Une petite flânerie

Traveling as Method in the Work of Ulrike Ottinger

In 1968, Ulrike Ottinger lived as a painter in Paris in a chambre de bonne, opposite the Sorbonne, where she attended lectures by Claude Lévi-Strauss, Pierre Bourdieu and Louis Althusser alongside her artistic practice.1 During the height of the student revolt, police officers roam the streets in front of the university at night. One of their methods of repression is beating people in the street with batons. Ottinger has a recurring nightmare in which the sound of the beatings turns into a hard knocking: It is Germany in the 1940s and the Gestapo is banging on the door of the house where Ottinger, as an infant, and her Jewish mother are hiding from the Nazis in the attic. The same attic that she later uses as her first studio. In her dream, Ottinger is now in this studio – it has caught fire. She reaches for the phone in a hurry and calls Althusser – he can’t help her. Then she calls Bourdieu, who is also unable to help. Finally, she dials the number of the fire brigade. A short time later, the fire brigade is at the door, but when they enter, the helpers turn into SS soldiers and French policemen in black leather who smash everything. Ottinger herself dies at the end of this dream. These seven firemen rise from the water in the introductory scene of Ottinger’s second feature film Laokoon & Söhne from 1975, which introduces key themes such as metamorphosis, often recorded through a transformative travel, in the artist’s cinematic work.2

One year later Ottinger leaves Paris after 8 years and ends up in Berlin. A major change for Ottinger – she begins making films, as both director and camerawoman, and this was to be the beginning of a creative phase lasting more than half a century until today, which would make her a cult figure in the feminist avant-garde underground of German cinema.

Cut to: the Jewish mother who raises toddler Ulrike in hiding in Nazi Germany in 1942. Even these early years of exclusion from society seem to characterise Ottinger’s life. As a teenager, she feels “locked up”3 and leaves bland Adenauer-era-Germany to join the ranks of German-Jewish intellectuals outside of the country.4

The father: a sailor, painter and collector of exotic objects and figures. Anyone entering the artist’s office in Berlin in 2024 may feel as if Ottinger herself has become this father figure with an impressive collection of African and Asian masks and sculptures, staring down from the ceilings and the shelves.

Trumping the Oedipal complex, the sailor becomes one of the subversive figures that the filmmaker creates to provoke German heteronormative educated middle classes.5 Cultural historian Patricia White, who has been writing about Ottinger’s films since the 1980s, however describes her as a “dandy figure”6 and compares her collaboration with important feminist cult figures such as punk icon of Berlin underground Tabea Blumenschein and Delphine Seyrig to a relationship between creator and muses. Their co-creations – although still overlooked today – essentially contribute to the male-dominated New German Cinema of Schroeter and Fassbinder (who are also known to have experimented with risqué portrayals of sailors).

Genealogically, Ottinger thus appears in every respect to be a renegade of the social and sedentary norms, an outsider and an eternal nomad. As a filmmaker, she transforms this experience into a genderbending oeuvre of Surrealist and Dadaist imagery as well as ethnographic observations, in which the cultural Other is always of the utmost interest.7 In addition to a few theatre and opera productions, Ottinger’s archive consists of an incredibly wide-ranging oeuvre of photographs, paintings, artist book publications, exhibitions and more than 25 films. These include up to 12 hours of real-time documentary films (like Chamissos Schatten (2016) or Taiga (1992)) as well as neo-baroque camp aesthetics as short film fiction (such as Superbia (1986)). Today, her cinematic oeuvre is increasingly discussed either as a genealogy of feminist and lesbian film avant-garde and auteur cinema or as part of an ethnographic debate in film. Synergies between these two debates, her documentary and her fiction practice, may come to the fore in a close-up of the figure of the traveller which can roughly be outlined by three films from different periods in Ottinger’s career: Paris Calligrammes (2019), Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia (1989) and Freak Orlando (1981).

