“Some filmmakers say “this is my work and I want it to stay that way”. That is their right, and we respect that right. Those are the films we don’t buy, and those are the films we don’t transmit.”

TV executive in The Universal Clock: The Resistance of Peter Watkins (Geoff Bowie, 2001)

“Watkins does not reconstruct la Commune except to speak of our submission to the ‘permanent mercantilism’ of the televisual media; of our defused anger. And after three and a half hours, in a meeting in the local quarter, the actresses throw away their masks, suddenly evoking the combat of the ‘sans-papiers’ [immigrants without resident papers who risk being ejected from France], the condition of women put to sleep by comfort ... The film becomes a furious ode to direct democracy: Watkins makes sure that the actors take power in the film, as did their personages in Paris. They denounce the media as organs of Versailles. Screen title: ‘What the media is afraid of is to see the little man in the small screen replaced by a multitude of people - the public’. Alas, Watkins, too late! The public, the ‘people’, we see only this, today. Everywhere and at all times ... assimilated by our all-digesting gaze. All the same, a Communard actress finishes before she dies, by crying out directly [to the TV Communale filming her], ‘Whether this is film or reality, all you do is watch us, but you don’t give a damn! It’s this that I want to kill!’ It’s 3:30 AM, and we, the last of the television viewers, are roused by this cry; at this instant, the Versaillais, they are us.”

Philippe Lançon

“The Monoform is like a time-and-space grid clamped down over all the various elements of any film or TV programme. This tightly constructed grid promotes a rapid flow of changing images or scenes, constant camera movement, and dense layers of sound. A principal characteristic of the Monoform is its rapid, agitated editing, which can be identified by timing the interval between edited shots (or cuts), and dividing the number of seconds into the overall lengthof the film. In the 1970s, the Average Shot Length for a cinema film (or documentary, or TV news broadcast) was approximately 6-7 seconds, today the commercial ALS is probably circa 3-4 seconds, and decreasing.

It is my belief that the excessive demands of these flashing images on our emotional and intellectual responses can lead to blurred distinctions between themes, and to a confusion in selecting and prioritizing our reactions (e.g., to the news scene of a bleeding body in a bombed area in Syria, which is followed by a commercial message, and sooner of later, by the image of a similarly bleeding body in a film or TV drama, etc.).

Despite academic claims that audiences have become ‘media literate', the standardized rate at which audiovisual information is delivered is probably far too swift to be properly managed by the brain, which has to digest and process the rapid and continual change of visual (and audio) information from one scene to the next, and to the next, and to the next, and so on. I can anticipate a negative response from the media education sector to this analysis on the grounds that it is ‘arrogant' to presume that audiences cannot understand or decipher the workings of the Monoform (even if they believe such a thing exists). But the fact that viewers ingest the Monoform every day is not a precursor to understanding how (or why) it functions in the way that it does. The form itself may neutralize any understanding of how it works, including by habituating us to its presentation, not to mention its more subterranean and less perceivable properties. As this subject is never raised by the MAVM [Mass Audio-Visual Media], and is too rarely discussed by media educators, there is hardly a wealth of analysis or information for people to rely on.”

Peter WatkinsPeter Watkins, “Dark Side of the Moon,” http://pwatkins.mnsi.net/dsom.htm[/fn]

