suspicious of “the power over the concrete, which is indispensable for life,” Lauwaert was someone for whom the act of watching films made up his “whole life.” In this sense, film for Lauwaert turned into the experience of that “essential, sublime distance.” A more extensive English introduction to Lauwaert can be found here.

This article was originally published as ‘Dromen van een expeditie’ in Kunst & Cultuur, nr. 1, 1995.

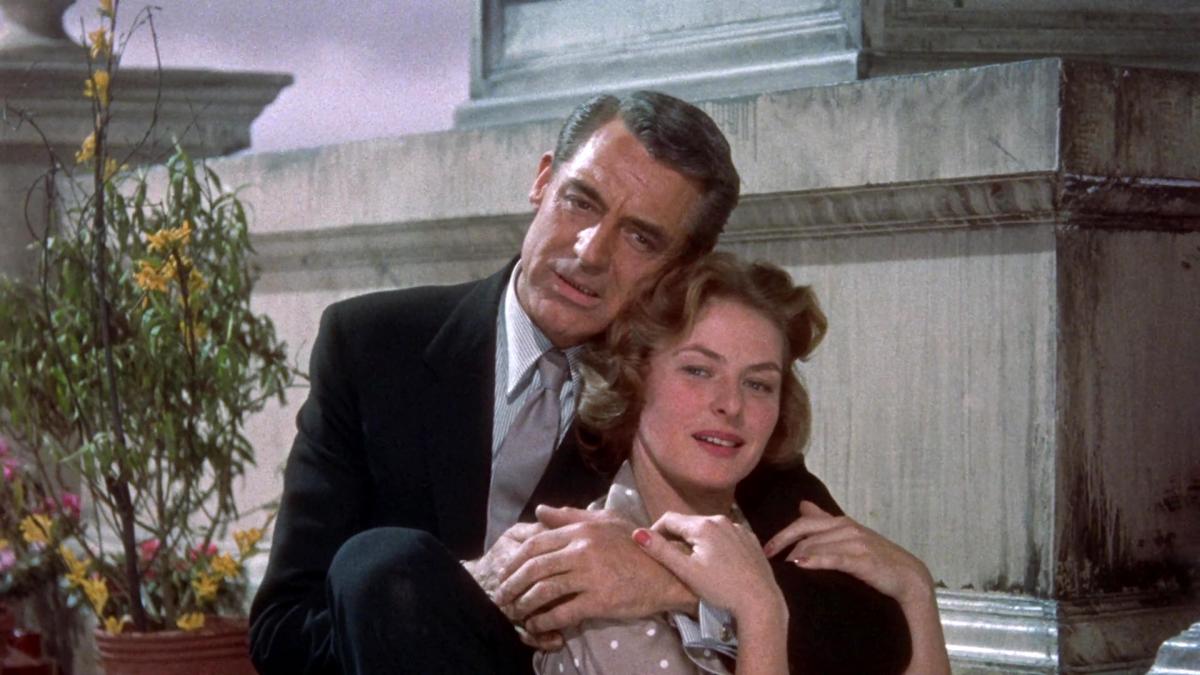

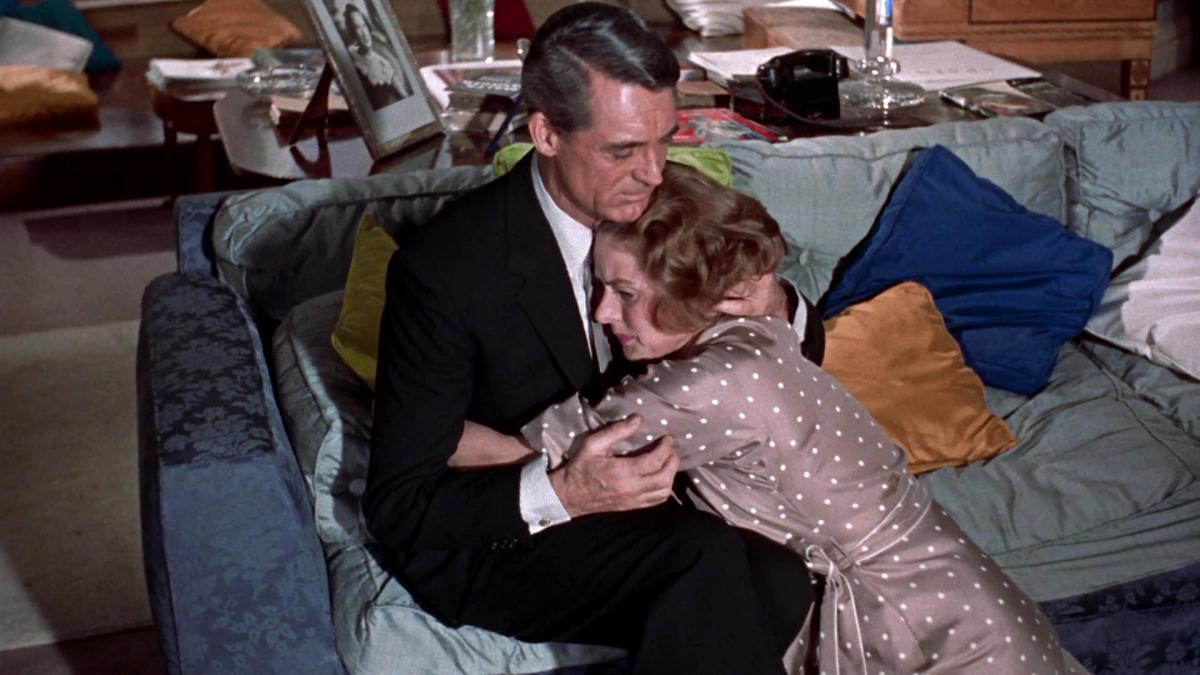

Stills from Indiscreet (Stanley Donen, 1958)