Paris Calligrammes (2019)

Ottinger’s newest film is a portrait of herself, but also a portrait of the city at a certain point in time.8 At the age of 17, she leaves for Paris, the cultural city “of the future,” of possibilities and sexual freedom.9 Paris Calligrammes traces Ottinger’s artistic beginnings, whose inspiration she finds in the cityscape, its architecture, its museums and public places, in the people who live there. One of the first chapters sheds light on the German antiquarian bookseller Fritz Picard – also a Jewish exile – who fled to France to escape the Nazis. Picard’s illustrious circle around his Librairie Calligrammes included Surrealists and Dadaists such as Max Ernst and Jean Arp, Ré and Philippe Soupault and Walter Mehring, Annette Kolb and Paul Celan, whose works made a strong impression on Ottinger.10

As already exemplified by the dream image at the beginning, one of the more important scenes that Paris offers for the film maker is the process of decolonisation, the political upheavals, the Algerian and Vietnamese War and May 68, which expose and denounce colonial Europe.11 Ottinger sees the world premiere of Jean Genet’s play Les paravents (1961) – 17 individual scenes strung together, an uprising against a colonial power in an undefined Arab country or the cinéma verité by ethnological director Jean Rouch. “In France, the ethnologists were also poets.”12

In formal terms, Paris Calligrammes is characteristic of Ottinger’s work in several respects. As a film it is organised in ten stations. The “station cinema”13 is a storytelling method, in which non-linear or seemingly unconnected scenes are strung together to create a big picture. As artistic practice it has “its roots in medieval mystery plays and was revived in expressionist theatre”.14 Ottinger herself places her camera work and her montage in the tradition of Benjaminian flânerie offering another backdrop to the filmmaker’s travelling notion.15 The flâneur, a product of the big city and its conditions, of its architecture and the infrastructures of consumption – “that figure of urban enchantment theorised by Walter Benjamin in his reflections on […] Paris: a wanderer and a witness, also implicitly male, as feminist commentators have explored.”16 Ottinger situates her station narrative in a storytelling genealogy, which is characterised by nomadic life and exposure to planetary rhythms such as the seasons. A narrative cycle needs dynamic and calm stations, i.e. nomadic and sedentary energy.17 These two archaic storytelling forms are reconciled in Paris Calligrammes’ chapters that propagate either static shots of the city’s local movements of the everyday such as street sweepers on Place du Furstemberg juxtaposed with chapters of moving archival imagery the big historical moments in Algeria or Vietnam – this dialectic is necessary according to Benjamin, in order to give the storyteller “full corporeality”.18