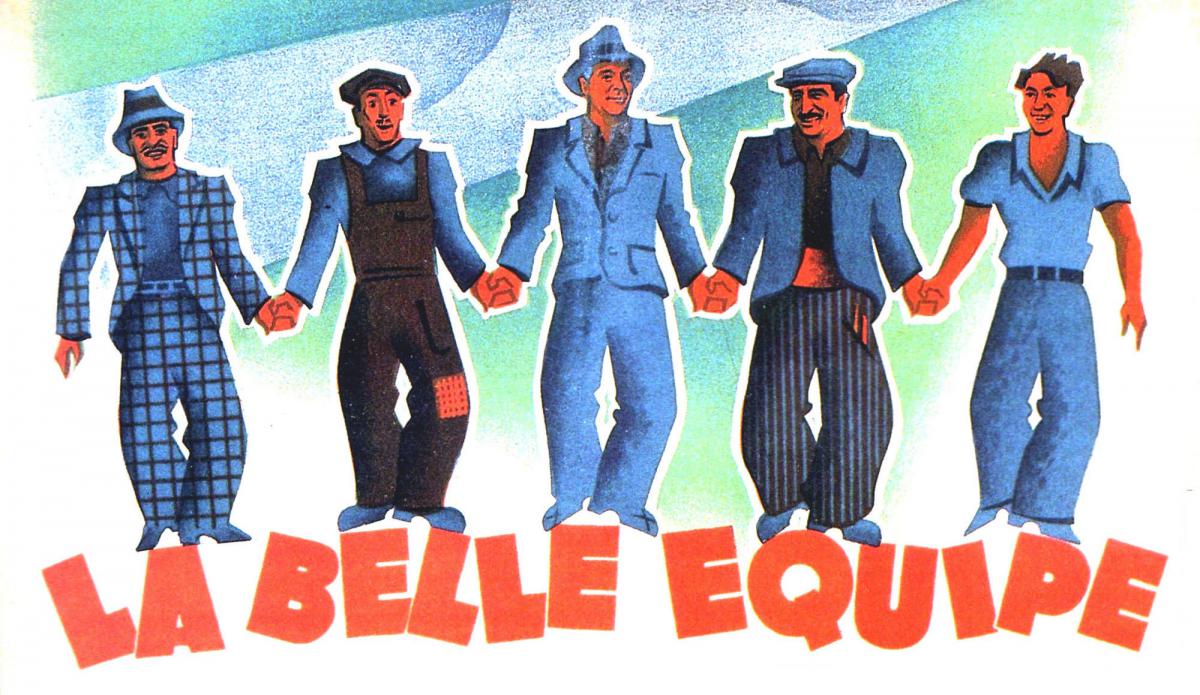

“Why this film, at this time?

We are now moving through a very bleak period in human history - where the conjunction of Post Modernist cynicism (eliminating humanistic and critical thinking in the education system), sheer greed engendered by the consumer society sweeping many people under its wing, human, economic and environmental catastrophe in the form of globalization, massively increased suffering and exploitation of the people of the so-called Third World, as well as the mind-numbing conformity and standardization caused by the systematic audiovisualization of the planet have synergistically created a world where ethics, morality, human collectivity, and commitment (except to opportunism) are considered “old fashioned.” Where excess and economic exploitation have become the norm - to be taught even to children. In such a world as this, what happened in Paris in the spring of 1871 represented (and still represents) the idea of commitment to a struggle for a better world, and of the need for some form of collective social Utopia - which WE now need as desperately as dying people need plasma. The notion of a film showing this commitment was thus born.

Centralizing? Collective? - or both?

I realize that a large cast, and the necessity for many people (who in more traditional films would be relegated to the background as silent ‘extras’) to speak, did frequently limit the length of time in which they could express themselves as individuals. But I believe that this was balanced by scenes where space was given to individual expression, and by the sheer length of the final film. Since an overall objective of ‘La Commune’ was to present a collective voice, I believe that the filming achieved this in a way which is highly unusual in the MAVM today.

Centralizing? Collective? - or both? Another reason for such emphasis on long sequences, including during the editing, was because the fragmentation caused by the camera arriving and departing was not the only ensuing process - a study of these sequences shows that Gérard and Aurèlia often approach a group, ask a question, and then retreat while a discussion develops between the members of the group, who speak over and across the TV interviewers; the technology is thus used only to facilitate people communicating with each other. I find these moments very exciting - they were often very spontaneous, and exemplify how ‘La Commune’, while ostensibly implementing a Monoform technique, departs radically from it.

‘The Universal Clock’, and the length of La Commune

La Commune was originally planned as a two hour production. But the method of filming long sequences expanded the internal construction of the film to the point where it became impossible to reduce it beyond a certain stage during the editing, without destroying the very process which had developed in the filming. In the end, La Commune emerged as a film of five hours 45 minutes. For me, this was a very difficult decision on certain levels; reaction to my other later films (The Journey and The Freethinker) has shown that herein lies the road to complete marginalization - partly by film critics, and totally by today’s MAVM. I was very conscious of this as I began to make decisions regarding the length of ‘La Commune’. I have written about the problems of FORM and PROCESS, and the ways in which La Commune has tried to address these issues. Now we come to the question of LENGTH in the MAVM - the way that time is used (or abused). The existing tendency - ruthlessly enforced by TV executives, especially Commissioning Editors - is to increasingly reduce and fragment the format and space available to filmmakers and the audience. At the present time, filmmakers producing TV dramas or documentaries are usually permitted a maximum of 52 minutes - in order to allow commercials to fill up the remainder of the hour. There are indications that this may be dropping to 47 minutes, and in some countries, e.g. Canada, a maximum of 22 minutes is increasingly being applied to documentaries. I have heard executives within the MAVM state that these time-spans are the result of what they refer to as ‘the universal clock’. This being the case, we can now see how the MAVM use the Monoform as a metronome governing the rhythm and internal structure of their global audiovisual ‘clock’.”

Peter WatkinsPeter Watkins, “La Commune (de Paris, 1871)”, http://pwatkins.mnsi.net/commune.htm[/fn]