Passage: Rastko Novaković

Monoform

“Society at large still refuses to acknowledge the role of form and process in the delivery and reception of the mass audiovisual (MAVM) output. By this I mean that the language forms structuring the message contained in any film or TV programme, and the entire process (hierarchical or otherwise) of delivery to the public are completely overlooked, and are certainly not debated. In turn, this lack of critical public debate means that over 95 percent of all MAVM messages delivered to the public are now structured by the Monoform.

- the Monoform is the one single language form now used to edit and structure cinema films, TV programmes – news broadcasts, detective series, soap operas, comedy and ‘reality shows’, etc. – and most documentaries, almost all of which are encoded in the standardised and rigid form which had its nascence in the Hollywood cinema. The result is a language form wherein spatial fragmentation, repetitive time rhythms, constantly moving camera, rapid staccato editing, dense bombardment of sound, and lack of silence or reflective space, play a dominant and aggressive role.”1

I first encountered the concept of the Monoform in 2003 in an online statement. Around the same time, I saw Peter Watkins’s global peace film The Journey (1987).2 To me it remains his clearest critique of the Monoform by example. Since then, his questioning of the Monoform and his proposals for a reform of mass media have been a constant orientation point.3

Directing films in the “industry” showed me how ruthlessly the Monoform is imposed by gatekeepers who see any variation in standard shot length (three to eight seconds) as a direct threat to their professionalism and values. Contemplation, spirituality, an experience of contradictions, a rightful positioning of facts and information in a world context (which also means alongside values and assumptions) are all undermined by the overvaluing of fragmentation and speed in the service of an instantly digestible image.

But it would be a mistake to think of the Monoform as a way of editing. It is first and foremost a social relation which imposes and reinforces the dictates of consumerism, passivity and othering, so useful in nationalist mobilisation, war, electioneering, profit-making. Its bedrock is the separation into producers and consumers of mass media which prevents genuine democratic communication.

Like Watkins, I have come to believe that our sense of history gets lost in the intense fragmentation and violent separations of the Monoform, which in turn also leads to a loss of our sense of self (individual, national, species-wide). Watkins’s view insists on personal responsibility in approaching history, rather than hiding behind institutional “objectivity”. Currently we see how the democratic promise of personal, social media has been exposed in the ongoing war in Ukraine – this war operates along the same old broadcast propaganda models,4 exponentially amplified by social media platforms to dominate the public sphere and force populations into a dangerously narrow space of understanding and responding to Putin’s invasion. Where this space is seen as too wide, blanket bans on information, people/s, letters of the alphabet are imposed. In all my time of analysing war propaganda (in ex-Yugoslavia, Britain, Lithuania), making activist media and films which engage with history, I have not encountered a time in which the strictures of the Monoform, with its conventional narrative arch and proposed resolution, have been imposed so unwaveringly and unquestioningly.

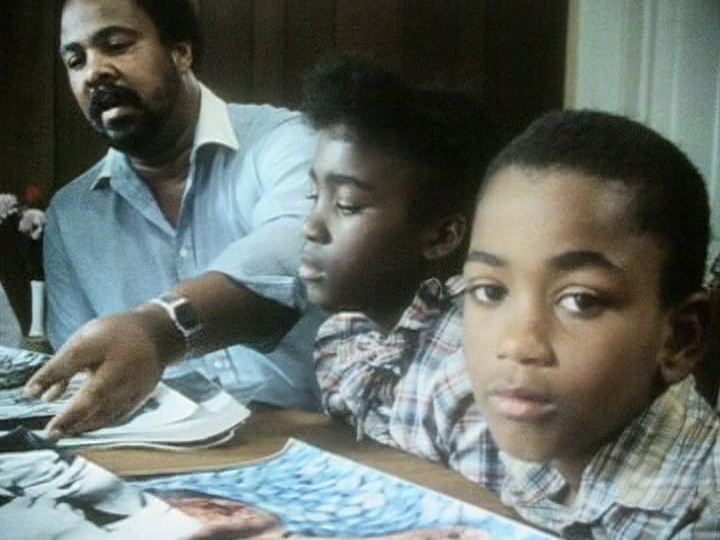

Lastly, my experience of watching and showing5 The Journey is that it successfully explodes these boundaries imposed by the Monoform. In its length (873 minutes) and call for engagement, it breaks our daily relationship to capitalism: watching and discussing for hours, returning to the space and developing relationships. This mirrors the production of the film which is a trace of how various communities and individuals worked for peace in the 1980s – their experiences flow in the world,6 into the film and back into the world. The Journey is a tool for analysing our relationship to mass media: we sit with families and communities in uninterrupted, long takes and analyse the global TV news. It is a space built for contemplation, learning, empathy. By the end of it, we have spent so much time with the people in this film, that we cannot write them off as irrelevant, foreign and other – even as ghostly images, they have become people in our world, the only one we have.

- 1Peter Watkins, “Five Years Later – The Media Crisis,” 2003/7.

- 2Peter Watkins, “The Journey”.

- 3These proposals are embodied in his films, often explicitly, but also in written statements like these.

- 4Those broadcast models have marginalised Watkins’s work, e.g., banning The War Game (1966) for daring to speak the truth about the impossibility of surviving nuclear war.

- 5In June 2022, I put The Journey on over six days of screenings and discussions at Glasgow’s CCA. Together with Lina Lužytė, Dovilė Lapinskaitė and Egidijus Mardosas I organised nine screenings/discussions in eight venues in Vilnius and Kaunas in October 2022.

- 6Some of them are still working for peace 40 years on and were doing direct action protests at the Faslane nuclear base in June 2022.

Image: The Journey (Peter Watkins, 1987)

In its new section Passage, Sabzian invites film critics, authors, filmmakers and spectators to send a text or fragment on cinema that left a lasting impression.