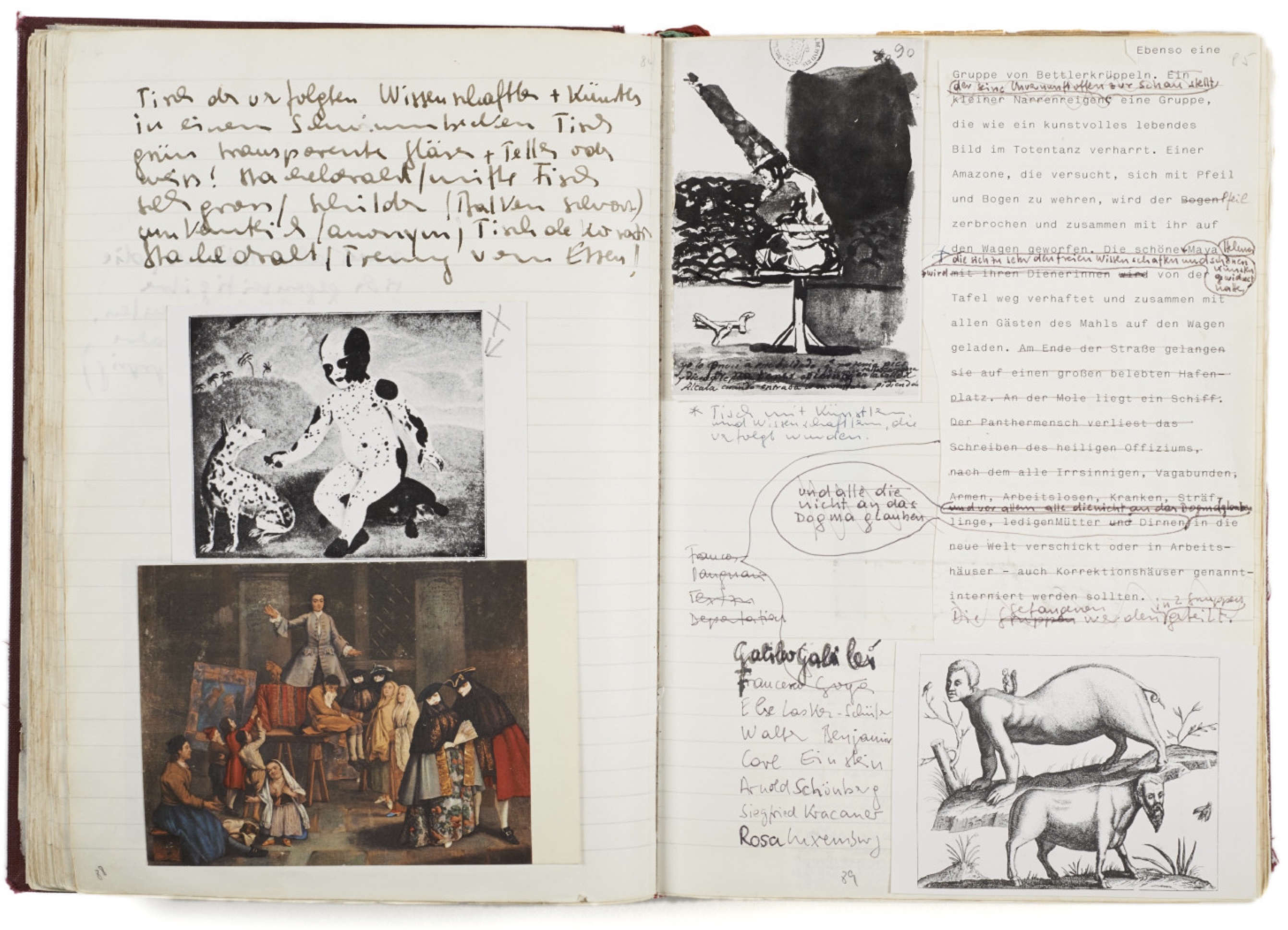

Paris Calligrammes uses the city as the metonymy of a cabinet of curiosities – emblematic of Ottinger, the quintessential traveller who documents and collects. Her artistic practice is characterised by this associative nature of collections, in which images and texts from different contexts are strung together.19 In preparation for her projects, Ottinger produces workbooks that look like scrapbooks, in which visual and literary snippets are collected in a cut-and-mix collage technique in thick books – like photo albums – that are taken to each set and serve as inspiration for all those involved. Ottinger names them “Arbeitsbücher”20 – “books to work with”.

Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia (1989)

While many of Ottinger’s films were made while travelling, Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia epitomizes the complexity of the intertwining of documentary and fictional stylistic devices. It is also the film that most clearly elaborates the archetype of the traveller, unleashing complex debates of accusations of exoticisation, appropriation and cultural Othering.21 Art historian Angela McRobbie has most recently described the leitmotif of traveling in Ottinger’s oeuvre as “a libidinous effect”22 which adeptly summarizes the energy of this film. It seems driven by an instinct analogous to fundamental life force, it is as much hungry curiosity as it is sexual desire for the Other. An in-depth look at Ottinger’s magnum opus is particularly rewarding to understand the entanglement of queerness and ethnographic exploration. Can the queer gaze really corrupt colonial perspectives, as Edward Said attributed to Jean Genet?

The film unfolds in two distinct acts. It begins aboard the Trans-Siberian Railway, transporting European travellers through Siberia’s wilderness. A dramatic shift occurs when a band of Mongolian horsewomen, led by Princess Ulan Iga, halt the train and abduct seven European women into the Mongolian steppe. This plot twist frames a rich exploration of intercultural exchange through a cast of symbolic travellers: the figure of Lady Windermere,23 embodied by feminist icon Delphine Seyrig, appears as a British, cultured, anthropologist who speaks fluent Mongolian, as a guide and teacher to the rest of the (less cultured) travel group. At the beginning of the train journey, she invites the youthful backpacker Giovanna (possibly the incarnation of the heroine of the title) to share her train compartment. A number of musical characters stand out, such as Mickey Katz, Jewish-American musical star who delights the train travellers with Yiddish hits, or the Kalinka sisters, a klezmer trio. The nomadic and the cosmopolitan are musically reflected here through the exile music Klezmer, as an example of Jewish cultural richness that has developed precisely because of its nomadic existence as outcast.

Ottinger’s entire oeuvre is interwoven with symbolism of nomadic qualities. The train is of course a symbol of the traveller, of locomotion, possibly even social progress, but here the filmmaker also draws a reference to film history. The exterior landscape that passes by the train windows in Johanna d’Arc is obviously painted on a screen and is reminiscent of the brief technological moment in which the panorama first became a mass spectacle during Enlightenment in Europe.24 In his review of Ottinger’s work, psychoanalyst and cultural theoretician Laurence A. Rickels draws parallels between cinema and psychoanalysis via the train theme: Freud apparently suffered from a traumatic train journey with his own mother and later used an imaginary train journey as a method for his sessions with patients. “The train was the first techno means of transport to travel the dotted line between trauma and entertainment.”25 The image of the viewer watching the conscious and unconscious pass by in relation to each other seems to be a key image for Ottinger’s world creation and the way we are invited in.

After the forceful halting of the train, the Mongol princess Ulan Iga orders the Europeans to get off. Initially shocked, the travelling party obediently follows. Formally and aesthetically the film changes abruptly. Everyday Mongolian life and festivities are filmed in real time and its suddenly difficult to distinguish these images from other documentaries, such as Taiga. The lesbian undercurrent, which has been evident since Lady Windermere took young Giovanna into her train compartment, becomes all the more palpable when Windermere is abandoned by Giovannia for the princess. Although they are unable to communicate with each other, they seem to develop a deep bond over wildly riding together through the Mongolian steppe. Narratives like this are reminiscent of the problematic white cis (usually male) traveller’s gaze, which propagates sexual racist fantasies of roughness and wildness as something erotic yet inferior.

“It was not my intention to create exotic images,” describes the filmmaker. “The film is concerned, rather, with the transport of culture. If exoticisms arise in the process, they are never identified with ‘the foreign’ per se but rather with the unsuccessful encounter with the foreign. My film is not devoted to exotism but rather to nomads.”26 And as a matter of fact, of all the archetypes presented to us, Giovannia seems to be the traveller who succeeds best in cultural exchange through her love liaison.

The actual plot twist takes place at the end, on the train back to Paris: The Mongolian princess is aboard and turns out to be a Parisian who wanted to indulge in a costume spectacle. Author Cassandra Xin Guan writes in a recent article: “Ottinger’s documentary eye sees the ethnographic subject not from the outside, but rather through a kind of view-within-a-view inscribed in the field of culture under observation.”27 The understanding of the view-within-a-view, the ethnographic gaze, doubly unmasked here, which we have now been able to uncover thanks to the observation of the thought (journey), shows that Ottinger certainly offers a complex and self-referential processing from her own travel experiences in foreign countries. In an interview, she describes how the film concept had already been conceived but was then put aside in order to make her first long documentary China. Die Künste – der Alltag. Eine filmische Reisebeschreibung (1985).

“Certainly, one film is a documentary and the other is a fiction film, but for me, and taking into account the respective production methods, both genres have undergone a profound transformation. Perhaps one could say that China is the encounter with the foreign, while Johanna is the staging of this encounter.”28

White suggests that Paris Calligrammes offers a key to Ottinger’s dichotomous oeuvre between documentary and fiction influenced by Surrealists like Max Ernst, who sought continuity between aesthetics and anthropological studies of non-Western cultures. This Surrealist primitivism inspires her films, reflecting an exoticizing desire which prompts a queer-generational question: does she-dandy Ulrike Ottinger, ultimately project the male gaze, akin to colonial neurosis?

In Johanna d’Arc, Ottinger unites travel epics, lesbian narratives, and intercultural themes, exploring power dynamics and idealization. Gustave Flaubert’s L’Éducation sentimentale (1869) appears as a reference introducing the concept of “pedagogical eros” – an intense, often idealized connection between mentor and pupil, both literal and metaphorical. Flaubert’s Egyptian journey, marked by romantic entanglements, shapes Ottinger’s narrative, blending intercultural fusion and sexual desire. Erica Carter and Hyojin Yoon draw on Said to identify Ottinger as an author who quotes orientalist stereotypes, but also transforms them, through a feminist or feminine way of connecting with the other culture: through the physical confrontation, “engaging in ritual performance and experimental play”29 (which is why it is so important that we experience these scenes in real time), Flaubert’s concept is finally critically dismissed through a clear feminist gesture.30

Freak Orlando (1981)

No discussion of Ottinger’s work should be without the Berlin Trilogy, which made her internationally famous in the eighties, and the trope of travelling would not be complete without a few words about time travelling.

After her formative years in Paris, Ottinger finally moves to Berlin, where she shoots Bildnis einer Trinkerin (1979), the phenomenal portrait of a female drinker which is of course also a portrait of the city of Berlin, in which the main character, played by Tabea Blumenschein, plans to drink herself to death. Ottinger and Blumenschein (who has been Ottinger’s great co-creator and aesthetically characterises her films to date) ended their romantic relationship. In the following, Freak Orlando is being released, completely different but similar as portrait of Berlin and its industrial landscapes, this time starring Delphine Seyrig as muse.

As noted above, Johanna d’Arc already seems anachronistic but in Freak Orlando, which Ottinger filmed in 1981 as the second part of her Berlin trilogy, a kind of queer journey through time is undertaken. Like Paris Calligrammes, Freak Orlando is a station cinema, a surreal historical spectacle of freaks, the grotesque and the different, radiating queer camp aesthetic. Orlando, the main character, inspired by Virginia Wolf’s well-known non-binary character, appears in five episodes in different contemporaries in different genders. For example, in historical settings such as the Renaissance and the Spanish Inquisition, as a witness to the rise of capitalism and the commercialisation of the human body and work, institutional control, for example through psychiatry, always in apocalyptic, surreal landscapes. Last station is ‘The Festival of the Ugly’ in the 1970s where the final incarnation of Orlando acts as judge and show master to nominate the greatest freak of all.

The freak show, which has been compared to Tod Browning’s 1932 Freaks follows Orlando, who transcends time and space as a universal archetype of the marginalised and misunderstood. Magdalena Montezuma,31 star of the alternative German scene, and Delphine Seyrig appear in various incarnations alongside hermaphrodites, dwarves and giants and women without abdomens. Long before queer German cinema was even a concept, the film made a powerful statement on diversity, integration and resistance to conformity, a milestone in avant-garde cinema. With Freak Orlando, the travelling topos can be placed in relation to queerness through time travel. Art historian Thomas Love has worked out the queer sense of “temporal displacement” in Ulrike Ottinger’s works:

“The role of queerness in this project is not insignificant, for queers often experience their marginalisation as a form of temporal displacement. Notable examples include a campy attraction to the outmoded; [...] an unusually long participation in ‘youth’ culture due to the importance of queer nightlife; the delayed or replayed puberty of trans folks; the melancholia of a prolonged attachment to lost loves, lost time, lost possibilities; the feeling of belonging to a world-to-come that accompanies queer utopianism, or, alternately, the feeling of having no future at all.’32

Viewing the journey in Freak Orlando as queer temporality allows Ottinger’s own journeys to be understood as displacement, albeit less in a negative sense than as a fork in the road of possibilities.

The filmmaker’s cut-and-mix-collage style here creates a time jump through different epochs. Accordingly, Ottinger referred to Freak Orlando as a small world theatre (“kleines Weltentheater”) which seems to zoom out and show the hustle and bustle of the vanity of the world. This metaphor serves a humorous, almost a light treatment of the suffering of the outcast throughout history of human existence. Does Freak Orlando point towards a queer utopia? A time-travelling machine for hopeful speculation? We see the freak, i.e. the future, threatened by social situations such as inquisition, fascism or normative psychiatry – “but the film’s resistance is the time it restores to us to read complex combinations of images beamed up from many different time zones and levels of meaning.”33

***

The incredible vastness and unpredictability of Ottinger’s imagery is what makes up its quality, so any attempt to describe her work can only seem reductive. And yet it seems worthwhile to observe closely the overlapping of the queer, the ethnographic, the fictional and the documentary bundled in the artist’s incessant travel interest. Ultimately, it is precisely the entanglement of these views that is the great artistic contribution of Ottinger’s life work. Paris Calligrammes offers not only autobiographical references to Ottinger’s socio-political upbringing, but also art-historical references of the figure of the artistic traveller through the fusion of expressions of queerness and the exoticisation of the cultural Other, by Surrealist and Dadaist predecessors.

The road movie Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia, Ottinger’s “documentary turn”, is an illuminating example of the seamless transition between the documentary and the fictional, but also of the seamless transition between the queer and the ethnographic gaze. It is a complex case study in the context of this accusation of political incorrectness. Through the feminist and queer reinterpretation of pedagogical eros, Ottinger critiques and transforms orientalist and patriarchal tropes, emphasizing mutual growth and experimental engagement with cultural rituals. Johanna d’Arc’s didactic staging of the encounter with the Other (or the failed encounter with the Other) stands exemplary of the filmmaker’s ultimate mastery: to create a constant self-reflexive image that offers us the experience of a view within a view, an artistic gesture that art historian Katharina Sykora has elsewhere described as “deictic”.34 Freak Orlando serves as a prime example of the great overview effect (which travelling can bring with it), which Ottinger knows how to stage skilfully. Always on the move, the film maker seems to observe the hustle and bustle of this world from a faraway vantage point. The film ultimately shows where travelling – time travel – deeply reflects queer life experiences, and how these topoi become resistance to reactionary, autocratic, soldierly, violent – and yes, colonial – world forces.

Paris Calligrammes presents Ottinger as a traveller who is also a flâneur. Her camera work, her montage, her pre-production, which introduces collecting as method and the scrapbook-cut-and-mix collage as a script, and above all the format of the station cinema of Paris Calligrammes and Freak Orlando, that reconcile the nomadic and the sedentary. It proves Ottinger as not just an explorer, but a transformative force. In Johanna d’Arc, the train becomes a metaphor for progress and displacement and evokes parallels to film history and psychoanalysis, where movement and observation overlap. Emblematic of Ottinger’s productions, which simultaneously observe through movement and move through observation.

Both Paris Calligrammes and Freak Orlando (and other films) formally exemplify a cinematic portrait of a city that is also a portrait of characters and vice versa. The places visited are never just a backdrop with specific reference points, but Ottinger allows them to become storytellers themselves. In this context her current film project deserves a special mention here as an outlook: Die Blutgräfin [The Bood Countess] – a vampire film and city portrait of Vienna and its elaborate Habsburgian death rituals. Haven’t we all been waiting for a lesbian vampire film? And is there any better city for the topic of death than Vienna?

This director still has a lot to tell and a lot to travel. Ottinger has seen the world and shown it to us, she has been to New York more than 60 times, spent several years in Asia and lived in different European countries – as so many German intellectuals who seem to be able to create truly only outside Germany? A highly relevant question...

- 1In Paris Calligrammes (2019), Ottinger explains these theoretical interests: “To know and understand one's own culture, one must learn to look at it from the point of view of another.”

- 2“Masterclass Mit Ulrike Ottinger,” Austrian Film Museum, 7 June 2022, video. Or Laurence A. Rickels, Ulrike Ottinger: The Autobiography of Art Cinema (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008).

- 3Rickels, Ulrike Ottinger: The Autobiography of Art Cinema.

- 4Enzo Traverso describes adeptly the socio-political impact of the Jewish intellectual community, termed Jewish modernity in the second half of the 20th century, between the Holocaust and the establishment of Israel in 1948, whose subversive power derived precisely from the experience as the pariah people, the exiles’ experience of always being the other of the established order. (Enzo Traverso, The End of Jewish Modernity (London: Pluto Press, 2016).)

- 5Such as in Die Betörung der Blauen Matrosen (1975), where Rosa von Praunheim and Frank Ripploh make out as a smooching sailor couple. (Angela Mc Robbie, Ulrike Ottinger - Film, Art and the Ethnographic Imagination (Intellect Ltd.: Bristol, 2024)

- 6Patricia White, “Ulrike Ottinger in the Mirror of her Movies,” in: Angela Mc Robbie, Ulrike Ottinger – Film, Art and the Ethnographic Imagination.

- 7Or as Patricia White formulated: “The view of the cultural other is the central challenge and concern across Ottinger’s oeuvre.” From Patricia White, “The Cosmos According to Ulrike Ottinger,” The Criterion Collection, 26 July 2022.

- 8Ulrike Ottinger, “Director’s Statement,” 2020.

- 9“Interview with Ulrike Ottinger on ‘Paris Calligrammes’,” Teddy Award, 22 February 2020, video

- 10Almost all the artistic role models Ulrike mentions are male.

- 11Ulrike Ottinger, “Director’s Statement”.

- 12“Ulrike Ottinger at 80: In Conversation,” GoetheUK, 26 October 2022, video.

- 13Ulrike Ottinger, “Stations of Cinema: A Short Tale on Storytelling in Free Images,” in: Kunst-Werke (ed.), (Bildarchive: Berlin, 2001).

- 14Thomas Love, “Anachronism and Anti-Conquest: On Chamisso’s Shadow,” in Angela Mc Robbie (ed.), Ulrike Ottinger - Film, Art and the Ethnographic Imagination.

- 15Ulrike Ottinger, “Director’s Statement”.

- 16Dominic Paterson, “‘Paris-Berlin et le monde entier’: Ulrike Ottinger’s Points of Departure,” in Angela Mc Robbie (ed.), Ulrike Ottinger – Film, Art and the Ethnographic Imagination. As in Walter Benjamin’s poetic texts, Ottinger’s films reveal a pronounced penchant for allegory and medieval forms of representation.

- 17Gerald A. Matt and Verena Konrad, “Grotesque Moments. Ulrike Ottinger in Conversation with Gerald A. Matt and Verena Konrad,” Sabzian, 27 November 2024.

- 18As argued by cultural researcher Dominic Paterson in “‘Paris-Berlin et le monde entier’: Ulrike Ottinger’s Points of Departure”.

- 19In 2005, Katharina Sykora titled this collecting frenzy similar to “hoarding,” describing the sheer abundance. (Katharina Sykora, “A Photographic Hoard” in: Ursula Blickle, Catherine David & Gerald Matt (eds), Ulrike Ottinger: Image Archive (Nürnburg: Verlag für modern Kunst Nürnberg, 2005). Furthermore, Ulrike Ottinger boasts a remarkable practice of exhibition-making, which in itself is a practice of reorganisation and association, of knowledge production.

- 20Discussion with the artist in preparation of the Brussels retrospective, 20 June 2024, Berlin.

- 21Patricia White, “The Cosmos According to Ulrike Ottinger”.

- 22Mc Robbie, Ulrike Ottinger – Film, Art and the Ethnographic Imagination.

- 23A reference to Oscar Wilde’s feminist figure who escapes an unhappy Victorian aristocratic marriage and family constellation.

- 24For example, through show amusements such as the Trans-Siberian Railway Panorama, a one-hour journey in a stationary carriage from Moscow to Beijing at a World Expo in Paris. (If you follow the significance of the train in film history, you will of course pass the Lumiére brothers.) (Laurence A. Rickels, Ulrike Ottinger: The Autobiography of Art Cinema)

- 25Ibid.

- 26Patricia Wiedenhöft, “Interview with Ulrike Ottinger,” website Ulrike Ottinger.

- 27Cassandra Xin Guan, “Rewriting the Ethnos through the Everyday: Ulrike Ottinger’s China. Die Künste – Der Alltag” in: Mc Robbie, Ulrike Ottinger – Film, Art and the Ethnographic Imagination.

- 28Patricia Wiedenhöft, “Interview with Ulrike Ottinger”.

- 29Erica Carter and Hyojin Yoon, “A Timely Education: Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia (1989)” in: Mc Robbie, Ulrike Ottinger – Film, Art and the Ethnographic Imagination.

- 30Also fitting is the recurring jingle of the Yiddish song “Bey mir bist scheyn,” which frames the narrative with a beginning and concluding performance. Written in 1938 by the Andrews Sisters for a musical, the lyrics are difficult to translate and may oscillate in meanings between: “When you are here with me you are beautiful” or “in my view you are beautiful” which may therefore refer to a spatial relation, and therefore echoes the Eros between the traveller and the foreign culture, in a different way.

- 31An experimental actress and scenographer who worked extensively with von Praunheim, Schroeter and Fassbinder, etc.

- 32Thomas Love, “Temporal Displacement in Ulrike Ottinger’s Films,” The Germanic Review (2022). Accessed December 1, 2024.

- 33Ibid.

- 34Katharina Sykora, “On Showing: Ulrike Ottinger’s Deictic Gestures”. Lecture at UCLA Humanities Department (2020).

This essay accompanies the Ulrike Ottinger retrospective – Theatrum Mundi –, held by Goethe-Institut Brussels and CINEMATEK in collaboration with Sabzian. From December 6th, 2024 until February 2025, the complete film retrospective will be shown with an accompanying exhibition that zooms in on selected film projects and processes of the artist. Here a select few of Ottinger’s “work books” are at display in the CINEMATEK, allowing a wonderful insight in the creation of her cinematic oeuvre.